Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Diabetes and CVD Risk in African Americans

Uploaded by

Indah RismandasariOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Diabetes and CVD Risk in African Americans

Uploaded by

Indah RismandasariCopyright:

Available Formats

Am J Cardiovasc Dis 2016;6(3):129-137

www.AJCD.us /ISSN:2160-200X/AJCD0032089

Original Article

Diabetic indicators are the strongest predictors for

cardiovascular disease risk in African American adults

Ashley N Carter1, Penny A Ralston2, Iris Young-Clark2, Jasminka Z Ilich1,3

1

Department of Nutrition, Food and Exercise Sciences, Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida, USA; 2Center

on Better Health and Life for Underserved Populations, Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida, USA; 3Insti-

tute for Successful Longevity Affiliate, Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida, USA

Received May 12, 2016; Accepted August 21, 2016; Epub September 15, 2016; Published September 30, 2016

Abstract: African Americans have higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD) com-

pared to other racial groups. Modifiable and non-modifiable factors play a role in the development of both diseas-

es. This study assessed diabetes indicators in relation to other CVD risk factors taking into account confounders,

among African American adults. This was a cross-sectional study in mid-life and older African Americans (45

years) who were recruited from the local churches. Fasting blood was collected and serum analyzed for diabe-

tes indicators, apolipoproteins, adipokines, and lipid profile. CVD risk scores were determined using the American

Heart Association and Framingham Risk Score assessments. Homeostasis Model Assessments (HOMAs) were cal-

culated using glucose and insulin concentrations. Confounding variables were assessed by questionnaires. Data

were analyzed using SPSS software, version 21, and p<0.05 was deemed significant. Descriptive statistics was

used to analyze continuous variables. Frequencies and percentages were used to examine categorical variables.

T-tests compared different groups while Pearson correlations provided preliminary relationships and determined

variables for multiple regression analyses. A total of n=79 participants were evaluated (69% women), 59.39.2

years, BMI=34.78.3 (meanSD). As expected, AA men had higher fasting blood glucose than women (123.654.9

mg/dL versus 99.021.8 mg/dL), and AA women had higher insulin (11.813.1 mg/dL versus 7.66.0 mg/dL).

Our study confirmed that it is likely for AA men to have significantly lower adiponectin concentrations in compari-

son to AA women. Based on the CVD risk assessments, men had a significantly higher risk of developing CVD than

women, which has been shown previously. Apolipoproteins, adipokines, and lipid profile also negatively influenced

the cardiovascular health outcomes in men. Dietary intake, probably by influencing participants weight/adiposity,

contributed to the differences in cardiovascular outcomes between men and women. In conclusion, the findings of

this study revealed that diabetes and serum glucose appeared to be the leading factors for high CVD risk, on the

contrary to some other indicators reported in some studies, e.g. hypertension or dyslipidemia.

Keywords: African Americans, aging, blood glucose, cardiovascular disease risk, type 2 diabetes, diet

Introduction duals with T2DM have additional cardiovascu-

lar disease (CVD) risk factors such as hyperten-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a prevalent sion and dyslipidemia [1, 2].

chronic disease in the United States, affecting

approximately 29 million Americans, with the Previous research showed that T2DM indicator

disproportionately higher distribution among serum hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) concentration

African American (AA) adults [http://www.cdc. is positively associated with low density lipopro-

gov]. Approximately 9.3% AA adults and 5.9% tein (LDL) concentration and systolic blood

Caucasian American (CA) adults have T2DM pressure [3], while higher fasting insulin con-

[http://www.cdc.gov]. The two groups also dif- centration is a strong indicator of diabetes in

fer regarding the prevalence of obesity, with women [4]. It has been shown that AA men have

about 48% of AA and 33% of CA adults being higher fasting blood glucose than CA men [5].

classified as obese [http://www.cdc.gov]. It is Additionally, in comparison with CA women, AA

well established that adiposity plays a major women have a higher prevalence of insulin

role in the development of T2DM and other resistance according to the homeostasis model

chronic diseases [http://www.cdc.gov]. Indivi- assessment (HOMA) -- a calculation using

Diabetes and cardiovascular health among African Americans

serum insulin and glucose to determine the recruited from six churches in North Florida

degree of the bodys response to insulin and participating in a church-based longitudinal

functioning of pancreatic beta cells [5]. intervention to reduce CVD risk, as described

previously [16]. For this study, only baseline

It is well established that both age and gender data were used. The protocol was approved by

play a role in CVD risk factors [4-6]. Past the Institutional Review Board.

research also showed that the prevalence of

T2DM differed based on education and income, Anthropometric and blood pressure measure-

suggesting that the social determinants to ments

health outcomes are important [7]. Socioeco-

nomic status may be associated with diet and Weight was measured in pounds with the Tanita

physical health [6], and in particular, education- digital scale (Arlington Heights, IL) and convert-

al level may predict cardiovascular health [8]. ed to kg. Using a Charder Stadiometer (Iss-

Dietary intake, including energy and fat con- aquah, WA), height was measured in centime-

sumption, as well as physical activity are well ters (cm). For such measurements, the partici-

known modifiable health-risk factors. Having a pants wore light clothing and no shoes. The

long-term high energy and fat intake and sed- abdomen, hip, and waist were measured in cm

entary lifestyle may increase the chance of with a plastic non-flexible measuring tape (Is-

uncontrolled blood glucose, lead to weight gain, saquah, WA). The abdomen was measured at

and eventually increase the incidence of both the top of the iliac crest, the hip at the largest

T2DM and CVD [9, 10]. In addition to the above circumference around the buttocks, and waist

indicators, other confounding factors like mari- at the narrowest part of the torso, while each

tal status, current and/or past smoking, per- participant was exhaling. Blood pressure was

ceived health status, and medication use may measured on the non-dominant arm after each

play an important role in CVD health outcomes participant rested for a few minutes, using a

[7, 8, 11-13]. digital device (A&D Medical, Miltitas, CA).

It is well established that AA adults have been Cardiovascular risk assessments

typically excluded from clinical trials or other

research projects, because they were charac- The risk for CVD was determined using the

terized as being a high risk group for adverse Framingham CVD risk score assessments and

cardiovascular health [14]. The eligibility crite- the American Heart Association Guidelines

ria for research needs to be expanded to inc- [http://www.framinghamheartstudy.org, http://

rease the potential for exploring multiple con- my.americanheart.org]. As determined by the

founding factors, but particularly race, in CVD Framingham Heart Study and the American

health in this population. For such reasons, fur- Heart Association, such risk scores take into

ther research is needed in the AA adult popula- account blood pressure, use of blood pressure

tion to provide more clarification for specific medications, perceived health for diabetes,

T2DM outcomes and CVD risk factors [15]. The smoking status, age, and gender [http://www.

aim of this study was to assess T2DM indica- framinghamheartstudy.org, http://my.america-

tors in relation to selected CVD risk factors nheart.org]. The American Heart Association

(blood pressure and lipid profile), accounting Guidelines also take into account race, choles-

for the confounding factors in mid-life and older terol, and HDL [http://my.americanheart.org].

