Professional Documents

Culture Documents

SDJ 2016 09 01 PDF

Uploaded by

Dexter BluesOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

SDJ 2016 09 01 PDF

Uploaded by

Dexter BluesCopyright:

Available Formats

782 RESEARCH AND SCIENCE

Adrian Wlti

Adrian Lussi The effect of a chewing-intensive,

Rainer Seemann

high-fiber diet on oral halitosis

Dental Clinic of the University

of Bern

Clinic for restorative, preven-

tive, and pediatric dentistry

A clinical controlled study

CORRESPONDENCE

M Dent Med Adrian Wlti

Klinik fr Zahnerhaltung,

Prventiv- und Kinder

zahnmedizin

KEYWORDS

Freiburgstrasse 7

diet,

CH-3010 Bern

fiber,

Tel. +41 31 632 25 80

bad breath,

E-mail:

halitosis,

adrian.waelti@zmk.unibe.ch;

tongue coating

adrian.waelti@gmail.com

SWISS DENTAL JOURNAL SSO 126:

782788 (2016)

Accepted for publication:

23December 2015

SUMMARY

Tongue coating is the most common cause of amodified Winkel index, and the mouth sensation

oral halitosis and eating results in its reduction. was evaluated subjectively by the subjects.

Only limited data are available on the effect of In both the test and the control phase, a statisti-

different food items on tongue coating and hali- cally significant reduction of all selected parame-

tosis. Therefore, the aim of this study was to ters was detected (p<0.05). Only for the organo-

investigate the effect of a single consumption leptic assessment of halitosis was a statistically

of food with high fiber content versus low fiber significantly higher reduction found after con-

content on halitosis parameters. sumption of a high-fiber meal compared to the

Based on a randomized clinical cross-over study, control meal (p<0.05).

20subjects were examined over a period of In conclusion, the consumption of the meals in

2.5hours after consumption of a high-fiber and this study resulted in an at least 2.5-hour re

alow-fiber meal. The determination of volatile duction of oral halitosis. The chewing-intensive

sulfur compounds (VSC) was performed using a (high-fiber) meal even resulted in a slightly higher

Halimeter, and the organoleptic assessment of reduction of oral halitosis in terms of organoleptic

halitosis was done on the basis of a distance assessment (p<0.05).

index. The tongue coating was determined using

SWISS DENTAL JOURNAL SSO VOL 126 9 2016

P

RESEARCH AND SCIENCE 783

Introduction coating and a VSC concentration of at least 150ppb (parts per

The term halitosis refers to bad breath, Foetor ex ore or oral billion) with an empty stomach in the morning. Additionally,

malodour (Seemann et al. 2014). According to epidemiological the participants were asked to refrain from any tongue-cleans-

studies, about a quarter of the population suffers from bad ing measures and the consumption of any products containing

breath (Liu et al. 2006, Bornstein et al. 2009). Halitosis can de- onions or garlic two days before the screening. It was prohibit-

velop intra- as well as extraorally. Different examinations have ed to eat, drink, or perform toothbrushing or mouthrinsing on

shown that a bacterial decomposition of organic material inside the day of the examination. Gum and hard candy or lozenges

the oral cavity (mouth) is the cause of halitosis in 85% to 90% were forbidden as well.

of cases (Tonzetich &Richter 1964, Tonzetich 1978, Delanghe et

al. 1999, Rosenberg &Leib 1997, Seemann et al. 2014). This form Exclusion criteria

of halitosis is called oral halitosis (Yaegaki &Ciol 2000, Seemann Potential participants were excluded from the study if they

et al. 2014). were smokers, had allergies or intolerances to a component of

Volatile sulfur compounds (VSC), which are produced by the meal, had existing periodontal diseases, had suffered from

Gram-negative anaerobic bacteria, are responsible for the diseases of the ear, nose, throat, or mouth within the last three

development of the unpleasant odor (Tonzetich &Richter 1964, months, or had had any serious prior or recurring disease in

Tonzetich 1971). These VSCs are mainly the chemical com- any of these areas. Individuals with an American Society of

pounds hydrogen sulfide HS, methyl mercaptan (CH)SH, and Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification of 36 (severe systemic

dimethyl sulfide (CH)S (Tonzetich &Richter 1964, Tonzetich disease to moribund state), or who had been on antibiotics

1971). According to a number of estimates, about two-thirds within the last three weeks or had consumed foods containing

of all oral microbes are located on the dorsum (back) of the onions or garlic within the last two days before the examina-

tongue. The tongue coating itself mainly consists of blood and tion were also excluded.

