Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Nat Law 2 Cases

Uploaded by

Kenny Mogato0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

136 views4 pagesOriginal Title

Nat Law 2 Cases.docx

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

136 views4 pagesNat Law 2 Cases

Uploaded by

Kenny MogatoCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

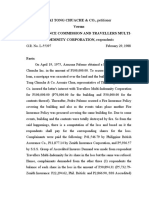

G.R. No.

L-7955 May 30, 1958

JOAQUIN LOPEZ, petitioner,

vs.

ENRIQUE P. OCHOA, respondent.

Ramirez and Ortigas for petitioner.

Jose V. Rosales for respondent.

BAUTISTA ANGELO, J.:

This is a petition for review of a decision of the Court of Appeals modifying that of the court a qou in the sense that "all the

amounts awarded . . . shall be reduced to its equivalent in actual Philippine currency in the proportion of 15 to 1", without

costs.

On August 26, 1943, Enrique P. Ochoa executed in favor of Joaquin Lopez a document whereby he mortgaged a piece of land

located in Manila as security for the payment of a loan in the amount of P15,000 in Japanese military notes to be paid, among

other conditions, as follows:

1.—Devolera dicha cantidad ell el plazo de DOS ANOS, a contar desde la fecha de esta escritura, cuyo plazo se estipula

estrictamente en benificio recproco del el deudor y del acreedor. De tal manera que el deudor no podra pagar al acreedor el

capital ni parte del mismo, antes de la expiracion del plazo, annque ofrezca pagar los intereses correspondientes al periodo no

transcurido de dicho plazo; y de igual manera, el acreedor tampoco podraexigir el pago del capital de este prestamo antes del

plazo convenido. Esta clausula se considera como una condicion especial y esencial de este contrato, que forma parte de su

consideracion especial y de este contrato, que forma parte de su consideracion legal, pues sin ella las partes contratantes no

hubieran aceptado este contrato.

2.—Pagara sobre la mencionada cantidad intereses a razon de cinco por ciento annual, pagaderos por semesestres, vencidos en

la residencia del acreedor del necesiad de requerimento.

On March 1, 1944, Ochoa paid Lopez the sum of P375 as interest on the principal of the aforesaid loan for the period from

August 26, 1943 to February 25, 1944 and on June 12, 1944, he paid P5,000, in Japanese war notes, on account of the principal

for which Lopez issued a receipt.

On August 25, 1944, Ochoa made another payment in the sum of P323.62 on account of interest for the period from February

26, 1944 to August 26, 1944. On October 2, 1944, he tendered to Lopez the payment of the balance of the indebtedness with

the corresponding interest, but the latter refused to accept it on the ground that it was against the terms of the mortgage. In

view of such refusal, Ochoa advised Lopez that he deposit the money in court and, accordingly, he filed a complaint with the

Court of First Instance of Manila accompanied by a deposit in the amount of P10,631.50. Lopez was properly served with

summons on October 7, 1944 but the case was never tried nor its record reconstituted after its destruction during the battle for

the liberation of the City of Manila.

His several demands to cancel the mortgage having failed, Ochoa commenced the present action on January 30, 1950 before

the Court of First Instance of Manila with the prayer that the tender of payment and consignation made by him of the amount

of P10,000 be declared as complete payment of his obligation and that the mortgage executed by him be cancelled, with costs.

Defendant pleaded, that the alleged consignation of the obligation had not been validly made, and set up a counterclaim the

judgment against plaintiff for the mortgage debt of P10,000, still due, together with the stipulated interest and attorneys' fees

and, in default thereof, for the foreclosure of the mortgage in accordance with law.

Finding that the alleged consignation was not valid for it was made when the debt was not yet due and upholding the validity of

the terms of the mortgage contract, the court rendered judgment absolving the defendant of the complaint and sentencing the

plaintiff to pay the sum of P10,000, with interest at the rate of 5 % per annum from January 26, 1650, the further sum of

P2,707.09 as accrued interest, with interest at the legal rate from January 26, 1950, and the sum of 10 % on the principal

amount as attorneys' fees, plus the cost, and ordering plaintiff to make said payment within ninety days, with the warning that,

upon his default, the mortgaged property shall be sold as provided for in the Rules of Court.

The Court of Appeals modified this judgment as stated in the early part of this decision.

