Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lymphocyte Subset and Cellular Immune

Uploaded by

SoulyogaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Lymphocyte Subset and Cellular Immune

Uploaded by

SoulyogaCopyright:

Available Formats

RAPID COMMUNICATION

Lymphocyte Subset and Cellular Immune Responses to a Brief

Experimental Stressor

ELIZABETH A. BACHEN, MA, STEPHEN B. MANUCK, PHD,

ANNA L. MARSLAND, RGN, BSC, SHELDON COHEN, PHD,

SUSAN B. MALKOFF, MS, MATTHEW F. MULDOON, MD, AND

BRUCE S. RABIN, MD, PHD

To evaluate effects of acute mental stress on aspects of cellular immunity, lymphocyte

populations and phytohemagglutinin (PHA)-stimulated T-cell mitogenesis were measured in

33 healthy young men, both before and immediately following subjects performance of a

frustrating, 21-minute laboratory task (Stroop test). Relative to baseline evaluations, post-task

measurements showed a significant reduction in mitogenesis and alterations in various circu-

lating lymphocyte populations; the latter included a diminished T-helper/T-suppressor cell

ratio and an elevation in the number of natural killer cells. Eleven subjects assigned to a

control (unstressed) condition exhibited no changes in lymphocyte populations, but did show

an increase in T-cell proliferation, compared with pretask measurements.

Key words: experimental stress; psychoimmunology; cellular immunity; mitogenesis; lympho-

cytes; natural killer cells.

INTRODUCTION interpretation of these studies is limited

by their correlational design. Although

While a number of investigations have few studies have examined immunologic

demonstrated associations between natu-

rally occurring stressors and alterations in changes to acute psychological stressors

cellular immune function (e.g., 1-6), within controlled laboratory settings,

there is some experimental evidence that

mental stress similarly alters both quan-

titative and qualitative aspects of cellular

From the Department of Psychology, University immunity in human-beings, as indicated

of Pittsburgh (E.A.B., S.B.M., A.L.M., S.B.M.); the by alterations in peripheral T-suppressor/

Department of Psychology, Carnegie Mellon Univer-

sity (S.C.); and the Center for Clinical Pharmacology cytotoxic and natural killer cell popula-

(M.F.M.) and Department of Pathology (B.S.R.), Uni- tions (7-10), and by a decreased ability of

versity of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, T lymphocytes to divide when incubated

Pennsylvania.

Address reprint requests to: Elizabeth A. Bachen,

with a nonspecific mitotic stimulant (7).

M.A., Behavioral Physiology Laboratory, 506 Old In this report, we attempt to replicate,

Engineering Hall, 4015 O'Hara Street, University of within a single experimental protocol,

Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15260.

Received for publication May 15, 1992; revision

these observations regarding the effects of

received July 30. 1992 acute stress on circulating lymphocyte

Psychosomatic Medicine 54:673-679 (1992) 673

0033-3174/92/5406-0673S03 00/0

Copyright © 1992 by the American Psychos*

E. A. BACHEN et al.

populations and the T-mitogenic re- voice synthesis. HR and BP were recorded every 4

sponses of healthy young adults. minutes during task performance and a second 30

ml of blood was collected immediately after this

period.

METHODS

Subjects Immune Assays

Forty-four undergraduate males (aged 19-25 A common measure of cellular immune function

years) were randomly assigned in a ratio of 3:1 to is the ability of the T (thymus-derived) lymphocytes

either a stress or control condition. In the stress to proliferate, in vitro, in response to nonspecific

condition, in vitro measurements of cellular im- mitogens. Extent of mitotic division may, in turn,

mune function were obtained before and after sub- reflect the interrelation between two different pop-

jects were administered a distinctly frustrating lab- ulations of lymphocytes—T-helper lymphocytes

oratory stressor. Heart rate (HR) and blood pressure (denoted CD4 cells) whose role is to facilitate im-

(BP) were also assessed at baseline and during sub- mune response, and T-suppressor/cytotoxic lym-

jects' task performance. The same measurements phocytes (CD8 cells), which act, in part, to suppress

were obtained in the control condition, although immune response. In this study, we examined effects

these subjects were not exposed to the experimental of the experimental stressor on T-mitogenic re-

stressor. All subjects gave informed consent to par- sponses and on circulating lymphocyte populations.