AA adults who were recruited from a church- In addition, the Framingham risk scores include

based health intervention study. We hypothe- either BMI or cholesterol and HDL [http://www.

sized that several factors will be associated framinghamheartstudy.org].

with higher CVD risk in this cohort, but particu-

The Framingham risk scores range from 0-30,

larly high glucose levels.

whereas the American Heart Association risk

Methods scores range from 0-100 [http://www.framing-

hamheartstudy.org, http://my.americanheart.

Participants org]. In regards to the Framingham risk score,

each factor is associated with a score to calcu-

The participants included n=79 mid-life and late the chance of adverse health within a

older (45 years old) AA men and women, 10-year period [http://www.framinghamheart-

130 Am J Cardiovasc Dis 2016;6(3):129-137

Diabetes and cardiovascular health among African Americans

study.org]. For example, a total number of 9 Clinical parameters

points is associated with a <1% chance of a

10-year risk for women and 5% chance for men; Overnight fasting blood samples were collected

20 points is associated with 11% chance of at data collection sessions. The red blood cells

coronary heart disease in 10 years for women were separated by centrifugation and serum

and 30% chance for men [http://www.framing- was stored at -80C until further analyses. The

hamheartstudy.org]. routine tests like glucose, insulin, and lipid pro-

file were analyzed by a contracting laboratory

T2DM indicators (Clinical Laboratory, Tallahassee Memorial Ho-

spital, FL). Apo A1, Apo B, and adiponectin were

Fasting serum glucose and insulin were used to analyzed in our laboratory, by commercially

calculate HOMA-IR (insulin resistance) and available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

HOMA- (beta-cell functioning) [5, 17, 18], and (ELISA) kits (Parameter, R&D Systems).

they were used as T2DM indicators. Fasting

serum glucose >126 mg/dL is associated with Data analysis

T2DM [17], while fasting serum insulin of >21

/mL is characterized as insulin resistance Using IBM SPSS, version 21 (Armonk, NY), the

[19]. data were analyzed by calculating descriptive

statistics, t-tests, Pearson correlations, and

Confounding factors regression analyses. The descriptive statistics

(means and the standard deviation) included

Underlying factors such as gender, education the continuous values for most of the variables,

level, marital status, current smoking status, while frequencies and percentages were used

perceived health status, and medication intake to analyze the categorical variables (gender,

were collected using a self-administered ques- education level, marital status, current smok-

tionnaire at data collection sessions at the ing status, perceived health status, medication

churches. Education level was based on the use, and physical activity). The Pearsons cor-

following codes: 1=some high school, 2=high relations of specific factors were used to iden-

school graduate, 3=some college, 4=Bachel- tify the variables for the multiple regression

ors Degree, and 5=Post-baccalaureate. In ad- analyses. The significant differences between

dition, marital status was coded 1=single, 2= men and women were determined using two

married, 3=divorced/separated, and 4=widow- sample t-tests, taking into account the Levenes

ed. Current smoking status was coded as 1= test to assess the equality of variances. T-tests

smoker and 2=non-smoker. Perceived health were also used to compare participants who

was based on participants indicating they had took medication (for diabetes, hypertension,

the following health problems: T2DM, hyperten- and/or dyslipidemia) with those who did not

sion, and dyslipidemia. Medication intake was take such medications. A p-value less than

determined from those who had a perceived 0.05 was deemed significant.

health problem (T2DM, hypertension, dyslipid-

emia). Participants who were taking medica- Results

tions were coded as 1 and those who did not as

0. Of 79 participants, 69% were women. Sample

size varied for some variables due to missing

Dietary and physical activity assessments data and is noted in tables. Most of the partici-

pants were married (51.9%) and had a college

The 24-hour dietary recalls were collected and level education (59.5%). Men were more likely

analyzed for energy and fat consumption using to smoke and use T2DM medication than

Food Processor (Esha, Salem, Oregon). Physical women. Over half of the participants (58%)

activity was coded as 1=0 minutes, 2=15 min- were taking medication(s) for at least one of the

utes, 3=30 minutes, 4=45 minutes, and 5=60 following: diabetes, blood pressure, and dyslip-

minutes per day. The types of physical activity idemia. Among the participants taking medica-

included gardening, household chores, run- tions, more men tended to have diabetes than

ning/walking, and other types of habitual activi- women. Not surprisingly, the frequency and

ties, as described previously [16]. number of medications in the older participants

131 Am J Cardiovasc Dis 2016;6(3):129-137

Diabetes and cardiovascular health among African Americans

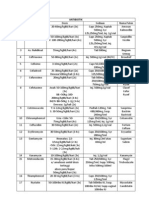

Table 1. Anthropometrics and blood pressure of participants (MeanSD)

No medicationsa Medications

Variables Men (n=23) Women (n=51) Total (n=79)c

(n=33) (n=46)

Age (years) 55.47.4* 62.19.5* 59.39.3 59.69.6 59.39.2

Height (cm) 167.99.8 165.310.7 174.011.4* 163.1 8.1* 166.410.4

Weight (kg) 92.827.5 99.627.9 108.832.4* 92.324.3* 96.827.8

BMI (kg/m2) 32.78.2 36.38.2 35.79.0 34.5 8.0 34.78.3

Abdomen circumference (cm) 105.215.0 116.017.4 112.616.8 111.6 17.4 111.517.2

Hip circumference (cm) 115.314.8 121.515.9 115.414.7 120.4 15.7 118.915.7

Waist circumference (cm) 101.618.2 108.817.6 110.617.9 103.9 16.9 105.818.1

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg)b 130.420.2 133.917.6 133.914.3 131.8 20.1 132.518.7

Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg)b 83.213.1 79.710.8 80.212.8 81.7 11.6 81.211.9

SD, standard deviation; cm, centimeter; kg, kilogram; m, meter; BMI, body mass index; mmHg, millimeter of mercury. a42% of

the total sample was not taking medications. b53% of the participants were taking blood pressure medications. cSample size

ranged from n=74 to n=79 because of missing data. *Statistically significant as compared between men and women and/or

between those with and without medications.