After considering the terms of the mortgage contract with regard to the period within which the loan may be paid particularly

the clause to the effect that the debtor shall not pay the capital before the expiration of two years, in the light of the partial

payment made by Ochoa of the sum of P5,000 on account of the principal obligation which Lopez accepted on June 12, 1944,

the Court of Appeals made the following findings:

2.—The acceptance of the partial payment in the sum of P5,000.00 made by the plaintiff-appellant on June 12, 1944 (Exh. "I")

was not a novation of the contract, but it was undoubtedly a waiver by defendant-appellee of the aforesaid term of two years.

It was a relinquished of his right to refuse any payment before the expiration of said term. No explanation having been given

why defendant-appellee received said partial payment before the maturity of the obligation, it may be presumed that his

relinquishment was intentional and his choice to dispense with the term, voluntary. It was not a mere forbearance. (56 Am. Jur.

pp. 102, 104, 107 and 113)

Petitioner now contends that the Court of Appeals erred in considering the acceptance of the partial payment of P5,000 on

account as a waiver of his part of the period of two years for, the reason that suck defense was not set up by respondent in the

court a quo and as such it was error to entertain it to his prejudice. It appears however that in the respondent's reply to

petitioner's answer and counterclaim, the former made the following averment: "defendant herein is now estopped from

claiming that payment of the obligation on the mortgage indebtedness cannot be made before the expiration of two years as

alleged by him in paragraph (5) and sub-paragraph 1 of paragraph (7) of his counterclaim, assuming without admitting that such

alleged stipulation was a condition in the mortgage deed executed between the parties." It may be contended that there is an

allegation of estoppel, and not of waiver, but these two terms are frequently used as convertible. The doctrine of waiver

belongs to the family of, or is based upon, estoppel. This is especially true where the waiver relied upon is constructive or

implied from the conduct of a party, when it is said that the elements of estoppel are attendant.

(2) B. Nature of Doctrine.-The doctrine of waiver has been characterized as technical, as of some arbitrariness. It is one of the

most familiar in the law, prevalent in ancient as well as in modern times throughout every branch of law as well as of practice .

It is a doctrine resting upon an equitable principle which courts of law will recognize, that a person, with full knowledge of the

facts shall not be permitted to act in a manner inconsistent with his former position or conduct to the injury of another, a rule

of judicial policy, the legal outgrowth of judicial abhorrence so to speak, of a person's taking inconsistent positions and gaining

advantages thereby through the aid of courts. The doctrine, it has been said, belongs to the family of, is of the nature of, is

based upon, estoppell. The essence of waiver, it has been stated, is estoppel, and where there is no estoppel, there is no waiver.

"Waiver" and "estoppel" are frequently used as convertible. On the other hand, it has been said that the terms are not

convertible, that an estoppel in pais has connections in no wise akin to waiver, and that the doctrine of waiver does not

necessarily depend on estoppel or misrepresentation; thus, a waiver does not necessarily imply that one has been misled to his

prejudice or into an altered position; a waiver may be created by acts, conduct, or declaration to create a technical estoppel.

However, the distinction, it has been said, is more easily preserved in dealing with express waiver, but where the waiver relied

upon is constructive or merely implied from the conduct of a party, irrespective of what his actual intention may have been, it is

at least questionable if there are not present some of the elements of estoppel. (67 C. J. pp. 294-295. Emphasis supplied.)

Petitioner also, contends that it was error to consider that respondent made a partial payment of P5,000 on account of his

principal obligation there being no proof submitted by him to that effect. But the Court of Appeals found it as a fact that such

partial payment was actually made especially considering the receipt signed by him acknowledging said payment. It being a

question of fact, it cannot now be looked into at this stage of the proceeding.

Another contention refers to the application of the Ballantyne scale of values to the present case on the pretense that the same

has not been set up as a defense nor has evidence to prove it been presented. But this pretense is untenable because said

Ballantyne scale is now a matter that comes with in judicial notice it having been applied by this Court in several previous cases

and had become part of our jurisprudence. There is therefore no cogent reason why it cannot now be considered even if it has

not been set up as a defense.

It is finally contended that the Court of Appeals erred in revaluing the balance of the obligation under the Ballantyne scale of

values taking as basis the month of June, 1944 because, in the opinion of petitioner, the basis should be the date of the

mortgage, or on August 26, 1943. On this point, the court said: "Defendant-appellee having waived, on June 12, 1944, his right

to the term of two years agreed upon in the contract (Exh. "1"), the obligation under consideration became payable since June

13, 1944 and during the Japanese military occupation. Hence, conformably with the ruling of the Supreme Court, it should be

revalued on the basis of the relative value of the Japanese military notes in Philippine genuine currency on June, 1944 under

the Ballantyne sliding scale of values, which is 15 to 1."

