Professional Documents

Culture Documents

MH0050 - Quality Management in Healthcare Services

Uploaded by

Rahul GuptaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

MH0050 - Quality Management in Healthcare Services

Uploaded by

Rahul GuptaCopyright:

Available Formats

MH0050 – Quality Management in Healthcare Services

Q.1. Explain the PDCA Cycle in detail?

Sol-

Description

The PDCA (or PDSA) Cycle was originally conceived by Walter Shewhart in 1930's, and

later adopted by W. Edwards Deming. The model provides a framework for the improvement

of a process or system. It can be used to guide the entire improvement project, or to develop

specific projects once target improvement areas have been identified.

Use

The PDCA cycle is designed to be used as a dynamic model. The completion of one turn of

the cycle flows into the beginning of the next. Following in the spirit of continuous quality

improvement, the process can always be reanalyzed and a new test of change can begin. This

continual cycle of change is represented in the ramp of improvement. Using what we learn in

one PDCA trial, we can begin another, more complex trial.

Plan - a change or a test, aimed at improvement.

In this phase, analyze what you intend to improve, looking for areas that hold opportunities

for change. The first step is to choose areas that offer the most return for the effort you put in-

the biggest bang for your buck.

Do - Carry out the change or test (preferably on a small scale).

Implement the change you decided on in the plan phase.

RAHUL GUPTA, MBAHCS (4th SEM), SUBJECT CODE-MH0050, SET-1 Page 1

MH0050 – Quality Management in Healthcare Services

Check or Study – What was learned? What went wrong?

This is a crucial step in the PDCA cycle. After you have implemented the change for a short

time, you must determine how well it is working. Is it really leading to improvement in the

way you had hoped? You must decide on several measures with which you can monitor the

level of improvement. Run Charts can be helpful with this measurement.

Act - Adopt the change, abandon it, or run through the cycle again.

After planning a change, implementing and then monitoring it, you must decide whether it is

worth continuing that particular change. If it consumed too much of your time, was difficult

to adhere to, or even led to no improvement, you may consider aborting the change and

planning a new one. However, if the change led to a desirable improvement or outcome, you

may consider expanding the trial to a different area, or slightly increasing your complexity.

This sends you back into the Plan phase and can be the beginning of the ramp of

improvement.

Student Section: Improving Your History-Taking Skills

In the first year of medical school, many students are taught to take histories from patients.

Some students are comfortable with this process, but others feel like they're barely keeping

their heads above water. Whether you are the former or the latter, it would be beneficial to get

feedback on your strengths and weaknesses so that you can become a better history taker. The

PDCA cycle does just that. It allows medical students to gather knowledge about their

interviewing skills and then walks them through different tests of change to see whether the

desired improvement really works.

Example 3: Feedback for the Medical Student

Jake is a first-year medical student at Dartmouth Medical School (DMS). He visits a local

primary care provider's office twice a month, where he works on interviewing different

patients. Although he is comfortable talking to patients, he is unsure whether he's asking them

the right questions. Sometimes he is at a loss for things to ask, and there are moments of

awkward silence. The provider that Jake works with, Dr. Eastman is a kind man who teaches

Jake a lot about medicine but never gives Jake feedback on how he is doing.

• What is he trying to accomplish? Jake would like to improve his history-taking skills.

• How will he know that a change is an improvement? Jake knows that he needs more

information concerning his history-taking skills. The only way he can get that

information is through feedback from others in the medical field. He decides that the

most important measure of his performance should come from Dr. Eastman.

• What changes can he make that will result in improvement? Jake is unsure how to

answer this question. He feels confident in his ability to take a patient history. The

only weakness he feels is a lack of questions to ask.

Cycle 1

Plan: Jake asks Dr. Eastman to sit in on at least two interviews so that he can receive

immediate feedback. On any interview that Dr. Eastman doesn't sit in on, Jake will see the

patient first and report all his findings.