Table 2. Energy and fat consumption and physical activity (MeanSD)

No medicationsa Medications

Variables Men (n=23) Women (n=51) Total (n=74)

(n=31) (n=46)

Energy Intake (kcal/day) 1584.8549.4 1552.1461.9 1918.9587.5* 1409.8366.8* 1565.2495.7

Fat Intake (% of kcal/day) 32.38.9* 37.18.8* 36.28.6 34.99.1 35.29.1

Fat Intake (g/day) 57.023.1 64.928.9 76.626.6* 55.724.9* 61.726.8

Physical Activityb (min/day) Number (%)

0 minutes 4 (12.1) 6 (13.0) 2 (8.7) 8 (15.7) 10 (12.7)

15 minutes 8 (24.2) 11 (23.9) 3(13.0) 15 (29.4) 19 (24.1)

30 minutes 5 (15.2) 9 (19.6) 5 (21.7) 9 (17.6) 14 (17.7)

45 minutes 12 (36.4) 18 (39.1) 11 (47.8) 19 (37.3) 30 (38.0)

60 minutes 0 (0) 1 (2.2) 1 (4.3) 0 (0) 1 (1.3)

SD, standard deviation; kcal, kilocalorie; g, gram; min, minutes. a42% of the total cohort was not taking medications. bPhysical

activity includes any movement such as gardening, household chores, running. *Statistically significant as compared between

men and women and/or between those with and without medications.

were higher compared to younger ones in the significantly (p<0.05) higher energy and fat

cohort. intake in comparison to women. Differences in

energy and fat intake were also noted among

Age, anthropometrics, and blood pressure of the participants who took medication(s); they

the participants are presented in Table 1. As consumed a significantly higher percentage of

expected, the weight and height were higher in energy from fat. Among all of the participants, a

men than in women, but the BMI was insignifi- lower percentage of men were sedentary in

cantly (p>0.05) different between them, possi- comparison to women.

bly due to a small effect size of 0.14. Weight

and height each had a large effect size, increas- Furthermore, men had significantly (p<0.05)

ing the chance to detect a significant difference higher fasting serum glucose, and women had

between men and women. The participants higher insulin, which is typical in the AA popula-

who were taking medications were significantly tion (Table 3). Scores for HOMA-IR, and HOMA-

older and tended to be heavier, but no other were also higher among women (Table 3). Am-

statistical significance was noted compared to ong people who took medication(s), women had

those not taking medications. significantly higher HOMA- scores than men.

On average, men tended to have higher systolic

Energy and fat intake also differed based on blood pressure, triglycerides, LDL, VLDL, cho-

gender, as depicted in Table 2, with men having lesterol/HDL ratio, and Apo B concentrations.

132 Am J Cardiovasc Dis 2016;6(3):129-137

Diabetes and cardiovascular health among African Americans

Table 3. Clinical parameters (MeanSD)

Variables No medicationsa Medicationsb Menc Womend Totale Normal

Glucose (mg/dL)f 104.044.7 107.928.6 123.654.9 99.021.8 106.236.1 110

Insulin (microU/mL)f 12.614.9 8.57.5 7.66.0 11.813.1 10.311.4 <21

HOMA-IR 2.92.8 2.32.5 2.32.1 2.82.9 2.62.6 <2.68

HOMA- 56.8335.2 83.770.4 64.050.9 77.5279.4 72.0225.6 >40%

Triglycerides (mg/dL) 91.643.8 76.758.6 87.346.0 83.957.9 83.053.1 <150

Cholesterol (mg/dL)g 192.935.1 182.637.2 183.736.0 189.437.7 186.936.5 <200

HDL (mg/dL) 47.615.3 51.715.1 39.910.9* 53.714.5* 50.015.2 40-60

LDL (mg/dL) 126.929.0 114.228.8 126.432.7 117.828.7 119.629.4 <130

VLDL (mg/dL) 18.38.8 13.84.9 17.59.2 15.46.1 15.77.2 5-40

Cholesterol/HDL 4.31.3 3.81.2 4.91.5 3.71.0 4.01.3 <5

Adiponectin (g/mL) 6.03.7 5.62.7 4.52.7* 6.13.0* 5.83.1 3-14

Apo A1 (mg/mL) 6.13.9 5.43.2 4.43.0 5.93.5 5.73.5 >1.2

Apo B (mg/mL) 1.70.9 1.40.9 1.80.9 1.50.9 1.50.9 <0.8

mg/dL, milogram/deciliter; microU/mL, microunits/milliliter; HOMA-IR, Homeostasis Model Assessment-Insulin Resistance;

HOMA-, Homeostasis Model Assessment-Beta Cell Functioning; HDL, High Density Lipoprotein; LDL, Low Density Lipoprotein;

VLDL, Very Low Density Lipoprotein; g/mL, microgram/milliliter; Apo A1, Apolipoprotein A1; Apo B, Apolipoprotein B. a42% of

the total sample was not taking medications. Sample size ranged from n=32 to n=33 because of missing data. bSample size

ranged from n=42 to n=46 because of missing data. cThe number of men ranged from n=19 to n=23 because of missing data.

d

The number of women ranged from n=49 to n=51 because of missing data. eSample size ranged from n=74 to n=79 because

of missing data. f21% of the participants were taking medication for diabetes. g35% of the participants were taking medication

for cholesterol. *Statistically significant as compared between men and women.

Table 4. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) assessments (MeanSD)

No medications Medications

Assessment Men (n=23) Women (n=51) Total (n=74)

(n=28) (n=46)

Framinghama 12.78.9c 22.37.5c 24.86.2 15.99.1 18.79.3

Framinghamb 11.08.3c 16.78.3c 21.37.6c 11.57.4c 14.58.7

American Heart Association 7.25.7 15.811.2 17.612.6c 10.38.3c 12.510.4

a

Body Mass Index (BMI) is used to calculate the risk score for CVD. bThe lipid profile is used to calculate the risk score for CVD.

c

Statistically significant as compared between men and women and/or between those with and without medications.

In comparison, women had higher diastolic population of participants taking medication(s),

blood pressure, total cholesterol, HDL, adipo- each CVD risk assessment was significantly

nectin, and Apo A1. Men had significantly (p<0.05) higher for men in comparison to wo-

(p<0.05) lower HDL concentrations in the total men. A similar trend of significant CVD risk

population. A similar trend of significantly (p< scores was also observed for participants not

0.05) lower HDL concentrations was observed taking medication(s).

with men not taking medication(s).