saliva particles, food residue, exfoliated epithelial cells, and

bacteria (De Boever &Loesche 1995). Of the Gram-negative Study design and clinical execution

anaerobic bacteria mentioned above, Tannerella forsythia, The study was conducted according to a crossover design, so

Treponema denticola, and Porphyromonas gingivalis deserve that every participant was part of both the test and the control

particular mention (Bosy et al. 1994). Arough tongue surface, group. There was a wash-out period of at least two weeks be-

characterized by numerous dimples and fissures, facilitates tween the test and the control phase to avoid possible carry-

tongue coating and consequently halitosis development (De over effects. While one half began with the test, i.e., chewing-

Boever &Loesche 1995). intensive/high-fiber meal (groupA), the other half started

Despite only a moderate level of evidence, mechanical with the control, i.e., less chewing-intensive/low-fiber meal

cleansing which removes the obvious tongue coating is (groupB).

one of the most commonly used therapeutic measures. This The participants arrived at the clinic on the first day of the

leads to a significant reduction of VSCs and thus a reduction of examination, having complied with the inclusion criteria.

halitosis (Tonzetich &Ng 1976, Tonzetich 1978, Van der Sleen They were divided into the two groups by drawing lots.

2010, Seemann et al. 2014). This method can be enhanced by Afterwards, the baseline VSC concentration was measured

using certain chemicals, such as chlorhexidine or zinc com- using a Halimeter, and an organoleptic evaluation of halito-

pounds (Dadamio et al. 2013a, Dadamio et al. 2013b, Slot et al. sis was performed using a distance-based scale (Seemann

2015). It is also known that the VSC concentration decreases 2006, Seemann et al. 2014). Additionally, a photo was taken

significantly during a meal and increases afterwards again of the tongue, and the participant had to indicate his/her

(Yaegaki et al. 2012). Additionally, the VSC level is higher after current mouth sensation using a visual analog scale (VAS).

anights sleep, due to the reduced flow of saliva and the result- Subsequently, the participants consumed their entire re-

ing increase in the bacterial load. This is referred to as morning spective meal. After the meal had been ingested, the same

breath (Tonzetich 1978). parameters that were examined in the baseline measure-

The present authors are not aware of any scientific research ment were determined again. In the ensuing 2.5hours,

from the German or English literature that describes the effects the VSC concentration was measured at different intervals

of a special high-fiber, chewing-intensive diet compared to a (Tab.I) using a Halimeter. Finally, all the parameters of the

low-fiber, less chewing-intensive one on the concentration of baseline and the post-ingestion measurement were deter-

VSCs, halitosis, and tongue coating. Only an opinion (not an mined again. For the exact time schedule of the measure-

analysis or examination) was given that foods such as hard ments, see TableI.

bread, dry cereal, raw vegetables, and fibrous meat could re-

move tongue coating (Massler 1980). Hence, the aim of this Measurements with the Halimeter

study was to examine the effect of a one-time consumption The concentration of VSC was measured using a Halimeter

of high-fiber, chewing-intensive food on the concentration of (Interscan Corporation, Simi Valley, CA, USA). This device

VSCs, halitosis, tongue coating, and the feeling in the mouth. reacts mainly to an increase of the three major VSCs: hydrogen

The hypothesis was that halitosis could be reduced longer and sulfide, methyl mercaptan, and dimethyl sulfide. Neither ca-

more significantly through a chewing-intensive, high-fiber daverine, putrescine, indole nor skatole, about which there is

meal. debate as to whether or not they are involved in causing halito-

sis, are detected by the Halimeter. For the measurement pro-

Materials and methods cess, a plastic straw is inserted about 34cm into the patients

The participants were 20healthy people chosen from the regu- slightly opened mouth. The sensor is supplied with air from

lar pool of patients, as well as students and employees of the inside the mouth by an internal pump until a VSC maximum

Dental Clinic of the University of Bern, who had visible tongue is reached (Rosenberg et al. 1991a).