RAHUL GUPTA, MBAHCS (4th SEM), SUBJECT CODE-MH0050, SET-1 Page 2

MH0050 – Quality Management in Healthcare Services

Do: Dr. Eastman is very busy the next time Jake visits him, and he sits in on only one

interview. However, he has his nurse practitioner, Ms. Irvine, observe Jake for two additional

interviews. Because Dr. Eastman is so busy, Jake doesn't have time to report his findings to

him.

Check: The feedback that Dr. Eastman and Ms. Irvine gave Jake was very different. Dr.

Eastman told Jake that he was doing a good job but that he forgot to ask a couple of questions

in the HPI. Ms. Irvine said that Jake needed to work on asking open-ended questions and

pausing to let the patient think. In addition, she mentioned that he completely left out the

social history.

Act: Jake decides to make some changes that will affect both his history taking and the

feedback he is receiving. He needs more feedback from both Dr. Eastman and Ms. Irvine, in

addition to other sources such as his classmates and the doctors he works with at school.

Cycle 2

Plan: Jake decides to continue receiving regular feedback from both Dr. Eastman and Ms.

Irvine. He specifically asks Dr. Eastman what questions he may have missed while

interviewing and what the doctor thinks of his interviewing style. Jake also works with other

medical students at mock interviewing. He tries to find a group of four so that two can watch

and critique while Jake interviews the fourth student. Finally, DMS tests its students'

interviewing skills twice a year during observed structural clinical encounters (OSCEs). In

this process, medical students are videotaped while they interview patients (paid actors). Jake

just went through his first OSCE a month ago. He received feedback from the mock patient

he interviewed, but he also wants feedback from some of the physicians who run the OSCE

program. He sets up a time to meet with them to watch his video.

Do: It takes only two weeks for Jake to receive more feedback. Dr. Eastman seems more

comfortable criticizing Jake now that he knows what he wants. Also, Jake and his fellow

classmates have a lot of fun doing the mock interviews.

Check: Jake receives a lot more feedback from Dr. Eastman, who notes that Jake tends to

rush patients and ask closed-ended (yes or no) questions. "Take the time to let them tell their

story," Ms. Irvine tells him. In the OSCE videotape, Jake and the physician who watched it

with him notice that he needs to work on his skills taking blood pressures, that he missed the

social history, and that he didn’t ask any questions regarding the patient's habits. In addition,

the videotape reveals Jake's poor habit of rushing the patient and asking closed-ended

questions. In the mock interviews with his peers, Jake notices that he is slowing down and

does a better job covering the social history aspect of the interview.

RAHUL GUPTA, MBAHCS (4th SEM), SUBJECT CODE-MH0050, SET-1 Page 3

MH0050 – Quality Management in Healthcare Services

Act: Jake decides to continue receiving regular feedback from Dr. Eastman and Ms. Irvine.

He also continues to meet with his peers to work on his interviewing skills and receive

criticism from them. Jake works on all the weaknesses he discovers in these learning sessions

when he sees real patients in Dr. Eastman's office.

Jake's major improvements came from his ability to study his changes in the check phase of

the PDCA cycle. In this phase, Jake was able to recognize that Dr. Eastman and Ms. Irvine

provided different kinds of feedback. This knowledge led him to a second PDCA cycle in

which he experimented with using more and different health care professionals to test his

history-taking performance. As Jake proceeds with each cycle, he will gain more knowledge

and continue to improve his history-taking skills.

Clinician Section: Improving Your Office

As a first-year medical student, your role can extend far beyond just practicing your history-

taking skills. You have an untainted perspective that attacks problems with a freshness that

your office is probably unaccustomed to and will probably treasure. But simply throwing out

ideas for change every time one pops into your head is not the way to effect change; instead,

use the PDCA cycle. Let’s see how it works in an office setting like yours.

Example- The Medical Student Who Made a Difference

Tucker is a first-year medical student who follows a preceptor in a small family practice

office. At a recent lunch break at this office, Tucker listened in as the four physicians

complained about the high volume of patients they were referring to specialists.

What are they trying to accomplish? Improvement is certainly needed in this referral process.