There is nothing incorrect in this finding considering that the obligation only became payable on June 13, 1944. This became

possible because of petitioner's waiver. In fact, several attempts were made by respondent to pay the whole obligation

thereabouts but his attempts failed because of petitioner's refusal. It is therefore reasonable that the revaluation be made as of

said date and not on the date of the mortgage.

The decision appealed from being in accordance with law, the same is hereby affirmed, with costs against petitioner.

G.R. No. L-9343 December 29, 1959

MANILA SURETY and FIDELITY CO., INC., plaintiff-appellee,

vs.

VALENTIN R. LIM, defendant-appellant.

De Santos, Herrera and Delfino for appellee.

Carlos, Laurea, Fernando and Padilla for appellant.

ENDENCIA, J.:

This is an appeal from a decision rendered by the Court of First Instance of Manila ordering the defendant Valentin R. Lim to

pay to the plaintiff the sum of P1000 with legal interest from July 26, 1951, with costs. The appeal is predicated on the

proposition that the lower court erred:

1. In holding and ordering appellant to return the sum of P1000 to appellee;

2. In ordering reimbursement merely because the order under which appellee made payment was subsequently set aside and

in failing to rule that reasons of equity entitle appellant tot retain the amount delivered; and

3. In assuming jurisdiction of the action that give rise to the present appeal.

The present case is an offset of the decision rendered by Us on December 29, 1949 in cases G.R. Nos. L-2717, 2718 and 2767 *,

where in we declared that damages suffered by reason of the issuance of a writ or preliminary injunction must be claimed,

ascertained and awarded in the final judgment, and that the damages awarded therein in favor of defendant Valentin R. Lim by

reason of the issuance of the preliminary injunction in civil cases Nos. 487 and 7674 of the Court of First Instance of Rizal, were

granted in violation of Section 9 of Rule 60 in connection with Section 20 of Rule 59 of the Rules of Court, for said damages

were not included in the decision and were awarded long time after it became final and executory.

The factual background of the present case is as follows: On February 26, 1946, in civil case No. 32 of the Justice of the Peace

Court of Pasay, Valentin R. Lim obtained a judgment against Irineo Facundo, "ordering the latter to vacate the premises

described in the complaint and to pay the plaintiff a monthly rental of P100 from February 18, 1955 until the defendant vacate

the premises and to pay the costs." Ireneo Facundo did not appeal from the decision but instead caused the filing of a special

civil action for certiorari and prohibition (Case No. 7674) in the Court of First Instance of Rizal, entitled Ireneo Facundo,

petitioner, vs. Jose M. Santos, ex-Justice of the Peace of Pasay, Ricardo C. Robles, as Justice of the Peace of Pasay, Valentin R.

Lim, respondents, wherein a writ of preliminary injunction was issued upon the filing by Facundo of a in the sum of P1000,

which bond was posted by the Manila Surety & Fidelity Co., Inc. On June 21, 1946, this case was a dismissed by the Court of

First Instance of Rizal and the dismissal was subsequent affirmed on appeal by the Supreme Court on December 17, 1946.

On July 29, 1948, Valentin R. Lim filed with the Court of First Instance of Rizal, in said case No. 7694, a motion for the

determination of damages sustained by him fore uncollected rentals due to the issuance of the above-mentioned writ of

preliminary injunction in said case. Despite the fact that the decision in that case — wherein no damages were awarded to

appellant Lim — had already become final two years more or less from the date of September 30, 1948, allowed appellant to

prove said damages, awarded them and ordered the confiscation of the bond posted by the Manila Surety & Fidelity Co., Inc.

and directed the latter to pay appellant Lim the sum of P1000, which order gave rise to a petition for certiorari filed and

docketed in this Court as G.R. No.

L-2718.

On April 9, 1948, Irineo Facundo filed in the Court of First Instance of Rizal a special civil action for prohibition against Lucio M.

Tinagco as municipal Judge of Rizal City, and Valentin R. Lim, wherein he prayed that a writ of preliminary injunction be issued

upon filing a bond of P1000 to prevent Judge Tinagco from issuing an alias writ of execution in civil case No. 32 of his court.