SWISS DENTAL JOURNAL SSO VOL 126 9 2016

P

784 RESEARCH AND SCIENCE

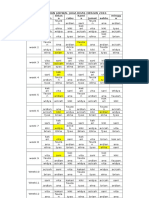

Tab.I Procedure on examination days 1 and 2

Examination day 1 Examination day 2

Time point Parameters examined Time point Parameters examined

Baseline ppb VSC using the Halimeter Baseline ppb VSC using the Halimeter

halitosis (organoleptic) halitosis (organoleptic)

tongue coating tongue coating

subjective mouth sensation subjective mouth sensation

Subject group A: Test meal Subject group A: Control meal

Subject group B: Control meal Subject group B: Test meal

Immediately after the meal ppb VSC using the Halimeter Immediately after the meal ppb VSC using the Halimeter

halitosis (organoleptic) halitosis (organoleptic)

tongue coating tongue coating

subjective mouth sensation subjective mouth sensation

10 min. after the meal ppb VSC using the Halimeter 10 min. after the meal ppb VSC using the Halimeter

30 min. after the meal ppb VSC using the Halimeter 30 min. after the meal ppb VSC using the Halimeter

60 min. after the meal ppb VSC using the Halimeter 60 min. after the meal ppb VSC using the Halimeter

90 min. after the meal ppb VSC using the Halimeter 90 min. after the meal ppb VSC using the Halimeter

120 min. after the meal ppb VSC using the Halimeter 120 min. after the meal ppb VSC using the Halimeter

150 min. after the meal ppb VSC using the Halimeter 150 min. after the meal ppb VSC using the Halimeter

halitosis (organoleptic) halitosis (organoleptic)

tongue coating tongue coating

subjective mouth sensation subjective mouth sensation

ppb VSC = parts per billion volatile sulfur compounds

Organoleptic evaluation of halitosis Subjective evaluation of mouth sensation

Organoleptic means using ones own sense of smell to perceive Before and after the meal, as well as at the end of the morning

halitosis and to classify it according to strength (Rosenberg et of examination, the participants were asked to evaluate their

al. 1991b, Greenman et al. 2014). For this study, a simple dis- current mouth sensation on a VAS. The scale ranged from very

tance scale was used; the patient counts from one to ten at a pleasant (score0) to extremely unpleasant (score10) along

normal volume, and the strength of halitosis is classified into 100mm on a ruler, allowing scores to be determined to the

four different degrees (Seemann 2006, Bornstein et al. 2009, See- nearest tenth.

mann et al. 2014):

degree 0 = no halitosis detected Meals and calculation of the amount of fiber

degree 1 = halitosis detected at a distance of 10cm For the meals, breakfast rolls with certain amounts of fiber were

degree 2 = halitosis detected at a distance of 30cm made. To precisely calculate the fiber content, the nutritional

degree 3 = halitosis detected at a distance of 100cm

Evaluation of tongue coating

Tab.II Meal components

A modified Winkel tongue-coating index (WTCI) was used to

quantify the tongue coating (Winkel et al. 2003). This index Components

classifies the visible amount of tongue coating as a sum-score of

imaginary sextants of the tongue. The modification consisted of Test meal 1 whole-grain bread roll (high wheat bran

changing the original code2 and adding code3. This resulted in (high-fiber and content)

chewing-intensive Apple (raw, peeled)

the following evaluation system being used for each sextant:

Blackberry jam

0: no tongue coating Butter

1: slight tongue coating Water

2: significant tongue coating in up to 2/3 of the sextant

3: significant tongue coating in more than 2/3 of the sextant Control meal 1 white bread roll

(low-fiber and less Cooked apples

chewing-intensive) Quince jelly

The evaluation was performed by two dentists familiar with the

Butter

index, using photos of the tongues presented to them in a ran-

Water

dom order.

SWISS DENTAL JOURNAL SSO VOL 126 9 2016

P

RESEARCH AND SCIENCE 785

value databank of the Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office determining the tongue coating index before and after the

(BLV, www.naehrwertdaten.ch) was consulted or, if available, meal, as well as after the last VSC measurement in both

the manufacturers information on packaging of the individual groups

product was used. subjective evaluation of the mouth sensation before and after

The different components of both of the meals are presented the meal, as well as after the last VSC measurement in both

in TableII. The exact calculation of the amount of fiber in the groups

foods can also be found in TableIII. P-values <0.05 were deemed significant.

Ethics The Wilcoxon signed-rank test and a non-parametric longitu-

In accordance with the Helsinki Declaration, the participants dinal ANOVA by Brunner and Langer were used for the statisti-

were informed about the exact procedure of the study and gave cal analysis (Brunner et al. 2002), employing Rversion3.2.2

their written consent, as required by the guidelines. The study software (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna,

was approved by the Ethics Commission of Bern (KEK-Ge- Austria).

suchs-Nr.: 244/12).