ticipate in this investigation, which was approved To assess nonspecific mitogen stimulation, a

by the Biomedical 1RB of the University of Pitts- whole blood assay was conducted to establish a dose

burgh. response curve at phytohemagglutinin (PHA) con-

centrations of 0.5. 2.5, 5.0,10.0. and 20.0 Mg/ml.1 The

difference in counts per minute between stimulated

and unstimulated samples was determined sepa-

Procedures rately for each concentration; these values were

subjected to logarithmic (base 10) transformation

Subjects abstained from food and caffeine for 12

prior to statistical evaluation.

hours before attending a laboratory session begin-

ning at 08:30 A.M. Upon arrival at the laboratory, a Circulating populations of T-cell subtypes, B-cells

nurse inserted an intravenous catheter into a vein and natural killer (NK) cells were assessed in whole

in the antecubital fossa of the subject's dominant blood using flow cytometry. Lymphocyte subsets

arm. The catheter was connected to an exfusion were analyzed using monoclonal antibodies labeled

pump via a short length of heparinized, SILASTIC® with either fluorescein or phycoerythrin to quantify

tubing (Dow Corning, Midland, Michigan). Follow- CD3 (total T-cells), CD4 (T-helper cells), CD8 (T-

ing venipuncture, an occluding cuff was placed on suppressor/cytotoxic cells), CD19 (B-cells), and NK

the subject's nondominant arm and connected to a

vital signs monitor (Critikon Dinamap 8100) for au-

tomated measurement of HR (in beats per minute

(bpm)) and systolic and diastolic blood pressure (in 1

mm Hg). Following instrumentation, the subject Blood was diluted 1:10 with RPMI-1640 tissue

rested for 30 minutes to achieve baseline conditions. culture medium, supplemented with 10 HIM Hepes,

During the last 6 minutes of this period. HR and BP 2 mM glutamine, and 50 Mg gentamicin per ml. One

(two readings) were recorded, and 30 ml of blood hundred microliters of diluted blood was added to a

was drawn. At this point, the control subjects were 96-well, flat-bottomed culture plate (Costar #3596)

instructed to continue to sit quietly for 21 minutes, containing 100 ^il of mitogen solution added in quad-

while the stress group performed a 21-minute com- ruplicate (100 MI) of PHA prepared in RPMI-1640 to

puterized version of the Stroop Color-Word Interfer- yield the five final PHA concentrations. The plates

ence Test (11). Subjects indicated their responses by were incubated for 120 hours at 37°C in air and 5%

pressing one of four microswitches on a keypad CO2. Eighteen hours before the end of incubation,

under pressure of time and against a distractor (ran- the wells were pulsed with 1 mCi tritiated thymi-

dom test responses) generated by computerized dine and harvested for counting.

674 Psychosomatic Medicine 54:673-679 (1992)

CELLULAR IMMUNE RESPONSE

cells." Response was defined as the baseline-to-task = 35.79, p < 0.0001), systolic and diastolic

change in both the number of cells of each type and blood pressure, (F(l,42) = 49.74, p <

the ratio of CD4 to CDS cell subtypes. Numbers of

NK cells could not be computed for one subject due 0.0001; F(l,42) = 23.04, p < 0.0001). In

to clotting, and the T-mitogenic responses of four each instance, task values were signifi-

subjects could not be determined due to bacterial cantly higher than baseline measure-

contamination ments among stressed subjects, but did

not differ from baseline in controls.

Among stressed subjects, mean baseline-

to-task changes in HR were +13 bpm, and

Statistical Analysis for systolic and diastolic blood pressure,

Prior to statistical analysis, HR and BP data were +15 and +12 mm Hg, respectively; control

reduced by calculating mean values for both base-

lino and experimental periods. These values, as well subjects showed a corresponding HR in-

as the lymphocyte subset data, were subjected to 2 crease of 1 bpm, and no changes in BP.

x 2 (Groups,r,,ss.Co,,irni) x (Periodba,eimo.insk) repeated With respect to immune parameters,

measures analysis of variance (ANOVAs), to evalu- the ANOVA for T-cell mitogenic re-

ate changes that may have occurred in response to

the experimental stressor. T-cell mitogenic re- sponses revealed a significant Group X

sponses were similarly analyzed by a 2 x 2 x 5 Period interaction (F(l,38) = 10.04, p <

(Group.slross„„„„,,) X (Periodbn,oi,n« ...sk) x (PHA Concen- 0.05).3 Comparisons among means

tration(os, ^5, .in. IOO. son w/mi) repeated measures AN- showed that T-cell mitogenesis decreased