Upon Facundo's filing of the bond, which was posted by the Manila Surety & Fidelity Co., Inc., the court issued the

corresponding preliminary injunction. On April 24, 1948, the court dismissed this case and dissolved the writ of preliminary

injunction; hence on July 29, 1948, appellant filed a petition with said court asking for damages sustained by him for failure to

collect the rentals because of the issuance of the aforementioned preliminary injunction; and despite the fact that the decision

in civil case No. 487 — wherein no damages were awarded for the issuance of said preliminary injunction — had become final

on May 9, 1948, the Court of First Instance of Rizal allowed the damages sought for, ordered the confiscation of the bond

posted by the Manila Surety & Fidelity Co., Inc., and directed the latter to pay to Lim the full value of said Court, docketed as

G.R. No. L-2712.

Thereafter, or to be more exact, on January 24, 1949, the Court of First Instance of Rizal, issued a writ of execution in the

aforementioned cases Nos. 487 and 7674, directing the Sheriff of Manila to require the Manila Surety 7 Fidelity Co., Inc. to pay

to appellant Valentin R. Lim the sum of P1000 is satisfaction of its liability under the preliminary injunction bond, and in

compliance with the writ of execution, the Manila Surety & Fidelity Co., Inc., herein appellee, delivered to the Sheriff of Manila

the sum of P1,105.01 in full satisfaction of the writ of execution and the fees of the Sheriff, of which amount the sum of P1000

was delivered by the Sheriff to appellant Valentin R. Lim.

On December 29, 1949, we declared that the writs of execution issued in civil cases Nos. 487 and 7674 of the Court of First

Instance were null and void, and on January 21, 1951, the herein plaintiff-appellee demanded from the defendant-appellant the

immediate reimbursement of the payment it made in compliance with said writs, but the herein defendant-appellant refused

to re turn the above-mentioned amount of P1,105.01, hence plaintiff-appellee initiated the present action.

The main contention of defendant-appellant is: that plaintiff-appellee has paid voluntarily its natural obligation and therefore is

precluded from recovering that which was delivered to defendant-appellant, and that the requisites of solutio indebti which is

the only basis for the return of the amount paid do not exist in the present case. Appellant invokes the following provisions of

the Civil Code:

ART. 1423. Natural obligations, not being based on positive law but on equity and natural law, do not grant a right of action to

enforce their performance, but after voluntary fulfillment by the obligor, they authorize the retention of what has been

delivered or rendered by reason thereof.

ART. 1424. When a right to sue upon a civil obligation has lapsed be extensive prescription, the obligor who voluntarily

performs the contract cannot recover what he has delivered or the value of the service he has rendered.

ART. 1428. When, after an action to enforce a civil obligations has failed, the defendant voluntarily performs the obligation he

cannot demand the return of what he has delivered or the payment of the value of the service he has rendered.

Upon careful examination of the foregoing provisions of law and undisputed facts of the case, we find appellants contention to

be untenable, for the payment made by the herein plaintiff-appellee to defendant-appellant was not voluntary, it was thru a

coercive process of the writ of execution issued at the instant and insistence of the defendant-appellant. Certainly, were it not

for said writ of execution, plaintiff-appellee would not have paid to defendant-appellant the amount in question. It should be

noted that at the time the said writ of execution was issued, the right of defendant-appellant to damages caused unto him by

reason of his inability to collect the rents of the property involved in civil cases Nos. 487 and 7674, was still pending

determination by the Supreme Court, and had defendant-appellant waited for the final decision of the Supreme Court on said

damages, surely he would not have caused the issuance of the writ of execution in said civil cases and thus compel plaintiff-

appellee to pay to him the aforementioned sum of P1,105.01.lawphi1.net

It is contended be defendant-appellant that there is not justification for ordering the return of the amount n question as the

court below did, for in the present case, the requisites of solutio indebti do not exist. But the instant case does not fall under

the provisions of Article 2154; it is based on the theory that the judgment upon which the plaintiff-appellee made payment was

declared null and void and consequently the execution of said judgment and the payment made thereunder were also null and

void. It is quite a settled rule that damages caused by the issuance of a preliminary injunction should be adjudicated in the final

judgment rendered in the case in which the injunction was issued. In civil cases Nos. 487 and 7674 of the Court of First Instance

of Rizal, the award of damages was done after the decision on the merit of said cases became final, so said award was illegal,

for which no writ of execution could be validly issued. Evidently, the order of September 30, 1949 of the Court of First Instance

of Rizal whereby it awarded damages and ordered the forfeiture and execution of plaintiff's bond in each of said two cases, is

null and void, it having been issued in violation of the Rules of Court.