Results

Statistics All of the participants met the inclusion criteria and were ad-

The primary outcome was the percent decrease of the VSC val- mitted to the study.

ues after a chewing-intensive, high-fiber meal and a less chew- When comparing the reduction of the VSC value between

ing-intensive, low-fiber meal (groupsA andB). the first and second measurements (baseline and directly

The secondary outcome was composed of: after ingesting the meal), no significant difference between

seven VSC measurements over time in both groups, each in the test and control group was found (Fig.1A). The same is

relation to the first VSC measurement true of the comparison between the first and eighth measure-

organoleptic evaluation before and after the meal, as well as ments (baseline and at the end of the examination morning)

after the last VSC measurement in both groups (Fig.1B).

Tab.III Dietary fiber content in g by product and ingredient

Product Ingredients Quantity (g) Dietary fiber Effective dietary

(g/100g) fiber (g)

Meal A Wheat bran Whole-wheat flour 34 11 3.74

(test) bread roll

Wheat bran 37 49.3 18.24

Water 45 0 0

Yeast 9 6.9 0.62

Salt 2 0 0

Butter unlimited 0 0

Blackberry jam 30 4 1.2

Apple, raw 100 2.1 2.1

Total 25.90

Meal B White bread roll White flour 75 2.5 1.88

(control)

Milk 38 0 0

Yeast 9 6.9 0.62

Salt 2 0 0

Butter unlimited 0 0

Quince jelly 30 0.5 0.15

Cooked apples 100 2.76 2.76

Total 5.41

SWISS DENTAL JOURNAL SSO VOL 126 9 2016

P

786 RESEARCH AND SCIENCE

The ingestion of a meal lowered the score of all of the exam- high-fiber meal led to a statistically significantly greater re-

ined parameters (VSC, organoleptic evaluation of halitosis, duction of the organoleptically perceptible halitosis (p<0.05).

tongue coating, and subjective mouth sensation) significantly, The other three parameters were compared directly (test vs.

independent of whether it was the test or the control meal control meal) as well, but no significant differences were

(p<0.05). In a direct comparison, the chewing-intensive, found. (Fig.2AD).

A B

Difference in VSC values [ppb]

Difference in VSC values [ppb]

Fig.1 Reduction of the absolute VSC

values immediately after ingesting

the meal compared to baseline (A),

control test control test reduction of the absolute VSC values

at the end of the examination morn-

ing compared to baseline (B) [ppb]

A B

score

time point time point

C D

score

Fig.2 (in means): Chronological se-

quence of the VSC measurement (A),

the organoleptic halitosis measure-

time point time point ment (B), the tongue-coating index

(C), and the subjective mouth sensa-

tion (D); (* = p<0.05)

P=test Y=control

SWISS DENTAL JOURNAL SSO VOL 126 9 2016 P

RESEARCH AND SCIENCE 787

Discussion

It is the general opinion that halitosis is reduced by eating (Yae-

gaki et al. 2012). This effect is due to the self-cleaning of the

mouth while chewing food. Considering the fact that the act of

chewing food has a self-cleaning effect on the mouth, and thus

on the dorsum of the tongue, it seems obvious that foods that

need to be chewed more intensively have a stronger self-clean-

ing effect than foods that require less chewing. Whether foods

with different chewing intensities actually influence the self-

cleaning process has not yet been examined. In this study, we

showed that chewing-intensive, high-fiber meals can signifi-

cantly improve the organoleptic score. The study hypothesis

was confirmed.

There is no universal definition for chewing intensity, chew-

ing-intensive, or chewing-intensive foods in the literature.

Thus, the term fibrous was used to describe different levels of

chewing intensity. Whether or not a food is perceived as high

fiber depends on the subjective assessment of the person eating

it. Fibrous, in terms of foods, refers to the dietary fibers, also

called roughage. Fiber is the plant-based component in a food

that cannot be digested (Suter 2008). However, the amount of

fiber alone does not determine the chewing intensity of the

food. An important additional factor is the consistency of the

food. Concerning fruit and vegetables, the chewing intensity

is influenced by whether they are consumed raw or cooked.

