Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jahn - Luxury Brands

Uploaded by

kash811Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jahn - Luxury Brands

Uploaded by

kash811Copyright:

Available Formats

1 THE ROLE OF SOCIAL MEDIA FOR

LUXURY-BRANDS – MOTIVES FOR

CONSUMER ENGAGEMENT AND

OPPORTUNITIES FOR BUSINESSES

Dipl.-Kfm. Benedikt Jahn (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München), Prof. Dr. Werner

Kunz (University of Massachusetts Boston), Univ.-Prof. Dr. Anton Meyer (Ludwig-

Maximilians-Universität München)

1.1 SOCIAL MEDIA IN A WORLD OF LUXURY

BRANDS

Social Media today is omnipresent and Brand pages on online channels like Facebook, Google+,

Twitter, or YouTube are getting more and more popular around the world. The customer engagement

on these platforms has changed the idea of relationship marketing. Traditionally, companies have tried

to reach out and build up relationships with customers through marketing activities like reward

programs and direct marketing. In this old world, customers were passive “receivers” of relationship

activities as well as brand messages and the company had control over the brand development

process. Today, customers engage and act as co-creators and multipliers of brand messages

[19,25,30].

Almost every successful brand-oriented company operates at least one brand page on Facebook,

Twitter, or YouTube. Luxury brands like Armani, Burberry or Dolce&Gabbana have increasingly

invested in social media [38]. Nevertheless many marketing managers are still skeptical and

questioning whether it is worthwhile putting so much effort into the social media phenomenon, and if it

pays off. Especially in the luxury product industry, marketers doubt the value of the mass medium

Internet for the unique relationship between exclusive luxury brands and their customers [34,16]. This

shows the need to understand the effects of social media on the customer-relationship in general and

particularly for luxury brands.

Therefore, this article discusses the relevance of social media for luxury brands and studies how

social media brand pages affect the customer-brand relationship. We begin with a brief overview of

the literature regarding luxury brands and social media. We then discuss the value of social media for

luxury brands. Subsequently we present a general framework that describes how brand pages can

contribute to brand loyalty of the customer and how brand page participation is influenced by various

consumer values. Further, we describe a study that has tested this general framework and discuss

managerial implications for the management of luxury brands.

As a central result of our study we show that social media can be seen as a business opportunity.

Brand pages are an excellent tool for brand management, because they have measurable effects on

the customer brand relationship. Brand managers should embrace this new channel and understand

how to work with it in a contemporary fashion. Our study contributes to the ongoing discussion about

the value of social media and shows motives and effects of social media customer engagement.

1.2 A RESEARCH REVIEW FOR LUXURY BRANDING

AND SOCIAL MEDIA

1.2.1 Luxury Brands

In the past luxury brands were a privilege for a wealthy minority. But recently luxury companies have

launched new product lines and extensions to target a wider range of consumers. As a result, luxury

brands became affordable to many average consumers and the luxury market has been growing over

the last 20 years [44,50,46]. This democratization of luxury [44,50] shows the relevance of the

24.04.12 – 08:42 Jahn_Kunz_Meyer_Luxusmarken_Burmann_König_Final.docx Seite 2 von 13

phenomenon for mass marketing.

Despite the omnipresence of luxury brands in our everyday life, it is not easy to define the term “luxury

brand”, because luxury is very subjective and relative [5,13,39,49]. For example, a millionaire flying on

business class will treat it as normality, but for a normal employee it would be luxurious. While in some

regions of the world taking a shower in the morning is quite normal, in others it would be perceived as

a luxury. While forty years ago, having a refrigerator was something special, today almost every

household has one [26]. Sekora [41] defines luxury as “anything unneeded”. Following the Oxford

Latin Dictionary [36], luxury stands for an extravagant lifestyle. What extravagant means, depends on

a common sense about what is normal at a specific date, in a specific region for an average person.

Marketers in general see the label “luxury” as chance to differentiate a brand in a category and make it

more appealing for customers [20,12]. This usually goes hand in hand with a price premium [50].

Accordingly Nueno and Quelch [33] they define luxury brands as “those whose ratio of functionality to

price is low, while the ratio of intangible and situational utility to price is high”. Traditionally luxury

goods are described as goods, which bring prestige apart from any functional utility [17]. They are

characterized by adjectives as exclusive, extremely expensive, luxurious, exquisite, elitist, high quality,

excellent, hedonistic, rare, precious, crafted, glamorous, powerful and magic [21,14,49-50]. Luxury

brands satisfy not only functional but also psychological needs, and the psychological benefits seem

to be the main distinguishing factor [50].