Defendant-appellant lastly raises the question of jurisdiction of the court below, claiming that the present action should have

been filed with the Court of First Instance of Rizal and citing as follows:

A court which takes cognizance of an action over which it has jurisdiction and power to afford complete relief has the exclusive

right to dispose of the controversy without interference from other courts of concurrent jurisdiction in which similar actions are

subsequently instituted between the same parties seeking similar remedies and involving the same questions. (21 C.J.S. 745).

(Emphasis supplied)

. . . every court has the inherent power, for the advancement of justice, to correct errors of its ministerial officers, and to

control its own process. (Dimayuga vs. Raymundo, et al., 76 Phil., 143.).

Independent of any statutory provision, we assert that every court has inherent power to do all things reasonably necessary for

the administration of justice within the scope of its jurisdiction. (Shioji vs. Harvey, 43 Phil., 333.)

Appellant's contention is untenable. The present action is for a sum of money and all the parties involved are residents of the

City of Manila as averred in paragraph 1 of the complaint. Under Sec. 1 of Rule 5 of the Rules of Court, civil actions like the one

in question may be commenced and tried where the defendant or any of the defendants resides or may be found or where the

plaintiff or any of the plaintiffs resides, at the election of the plaintiff.

Wherefore, finding no error in the decision appealed from the same is hereby affirmed, with costs.

GR No. L-47362 December 19, 1940JOHN F. VILLARROEL, appellant-appellant,vs. B ERNARD

IN

O

ESTRADA, turned-appellee.

D. Felipe Agoncillo in representation of the appellant-appelante.D. Crispin Oben in representation of the defendant-appellee.

DECISION

Avanceña,J.:

On May 9, 1912, Alejandro F. Callao, mother of defendant John F. Villarroel, obtained from thespousesMariano Estrada and Severina a loan of P1, 000 payable

after seven years (ExhibitoA). Alejandra died,leaving as sole heir to the defendant.Spouses Mariano Estrada and Severina alsodied, leaving as soleheir to the

plaintiff Bernardino Estrada. On August 9, 1930, the defendant signeda document (Exhibito B) bywhich the applicant must declare in the amount of P1, 000,

with aninterest of 12 percent per year. Thisaction relates to the recovery of this amount.The Court of First Instance of Laguna, which was filed in this action,

condemn the defendant to paytheclaimed amount of P1, 000 with legal interest of 12 percent per year since the August 9, 1930until full pay.He appealed the

sentence.It will be noted that the parties in the present case are, respectively, the only heirs and creditors of theoriginal debtor. This action is brought under the

defendant's liability as the only son of the originaldebtor infavor of the plaintiff contracted, sole heir of primitive loa creditors. It is recognized that theamount of

P1, 000to which contracts this obligation is the same debt of the mother's parents sued theplaintiff. Although the action to recover the original

debt has prescribed and when the lawsuit was filed in thiscase,the question raised in this appeal is primarily whether, notwithstanding such

requirement, theaction taken isappropriate. However, this action is based on the original obligation contracted by themother of thedefendant, who has already

prescribed, but in which the defendant contracted theAugust 9, 1930 (ExhibitoB) by assuming the fulfillment of that obligation, as prescribed. Being theonly

defendant in the originalherdero debtor eligible successor into his inheritance, that debt broughtby his mother in law, although it lostits effectiveness by

prescription, is now, however, for a moralobligation, that is consideration enough tocreate and make effective and enforceable obligationvoluntarily contracted

its August 9, 1930 in Exhibito B.The rule that a new promise to pay a debt prrescrita must be made by the same person obligatedorotherwise legally authorized

by it, is not applicable to the present case is not required in compliancewiththe mandatory obligation orignalmente but which would give it voluntarily assumed

thisobligation.It confirmsthe judgment appealed from, with costs against the appellant. IT IS SO ORDERED.