Acooked apple, for example, has a little more fiber than a raw

one, even though it is less chewing-intensive when cooked

(www.naehrwertdaten.ch). Bread rolls were made especially

for this study to ensure different amounts of fiber in two com-

parable products. Adrian Wlti

The present results confirmed that eating a meal reduces Fig.3 Division of the dorsum of the tongue into sextants to determine the

oral VSC concentrations and halitosis (Fig.1A andB, Fig.2B). modified Winkel tongue-coating index

There was a statistically significant improvement of the sub-

jective mouth sensation and reduction of the tongue coating

in both groups (Fig.2D andC). Even after 2.5hours, this effect study compares the relative differences rather than the abso-

could still be measured. However, comparing the effect of lute VSC values, and numerous measurements were made

foods with different levels of chewing intensity, no consistent within relatively short period of time, using the Halimeter was

pattern was found in this study. Hence, the effects of chew- justified.

ing-intensive, high-fiber foods should be observed over a lon- The non-significant parameters also tended to show a greater

ger period of time in a follow-up study. While there was no reduction after eating the test meal. Thus, we conclude that

statistically significant difference for the oral VSC, tongue chewing-intensive, high-fiber foods reduce oral halitosis more

coating, or subjective mouth sensation between the test and than less chewing-intensive, low-fiber foods. The slight effect

the control groups, the organoleptic evaluation of halitosis observed due to the choice of foods could also be seen in the

showed a statistically significantly greater reduction in the test evaluation of the tongue coating. Therefore, it was necessary to

group. The non-significant differences could be explained by modify the Winkel tongue-coating index in order to increase

the insufficient sample size of this pilot study. In a potential its sensitivity. Nonetheless, there was no significant difference

follow-up study, the sample size should be increased. Another between the test and the control phase. The sensitivity of the

reason could be that the chewing intensities of the two meals tongue-coating index was increased by adding an additional

were too similar, despite the extremely different amounts of score, resulting in the modified Winkel tongue-coating index

fiber. Both types of bread roll required thorough chewing; (mWTCI). An example is given in figure3. Using the original

therefore, any future examinations should compare foods re- index (0= no coating; 1= slight coating; 2= significant coat-

quiring little to no chewing, such as yoghurt or soup. It must ing), the results would have been as follows: 2/2/2/0/0/0;

also be discussed whether or not the Halimeter, despite its sum=6. Even though the amount of tongue coating in sex-

acceptable reproducibility, is capable of detecting minor dif- tants1 and3 appear to differ from the amount in sextant2 on

ferences, because the concentration of different sulfur com- the photos, this difference could not be described by the index.

pounds collectively determine the VSC value (in ppb) (Rosen- By applying the modified index (0= no coating; 1= slight coat-

berg et al. 1991b). Gas chromatographic measurements should ing; 2= significant coating in up to 2/3 of the sextant, 3= signifi-

be considered for future studies. However, this type of mea- cant coating in more than 2/3 of the sextant), the difference is

surement also has certain problems, e.g., the difficulties of quantifiable (2/3/2/0/0/0; sum =7). While the original index

standardized sample taking or not being able to provide real- may be sufficient for the dental praxis, we recommend making

time measurements, which are possible with a Halimeter appropriate modifications in clinical studies to increas its pre-

(Rosenberg et al. 1991a, Lalemann et al. 2014). Because this cision.

SWISS DENTAL JOURNAL SSO VOL 126 9 2016

P

788 RESEARCH AND SCIENCE

Conclusion ment faible en fibres alimentaires. La dtermination des com-

In conclusion, it can be said that ingesting the meals chosen in poss soufrs volatils (VSC = volatile sulphur compounds) a t

this study reduces oral halitosis for at least 2.5 hours. Adirect ralise en utilisant un Halimeter et lapprciation organo

comparison of the two meals showed that, the chewing-inten- leptique dun indice sur la distance. Le dpt bactrien sur la

sive, high-fiber meal led to a greater reduction of halitosis langue a t dtermin en utilisant lindice de Winkel, la sen-

(p<0.05). sation en bouche a t subjectivement value par les partici-

pants.

Rsum Indpendamment du repas consomm, une rduction statis-

Le dpt bactrien sur la langue est la cause la plus frquente de tiquement signifiante dans tous les paramtres mesurs a pu

lhalitose orale et manger conduit sa rduction. Linfluence tre dtect (p<0,05). Une comparaison directe des repas (faible

des diffrents aliments sur le dpt bactrien lingual et lhali- en fibres/riche en fibres) a montr une rduction statistique-

tose est jusqualors peu tudie. Le but de cette tude tait donc ment signifiante seulement pour lapprciation organoleptique

de comparer leffet de la nourriture riche en fibres alimentaires (p<0,05).

par rapport la nourriture faible en fibres alimentaires aprs une En rsum, nous pouvons conclure que la consommation des

consommation unique quant aux paramtres de lhalitose. repas slectionns dans cette tude a abouti une rduction

A laide dune tude clinique randomise croise, 20partici- dune halitose orale dau moins 2,5heures. Le repas plus intense

pants ont t examins sur une priode de 2,5heures aprs mcher (riche en fibres) a abouti une rduction plus forte de

lingestion dun repas riche en fibres alimentaires, respective- lhalitose orale (p<0,05).