Pearson Product Moment analysis revealed sig-

The CVD risk assessed either by Framingham nificant correlations among the clinical param-

or American Heart Association assessment eters. Insulin and HOMA-IR were significantly

yielded higher 10-year CVD risk scores for men and negatively correlated with adiponectin in

compared to women (Table 4). The aforemen- the total sample (r=-0.389; p<0.05). In addi-

tioned phenomenon of CVD risk between men tion, HOMA- was significantly positively corre-

and women also occurred among participants lated with cholesterol (r=0.369; p<0.05) and

who took medication(s) and those who did not. LDL (r=0.359; p<0.05). Similar trends were

The AHA risk score and Framingham Assess- observed with participants not taking medi-

ment that included the lipid profile were signifi- cation(s). Furthermore, glucose was significant-

cantly (p<0.05) different between men and ly correlated with cholesterol (r=0.375; p<0.05)

women in the total population. However, in the and LDL (r=0.431; p<0.05) among the partici-

133 Am J Cardiovasc Dis 2016;6(3):129-137

Diabetes and cardiovascular health among African Americans

Table 5. Multiple regression models with CVD risk score and diabetes indicators as dependent vari-

ables

Dependent variables Explanatory variables p Model R(adj)2

Model 1a

HOMA- Cholesterol 0.32 <0.01 0.26

Insulin -0.38 <0.001

Model 2a,b

Framingham CVD assessment Glucose 0.08 <0.01 0.29

Age 0.42 <0.001

Model 3a,c

Insulin Adiponectin -1.5 <0.001 0.21

Physical activity -2.7 <0.01

Model 4d

Glucose Waist circumference 0.53 0.02 0.21

HOMA- -0.17 <0.01

CVD, cardiovascular disease; adj, adjusted; HOMA-, Homeostasis Model Assessment-Beta Cell Functioning. aThe multiple

regression model was for the total cohort. bThe lipid profile was used to calculate the risk score for CVD. cA similar multiple

regression model occurred in for the participants not taking medications. dThe multiple regression model was for participants

taking medications.

pants not taking medication(s). Multiple regres- Men had a larger waist circumference than

sion models (Table 5) with CVD risk score and women (110.617.9 cm vs 103.916.9 cm),

diabetes indicators as dependent variables although not statistically significant, and the

show multiple factors influencing the cardiovas- average waist circumference and BMI in men

cular health of the total cohort. were associated with CVD risk factors from the

Framingham and American Heart Association

Discussion assessments. Men also had lower adiponectin

The overall purpose of this study was to assess concentrations than women, possibly due to

T2DM indicators in relation to selected CVD greater adiposity, as shown in a previous study,

risk factors (blood pressure and lipid profile) where adiponectin was lower in AA adults with

and confounding factors in mid-life and older T2DM than in those who were not diabetic [18].

AA adults, in a church-based health interven- Dietary choices (higher energy and fat con-

tion study, utilizing only baseline data. Unlike sumption) were influencing the cardiovascular

some of the past research [14], our study outcomes in this population. As reviewed rec-

included the participants taking medications ently [20], inflammation and oxidative stress,

and those with T2DM to account for a wider caused by an unhealthy and pro-inflammatory

health range of mid-life and older AA adults. diet are associated with multiple chronic dis-

Previous research about the enrollment of AA eases.

adults reported that AA adults were often

excluded from research due to multiple morbid Of the T2DM indicators (insulin and glucose),

conditions, including T2DM [14], leading to gap men had higher fasting serum glucose but

in research in that population, which this study women had higher insulin concentrations,

is trying to reduce. which was consistent with some previous

research [4, 7] where women had higher insulin

In brief, we showed that a higher percentage of concentration and increased CVD risk [4].

men used T2DM medication than women Therefore, the type of diabetes indicator has

(30.4% versus 19.6%), indicating that the T2DM played a role in the conclusions about the sus-

was more prevalent in men than in women, as ceptibility to CVD. Past research about dietary

has been also corroborated in other studies [7]. intake in community-based participatory study

However, observing similar trends among peo- also reported higher glucose in men [11] and

ple were taking medications and those who higher HOMA-IR in women. Similar results were

were not, adds to the novelty of this study. also supported by the findings of previous

134 Am J Cardiovasc Dis 2016;6(3):129-137

Diabetes and cardiovascular health among African Americans

research [5], where the CVD risk factors in AA cose may have caused men to have higher rate

adults were investigated and showed higher of comorbidities than women (65.2% versus

glucose among men. Hence, T2DM indicators 47.1%).

assessed in our study were able to detect

adverse health based on gender, which is cor- Consistent with a past study [11], AA men in our

roborated in previous research that examined study consumed diets higher in energy and fat,

CVD risk factors [4]. which might have also contributed to the worse

CVD outcomes. With regard to other confound-

Bertoni et al., investigated the proportion of ers, women have been more likely to have high-

overweight and obese adults having met the er education and be non-smokers in our study,

American Diabetes Association criteria for as well as in others [11]. T2DM duration and

T2DM, including hypertension and dyslipidemia family history are other fundamental factors for

and found that AA adults were less likely to future research, which were not evaluated in

have control of the CVD risk factors in compari- our study. Being able to add to current scientific

son to CA adults [7]. In addition, lower adipo- knowledge and detect CVD risks through multi-

nectin concentrations found in our study were ple measures can be incorporated into clinical

associated with T2DM, consistent with the practice as a more comprehensive approach

study of glucose tolerance in AA adults where that can be specific for men and women who

adiponectin was significantly lower among par- identify as AA.

ticipants with the disease [18]. The high choles-

terol/HDL ratio, indicating higher CVD risk, is Our study has some limitations. We used the

comparable to the study in middle and older American Heart Association CVD Assessment

age AA women that linked body fat or blood lip- and the Framingham Risk Assessments to

ids with CVD risk factors [21]. determine the susceptibility to and/or predict-

ability for CVD [http://www.framinghamheart-

We also assessed other CVD risk factors study.org, http://my.americanheart.org]. The

(hypertension [systolic and diastolic blood pres- Framingham Risk Scores tended to be higher

sure] and dyslipidemia [triglycerides, choles- than the American Heart Association Guidelines

terol, HDL, LDL, VLDL, cholesterol/HDL, Apo Scores. Such findings could have been influ-

A1, Apo B, and adiponectin]) in our cohort. enced by race. Unlike the Framingham Risk

Similar to past research that investigated CVD Scores, the American Heart Association con-

risk factors [5], AA men had a higher systolic siders race in determining the CVD risk [http://

blood pressure, and AA women had a higher www.framinghamheartstudy.org, http://my.am-

diastolic blood pressure. Men in our study had ericanheart.org]. The assessments collectively

higher serum triglycerides concentrations com- indicated that men had a higher 10-year risk for

pared to women, which was also corroborated adverse cardiovascular health and the main

in other studies [5, 22]. Among cohorts of determining factors included smoking, higher

Caucasians and African Americans, it has been weight/adiposity, and higher serum glucose. It

determined that women tend to have better needs to be noted that research suggests the

cardiovascular health than their male counter- need for gender-specific indicators for cardio-

parts based on triglycerides and HDL. Another vascular health, as has been determined for

study showed similar gender differences among diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia [23].