In general, the perception of luxury can be separated in non-personal and personal perceptions. The

non-personal perceptions can also be described as interpersonal or socially oriented [44,50,43].

Socially oriented consumers’ are buying luxury brands to display their status, success and distinction

in peer groups. The brand works as a symbol of prominence and tastefulness and signals membership

in a certain social group [44]. Personal perceptions are in contrast functioning to impress other people.

They stand for personally affective benefits as hedonic pleasure, personally symbolic benefits as the

expression of the consumer’s internal self, and personally utilitarian benefits, when the brand matches

with individual attitudes of the consumer and his tastes for quality [44]. Vigneron and Johnson [49-50]

are proposing five main factors of luxury that differentiate between non-personal and personal

perceptions of luxury (see figure 1.1).

Platzhalter Abbildung Start

Figure 1.1 Framework of luxury brands

Bildrechte: Vigneron & Johnson 2004

Datei: figure1_1.jpg

24.04.12 – 08:42 Jahn_Kunz_Meyer_Luxusmarken_Burmann_König_Final.docx Seite 3 von 13

Platzhalter Abbildung Stop

The conspicuousness dimension is based on the assumption that luxury brands are representing

prestige or social status, apart from any functional utility [50]. This fits to the classic motive of luxury

usage as “buying to impress others” [43-44]. The premium price is supposed to be only affordable for

successful and elitist people [18]. This link is also proposed by the Veblen effect [48], which state a

higher demand of products with a rising price. Veblen’s argues, that members of a higher class

consume conspicuously to distinguish themselves from the lower class, while members of the lower

class buy conspicuous brands, because they want to be associated with the higher class [18]. But

price is not the only reason, why consumer desire status brand. Brands and their meaning can be

used as signal for one’s identity [51,18].

The uniqueness dimension is based on the assumption that perceived exclusivity and rarity makes

brands more interesting and desirable, and that this effect is even higher when the brand is also

perceived as expensive [50]. It is suggested that uniqueness enhance the self-image and social image

of the user by signaling one’s personal and special taste, or breaking the rules, or avoiding similar

consumption [50]. This dimension is underlined by the snob effect [28], which suggests a declining

consumer demand with a rising number of customers.

The quality dimension is based on the expectation that luxury brands offer superior product

qualities and performance in comparison to non-luxury brands. Consumers may perceive a luxury

brand as more valuable because they may assume greater quality and reassurance [50,1]. Superior

quality is almost always taken for granted for luxury-brand products. Consumers look for the prestige

and premium price of luxury products, expecting that they have a better quality than non-luxury brands

[44].

The hedonism dimension is based on the assumption that hedonism is an important factor of

luxury. Hedonic consumers are looking more for emotional benefits and intrinsic pleasure than for

functionality [50]. Vigneron and Johnson [49] state that consumers with a strong personal orientation

focus on self-directed pleasure from luxury-brand products. They don’t care so much about signaling

effects on peers or social groups by consuming a products or brand.

The extended self dimension is based on the assumption that consumers are integrating the

symbolic meaning into their own identity [50]. Levy [29] describes this dimension perfectly by the

quote: “People buy products not only for what they can do, but also for what they mean”. Consumers

use luxury brands to classify or distinguish themselves in relation to relevant others. This dimension

represents the desire to conform to affluent lifestyles and/or to be distinguished from non-affluent

lifestyles affects their luxury-seeking behavior, but for personal reasons, not for social reasons [50].

1.2.2 Central Concepts of Social Media

Social media and engagement of customers is getting increasingly more attention in theory and by

managers of luxury brands and non luxury brands as well [38,11].