References

BornsteinMM, KisligK, HotiBB, SeemannR, Lus- LiuXN, ShinadaK, ChenXC, ZhangBX, YaegakiK, SuterPM: Checkliste Ernhrung. 3.Aufl., Thieme-

siA: Prevalence of halitosis in the population of KawaguchyY: Oral malodor-related parameters Verlag, Stuttgart (2008)

the city of Bern, Switzerland: a study comparing in the Chinese general population. J Clin Peri-

TonzetichJ, RichterVJ: Evaluation of odoriferous

self-reported and clinical data. Eur J Oral Sci 117: odontol 33: 3136 (2006)

components of saliva. Arch Oral Biol 9: 3946

261267 (2009)

MasslerM: Geriatric dentistry: root caries in the (1964)

BosyA, KulkarniGV, RosenbergM, McCullochCA: elderly. J Prosthet Dent 44: 147149 (1980)

TonzetichJ: Direct gas chromatographic analysis

Relationship of oral malodor to periodontitis:

RosenbergM, SeptonI, EliI, Bar-NessR, Gelern of sulphur compounds in mouth air in man.

evidence of independence in discrete subpopu-

terI, BrennerS, GabbayJ: Halitosis measure- Arch Oral Biol 16: 587597 (1971)

lations. J Periodontol 65: 3746 (1994)

ment by an industrial sulphide monitor. J Peri-

TonzetichJ, NgSK: Reduction of malodor by oral

BrunnerE, DomhofS, LangerF: Nonparametric odontol 62: 487489 (1991)

cleansing procedures. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral

analysis of longitudinal data in factorial experi-

RosenbergM, KulkarnyGV, BosyA, McCullochCA: Pathol 42: 172181 (1976)

ments. Wiley-Verlag, New-York (2002)

Reproducibility and sensitivity of oral malodor

TonzetichJ: Oral malodor: an indicator of health

DadamioJ, Van TournoutM, TeughelsW, Dekey- measurements with a portable sulphide moni-

status and oral cleanliness. Int Dent J 28:

serC, CouckeW, QuirynenM: Efficacy of different tor. J Dent Res 70: 14361440 (1991)

309319 (1978)

mouthrinse formulations in reducing oral mal-

RosenbergM, LeibE: Experiences of an Israeli

odour: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Peri- Van der SleenMI, SlotDE, Van TrijffelE, Win-

malodor clinic. In: Bad breath. Research per-

odontol 40: 505513 (2013) kelEG, Van der WeijdenGA: Effectiveness of

spectives. Hrsg.: RosenbergM. Ramot Tel Aviv,

mechanical tongue cleaning on breath odour

DadamioJ, LalemanI, QuirynenM: The role of pp137148 (1997)

and tongue coating: a systematic review. Int J

toothpaste in oral malodor management.

SeemannR: Messung von Mundgeruch. In: Filip- Dent Hyg 8: 258268 (2010)

Monogr Oral Sci 23: 4560 (2013)

piA. (Hrsg.): Halitosis. Patienten mit Mund-

WinkelEG, RoldnS, Van WinkelhoffAJ, Herre-

De BoeverEH, LoescheWJ: Assessing the contri- geruch in der zahnrztlichen Praxis. Quintes-

raD, SanzM: Clinical effects of a new mouth-

bution of anaerobic microflora of the tongue to senz-Verlag, Berlin, pp 3950 (2006)

rinse containing chlorhexidine, cetylpyridinium

oral malodor. J Am Dent Assoc 126: 13841393

SeemannR, Duarte da Conceicao, FilippiA, Green- chloride and zinc-lactate on oral halitosis. A

(1995)

manJ, LentonP, NachnaniS, QuirynenM, Rol dual-center, double-blind placebo-controlled

DelangheG, BolenC, DesloovereC: Halitosis dnS, SchulzeH, TangermanA, WinkelEG, Yae- study. J Clin Periodontol 30: 300306 (2003)

Foetor ex ore (in German). Laryngorhinootolo- gakiK, RosenbergM: Halitosis management by

YaegakiK, CiolJM: Examination, classification

gie 78: 521524 (1999) the general dental practitioner results of an

and treatment of halitosis; clinical perspectives.