You might also like

- Country Bankers Insurance vs. CA, GR. 85161, Sept 9, 1991Document4 pagesCountry Bankers Insurance vs. CA, GR. 85161, Sept 9, 1991Fides DamascoNo ratings yet

- Gaisano V Insurance G.R. No. 147839 June 8, 2006Document3 pagesGaisano V Insurance G.R. No. 147839 June 8, 2006Bay Nald LaraNo ratings yet

- McCullough v. Berger, 43 Phil 823, September 26, 1922Document2 pagesMcCullough v. Berger, 43 Phil 823, September 26, 1922Gabriel Hernandez100% (1)

- Case 1 and 2 (Transf)Document4 pagesCase 1 and 2 (Transf)11 LamenNo ratings yet

- Lapitan v. Scandia (Nature of Coa Rescission)Document3 pagesLapitan v. Scandia (Nature of Coa Rescission)alyssa_castillo_20No ratings yet

- 241 - Shrimp Specialist, Inc. v. Fuji-Triumph, 7 December 2009Document2 pages241 - Shrimp Specialist, Inc. v. Fuji-Triumph, 7 December 2009Reynaldo Lepatan Jr.No ratings yet

- 207747Document7 pages207747puditz21No ratings yet

- Book Iii Title V. - Prescription: Eneral Rovisions Hat Is PrescriptionDocument166 pagesBook Iii Title V. - Prescription: Eneral Rovisions Hat Is PrescriptionJerick BartolataNo ratings yet

- Case 12Document3 pagesCase 12April CaringalNo ratings yet

- Case Digests Finals 1Document6 pagesCase Digests Finals 1Mary BalojaNo ratings yet

- Notes Obliiiiiiiiiiiii WordDocument54 pagesNotes Obliiiiiiiiiiiii Wordgeni_pearlcNo ratings yet

- Yulo vs. People of The PhilippinesDocument2 pagesYulo vs. People of The PhilippinesLake GuevarraNo ratings yet

- DEL CARMEN v. SPS. SABORDODocument3 pagesDEL CARMEN v. SPS. SABORDOMac SorianoNo ratings yet

- Moran V CA - GR L-59956 - Oct 31 1984Document9 pagesMoran V CA - GR L-59956 - Oct 31 1984Jeremiah ReynaldoNo ratings yet

- INTERNATIONAL CORPORATE BANK V GUECODocument3 pagesINTERNATIONAL CORPORATE BANK V GUECOAnonymous aoDkpVbRENo ratings yet

- 9 Francisco V HerreraDocument1 page9 Francisco V HerreraJulius ManaloNo ratings yet

- Tang Vs CA and PhilamlifeDocument1 pageTang Vs CA and PhilamlifeAngelic ArcherNo ratings yet

- Federation of United NAMARCO Distributors vs. CA 4 SCRA 867Document11 pagesFederation of United NAMARCO Distributors vs. CA 4 SCRA 867Czarina CidNo ratings yet

- Oblicon NotesDocument13 pagesOblicon NotesLovelyNo ratings yet

- MODULE DWCC - Obligation and Contracts Part1 OnlineDocument17 pagesMODULE DWCC - Obligation and Contracts Part1 OnlineCharice Anne VillamarinNo ratings yet

- Jaravata v. SandiganbayanDocument1 pageJaravata v. SandiganbayanJenell CruzNo ratings yet

- The Role of Accountants in Nation Building Through TaxationDocument2 pagesThe Role of Accountants in Nation Building Through TaxationJoshua Ryan CanatuanNo ratings yet

- BPI Vs Concepcion HijosDocument2 pagesBPI Vs Concepcion HijosJessa Mary Ann CedeñoNo ratings yet

- 79 NFF Industrial Corporation vs. G & L Associated BrokerageDocument1 page79 NFF Industrial Corporation vs. G & L Associated BrokerageJemNo ratings yet

- Case Study 10Document2 pagesCase Study 10teodoro labangco100% (1)

- Property LAw Arts 1390 - 1402Document5 pagesProperty LAw Arts 1390 - 1402Onat PNo ratings yet

- Cui V Arellano UniversityDocument1 pageCui V Arellano UniversityMiguel C. NunezNo ratings yet

- Negotiable Instruments Law Digests Section 1Document13 pagesNegotiable Instruments Law Digests Section 1Jay-ar Rivera BadulisNo ratings yet

- De LeonDocument6 pagesDe Leoncristina seguinNo ratings yet

- Hernaez vs. de Los AngelesDocument1 pageHernaez vs. de Los AngelesRaymundNo ratings yet

- Case Digest No. 4Document48 pagesCase Digest No. 4Sherwind Mon TeNo ratings yet