OVA. It was predicted that a significant Group X significantly from pretask to post-task

Period interaction would emerge in each ANOVA,

and that for each dependent measure, the stressed measurements in the stressed subjects,

subjects would show a change in the level of the and increased significantly among con-

dependent variable during or following task per- trols (means and standard deviations are

formance, relative to corresponding pretask (base- presented in Table 1). The absence of a

line) measurements; it was expected that control

subjects would show either no change or a change

Group X Period X Concentration interac-

in the opposite direction. A priori comparisons tion indicates that these relationships

among means were performed using t tests (alpha generalized across all five PHA concentra-

level = 0.05). tions. Similarly, analysis of lymphocyte

subpopulations showed a significant

Group x Period interaction for the T-

helper/suppressor (CD4:CD8) ratio

RESULTS (F(l,42) = 9.08, p < 0,005)). Here, there

Task-related changes in heart rate and was a significant decline in the CD4:CD8

blood pressure were evaluated first, as an ratio from baseline to post-task measure-

index of the physiologic effect of the ex-

perimental stressor independent of im-

mune parameters. These analyses re-

3

vealed a significant Group X Period inter- This analysis also yielded a significant main

action of all three measures: HR (F(l,42) effect for PHA concentration (F(4,152) = 4.52, p <

0.0001), reflecting expected differences in cell divi-

sion to the graded concentration of mitogen. Average

counts per minute (log10). collapsed across baseline

and experimental period measurements, were 5.84

1

NK cells were identified by the monoclonal an- at 0.50 Mg/ml of PHA, 6.10 at 2.5 Mg/ml, 6.10 at 5.0

tibodies CD56 and CD16, in the absence of CD3. Mg/ml, 5.93 at 10.0 Mg/ml, and 5.52 at 20.0 /ig/ml.

Psychosomatic Medicine 54:673-679 (1992) 675

E. A. BACHEN et al.

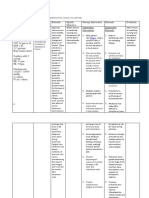

TABLE 1. Mean Lymphocyte Counts and PHA-Stimulated T-Lymphocyte Mitogenesis at Baseline and

Following the Experimental Period among Stressed Subjects and Unstressed Controls (Standard

Deviations in Parentheses)

Lymphocytes (cells/<mm3) T-Lymphocyte Proliferation (Acpm)'

0.5

CD4/CD8 CD4 CD8 CD3 CD19 NK 2.5 5.0 10.0 20.0

(Mg/ml)

Stress group

Baseline 1.5 718 522 1209 222 215 5.84 6.12 6.11 5.94 5.54

(0.5) (293) (262) (512) (92) (99) (0.25) (0.12) (0.13) (0.15) (0.20)

Experimental period 1.2 648 558 1154 204 290 5.83 6.09 6.09 5.92 5.51

(0.4) (245) (247) (479) (80) (124) (0.24) (0 13) (0.14) (0.18) (0.21)

Control subjects

Baseline 1.3 637 532 1100 203 209 5.84 6.06 6.07 5.90 5.50

(0.4) (154) (147) (183) (50) (94) (0.22) (0.08) (0.09) (0.09) (0 18)

Experimental period 1.2 616 523 1071 200 232 5.90 6.10 6.12 5.95 5 54

(0.4) (155) (145) (229) (46) (84) (0.22) (0.11) (0.10) (0.10) (0.18)

•' Values are the differences in counts per minute (logio) between stimulated and unstimulated samples, at each

concentration of PHA.

ments among stressed subjects, but no rose significantly between baseline and

change in controls (see Table 1). post-task measurements in stressed sub-

The ANOVAs for CD4 and CD8 popu- jects, but not among controls.

lations alone revealed a significant Period

main effect for CD4 lymphocytes (F(l,42)

= 9.49, p < 0.005), but not for CD8 cells;

in neither case was the Group X Period DISCUSSION

interaction reliable. Nonetheless, inspec-

tion of Table 1 reveals substantial base- In this study, subjects exposed to a brief

line-to-task changes in CD4 and CD8 lym- experimental stressor showed suppres-

phocytes among the experimental group. sion of PHA-stimulated T-cell prolifera-

Therefore, paired t tests were performed tion, as well as alterations in various cir-

separately for each condition, comparing culating lymphocyte subpopulations; the

pretask and post-task measurements for latter included a decreased ratio of

both variables. These analyses revealed CD4:CD8 lymphocytes (associated with

that CD8 cells increased and CD4 cells expanded CD8 and reduced CD4 cell pop-

decreased significantly from baseline to ulations) and an increase in the number

post-task measurements in the stressed of circulating NK cells. In contrast, control

group (t(32) = -2.84, p < 0.05); t(32) = subjects showed an increase in prolifera-