African Americans only [22]. Women in our The influence of specific fat (saturated and

study also had higher serum HDL concentra- unsaturated) consumption was also not investi-

tions. This could have been influenced by the gated in our study. Since inflammation and oxi-

fact that less women smoked. Regarding other dative stress, caused by an unhealthy and pro-

factors related to dyslipidemia, men had higher inflammatory diet [20] are associated with ch-

LDL, VLDL, and Apo B. The cholesterol/HDL ronic diseases, related dietary markers would

ratio was higher for men, as well, while women have increased the strength of the study. How-

on average had higher cholesterol, adiponec- ever, the strengths and novelty of this study

tin, and Apo A1. Overall, women had better car- include the use of clinical and self-reported

diovascular health compared to men, possibly data, as well as the multiple CVD assessments

due to the higher adiponectin and Apo A1 con- and inclusion of multiple confounders, includ-

centrations. As a leading risk factor, high glu- ing medication use.

135 Am J Cardiovasc Dis 2016;6(3):129-137

Diabetes and cardiovascular health among African Americans

In conclusion, our study showed that men had [4] Oterdoom LH, de Vries AP, Gansevoort RT, de

higher serum glucose, the latter contributing to Jong PE, Gans RO, Bakker SJ. Fasting insulin is

a higher 10-year risk scores for CVD; therefore, a stronger cardiovascular risk factor in women

we speculate that T2DM as reflected by high than in men. Atherosclerosis 2009; 203: 640-

646.

glucose was a leading factor in cardiovascular

[5] Lin SX, Carnethon M, Szklo M, Bertoni A. Ra-

health when participants were separated by

cial/ethnic differences in the association of

gender. Lifestyle choices such as diet and triglycerides with other metabolic syndrome

smoking, played a role in influencing the CVD components: The multi-ethnic study of athero-

risk indicating that lifestyle factors may need to sclerosis. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 2011; 9:

be altered to improve cardiovascular health. 35-40.

[6] Winston GJ, Barr RG, Carrasquillo O, Bertoni

Acknowledgements AG, Shea S. Sex and racial/ethnic differences

in cardiovascular disease risk factor treatment

This study was supported by the National and control among individuals with diabetes

Institute on Minority Health & Health Disparities, in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis

National Institutes of Health R24MD002807 (mesa). Diabetes Care 2009; 32: 1467-1469.

(P.A. Ralston, PI). The content is solely the [7] Bertoni AG, Clark JM, Feeney P, Yanovski SZ,

responsibility of the authors and does not nec- Bantle J, Montgomery B, Safford MM, Herman

essarily represent the official views of the WH, Haffner S. Suboptimal control of glycemia,

blood pressure, and ldl cholesterol in over-

National Institute on Minority Health & Health

weight adults with diabetes: The look ahead

Disparities or the National Institutes of Health.

study. J Diabetes Complications 2008; 22: 1-9.

The participants of this study are greatly [8] Truesdell D, Shin H, Liu PY, Ilich JZ. Vitamin d

appreciated. status and framingham risk score in over-

weight postmenopausal women. J Womens

Disclosure of conflict of interest Health (Larchmt) 2011; 20: 1341-1348.

[9] Mayer-Davis EJ, Levin S, Bergman RN, DAgo-

None. stino RB Jr, Karter AJ, Saad MF; Insulin Resis-

tance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS). Insulin se-

Address correspondence to: Dr. Jasminka Z Ilich, cretion, obesity, and potential behavioral influ-

Department of Nutrition, Food and Exercise Sci- ences: Results from the insulin resistance

ences, Florida State University, 120 Convocation atherosclerosis study (iras). Diabetes Metab

Way, 418 Sandels, Tallahassee, FL 32306-1493, Res Rev 2001; 17: 137-145.

USA. Tel: 850-645-7177; Fax: 850-645-5000; [10] Matsushita Y, Yokoyama T, Homma T, Tanaka

E-mail: jilichernst@fsu.edu H, Kawahara K. Relationship between the abil-

ity to recognize energy intake and expenditure,

References and blood sugar control in type 2 diabetes mel-

litus patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2005;

[1] Bertoia ML, Allison MA, Manson JE, Freiberg 67: 220-226.

MS, Kuller LH, Solomon AJ, Limacher MC, [11] Carson JA, Michalsky L, Latson B, Banks K,

Johnson KC, Curb JD, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Tong L, Gimpel N, Lee JJ, Dehaven MJ. The car-

Eaton CB. Risk factors for sudden cardiac diovascular health of urban african americans:

death in post-menopausal women. J Am Coll Diet-related results from the genes, nutrition,

Cardiol 2012; 60: 2674-2682. exercise, wellness, and spiritual growth (good-

[2] Paramsothy P, Knopp RH, Bertoni AG, Blumen- news) trial. J Acad Nutr Diet 2012; 112: 1852-

thal RS, Wasserman BA, Tsai MY, Rue T, Wong 1858.

ND, Heckbert SR. Association of combinations [12] LaVeist T, Thorpe R Jr, Bowen-Reid T, Jackson J,

of lipid parameters with carotid intima-media Gary T, Gaskin D, Browne D. Exploring health

thickness and coronary artery calcium in the disparities in integrated communities: Over-

mesa (multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis). J view of the ehdic study. J Urban Health 2008;

Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 56: 1034-1041. 85: 11-21.

[3] Mete M, Wilson C, Lee ET, Silverman A, Russell [13] LaVeist TA, Thorpe RJ Jr, Galarraga JE, Bower

M, Stylianou M, Umans JG, Wang W, Howard KM, Gary-Webb TL. Environmental and socio-

WJ, Ratner RE, Howard BV, Fleg JL. Relation- economic factors as contributors to racial dis-

ship of glycemia control to lipid and blood pres- parities in diabetes prevalence. J Gen Intern

sure lowering and atherosclerosis: The sands Med 2009; 24: 1144-1148.

experience. J Diabetes Complications 2011; [14] Mount DL, Davis C, Kennedy B, Raatz S, Dot-

25: 362-367. son K, Gary-Webb TL, Thomas S, Johnson KC,

136 Am J Cardiovasc Dis 2016;6(3):129-137

Diabetes and cardiovascular health among African Americans

Espeland MA. Factors influencing enrollment [19] McGuinness OP, Myers SR, Neal D, Cherrington

of african americans in the look ahead trial. AD. Chronic hyperinsulinemia decreases insu-

Clin Trials 2012; 9: 80-89. lin action but not insulin sensitivity. Metabo-

[15] Zeno SA, Deuster PA, Davis JL, Kim-Dorner SJ, lism 1990; 39: 931-937.