Social media in general can be described as “a group of internet-based applications that build on the

ideological and technological foundations of web 2.0, and that allow the creation and exchange of

User Generated Content” [22]. Some of the most prominent forms of social media are social

networking sites like Facebook. Social networking sites are defined as “web-based services that allow

individuals to construct a public or semi-public profile within a bounded system, articulate a list of other

users with whom they share a connection, and view and traverse their list of connections and those

made by others within the system” [8]. Users with profiles interlinked in this manner are called

“friends.” Theses profiles can include anything from favorite food and movies to relationship statuses

and especially preferences for particular brands, organizations, or celebrities. For example, users can

post information about themselves, post links of websites they like, comment on postings of their

friends, post pictures, and accept invitations for events; they also can receive invitations to become

fans of particular brands, organizations, or celebrities [40]. Today, almost all major social media sites

offer luxury brands as well as normal brands specialized web pages (i.e., fan pages on Facebook;

24.04.12 – 08:42 Jahn_Kunz_Meyer_Luxusmarken_Burmann_König_Final.docx Seite 4 von 13

channels on YouTube; Google+ Pages on Google+) for their communication. These pages are profiles

of organizations, businesses, brands, products, public figures, or causes, and can be used by

companies to integrate and interact with their customer base [9]. Hereby, Social Media platforms like

Facebook offer companies several options for contacting and communicating with their customers. For

instance, fan pages on Facebook are an interesting tool for companies to use. But what does it mean

to become a “fan” of a brand-related page? In general, a fan can be anything from a devotee to an

enthusiast of a particular object. Typical characteristics of fans are self-identification as a fan,

emotional engagement, cultural competence, auxiliary consumption, and co-production [25]. The

Internet has made it possible to overcome geographical restrictions and to build fan communities

worldwide. In practice, users become fans of a Facebook fan page by pressing the "like-button," which

indicates to their social network that they like this brand; this preference is then added to their profiles.

The new content of this fan page is automatically posted to their personal Facebook news feed, and

they can post comments on the fan page, get in contact with the company, forward offers from this

page as well as interact with other fans.

Since brand pages are organized around a single (luxury) brand, product, or company, they can be

seen as a special kind of brand community. Over the last decade, brand communities became very

interested in branding research. Muniz and O’Guinn [32] define a brand community as a “specialized,

non-geographically bound community, based on a structured set of social relationships among

admires of a brand. It is specialized because at its center is a branded good or service. Like other

communities, it is marked by shared consciousness, rituals and traditions, and a sense of moral

responsibility.” [32]. McAlexander and Schouten [31] indicate four crucial relationships in a brand

community: the relationships between the customer and the brand, between the customer and the

firm, between the customer and the product in use, and among fellow customers. Algesheimer and

colleagues [4], using survey data from a European auto club, showed that community identification

leads to positive (i.e. community engagement and community loyalty) and negative (i.e. normative

community pressure and reactance) consequences. Further, they showed an effect of membership

continuance intentions to brand loyalty intentions. Woisetschläger et al. [52] support their results.

Additionally, they found two further reasons for consumer participation in brand communities:

community satisfaction and degree of consumer influence within the community. Moreover, they

showed an effect from community participation on word-of-mouth, brand image, and community

loyalty. An effect on brand loyalty was not shown. By means of data from an online community, Kim et

al. [24] showed that online community commitment is a driver on brand commitment. They also

showed that online community participants possess stronger brand commitment than consumers who

are not members of the community. Recently, Adjei [3] verified in a netnography and experimental

approach that online brand communities are successful tools for increasing sales and showed that the

sharing of information significantly moderates this effect.

Despite the similarities of brand pages with brand communities, they are still different. Brand pages

like fan pages on Facebook or Twitter differ from brand communities by the way they are embedded in

an organic grown and not brand related network of social ties. Thus, members of a brand page are

also connected within the social network site to so called “friends” who might not be “fans” of the brand

and are mostly real offline connections [8]. Given this brand page usage are based on motivations

different from participation in traditional brand communities. Therefore, we look into the literature about

social networking sites. A central topic in studies towards social networking sites is the motivation of

why people use these platforms. For instance, Raacke and Bonds-Raacke [40] found two main

reasons for this: social connections (i.e., keeping in touch with friends) and information sharing (e.g.,

events or gossip). In a similar fashion, Foster and colleagues [15] found one of the main motivations

for participating in social networking sites is the perceived information value from the community and

the connection to friends. Many studies also show that entertainment plays an important role as

shared and consumed content on social networking sites [42,27]. Additionally, Tufekci [45] found that

many activities on social networking sites can also be conceptualized as forms of self-presentation.