4.82, p < 0.0001), but did not change tive response, with no significant changes

among controls. in lymphocyte populations. It is possible

Finally, while no significant effects that the enhanced mitogenesis among the

were observed for total T (CD3) and B controls was due to protracted relaxation,

(CD19) lymphocytes, the Group X Period as these subjects were instructed to con-

interaction did achieve significance on tinue to sit quietly during the 21-minute

analysis of NK cells (F(l,41) = 4.99, p < 'task' period. Relatedly, other studies

0.05). Here again, the number of NK cells have demonstrated augmented immune

676 Psychosomatic Medicine 54:673-679 (1992)

CELLULAR IMMUNE RESPONSE

function in response to longer-term relax- lular immune function is sympathetically

ation interventions (12). mediated (13-15).

In a previous investigation, we observed Other recent studies reveal that natu-

a similar decrease in lymphocyte prolif- ralistic stressors (e.g., stressful life events,

eration and a selective increase in CD8 marital distress, and caregiving for a ter-

lymphocytes among stressed subjects, but minally ill family member) are also asso-

only in those individuals who showed the ciated with diminished lymphocyte pro-

most pronounced sympathoadrenal acti- liferation and CD4.CD8 cell ratios (1-3).

vation on exposure to the laboratory stres- However, while NK cell numbers consist-

sor (i.e., "high" sympathetic reactors, as ently rise following brief laboratory chal-

evidenced by marked rises in HR, BP, and lenges (8-10), naturalistic stressors have

venous plasma catecholamine concentra- generally been associated with a smaller

tions). Interestingly, the average HR and NK cell population (4). Differences in the

BP response elicited by the Stroop task in chronicity of stress may partially account

the present experiment approximated for the varying effects of naturalistic and

that of the "high" sympathetic reactors in laboratory stressors (8). It is interesting to

our earlier study. The relatively small HR note that the effect of restraint stress on

and BP responses of subjects identified in NK activity in rats depends on the dura-

the previous study as "low" sympathetic tion of the stressor, with NK activity fall-

reactors, in turn, were matched here by ing after repeated, but not acute, exposure

only six of 33 experimental subjects; to immobilization (16). The mechanisms

moreover, as in our earlier investigation, underlying differential immune changes

these few, less responsive individuals under acute and chronic stressor condi-

showed no changes between baseline and tions are not well understood. It is possible

task periods in comparable measures of that the distinct immunologic responses

immune response.4 Overall, then, we be- during chronic stress reflect the influence

of a more complex neuroendocrine mi-

lieve that the cellular-immune effects of lieu.

acute mental stress presented here are

consistent with findings reported previ- Antigen-induced lymphocyte prolifer-

ously by ourselves (7) and others (8-10). ation is one of the most basic immune

That our results are also similar to those system functions. Consequently, there is

obtained following epinephrine and iso- considerable interest in the mechanisms

proterenol infusions in humans (i.e., re- underlying altered proliferative responses

duced lymphocyte proliferation and associated with stress. It has been sug-

CD4:CD8 ratios, and increased NK cell gested that decreases in peripheral T-cell

populations) further suggests that the ef- mitogenesis may be due, in part, to con-

fects of acute psychological stress on cel- comitant shifts in lymphocyte popula-

tions, specifically, an increase in CD8 cells

and/or a diminished CD4:CD8 ratio. In

this regard, experimental subjects here

4

For these six individuals, mean baseline and

showed a relatively large reduction in the

post-task values of PHA-stimulated mitogenic re- CD4:CD8 ratio, accompanied by a signifi-

sponse [log,o (across five concentrations of PHA)], cant, albeit minimal, decline in mitogen-

were 5.91 and 5.90 cpm, respectively; corresponding esis following the task. Responses of con-

mean CD8 counts were 514 and 527 cells/mm3. trol subjects, on the other hand, were