How will they know that a change is an improvement? The major measure that this practice is

interested in is the number and type of referrals. Another metric the practice is concerned

about is financial productivity.

What changes can they make that will result in improvement? Tucker knew that there were

opportunities for improvement here, so he decided to apply the PDCA cycle.

Cycle 1

Plan: Tucker asked his preceptor for all her referrals in the past six months. After stratifying

the referrals by specialty, Tucker realized that 70 percent of the patients went to the

orthopaedics department at the local tertiary care centre, mostly for sprained ankles and knee

trauma. He also noted that a number of the initial calls to the family practice came when the

office was closed, on weekends and after 5 p.m. Tucker presented this information to his

preceptor, and together they realized that the practice might benefit from a change in its

delivery of orthopaedic care. Their plan was simple: have the orthopaedics department at the

local hospital train the four physicians in the practice how to treat sprained ankles and some

knee trauma. Since the local hospital physicians are on a salaried status, not fee-for-service,

there is no disincentive for this training.

RAHUL GUPTA, MBAHCS (4th SEM), SUBJECT CODE-MH0050, SET-1 Page 4

MH0050 – Quality Management in Healthcare Services

Do: The family practitioners arranged for a one-week, after-hours training session in these

two areas of high-volume injuries. They decided that they would test this change for two

months to determine whether they would be able to reduce the number of referrals and

maintain their patients' continuum of care at the practice. They also decided to stay open until

9 p.m. every Wednesday and from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. every Sunday as an open clinic. One

physician, one nurse, and one administrator would staff each open clinic.

Check: The practice is interested in the number and type of referrals, as well as financial

productivity. After two months of implementing this change, the number of orthopaedic

referrals fell by 30 percent compared with the same period in previous years. By staying open

longer, treating more patients, and referring less, the profits at the practice were 18 percent

higher than they were during those two months in any previous year. Further, although they

had no formal metric for patient satisfaction, all four physicians received positive feedback

for the orthopaedic care they were delivering and for their new convenient open clinic.

Act: Clearly, this change resulted in major improvement. The physicians decided to institute

this change permanently. Because of its success, the physicians are considering applying this

technique to other specialties to which they refer patients.

As demonstrated by this case study, the PDCA cycle can be applied to any situation. By

employing the PDCA cycle, the family practice first carefully assessed what needed to be

changed and then implemented an effective improvement plan. Implementing an

improvement plan that is hastily selected rarely leads to effective change. This family practice

did not fall into the trap of shooting without properly aiming.

The Ramp of Improvement

This is a schematic representation of the use of the PDCA cycle in the improvement process.

As each full PDCA cycle comes to completion, a new and slightly more complex project can

be undertaken. This rolling over feature is integral to the continual improvement process.

RAHUL GUPTA, MBAHCS (4th SEM), SUBJECT CODE-MH0050, SET-1 Page 5

MH0050 – Quality Management in Healthcare Services

Q.2. Explain in detail the dimensions of quality in healthcare?

Sol –

Quality of care should be defined in light of both technical standards and patients'

expectations. While no single definition of health service quality applies in all situations, the

following common definitions are helpful guides:

Quality Assurance is that set of activities that are carried out to monitor and improve

performance so that the care provided is as effective and as safe as possible (Quality

Assurance Project, 1993).

The application of medical science and technology in a way that maximizes its benefits to

health without correspondingly increasing its risks. The degree of quality is, therefore, the

extent to which the care provided is expected to achieve the most favourable balance of risks

and benefits.

Proper performance (according to standards) of interventions that are known to be safe, that

are affordable to the society in question, and that have the ability to produce an impact on

mortality, morbidity, disability, and malnutrition (M.I. Roemer and C. Montoya Aguilar,

WHO, 1983).