Users present themselves by adjusting their profiles, linking to particular friends, displaying their likes

and dislikes, and joining groups. This motivation for social networking usage is supported by several

other studies [9,6,2]. In particular, Peluchette [37] shows that Facebook users employ their postings

24.04.12 – 08:42 Jahn_Kunz_Meyer_Luxusmarken_Burmann_König_Final.docx Seite 5 von 13

consciously to portray images about themselves. Considering the existing research on social

networking sites, we believe there are three main motivation areas for consumers’ using social

networking sites. The first is a relationship area, where the focus of the individual is to stay connected

and interact with others and participate in a social (online) life. The second area is content acquisition

and distribution based on the individuals’ interests. This content can be functional as well as hedonic.

Finally, the third area is self-presentation, which is related to the social context but also serves more

the purpose of self-assurance and personal identity.

But brand pages don’t just differ from brand communities because they are embedded in an organic

grown network. Another important difference is the fact, that brand pages are mainly company driven

and used as an explicit brand communication and interaction channel. In a classical brand community

the brand is the center of the community and the community is “based on a structured set of social

relationships among admires of a brand” [32]. In contrast, a brand page is supposed to be first of all a

connection between the user and the brand.

Despite the popularity in the business practice, only very little empirical research studies consider

brand pages in a branding context. Borle and colleagues [7,10] examined the degree to which

participating on a Facebook fan page affects customer behaviors. In a longitudinal study, conducted in

cooperation with two restaurants, they showed an effect of membership on the fan page to behavioral

loyalty, spending in the restaurants, and the restaurant category over all. The findings support the idea

that Facebook fan pages are useful for deepening the relationship with customers. But it is still not

clear what is happening inside of the “black box” brand page and what the crucial constructs are for

managing brand pages. Empirical studies for brand pages of luxury brands do not exist so far.

1.3 LUXURY BRANDS AND SOCIAL MEDIA

The central question of this article is whether or not social media work for luxury brands. Therefore,

this article now derives various influence areas where social media can increase the luxury brand

perception (see figure 1.2).

Platzhalter Abbildung Start

Figure 1.2 Influential areas of social media brand pages on luxury brands

Quellenangaben: [Urheberrecht beim Autor]

Datei: figure1_2.jpg

24.04.12 – 08:42 Jahn_Kunz_Meyer_Luxusmarken_Burmann_König_Final.docx Seite 6 von 13

Platzhalter Abbildung Stop

As discussed, one important motive of social media usage is self presentation [45]. This motive is

connected with the conspicuousness dimension of luxury. All friends of the fan can see the

membership in the brand page community. So he can show, which brand he identifies with or wants to

be associated with. Because of this overlap of motives, there should be a positive correlation between

brand page usage and conspicuousness as luxury motive.

In contrast to this, we don’t see a positive correlation between social media usage of a brand page

and the need for uniqueness. Brand pages generally have a huge number of fans, even more than the

brand real customers, the perception of being a fan or user of a unique, elitist brand, will suffer under

the enormous number of members, especially when members are behaving inadequately.

We also expect a correlation referring the quality perceptions of a luxury brand. Because members of

virtual brand channels can’t experience the real product on the platform, they may take the quality of

the content and the conversation and interaction on the brand page as a proxy for the quality of the

product. The brand can manage the perception of quality by providing interesting and functional

content and moderate the interaction between the members of a brand page. If a company maintains

its brand page as a communication and interaction channel, it should have a positive effect on the

perception of quality of the brand itself.

This brings us to the hedonic dimension. Usually brand pages are not just functional, but even

hedonic. Brands can provide hedonic, entertaining content, which makes the page more vivid and let

the user experience the brand. This can happen through pictures, videos or music. But even more

interesting is the possibility to interact with the brand as a person. Members can ask questions and get

answers. In other words: The brand is getting alive, which isn’t possible in classic media channels as

advertisement or even web pages.

Finally, we see a correlation with the extended self-perception of luxury. A membership in a brand

community related to a brand page is not just an option to signal the user’s identity, but also a way to

extend their own self by a relationship or “friendship” to a brand. The use and even more the

engagement, participation and interaction on a brand page with the brand and other brand page

members is a way to connect their own personality with a brand’s personality, which represents the

ideal self. Therefore we propose a positive correlation.