Remaley AT, Poth M. Diagnostic criteria for [20] Ilich JZ, Kelly OJ, Kim Y, Spicer MT. Low-grade

metabolic syndrome: Caucasians versus afri- chronic inflammation perpetuated by modern

can-americans. Metab Syndr Relat Disord diet as a promoter of obesity and osteoporosis.

2010; 8: 149-156. Arh Hig Rada Toksikol 2014; 65: 139-148.

[16] Ralston PA, Lemacks JL, Wickrama KK, Young- [21] Liu PY, Hornbuckle LM, Panton LB, Kim JS, Ilich

Clark I, Coccia C, Ilich JZ, Harris CM, Hart CB, JZ. Evidence for the association between ab-

Battle AM, ONeal CW. Reducing cardiovascu- dominal fat and cardiovascular risk factors in

lar disease risk in mid-life and older african overweight and obese african american wom-

americans: A church-based longitudinal inter- en. J Am Coll Nutr 2012; 31: 126-132.

vention project at baseline. Contemp Clin Trials [22] Bidulescu A, Liu J, Hickson DA, Hairston KG,

2014; 38: 69-81. Fox ER, Arnett DK, Sumner AE, Taylor HA, Gib-

[17] Muntner P, He J, Chen J, Fonseca V, Whelton bons GH. Gender differences in the associa-

PK. Prevalence of non-traditional cardiovascu- tion of visceral and subcutaneous adiposity

lar disease risk factors among persons with with adiponectin in african americans: The

impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tol- jackson heart study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord

erance, diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome: 2013; 13: 9.

Analysis of the third national health and nutri- [23] Agrawal S, Van Eyk J, Sobhani K, Wei J, Bairey

tion examination survey (nhanes iii). Ann Epi- Merz CN. Sex, myocardial infarction, and the

demiol 2004; 14: 686-695. failure of risk scores in women. J Womens

[18] Osei K, Gaillard T, Schuster D. Plasma adipo- Health (Larchmt) 2015; 24: 859-861.

nectin levels in high risk african-americans

with normal glucose tolerance, impaired glu-

cose tolerance, and type 2 diabetes. Obes Res

2005; 13: 179-185.

137 Am J Cardiovasc Dis 2016;6(3):129-137

You might also like

- Journal Medicine: The New EnglandDocument9 pagesJournal Medicine: The New EnglandFernanda Araújo AvendanhaNo ratings yet

- Womenshealth & NutritionDocument5 pagesWomenshealth & Nutritionbragaru.vladNo ratings yet

- Causes of Changes in Carotid Intima-Media Thickness: A Literature ReviewDocument10 pagesCauses of Changes in Carotid Intima-Media Thickness: A Literature ReviewSorin ParalescuNo ratings yet

- Trends in Cardiovascular Health Metrics in Obese Adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 1988 - 2014Document20 pagesTrends in Cardiovascular Health Metrics in Obese Adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 1988 - 2014Desy YardinaNo ratings yet

- Primary and Secondary Prevention of Coronary Artery DiseaseDocument24 pagesPrimary and Secondary Prevention of Coronary Artery DiseaseNatalia GeofaniNo ratings yet

- Primary and Secondary Prevention of Coronary Artery Disease - Overview, Risk AsseDocument32 pagesPrimary and Secondary Prevention of Coronary Artery Disease - Overview, Risk Asseליסה לרנרNo ratings yet

- Dose-Response Association of Uncontrolled Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors With Hyperuricemia and GoutDocument8 pagesDose-Response Association of Uncontrolled Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors With Hyperuricemia and GoutxoxotheNo ratings yet

- ANNALS DyslipidemiaDocument16 pagesANNALS Dyslipidemiaewb100% (1)

- Cuadro de Horarios Paa RellenarDocument7 pagesCuadro de Horarios Paa RellenarLuis ChangaNo ratings yet

- Thừa cân, béo phì liên quan đến nhiều loại bệnh tật nguy hiểm-wed HarvardDocument24 pagesThừa cân, béo phì liên quan đến nhiều loại bệnh tật nguy hiểm-wed HarvardNam NguyenHoangNo ratings yet

- Serum Alpha-Carotene Concentrations and Risk of Death Among US AdultsDocument9 pagesSerum Alpha-Carotene Concentrations and Risk of Death Among US AdultsCherry San DiegoNo ratings yet

- Stoke NutritionDocument14 pagesStoke Nutritionapi-150223943No ratings yet

- Dyson LineDocument10 pagesDyson LineSharly DwijayantiNo ratings yet

- Final Research ProjectDocument21 pagesFinal Research Projectapi-339312954No ratings yet

- Ni Hms 366201Document17 pagesNi Hms 366201Habiburrahman EffendyNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis of Early Risks, Management of Risks, and Reduction of Vascular DiseasesDocument11 pagesDiagnosis of Early Risks, Management of Risks, and Reduction of Vascular DiseasesasclepiuspdfsNo ratings yet

- Harmonizing The Metabolic SyndromeDocument7 pagesHarmonizing The Metabolic SyndromeCarlos_RuedasNo ratings yet

- IV Abra DineDocument13 pagesIV Abra DinelilisNo ratings yet

- Review ArticleDocument14 pagesReview ArticlePanji Agung KhrisnaNo ratings yet

- Andrew Maxwell, M.D.: From: Sent: To: SubjectDocument4 pagesAndrew Maxwell, M.D.: From: Sent: To: SubjectHeart of the Valley, Pediatric CardiologyNo ratings yet

- Hypercholesterolemia Among Children: When Is It High, and When Is It Really High?Document4 pagesHypercholesterolemia Among Children: When Is It High, and When Is It Really High?Brenda CaraveoNo ratings yet

- The Role of Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolic Syndrome in StrokeDocument7 pagesThe Role of Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolic Syndrome in StrokeEmir SaricNo ratings yet

- Novel Pathological Implications of Serum Uric Acid - 2023 - Diabetes Research AnDocument8 pagesNovel Pathological Implications of Serum Uric Acid - 2023 - Diabetes Research Analerta.bfcmNo ratings yet