The most comprehensive and perhaps the simplest definition of quality is that used by

advocates of total quality management (W. Edwards Deming, 1982): "Doing the right thing

right, right away." Experts generally recognize several distinct dimensions of quality that vary

in importance depending on the context in which a QA effort takes place. The following nine

dimensions of quality have been developed from the technical literature on quality and

synthesize ideas from various QA experts. Together, they provide a useful framework that

helps health teams to define, analyze, and measure the extent to which they are meeting

program standards for clinical care and for management services that support service

delivery. While all of these dimensions are relevant to developing country settings, not all

nine deserve equal weight in every program. Each should be defined according to the local

context and specific programs.

Technical performance: The degree to which the tasks carried out by health workers and

facilities meet expectations of technical quality (i.e., adhere to standards)

Access to services: The degree to which healthcare services are unrestricted by geographic,

economic, social, organizational, or linguistic barriers

Effectiveness of care: The degree to which desired results (outcomes) of care are achieved

Efficiency of service delivery: The ratio of the outputs of services to the associated costs of

producing those services

Interpersonal relations: Trust, respect, confidentiality, courtesy, responsiveness, empathy,

effective listening, and communication between providers and clients

Continuity of services: Delivery of care by the same healthcare provider throughout the

course of care (when appropriate) and appropriate and timely referral and communication

between providers

Safety: The degree to which the risks of injury, infection, or other harmful side effect are

minimized

Physical infrastructure and comfort: The physical appearance of the facility, cleanliness,

RAHUL GUPTA, MBAHCS (4th SEM), SUBJECT CODE-MH0050, SET-1 Page 6

MH0050 – Quality Management in Healthcare Services

comfort, privacy, and other aspects that are important to clients

Choice: As appropriate and feasible, client choice of provider, insurance plan, or treatment.

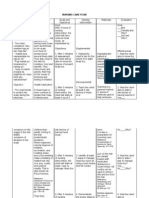

Q.3. Explain the 7 quality control tools?

Sol –

The Seven Basic Tools of Quality is a designation given to a fixed set of graphical

techniques identified as being most helpful in troubleshooting issues related to quality. They

are called basic because they are suitable for people with little formal training in statistics and

because they can be used to solve the vast majority of quality-related issues.

The tools are:

The cause-and-effect or Ishikawa diagram

The check sheet

The control chart

The histogram

The Pareto chart

The scatter diagram

Stratification (alternately flow chart or run chart)

The first is the check sheet, which shows the history and pattern of variations. This

tool is used at the beginning of the change process to identify the problems and collect

data easily.

The team using it can study observed data (a performance measure of a process) for

patterns over a specified period of time. It is also used at the end of the change process

to see whether the change has resulted in permanent improvement.

The Pareto chart is named after Wilfred Pareto, the Italian economist who

determined that wealth is not evenly distributed. The chart shows the distribution of

items and arranges them from the most frequent to the least frequent, with the final

bar being miscellaneous.

The Pareto chart is used to define problems, to set their priority, to illustrate the

problems detected and determine their frequency in the process. It is a graphic picture

of the most frequent causes of a particular problem. Most people use it to determine

where to put their initial efforts to get maximum gain.

The cause and effect diagram is also called the "fishbone chart" because of its

appearance and the Ishikawa chart after the man who popularised its use in Japan. It is

RAHUL GUPTA, MBAHCS (4th SEM), SUBJECT CODE-MH0050, SET-1 Page 7

MH0050 – Quality Management in Healthcare Services

used to list the cause of particular problems. Lines come off the core horizontal line to

display the main causes; the lines coming off the main causes are the sub causes.

This tool is used to figure out any possible causes of a problem. It allows a team to

identify, explore, and graphically display, in increasing detail, all of the possible

causes related to a problem or condition to discover its root cause(s).

The histogram is a bar chart showing a distribution of variables. This tool helps

identify the cause of problems in a process by the shape as well as the width of the

distribution. It shows a bar chart of accumulated data and provides the easiest way to

evaluate the distribution of data.

Then there's the scatter diagram, which shows the pattern of relationship between

two variables that are thought to be related.

The closer the points are to the diagonal line, the more closely there is a one-to-one

relationship. The scatter diagram is a graphical tool that plots many data points and

shows a pattern of correlation between two variables.