Overall, we can conclude that with exception of the uniqueness dimension, social media should have

a positive influence on luxury perception. This fits to Tynan, McKechnie and Chhuon [46], who

accentuate the relevance of co-creating value for luxury brands. That means, luxury brands become

much more than just products, they become are vivid partner for life.

1.4 A FRAMEWORK FOR BRAND PAGE

PARTICIPATION

Considering the relevance of social media brand pages for luxury brands we developed a general

framework (see figure 1.3), which should be valuable not only for luxury brands, but even for

celebrities, television shows, sport teams or music groups (see figure 1, Jahn & Kunz 2012). The

framework is based on classical concepts of uses and gratifications theory [23], customer engagement

[47,19], and involvement theory [53]. By this, we follow a basic approach, describing how brand page

participation might influence consumers’ brand loyalty and what might influence the brand page

behavior itself. For this, we divide the process into three zones: gratification, participation, and

customer-brand relationship. The basic idea of this framework is that, if the brand brand page satisfies

particular needs of a user, this satisfaction should lead to a higher approach to the brand page, which

should in turn lead to a higher brand loyalty.

The uses and gratification (U&G) theory, proposed by Katz [23] , has been found useful for application

to new media like the internet, online communities, social networking, and blogs. U&G theory tries to

24.04.12 – 08:42 Jahn_Kunz_Meyer_Luxusmarken_Burmann_König_Final.docx Seite 7 von 13

explain why individuals have different media-usage patterns. According to U&G theory, people use

media to satisfy various needs and to achieve their goals. The most prominent needs can be

subsumed into three areas: A content-oriented area based on the information delivered by the media,

a relationship-oriented area based on social interaction with others, and a self-oriented area based on

particular needs of individuals such as achieving status or need for diversion. We take these

categories, which perfectly fit with the luxury relevant dimensions, as central motives for brand page

participation. With the second concept, consumer engagement, we want to differentiate the media

consumption of a brand page. The customer relationship literature shows that customer behavior goes

“beyond transaction, and may be specifically defined as a customer’s behavioral manifestation that

has a brand or firm focus, beyond purchase, resulting from motivational drivers” [47].

Transferring the engagement construct to the context of a brand page, we define brand page

engagement as an interactive and integrative participation in the brand page community and would

differentiate this from the solely usage intensity of a member. We do not expect these constructs to be

independent from each other and would assume that brand page usage leads to brand page

engagement. For instance, it is possible that a person is using a brand page on a regular basis (e.g.,

receiving gratis coupons from the brand page) without becoming highly engaged with the brand page.

Platzhalter Abbildung Start

Figure 1.3 Framework of brand page participation

Quellenangaben: [Urheberrecht beim Autor]

Datei: figure1_3.jpg

Platzhalter Abbildung Stop

To explain the brand page usage behavior, we use the three gratification areas of U&G theory

introduced above, and we apply them according to the context of the brand pages. In the content area,

we differentiate between the functional and hedonic values that are delivered. In the relationship area,

we see two main kinds of relationships where an interaction could be of value for a brand page user:

24.04.12 – 08:42 Jahn_Kunz_Meyer_Luxusmarken_Burmann_König_Final.docx Seite 8 von 13

The interaction with other users, and the interaction with the brand or company behind the brand.

Finally, consumers can decide to participate in a brand page because they expect an impact on their

image or status. In this case, consumers defer values for their own personal identities by being

members of a brand page.

After considering the value and brand page behavior, we wanted to give some reasons for the

expected relationship to branding. The central concept for brand relationship in our model is brand

loyalty. Oliver defines loyalty as “a deeply held commitment to rebuy or re-patronize a preferred

product/service consistently in the future, thereby causing repetitive same-brand or same brand-set

purchase, despite situational influences and marketing efforts having the potential to cause switching

behavior” [35]. This definition stresses the importance of two important components: an attitudinal (i.e.

commitment) and a behavioral (i.e. purchase, patronage) component of loyalty.

On the one hand, brand page users that show high usage intensity, get in regular contact with the

brand, which in turn should have an effect on their brand relationship and should increase their

likelihood for repurchase, word-of-mouth, or their general commitment to the brand. On the other side,

brands with high brand page engagement already have developed a strong relationship to the brand

page community. This emotional bond is also associated with the object of the brand page, the brand.