- Hypertension in PregnancyDocument5 pagesHypertension in PregnancyLalita Eka Pervita SariNo ratings yet

- Ahei & HeiDocument12 pagesAhei & HeiBushra KainaatNo ratings yet

- Artikel 4 - CohortDocument9 pagesArtikel 4 - Cohort048Auliatur RohmahNo ratings yet

- Assessment of College Students Awareness and Knowledge About Conditions Relevant To Metabolic SyndromeDocument15 pagesAssessment of College Students Awareness and Knowledge About Conditions Relevant To Metabolic SyndromeManimegalai SNo ratings yet

- Background of The StudyDocument10 pagesBackground of The StudyReimond VinceNo ratings yet

- What Is A Cardiovascular Risk and Factors?Document7 pagesWhat Is A Cardiovascular Risk and Factors?Rahul SharmaNo ratings yet

- Hostility and The Metabolic Syndrome in Older Males: The Normative Aging StudyDocument10 pagesHostility and The Metabolic Syndrome in Older Males: The Normative Aging StudymrclpppNo ratings yet

- Framingham Risk Score SaDocument8 pagesFramingham Risk Score Saapi-301624030No ratings yet

- Raman, G 2019Document12 pagesRaman, G 2019Nicolás MurilloNo ratings yet

- AHA/ADA Scientific StatementDocument29 pagesAHA/ADA Scientific StatementpukpigjNo ratings yet

- Diabetes Hypertension Obesity: PathophysiologyDocument3 pagesDiabetes Hypertension Obesity: PathophysiologyDevy AndikaNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Egg Limitations On CHD PDFDocument9 pagesThe Impact of Egg Limitations On CHD PDFAndri NugrahaNo ratings yet

- Healthy Lifestyle and The Risk of Stroke in Women: BackgroundDocument11 pagesHealthy Lifestyle and The Risk of Stroke in Women: BackgroundGlaiza CzarinaNo ratings yet

- Medical Tribune May 2013Document39 pagesMedical Tribune May 2013Marissa WreksoatmodjoNo ratings yet

- VITAMINA D y Riesgo CardiovascularDocument12 pagesVITAMINA D y Riesgo CardiovascularAngusNo ratings yet

- CA Cancer J ClinDocument29 pagesCA Cancer J ClinanshunigamNo ratings yet

- Polygenic Hypercholesterolemia: Causes, Risks & TreatmentDocument6 pagesPolygenic Hypercholesterolemia: Causes, Risks & TreatmentSamhitha Ayurvedic ChennaiNo ratings yet

- 4 - Health Consequences of Obesity 2012Document5 pages4 - Health Consequences of Obesity 2012Mateus CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- AbstractDocument1 pageAbstractmich__aishkaiNo ratings yet

- PIIS0002934311002920 CGHDocument10 pagesPIIS0002934311002920 CGHJulianda Dini HalimNo ratings yet

- Cost-Effectiveness of Hypertension Therapy According To 2014 GuidelinesDocument9 pagesCost-Effectiveness of Hypertension Therapy According To 2014 GuidelinesIsti YaniNo ratings yet

- Https/www-Uptodate-Com Consultaremota Upb Edu Co/contents/management-Of-CDocument34 pagesHttps/www-Uptodate-Com Consultaremota Upb Edu Co/contents/management-Of-CMichael Amarillo CorreaNo ratings yet

- Nutrients: Dietary Interventions For Gout and E Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Systematic ReviewDocument19 pagesNutrients: Dietary Interventions For Gout and E Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Systematic ReviewVika NovikaNo ratings yet

- Science Fair Final ReportDocument16 pagesScience Fair Final ReportNishorgo SarkarNo ratings yet

- Modified Mediterranean Diet Score and Cardiovascular Risk in A North American Working PopulationDocument10 pagesModified Mediterranean Diet Score and Cardiovascular Risk in A North American Working Populationapi-356847931No ratings yet

- Gastroenteritis Outbreak Tied To Later Health Problems: HealthdayDocument5 pagesGastroenteritis Outbreak Tied To Later Health Problems: HealthdayJammae RubillosNo ratings yet

- NAFLDDocument17 pagesNAFLDJirran CabatinganNo ratings yet

- Zalesin 2008Document22 pagesZalesin 2008Dinti wardaNo ratings yet

- 2019 ACC - AHA Guideline On The Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease - American College of CardiologyDocument9 pages2019 ACC - AHA Guideline On The Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease - American College of CardiologyYasinta FebrianaNo ratings yet

- ACS Guidelines PDFDocument38 pagesACS Guidelines PDFGabriel MateusNo ratings yet

- 6.vol5 Issue2 2017 MS 15392Document4 pages6.vol5 Issue2 2017 MS 15392iamsleepless007No ratings yet

- Cardiometabolic Syndrome PipinDocument15 pagesCardiometabolic Syndrome Pipinspider_mechNo ratings yet

- Evidence Based Cardiology 4th EdDocument424 pagesEvidence Based Cardiology 4th EdROGER LUDEÑA SALAZARNo ratings yet

- 2017, Guerra-Silva IJCDocument7 pages2017, Guerra-Silva IJCNatalia Maria Maciel GuerraNo ratings yet

- Medical Hazards of Obesity: Ann Intern Med. 1993 119 (7 PT 2) :655-660Document6 pagesMedical Hazards of Obesity: Ann Intern Med. 1993 119 (7 PT 2) :655-660David WheelerNo ratings yet

- nutrients-10-01385Document16 pagesnutrients-10-01385Alex GutiérrezNo ratings yet

- Daftar Dosis Dan Sediaan ObatDocument5 pagesDaftar Dosis Dan Sediaan ObatVenessa Rudy Pranata97% (38)

- Drug Doses 2017Document127 pagesDrug Doses 2017Yuliawati HarunaNo ratings yet

- Daftar Dosis Dan Sediaan ObatDocument5 pagesDaftar Dosis Dan Sediaan ObatVenessa Rudy Pranata97% (38)

- Westeergard Focus On Abnormal Air PDFDocument8 pagesWesteergard Focus On Abnormal Air PDFIndah RismandasariNo ratings yet

- CR 07 167Document6 pagesCR 07 167Indah RismandasariNo ratings yet

- Book 1Document2 pagesBook 1Indah RismandasariNo ratings yet

- Ojog 2016042617575247Document7 pagesOjog 2016042617575247Mahdiah JabailusNo ratings yet

- WikiAbdominal Pain PDFDocument6 pagesWikiAbdominal Pain PDFIndah RismandasariNo ratings yet