International Consensus Workshop. Swiss Dent

GreenmanJ, LentonP, SeemannR, NachnaniS: JCan Dent Assoc 66: 257261 (2000)

J124: 12051211 (2014)

Organoleptic assessment of halitosis for dental

YaegakiK, BrunetteDM, TangermanA, ChoeYS,

professionals general recommendations. SlotDE, De GeestS, van der WeijdenFA, Quiry-

WinkelEG, ItoS, KitanoT, IiH, CalenicB, Ishki

JBreath Res 8: 017102 (2014) nenM: Treatment of oral malodour. Medium-

tievN, ImaiT: Standardization of clinical proto-

term efficacy of mechanical and/or chemical

LalemanI, DadamioJ, De GeestS, DekeyserC, Qui- cols in oral malodor research. J Breath Res 6:

agents: a systematic review. J Clin Periodontol

rynenM: Instrumental assessment of halitosis 017101 (2012)

42 Suppl 16: 303316 (2015)

for the general dental practitioner. J Breath

Res8: 017103 (2014)

SWISS DENTAL JOURNAL SSO VOL 126 9 2016

P

You might also like

- Activation of mTOR: A Culprit of Alzheimer's Disease?: Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment DoveDocument16 pagesActivation of mTOR: A Culprit of Alzheimer's Disease?: Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment Dovemr dexterNo ratings yet

- Ulkus Kornea Eng VerDocument15 pagesUlkus Kornea Eng VerDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- Benefits and Risks of Antiretroviral TherapyDocument12 pagesBenefits and Risks of Antiretroviral TherapyAtgy Dhita AnggraeniNo ratings yet

- Medi 96 E5795 PDFDocument5 pagesMedi 96 E5795 PDFDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- Childhood IQ and Bipolar Link PDFDocument9 pagesChildhood IQ and Bipolar Link PDFDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- Nejmoa1514762 PDFDocument12 pagesNejmoa1514762 PDFDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- Pamj 24 182 PDFDocument5 pagesPamj 24 182 PDFDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Anak RirinDocument10 pagesJurnal Anak RirinDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- PRM2016 1658172 PDFDocument7 pagesPRM2016 1658172 PDFDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- Nejmoa1606356 PDFDocument10 pagesNejmoa1606356 PDFDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- The Seven Cardinal MovementsDocument4 pagesThe Seven Cardinal MovementsDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Anak Ririn PDFDocument10 pagesJurnal Anak Ririn PDFDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- 1830 PDF PDFDocument5 pages1830 PDF PDFDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- QuestionsDocument1 pageQuestionsDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- Referat Obgyn FixDocument29 pagesReferat Obgyn FixDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- Clinical Guidelines Acute Rehab Management 2010 InteractiveDocument172 pagesClinical Guidelines Acute Rehab Management 2010 InteractivenathanaelandryNo ratings yet

- The Seven Cardinal MovementsDocument4 pagesThe Seven Cardinal MovementsDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- Fix ObgynDocument17 pagesFix ObgynDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- Unchallengeable Miracles of QuranDocument430 pagesUnchallengeable Miracles of QuranyoursincerefriendNo ratings yet

- Rincian Jadwal Jaga Koas Obsgin 2016 Senin Selas A Rabu Kami S Jumat Sabtu Mingg UDocument1 pageRincian Jadwal Jaga Koas Obsgin 2016 Senin Selas A Rabu Kami S Jumat Sabtu Mingg UDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- Mood Dynamics in Bipolar Disorder: Research Open AccessDocument9 pagesMood Dynamics in Bipolar Disorder: Research Open AccesswulanfarichahNo ratings yet

- Referat Obgyn FixDocument29 pagesReferat Obgyn FixDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- Childhood IQ and Bipolar Link PDFDocument9 pagesChildhood IQ and Bipolar Link PDFDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- 10 4103@0378-6323 116725 PDFDocument14 pages10 4103@0378-6323 116725 PDFDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- The Seven Cardinal MovementsDocument3 pagesThe Seven Cardinal MovementsMaria Mandid0% (1)

- Jurnal Elderly 2 PDFDocument3 pagesJurnal Elderly 2 PDFDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- Pruritus: An Updated Look at An Old ProblemDocument7 pagesPruritus: An Updated Look at An Old ProblemThariq Mubaraq DrcNo ratings yet