- 2.1 - Bachrach vs. GolingcoDocument3 pages2.1 - Bachrach vs. GolingcoElaine Atienza-IllescasNo ratings yet

- Module 1 - Topic No. 1 - Part9Document10 pagesModule 1 - Topic No. 1 - Part9Limuel MacasaetNo ratings yet

- Payment or Performance (Autosaved)Document14 pagesPayment or Performance (Autosaved)Amie Jane MirandaNo ratings yet

- Aguirre vs. People - DigestDocument2 pagesAguirre vs. People - DigestMaria Jennifer Yumul BorbonNo ratings yet

- MODULE DWCC - Obligation and Contracts Part2 OnlineDocument15 pagesMODULE DWCC - Obligation and Contracts Part2 OnlineCharice Anne VillamarinNo ratings yet

- Sir PapsDocument15 pagesSir PapsRey Niño GarciaNo ratings yet

- Notes For Midterm ObliConDocument8 pagesNotes For Midterm ObliConmichelle_calzada_1No ratings yet

- First United Constructors Corporation and Blue Star Construction Corporation, Petitioners, V. Bayanihan Automotive Corporation, Respondent.Document7 pagesFirst United Constructors Corporation and Blue Star Construction Corporation, Petitioners, V. Bayanihan Automotive Corporation, Respondent.dteroseNo ratings yet

- NovDocument47 pagesNovNeb GarcNo ratings yet

- Edgardo E. Mendoza v. Abundio Z. ArrietaDocument1 pageEdgardo E. Mendoza v. Abundio Z. ArrietaCharLene MaRieNo ratings yet

- (G.R. No. 171428) Article (1338-1344)Document4 pages(G.R. No. 171428) Article (1338-1344)Marjorie G. EscuadroNo ratings yet

- People of The Philippines v. Dionaldo (2015)Document3 pagesPeople of The Philippines v. Dionaldo (2015)Gamar AlihNo ratings yet

- Metro Concast Steel Corporation vs. Allied Bank CorporationDocument13 pagesMetro Concast Steel Corporation vs. Allied Bank CorporationGab CarasigNo ratings yet

- HEIRS OF ARTURO REYES v. ELENA SOCCO-BELTRANDocument3 pagesHEIRS OF ARTURO REYES v. ELENA SOCCO-BELTRANRhodz Coyoca EmbalsadoNo ratings yet

- February 6, 2013 Winnieclaire: Posted On byDocument9 pagesFebruary 6, 2013 Winnieclaire: Posted On bySam LagoNo ratings yet

- SalesDocument2 pagesSalesAbegail DalanaoNo ratings yet

- GR 76189Document1 pageGR 76189manolaytolayNo ratings yet

- Effects of Fortuitous Events in ObligationsDocument33 pagesEffects of Fortuitous Events in ObligationsMishel EscañoNo ratings yet

- Obli - Olegario Vs CADocument3 pagesObli - Olegario Vs CASyrine MallorcaNo ratings yet

- Law 1 Fourth Exam UM-1Document2 pagesLaw 1 Fourth Exam UM-1PatoyNo ratings yet

- STS Lecture 6 Science Education in The PhilippinesDocument43 pagesSTS Lecture 6 Science Education in The PhilippinesTeaNo ratings yet

- Pryce V PAGCOR 2 Florentino V SupervalueDocument2 pagesPryce V PAGCOR 2 Florentino V SupervalueHazel NatanauanNo ratings yet

- VICENTE SABALVARO Vs GalingerDocument4 pagesVICENTE SABALVARO Vs GalingershepimentelNo ratings yet

- Siquian v. People, 171 SCRA 223Document5 pagesSiquian v. People, 171 SCRA 223PRINCESS MAGPATOCNo ratings yet

- Ong Chua Vs Carr 53 PhilDocument1 pageOng Chua Vs Carr 53 PhilayenNo ratings yet

- Current - Liabilities - PPTX Filename UTF-8''Current LiabilitiesDocument44 pagesCurrent - Liabilities - PPTX Filename UTF-8''Current LiabilitieskristineNo ratings yet

- SoftDocument2 pagesSoftAnonymous WmvilCEFNo ratings yet

- Civil Law Review 2 CasesDocument88 pagesCivil Law Review 2 CasesDan_Pelagio_5466No ratings yet