- DR P Nel The Diagnostic Role of Sonar and CT-scan inDocument21 pagesDR P Nel The Diagnostic Role of Sonar and CT-scan inIndah RismandasariNo ratings yet

- Acute Abdomen Pre and Post-Laparotomy DiagnosisDocument10 pagesAcute Abdomen Pre and Post-Laparotomy DiagnosisIndah RismandasariNo ratings yet

- Heart: Yvan Patrick AkréDocument1 pageHeart: Yvan Patrick AkréIndah RismandasariNo ratings yet

- Poster52 PDFDocument1 pagePoster52 PDFIndah RismandasariNo ratings yet

- 2016 Article 291Document4 pages2016 Article 291Indah RismandasariNo ratings yet

- HPV 180Document9 pagesHPV 180Indah RismandasariNo ratings yet

- E003682 FullDocument13 pagesE003682 FullIndah RismandasariNo ratings yet

- Sepsis N Endothelial PermeabilityDocument3 pagesSepsis N Endothelial PermeabilityIndah RismandasariNo ratings yet

- E004758 FullDocument11 pagesE004758 FullIndah RismandasariNo ratings yet

- 2017 Article 482Document8 pages2017 Article 482Indah RismandasariNo ratings yet

- CHT Acfa Boys Z 3 5Document1 pageCHT Acfa Boys Z 3 5Rivadin NurwanNo ratings yet

- 2016 Article 442Document8 pages2016 Article 442Indah RismandasariNo ratings yet

- 2016 Article 189Document12 pages2016 Article 189Indah RismandasariNo ratings yet

- 2017 Article 478Document10 pages2017 Article 478Indah RismandasariNo ratings yet

- Liquorice: A Root Cause of Secondary Hypertension: Ravi Varma and Calum N. RossDocument3 pagesLiquorice: A Root Cause of Secondary Hypertension: Ravi Varma and Calum N. RossIndah RismandasariNo ratings yet

- Z Scores PDFDocument29 pagesZ Scores PDFIndah RismandasariNo ratings yet

- CHT Acfa Boys Z 3 5Document1 pageCHT Acfa Boys Z 3 5Rivadin NurwanNo ratings yet

- ABC of BurnDocument3 pagesABC of BurnJokevin PrasetyadhiNo ratings yet

- WHO Grow Chart TB+U Girl 5-19Document1 pageWHO Grow Chart TB+U Girl 5-19Kartika AnggakusumaNo ratings yet

- BMJ BurnDocument3 pagesBMJ BurnNila SariNo ratings yet

- WikiAbdominal PainDocument6 pagesWikiAbdominal PainIndah RismandasariNo ratings yet

- Acute Abdominal Emergencies GuideDocument126 pagesAcute Abdominal Emergencies GuidekityamuwesiNo ratings yet

- Naming, Labeling, and Packaging of Pharmaceuticals: Special FeaturesDocument9 pagesNaming, Labeling, and Packaging of Pharmaceuticals: Special FeaturesjovanaNo ratings yet

- Methodical Instructions: For The Practical Classes in Pharmacology TopicDocument3 pagesMethodical Instructions: For The Practical Classes in Pharmacology TopicSahil SainiNo ratings yet

- Diagnosing Secondary and Primary Headache Disorders: Review ArticleDocument14 pagesDiagnosing Secondary and Primary Headache Disorders: Review ArticleMD IurieNo ratings yet

- Hiperakusis 2015Document20 pagesHiperakusis 2015Abdur ShamilNo ratings yet

- TeratologyDocument36 pagesTeratologySafera RezaNo ratings yet

- Training Design AprilDocument3 pagesTraining Design AprilZed P. EstalillaNo ratings yet

- Quality of life and insomnia treatmentDocument14 pagesQuality of life and insomnia treatmentAkhmad VauwazNo ratings yet

- First Aid Manual Rev 0Document77 pagesFirst Aid Manual Rev 0Vinayak KaujalgiNo ratings yet

- Psychiatric History and Mental Status ExamDocument81 pagesPsychiatric History and Mental Status ExamErsido SamuelNo ratings yet

- Assessment ToolDocument13 pagesAssessment Toolal gulNo ratings yet

- KARDEX Case 1Document3 pagesKARDEX Case 1Juviely PremacioNo ratings yet

- Renal Failure and ItsDocument8 pagesRenal Failure and ItsSandra CalderonNo ratings yet

- Aapm TG 179Document18 pagesAapm TG 179Ahmet Kürşat ÖzkanNo ratings yet

- Clinical PathwayDocument91 pagesClinical PathwaytiganovNo ratings yet

- Fendo 13 967102Document9 pagesFendo 13 967102Vilma Gladis Rios HilarioNo ratings yet

- ShiatsuDocument20 pagesShiatsuMarko Ranitovic100% (1)

- Abnormal Psychology TestDocument7 pagesAbnormal Psychology TestCamae Snyder GangcuangcoNo ratings yet

- Internship 3Document4 pagesInternship 3Hirschmann Andro BoquilaNo ratings yet

- NASYTA DIFA FIRDAUS - Tabel Pengelompokkan AntibiotikDocument1 pageNASYTA DIFA FIRDAUS - Tabel Pengelompokkan AntibiotikNasyta Difa FirdausNo ratings yet

- 2 MergedDocument11 pages2 MergedMudasir ElahiNo ratings yet

- Smiths Medical Cadd Legacy Pca 6300 User Manual PDFDocument102 pagesSmiths Medical Cadd Legacy Pca 6300 User Manual PDFJr BraduNo ratings yet

- Heart Defects and Vascular Anomalies: Causes, Types and TreatmentDocument17 pagesHeart Defects and Vascular Anomalies: Causes, Types and TreatmentA.V.M.No ratings yet

- Bala MedicinalDocument23 pagesBala MedicinalJayesh BoroleNo ratings yet

- Wcet2016 Programme and Abstract BookDocument64 pagesWcet2016 Programme and Abstract BookMohyuddin A MaroofNo ratings yet

- Vaccine: Contents Lists Available atDocument9 pagesVaccine: Contents Lists Available atShabrina Amalia SuciNo ratings yet

- Respiratory FailureDocument8 pagesRespiratory FailureAnusha VergheseNo ratings yet

- CMC HIS User Manual SummaryDocument40 pagesCMC HIS User Manual Summarymanotiwa0% (1)

- Uterine Prolapse CaseDocument23 pagesUterine Prolapse CaseJonathan GnwNo ratings yet

- Basic of Ot 1Document2 pagesBasic of Ot 1shubham vermaNo ratings yet