Psychosomatic Medicine 54:673-679 (1992) 677

E. A. BACHEN et al.

characterized by a relatively large in- been shown to reduce IL-2 receptor

crease in T-lymphocyte proliferation expression on peripheral blood leuko-

without corresponding changes in cell cytes (5, 6), and both IL-2 production and

numbers. Hence, the relationship be- the expression of IL-2 receptors by acti-

tween mitogenesis and acute alterations vated T lymphocytes (neither of which

in lymphocyte populations remains un- were evaluated here) are necessary

clear. It is possible, too, that true associa- for antigen-stimulated proliferative re-

tions between these quantitative and sponses.

functional measures are partly obscured

by the fact that CD8 lymphocytes them-

selves subsume two distinct cell popula- This research was supported, in part, by

tions (true-suppressor and cytotoxic National Heart, Lung and BJood Institute

cells), and that only the former is im- Grant HL 40962 (SBMJ, NationaJ Institute

mune-suppressive. Future assessments of of AJJergies and Infectious Disease Grant

true-suppressor cell populations would Al 23072, National Institute of Mental

perhaps yield more consistent associa- Health Grant RSDA MH 00721 fSCj, and

tions with proliferative changes. Finally, Pathology, Education, and Research Foun-

alterations in T-cell mitogenesis may be dation (BSRJ.

influenced by numerous other factors as We thank E. HammiJJ /or performing

well. For instance, examination stress has lymphocyte assays.

REFERENCES

1. Kiecoll-Glaser JK, Kennedy S, Malkoff S, el al: Marital discord and immunity in males. Psychosom Med

50:213-229, 1988

2. Kiecolt-Glaser ]K. Glaser R, Shuttleworth EC, et al: Chronic stress and immunity in family caregivers

of Alzheimer's disease victims. Psychosom Med 49:523-535, 1987

3. McNaughton ME, Smith LW, Patterson TL, Grant I: Stress, social support, coping resources, and immune

status in elderly women. J Nerv Ment Dis 178460-461. 1990

4. Glaser R, Rice J, Speicher CE, et al: Stress depresses interferon production by leukocytes concomitant

with a decrease in natural killer cell activity. Behav Neurosci 100:675-678, 1986

5. Halvorscn R. Vassend O: Effects of examination stress on some cellular immunity functions. ] Psychosom

Res 31:693-701, 1987

6. Glaser R, Kennedy S, Lafuse WP. et al: Psychological stress-induced modulation of interleukin 2 receptor

gene expression and interleukin 2 production in peripheral blood leukocytes. Arch Gen Psychiatry

47:707-712, 1990

7. Manuck SB, Cohen S, Rabin BS, et al: Individual differences in cellular immune response to stress.

PsycholSci 2:111-115, 1991

8. Naliboff BD, Benton D, Solomon GF, et al: Immunological changes in young and old adults during brief

laboratory stress. Psychosom Med 53:121-132, 1991

9 Landmann RMA, Muller FB, Perini CH, et al: Changes in immunoregulatory cells induced by psycho-

logical and physical stress: Relationship to plasma catecholamines. Clin Exp Immunol 58:127-135, 1984

10. Landmann RMA. Perini C, Muller FB, Buhler FR: Catecholamine and leukocyte phenotype responses

to mental stress in subjects with anxiety or suppressed aggression. In Plotnikoff N. Murgo A, Faith R,

Wybran J (eds), Stress and Immunity. Boca Raton, Ann Arbor, London, CRC Press, 1991

11. Frankenhauser M, Mellis ), Rissler A. et al: Catecholamine excretion as related to cognitive and

emotional reaction patterns. Psychosom Med 30:109-120, 1968

678 Psychosomatic Medicine 54:673-679 (1992)

CELLULAR IMMUNE RESPONSE

12. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Williger D, et al: Psychosocial enhancement of immunocompetence in a

geriatric population. Health Psychol 4:25-41.1985

13. Crary B, Borysenko M, Sutherland DC, et al: Decrease in mitogen responsiveness of mononuclear cells

from peripheral blood after epinephrine administration in humans. J Immunol 130:694-697, 1983

14. Crary B, Hauser SL, Borysenko M, et al: Epinephrine-induced changes in the distribution of lymphocyte

subsets in peripheral blood of humans. J Immunol 131:1178-1181,1983

15. Van Tits LJH, Michel MC, Grosse-Wilde H, et al: Catecholamines increase lymphocyte B2-adrenergic

receptors via a B2-adrenergic, spleen-dependent process. Am J Physiol 258:E191-2O2. 1990