- Land CasesDocument33 pagesLand CasesPauline MaeNo ratings yet

- Flowers For The Devil - A Dark V - Vlad KahanyDocument435 pagesFlowers For The Devil - A Dark V - Vlad KahanyFizzah Sardar100% (6)

- A Natural Disaster Story: World Scout Environment BadgeDocument4 pagesA Natural Disaster Story: World Scout Environment BadgeMurali Krishna TNo ratings yet

- Đề ôn thi giữa kì IDocument7 pagesĐề ôn thi giữa kì Ikhanhlinhh68No ratings yet

- C++ & Object Oriented Programming: Dr. Alekha Kumar MishraDocument23 pagesC++ & Object Oriented Programming: Dr. Alekha Kumar MishraPriyanshu Kumar KeshriNo ratings yet

- Ageing Baby BoomersDocument118 pagesAgeing Baby Boomersstephloh100% (1)

- 02 Clemente V CADocument8 pages02 Clemente V CAATRNo ratings yet

- M.Vikram: Department of Electronics and Communication EngineeringDocument26 pagesM.Vikram: Department of Electronics and Communication EngineeringSyed AmaanNo ratings yet

- Gann Trding PDFDocument9 pagesGann Trding PDFMayur KasarNo ratings yet

- Determination of Distribution Coefficient of Iodine Between Two Immiscible SolventsDocument6 pagesDetermination of Distribution Coefficient of Iodine Between Two Immiscible SolventsRafid Jawad100% (1)

- Physiotherapy TamDocument343 pagesPhysiotherapy TamHAYVANIMSI TVNo ratings yet

- 2 BA British and American Life and InstitutionsDocument3 pages2 BA British and American Life and Institutionsguest1957No ratings yet

- Standard Operating Procedures in Drafting July1Document21 pagesStandard Operating Procedures in Drafting July1Edel VilladolidNo ratings yet

- Senarai Akta A MalaysiaDocument8 pagesSenarai Akta A MalaysiawswmadihiNo ratings yet

- Note 1-Estate Under AdministrationDocument8 pagesNote 1-Estate Under AdministrationNur Dina AbsbNo ratings yet

- My Slow Carb Diet Experience, Hacking With Four Hour BodyDocument37 pagesMy Slow Carb Diet Experience, Hacking With Four Hour BodyJason A. Nunnelley100% (2)

- Fiber Optic Color ChartDocument1 pageFiber Optic Color Charttohamy2009100% (2)

- IdentifyDocument40 pagesIdentifyLeonard Kenshin LianzaNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument44 pagesUntitledDhvani PanchalNo ratings yet

- What Got You Here Won't Get You ThereDocument4 pagesWhat Got You Here Won't Get You ThereAbdi50% (6)

- State Bank of India: Re Cruitme NT of Clerical StaffDocument3 pagesState Bank of India: Re Cruitme NT of Clerical StaffthulasiramaswamyNo ratings yet

- Cost Study On SHEET-FED PRESS OPERATIONSDocument525 pagesCost Study On SHEET-FED PRESS OPERATIONSalexbilchuk100% (1)

- PW 1987 01 PDFDocument80 pagesPW 1987 01 PDFEugenio Martin CuencaNo ratings yet

- Java Programming - Module2021Document10 pagesJava Programming - Module2021steven hernandezNo ratings yet

- Bank TaglineDocument2 pagesBank TaglineSathish BabuNo ratings yet

- 100 Golden Rules of English Grammar For Error Detection and Sentence Improvement - SSC CGL GuideDocument16 pages100 Golden Rules of English Grammar For Error Detection and Sentence Improvement - SSC CGL GuideAkshay MishraNo ratings yet

- Nano Technology Oil RefiningDocument19 pagesNano Technology Oil RefiningNikunj Agrawal100% (1)

- Withholding Tax LatestDocument138 pagesWithholding Tax LatestJayson Jay JardineroNo ratings yet

- Hampers 2023 - Updted Back Cover - FADocument20 pagesHampers 2023 - Updted Back Cover - FAHaris HaryadiNo ratings yet

- Elec Final OutputDocument3 pagesElec Final Outputluebert kunNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting The Success or Failure of Project Management Methodologies (PMM) Usage in The UK and Nigerian Construction IndustryDocument12 pagesFactors Affecting The Success or Failure of Project Management Methodologies (PMM) Usage in The UK and Nigerian Construction IndustryGeorge PereiraNo ratings yet