Thus, we assume that an increase in brand loyalty is based on brand page engagement. This

relationship is also supported by the involvement theory. Involvement can be defined as “a person’s

perceived relevance of the object based on inherent needs, values, and interests.” [53]. Brand page

usage and engagement are indicators for a high involvement with the brand.

1.5 EMPIRICAL RESULTS OF CONSUMER

PARTICIPATION ON BRAND PAGES

Platzhalter Abbildung Start

Figure 1.4 : Framework of brand page participation

Quellenangaben: [Urheberrecht beim Autor]

Datei: figure1_4.jpg

24.04.12 – 08:42 Jahn_Kunz_Meyer_Luxusmarken_Burmann_König_Final.docx Seite 9 von 13

Platzhalter Abbildung Stop

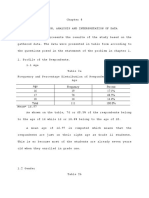

To test our framework in a field environment, we executed a survey on Facebook. For the data

collection, we invited members of different luxury and non-luxury brand fan pages (e.g. Audi, BMW,

HTC, L’Oréal, Lufthansa) to participate in an online survey by posting the survey link on the fan page.

Through the survey, we obtained a sample of 523 fully completed questionnaires of brand page

members. Gender is distributed evenly in the sample (51.7 % female, 48.3% male). Average age of

the respondents was 28.6. All participants were frequent brand page users (more than 80% use their

brand pages at least once a week) and active Facebook members (76% use Facebook longer than 20

minutes a day). For the constructs of our framework, we generated multi-item scales on the basis of

previous measures, the qualitative pre-studies, and the theoretical foundation. The reliability results of

the constructs indicate acceptable psychometric properties for all constructs.

We tested the proposed hypotheses using a structural equation model. The fit statistics indicate an

adequate fit of the proposed model (i.e. χ2/df= 2.99; CFI= .92; RMSEA= .062). The results of the

model estimation are shown in figure 1.4.

The multiple squared correlations for brand loyalty are .28, which is reasonable considering that online

brand pages are not the online influence factor for the consumer-brand relationship. All coefficients of

our proposed processing model (except two) were highly significant (p< .001). We haven’t found a

significant effect from the social interaction value to brand page usage. This might be because social

interaction mainly focuses on elements related to membership exchange. By means of passive

consumption of a media, social interaction value can hardly be gained. The effect from brand

interaction value on brand page engagement is just significant on the 0.01 level.

1.6 SOME IMPLICATIONS FOR SOCIAL MEDIA OF

LUXURY BRANDS

In summary, we can infer multiple implications for the management of social media brand pages of

usual and luxury brands. First of all, we can conclude that brand pages are an excellent tool for brand

management today: They have measurable effects on the customer brand relationship. Brand

managers should embrace this new channel and understand how to work with it in a contemporary

fashion. Setting up a brand page and generating pure traffic data (e.g., visits) is not enough to improve

customer relationships. The goal of a brand page strategy is to completely engage, integrate, and

immerse users in a vivid and active community. Therefore, luxury brand companies need to give users

realistic reasons to engage in a brand page community. This can be done for example by customer

integration in the designing process of a new fashion collection, a model competition for a new media

campaign, exclusive and preview offers to the fan community, invitations to exclusive events or

consumer surveys about new trends.

A second value driver is based on interaction among brand page members and between customers

and the brand itself. Luxury brand companies should therefore create as much interactivity as

possible. The critical factor is not the amount of fans but the level of interaction. The luxury fashion

label Burberry for example has almost 11 million fans as members of their brand page, but the

dialogue between fans as well as the company seems not very intensive. But if the company is not

(inter)active, their brand pages will not be successful because brand pages are interactive channels.

Also luxury brands are co-creative and can provide more experience through an active integration of

and interaction with the consumers. Online events or exclusive videos for example can trigger

discussions about relevant topics. Beyond consumer interactivity, companies must scan brand pages

and be attentive to the happenings in their brand page communities. They must answer questions

immediately and communicate proactively, even more so when comments are negative (Kunz,

Munzel, & Jahn 2012). Beside the interaction between the brand and the consumer it’s very important

to moderate the ongoing fan interaction. When fans act inadequately they can ruin the special image

of a brand within seconds. This is especially important for luxury brands, because user perceive to be

elitist, exclusive and special. But in social media everybody can become fan of a luxury brand like

24.04.12 – 08:42 Jahn_Kunz_Meyer_Luxusmarken_Burmann_König_Final.docx Seite 10 von 13

Aston Martin. This may cause problems, because there will be a mixture of different social groups,

interacting together on one platform.