16. lrwin MR, Hauger RL: Adaptation to chronic stress. Temporal pattern of immune and neuroendocrins

correlates. Neuropsychopharmacology 1:239-242, 1988

Psychosomatic Medicine 54:673-679 (1992) 679

You might also like

- Why Nature & Nurture Won't Go AwayDocument13 pagesWhy Nature & Nurture Won't Go AwaySoulyogaNo ratings yet

- Brief Meditation BenefitsDocument5 pagesBrief Meditation BenefitschandusgNo ratings yet

- Zazen and Cardiac VariabilityDocument10 pagesZazen and Cardiac VariabilitySoulyogaNo ratings yet

- Yoga As A Complementary Treatment of DepressionDocument10 pagesYoga As A Complementary Treatment of DepressionSoulyogaNo ratings yet

- 1472 6882 7 43Document8 pages1472 6882 7 43Byaruhanga EmmanuelNo ratings yet

- A Theoretical AppraisalDocument9 pagesA Theoretical AppraisalSoulyogaNo ratings yet

- Yoga MeditationDocument4 pagesYoga MeditationSoulyogaNo ratings yet

- Yoga As A Complementary Treatment of DepressionDocument10 pagesYoga As A Complementary Treatment of DepressionSoulyogaNo ratings yet

- Yoga InterventionDocument5 pagesYoga InterventionSoulyogaNo ratings yet

- Yoga For DepressionDocument12 pagesYoga For DepressionSoulyogaNo ratings yet

- Yoga For Cancer Patients and SurvivorsDocument7 pagesYoga For Cancer Patients and SurvivorsSoulyogaNo ratings yet

- Yoga As A Complementary Treatment of DepressionDocument10 pagesYoga As A Complementary Treatment of DepressionSoulyogaNo ratings yet

- Tt10 Kelly AeDocument8 pagesTt10 Kelly AeSoulyogaNo ratings yet

- Using Self-Report Assessment MethodsDocument19 pagesUsing Self-Report Assessment MethodsSoulyogaNo ratings yet

- Pic Render 6Document3 pagesPic Render 6SoulyogaNo ratings yet

- Systemic DiseaseDocument5 pagesSystemic DiseaseSoulyogaNo ratings yet

- LazarVO2 NO Med Sci Monitor 06Document10 pagesLazarVO2 NO Med Sci Monitor 06SoulyogaNo ratings yet

- Using Self-Report Assessment MethodsDocument19 pagesUsing Self-Report Assessment MethodsSoulyogaNo ratings yet

- Teaching Self CareDocument11 pagesTeaching Self CareSoulyogaNo ratings yet

- TT11 Blankfield RPDocument8 pagesTT11 Blankfield RPSoulyogaNo ratings yet

- The DevelopmentDocument28 pagesThe DevelopmentSoulyogaNo ratings yet

- TT9 Larden CNDocument13 pagesTT9 Larden CNSoulyogaNo ratings yet

- The Role of AutonomicDocument4 pagesThe Role of AutonomicSoulyogaNo ratings yet

- Teaching Self CareDocument11 pagesTeaching Self CareSoulyogaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Long Term Combined Yoga Practice On The Basal Metabolic RateDocument6 pagesThe Effect of Long Term Combined Yoga Practice On The Basal Metabolic Rateapi-3750171No ratings yet

- Stress and Immunity in Humans XXDocument16 pagesStress and Immunity in Humans XXSoulyogaNo ratings yet

- Teaching Self CareDocument11 pagesTeaching Self CareSoulyogaNo ratings yet

- Stress and Immunity in Humans XXDocument16 pagesStress and Immunity in Humans XXSoulyogaNo ratings yet

- Stress and Immunity in Humans XXDocument16 pagesStress and Immunity in Humans XXSoulyogaNo ratings yet

- Psychological Stress and AntibodyDocument9 pagesPsychological Stress and AntibodySoulyogaNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- HCC Surveillance in An Era of BiomarkersDocument48 pagesHCC Surveillance in An Era of BiomarkersRobert G. Gish, MDNo ratings yet

- The Dark Side of WheatDocument77 pagesThe Dark Side of WheatSayer JiNo ratings yet

- Management of Recurrent MiscarriagesDocument11 pagesManagement of Recurrent MiscarriagesmarinaNo ratings yet