Graphs are among the simplest and best techniques to analyse and display data for

easy communication in a visual format. Data can be depicted graphically using bar

graphs, line charts, pie charts and control charts. While the first three are commonly

used, the last is a line chart with control limits.

By mathematically constructing control limits at three standard deviations above and

below the average, one can determine what variation is due to normal ongoing causes

(common causes) and what variation is produced by unique events (special causes).

By eliminating the special causes first and then reducing common causes, quality can

be improved. Control chart provides control limits that are three standard deviations

above and below average, whether or not our process is in control.

This tool enables the user to monitor, control and improve process performance over

time by studying variation and its source.

The designation arose in post-war Japan, inspired by the seven famous weapons of Benkei At

that time, companies that had set about training their workforces in statistical quality

control found that the complexity of the subject intimidated the vast majority of their workers

and scaled back training to focus primarily on simpler methods which suffice for most

quality-related issues anyway.[5]

The Seven Basic Tools stand in contrast with more advanced statistical methods such

as survey sampling, acceptance sampling, statistical hypothesis testing, experiments,

multivariate, and various methods developed in the field of operations research.

RAHUL GUPTA, MBAHCS (4th SEM), SUBJECT CODE-MH0050, SET-1 Page 8

You might also like

- Health Care ProjectDocument84 pagesHealth Care ProjectRahul Gupta80% (10)

- MH0049 - Legal Aspects in Healthcare AdministrationDocument12 pagesMH0049 - Legal Aspects in Healthcare AdministrationRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Consumer Behavior Towards Health Care ProductsDocument36 pagesAnalysis of Consumer Behavior Towards Health Care ProductsRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- MB0036-Strategic Management & Business PolicyDocument14 pagesMB0036-Strategic Management & Business PolicyRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- MB0037-International Business ManagementDocument20 pagesMB0037-International Business ManagementRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- MH0048 - Management of Healthcare Human ResourcesDocument12 pagesMH0048 - Management of Healthcare Human ResourcesRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- MH0047 - Public Relations and Marketing of Healthcare OrganizationDocument13 pagesMH0047 - Public Relations and Marketing of Healthcare OrganizationRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- MH0043 - Finance, Economics and Materials Management in Healthcare ServicesDocument10 pagesMH0043 - Finance, Economics and Materials Management in Healthcare ServicesRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- MH0038 Research MethodologyDocument15 pagesMH0038 Research MethodologyRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- MH0041 - Hospital Organization, Operations and PlanningDocument7 pagesMH0041 - Hospital Organization, Operations and PlanningRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- MB0036-Strategic Management & Business PolicyDocument14 pagesMB0036-Strategic Management & Business PolicyRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Final Assignment On PMDocument11 pagesFinal Assignment On PMRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- MH0040 - Health AdministrationDocument12 pagesMH0040 - Health AdministrationRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- MH0042 - Hospital and Healthcare Information ManagementDocument10 pagesMH0042 - Hospital and Healthcare Information ManagementRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- MH0039-Legal Aspect of BusinessDocument12 pagesMH0039-Legal Aspect of BusinessRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Final Assignment On POMDocument13 pagesFinal Assignment On POMRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Final Assignment On orDocument23 pagesFinal Assignment On orRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Final Assignment On MISDocument17 pagesFinal Assignment On MISRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Final Assignment On StatsDocument36 pagesFinal Assignment On StatsRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Final Assignment On MarketingDocument29 pagesFinal Assignment On MarketingRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Final Assignment On FMDocument13 pagesFinal Assignment On FMRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Final Assignment of MPOBDocument47 pagesFinal Assignment of MPOBRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Final Assignment On AccountsDocument14 pagesFinal Assignment On AccountsRahul Gupta100% (1)

- Final Assignment of HRMDocument28 pagesFinal Assignment of HRMRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Final Assignment of MEDocument24 pagesFinal Assignment of MERahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Artificial Intelligence - Imaging's Next FrontierDocument8 pagesArtificial Intelligence - Imaging's Next FrontierEdgar DauzonNo ratings yet