- Geriatric Itch PDFDocument16 pagesGeriatric Itch PDFDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- TSWJ2015 803752 PDFDocument8 pagesTSWJ2015 803752 PDFDexter BluesNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Mapping Abap XML PDFDocument88 pagesMapping Abap XML PDFassane2mcsNo ratings yet

- TOS in PRE-CALCULUSDocument2 pagesTOS in PRE-CALCULUSSerjohnRapsingNo ratings yet

- Brahma 152 192sm CM MMDocument6 pagesBrahma 152 192sm CM MMThiago FernandesNo ratings yet

- Clustering Methods for Data MiningDocument60 pagesClustering Methods for Data MiningSuchithra SalilanNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2Document6 pagesAssignment 2Umar ZahidNo ratings yet

- Focal Points: Basic Optics, Chapter 4Document47 pagesFocal Points: Basic Optics, Chapter 4PAM ALVARADONo ratings yet

- COP ImprovementDocument3 pagesCOP ImprovementMainak PaulNo ratings yet

- Cube Nets Non-Verbal Reasoning IntroductionDocument6 pagesCube Nets Non-Verbal Reasoning Introductionmirali74No ratings yet

- Ellipse Properties and GraphingDocument24 pagesEllipse Properties and GraphingREBY ARANZONo ratings yet

- Use Jinja2 To Create TemplatesDocument44 pagesUse Jinja2 To Create TemplatesmNo ratings yet

- Foundations On Friction Creep Piles in Soft ClaysDocument11 pagesFoundations On Friction Creep Piles in Soft ClaysGhaith M. SalihNo ratings yet

- Equipment DetailsDocument10 pagesEquipment Detailsimranjani.skNo ratings yet

- Basic Concepts: ProbabilityDocument32 pagesBasic Concepts: ProbabilityJhedzle Manuel BuenaluzNo ratings yet

- Recent Developments in Ultrasonic NDT Modelling in CIVADocument7 pagesRecent Developments in Ultrasonic NDT Modelling in CIVAcal2_uniNo ratings yet

- Hikmayanto Hartawan PurchDocument12 pagesHikmayanto Hartawan PurchelinNo ratings yet

- DMTH505 Measure Theorey and Functional Analysis PDFDocument349 pagesDMTH505 Measure Theorey and Functional Analysis PDFJahir Uddin LaskarNo ratings yet

- Innovative Lesson PlanDocument12 pagesInnovative Lesson PlanMurali Sambhu33% (3)

- Components of A BarrageDocument21 pagesComponents of A BarrageEngr.Hamid Ismail CheemaNo ratings yet

- Java Array, Inheritance, Exception Handling Interview QuestionsDocument14 pagesJava Array, Inheritance, Exception Handling Interview QuestionsMuthumanikandan Hariraman0% (1)

- An Overview On Reliability, Availability, Maintainability and Supportability (RAMS) EngineeringDocument15 pagesAn Overview On Reliability, Availability, Maintainability and Supportability (RAMS) EngineeringKrinta AlisaNo ratings yet

- 913-2174-01 - Ibypass VHD User Guide Version 1.5 - Revh - VanphDocument218 pages913-2174-01 - Ibypass VHD User Guide Version 1.5 - Revh - Vanphpham hai van100% (1)

- Assignment 3Document2 pagesAssignment 3Spring RollsNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Ballistic Impact Performance of Sic Ceramic-Dyneema Fiber Composite MaterialsDocument10 pagesResearch Article: Ballistic Impact Performance of Sic Ceramic-Dyneema Fiber Composite MaterialsBhasker RamagiriNo ratings yet

- Standard Normal Distribution Table PDFDocument1 pageStandard Normal Distribution Table PDFWong Yan LiNo ratings yet

- Justifying The CMM: (Coordinate Measuring Machine)Document6 pagesJustifying The CMM: (Coordinate Measuring Machine)pm089No ratings yet

- CBCS StatisticsDocument79 pagesCBCS StatisticsXING XINGNo ratings yet

- Black HoleDocument2 pagesBlack HoleLouis Fetilo Fabunan0% (1)

- Line Tension and Pole StrengthDocument34 pagesLine Tension and Pole StrengthDon BunNo ratings yet

- More About Generating FunctionDocument11 pagesMore About Generating FunctionThiên LamNo ratings yet

- The Chemistry of Gemstone Colours 2016Document1 pageThe Chemistry of Gemstone Colours 2016Lukau João PedroNo ratings yet