- Plant Pathogens Principles of Plant PathologyDocument376 pagesPlant Pathogens Principles of Plant PathologyChirag GuptaNo ratings yet

- Toxicological Evaluation PDFDocument291 pagesToxicological Evaluation PDFMaría SolórzanoNo ratings yet

- CH 11 - Study GuideDocument4 pagesCH 11 - Study Guideapi-342334216No ratings yet

- Evolution - A Golden GuideDocument164 pagesEvolution - A Golden GuideKenneth83% (12)

- Mechanisms of Bacterial PathogenesisDocument34 pagesMechanisms of Bacterial PathogenesisMamta ShindeNo ratings yet

- An Updated Review On Bluetongue Virus Epidemiology Pathobiology and Advances in Diagnosis and Control With Special Reference To India PDFDocument65 pagesAn Updated Review On Bluetongue Virus Epidemiology Pathobiology and Advances in Diagnosis and Control With Special Reference To India PDFamena wajeehNo ratings yet

- Baby BluesDocument25 pagesBaby BluesMichael AlexanderNo ratings yet

- Ted Talk Reflection 1Document3 pagesTed Talk Reflection 1api-242138662No ratings yet

- Qubit 4 Fluorometer-Fast Answers For Precious Samples: Find Out If You Have Enough DNA or RNA For Your ExperimentDocument2 pagesQubit 4 Fluorometer-Fast Answers For Precious Samples: Find Out If You Have Enough DNA or RNA For Your ExperimentmisuakechiNo ratings yet

- Triple Negative Breast Cancer: Understanding The Molecular, Biologic, and Clinical CharacteristicsDocument24 pagesTriple Negative Breast Cancer: Understanding The Molecular, Biologic, and Clinical Characteristicsleeann_swenson100% (1)

- NCP - FatigueDocument3 pagesNCP - Fatigueitsmeaya100% (1)

- Radiobiology DilshadDocument78 pagesRadiobiology DilshadAJAY K VNo ratings yet

- Primary Glomerulonephritis UG LectureDocument50 pagesPrimary Glomerulonephritis UG LectureMalik Mohammad AzharuddinNo ratings yet

- Plasmapheresis Treats Antiphospholipid SyndromeDocument17 pagesPlasmapheresis Treats Antiphospholipid SyndromeEliDavidNo ratings yet

- Molecular Basis of Inheritance TheoryDocument40 pagesMolecular Basis of Inheritance TheoryRohit SahuNo ratings yet

- Unit 4-Lecture 1-Hemorrhagic Disorders and Laboratory AssessmentDocument89 pagesUnit 4-Lecture 1-Hemorrhagic Disorders and Laboratory AssessmentBecky GoodwinNo ratings yet

- Chi Square TestDocument75 pagesChi Square Testdrmsupriya091159100% (1)

- Building On Success: A Bright Future For Peptide TherapeuticsDocument7 pagesBuilding On Success: A Bright Future For Peptide TherapeuticsDiana PachónNo ratings yet

- Cytokines - IntroductionDocument2 pagesCytokines - IntroductionTra gicNo ratings yet

- Bacteria-Genetic TransferDocument57 pagesBacteria-Genetic TransferKA AngappanNo ratings yet

- Introducing The Sorush Cancer Treatment Protocol (SCTP)Document18 pagesIntroducing The Sorush Cancer Treatment Protocol (SCTP)SorushNo ratings yet

- NSG 126 Serologic Studies (Part 5-8)Document11 pagesNSG 126 Serologic Studies (Part 5-8)Angelica Charisse BuliganNo ratings yet

- PredicineATLAS WhitepaperDocument8 pagesPredicineATLAS WhitepapersagarkarvandeNo ratings yet

- IAL Biol WBI05 Jan18 Scientific ArticleDocument8 pagesIAL Biol WBI05 Jan18 Scientific ArticleMoeez AkramNo ratings yet

- AutoGenomics Intl-AACC, LADocument63 pagesAutoGenomics Intl-AACC, LAmohdkhairNo ratings yet

- Root Resorption What We Know and How It Affects Our Clinical PracticeDocument15 pagesRoot Resorption What We Know and How It Affects Our Clinical Practicedrgeorgejose7818No ratings yet

- Genomics of Plants and Fungi - Prade and BohnertDocument395 pagesGenomics of Plants and Fungi - Prade and BohnertFernanda CastroNo ratings yet