- ENG - S.A.F.E.R.®/NeoGraft® Hair Transplant Technique & DeviceDocument3 pagesENG - S.A.F.E.R.®/NeoGraft® Hair Transplant Technique & DeviceMedicamatNo ratings yet

- The Role of Dispensers in The Rational Use of DrugsDocument19 pagesThe Role of Dispensers in The Rational Use of DrugsAci LusianaNo ratings yet

- Surgery CssDocument13 pagesSurgery CssNaren ShanNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of Arrhythmias: Causes and MechanismsDocument53 pagesPathophysiology of Arrhythmias: Causes and MechanismsAmanuel MaruNo ratings yet

- Andre Hannah NursingresumeDocument1 pageAndre Hannah Nursingresumeapi-450112281No ratings yet

- Dka CalculatorDocument1 pageDka CalculatordelfiaNo ratings yet

- Sample Case StudyDocument91 pagesSample Case StudyGeleine Curutan - Onia100% (4)

- PediculosisDocument3 pagesPediculosisDarkCeades50% (4)

- Guide to Chemotherapy Drugs and Side EffectsDocument38 pagesGuide to Chemotherapy Drugs and Side EffectsTrixia CamporedondoNo ratings yet

- UG Curriculum Vol II PDFDocument247 pagesUG Curriculum Vol II PDFRavi Meher67% (3)

- Ventilator Wave Form and InterpretationDocument59 pagesVentilator Wave Form and InterpretationArnab SitNo ratings yet

- Doh Requirements Level 1 HospitalDocument50 pagesDoh Requirements Level 1 HospitalFerdinand M. Turbanos100% (4)

- Dorothy M. Adcock, MDDocument4 pagesDorothy M. Adcock, MDพอ วิดNo ratings yet

- Communicating With Patients From Different Cultural BackgroundDocument24 pagesCommunicating With Patients From Different Cultural BackgroundRiska Aprilia100% (1)

- Gaumard Catálogo 2014Document232 pagesGaumard Catálogo 2014renucha2010No ratings yet

- Expanded and Extended Role of NurseDocument31 pagesExpanded and Extended Role of NurseMaria VarteNo ratings yet

- Arterial Line Waveform Interpretation UHL Childrens Intensive Care GuidelineDocument5 pagesArterial Line Waveform Interpretation UHL Childrens Intensive Care GuidelineDhony100% (1)

- Aims and ObjectivesDocument13 pagesAims and Objectivesmamun183No ratings yet

- Ambu BagDocument29 pagesAmbu BagJessa Borre100% (2)

- Ayurvedic Management of Multiple SclerosisDocument4 pagesAyurvedic Management of Multiple SclerosisLife LineNo ratings yet

- Fdar Psychiatric DutyDocument2 pagesFdar Psychiatric DutyErica Maceo MartinezNo ratings yet

- Terapi Cairan PD Syok KardiogenikDocument27 pagesTerapi Cairan PD Syok KardiogenikSri AsmawatiNo ratings yet

- SCHEDULE OPTIMIZEDDocument2 pagesSCHEDULE OPTIMIZEDAnonymous iScW9lNo ratings yet

- Rationale: Most Patients Prescribed To Receive Platelet Transfusions Exhibit Moderate ToDocument2 pagesRationale: Most Patients Prescribed To Receive Platelet Transfusions Exhibit Moderate TojoanneNo ratings yet

- Chap 05 Abdominal TraumaDocument24 pagesChap 05 Abdominal TraumaAndra SNo ratings yet

- Final Copy of Assessment One (Quality Improvement)Document11 pagesFinal Copy of Assessment One (Quality Improvement)MadsNo ratings yet

- HCW NigeriaDocument12 pagesHCW NigeriaFrancis Njihia KaburuNo ratings yet

- Scheduling Procedures Cath LabDocument3 pagesScheduling Procedures Cath Labrajneeshchd100% (1)

- CGHS Rates 2014 - AhmadabadDocument72 pagesCGHS Rates 2014 - AhmadabadJayakrishna ReddyNo ratings yet