Finally, from our empirical results, we see that valuable content, both hedonic and functional, on the

brand page itself is one of the most important drivers for attracting users to brand pages. Brand pages

must deliver interesting, entertaining, and innovative content to its fans. Luxury brands have to be

aware that the content fits to the exclusive character of the brand and doesn’t destroy the elitist image

of the brand. It is especially important to avoid the image of a mass-market brand. Therefore, the

content should be unique to underline the experience of a luxury brand as something special such as

extensive HD-videos, special presentations of the product or brand, interviews with testimonials,

statements of the CEO or exclusive pictures of brand related or sponsored events. It must be noted

that sweepstakes should not be included in the valuable content as you can find sweepstakes on

every brand page and sweepstakes do not fit to an exclusive and elitist image of a brand.

The mixture of social and commercial aspects makes brand pages unique. Our study has shown there

is high potential of brand pages for the customer/brand relationship. Ideally, fans would see brands as

real “friends” in their social networks, which plays an important part in their everyday lives. In this

case, brand communication is no longer automatically perceived as disturbing advertising but as

interesting and reasonable. If luxury brand companies understand the reasons for brand page usage

and engagement, they can use this to interact with, integrate, and engage their customers as well as

transform them from ordinary users to real “fans” of their brands. Social Media is a huge chance for

luxury branding, but companies have to realize that brand pages are not just a further communication

channel; they are a real interaction channel. This fact provides various opportunities for brand

communication, but is still a challenge for companies that are not used to social media and the new

power of their consumers.

1.7 Literaturverzeichnis

1. Aaker, D. (1991). Managing Brand Equity: Capitalizing on the Value of a Brand Name. New York: Free Press.

2. Acquisti, A., & Gross, R. Imagined Communities: Awareness, Information Sharing, and Privacy on the Facebook. In B.

Springer (Hrsg.), International Workshop on Privacy Enhancing Technologies, Cambridge, UK, 2006 (S. 1-16)

3. Adjei, M. T., Noble, S. M., & Noble, C. H. (2010). The Influence of C2C Communications in Online Brand Communities on

Customer Purchase Behavior. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 38(5), 634-653.

4. Algesheimer, R., Dholakia, U., & Herrmann, A. (2005). The Social Influence of Brand Community: Evidence from European

Car Clubs. Journal of Marketing, 69(3), 19-34.

5. Berry, C. J. (1994). Idea of Luxury: A Conceptual and Historical Investigation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

6. Bolar, K. P. (2009). Motives Behind the Use of Social Networking Sites: An Empirical Study. ICFAI Journal of Management

Research, 8(1), 75-84.

7. Borle, S., Dholakia, U., Singh, S., & Durham, E. (2010). An Empirical Investigation of the Impact of Facebook Fan Page

Participation on Customer Behavior. Rice University, Houston.

8. Boyd, D. M., & Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scolarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated

Communication, 13(1),

9. Dholakia, U. M., Bagozzi, R. P., & Pearo, L. K. (2004). A Social Influence Model of Consumer Participation in Network- and

Small-Group-Based Virtual Communities. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 21(3), 241-263,

doi:10.1016/j.ijresmar.2003.12.004.

10. Dholakia, U. M., & Durham, E. (2010). One Café Chain's Facebook Experiment. Harvard Business Review, 88(3), 26-26.

11. Donaldson, M. S. (2011). Promoting Luxury Goods in China through Social Media. MultiLingual(October/November), 29-31.

12. Dubois, B., & Duquesne, P. (1993). The Market for Luxury Goods: Income versus Culture. European Journal of Marketing,

27(1), 35-44.

13. Dubois, B., & Duquesne, P. (1993). Polarization Maps: A new Approach to Identifying and Assessing Competitive Position -

The Case of Luxury Brands. Marketing and Research Today, 21(May), 115-123.

14. Dubois, B., Laurent, G., & Czellar, S. (2001). Consumer Rapport to Luxury: Analyzing Complex and Ambivalent Attitudes.

Consumer Research Working Paper. Jouy-en-Josas: HEC.

15. Foster, M. K., Francescucci, A., & West, B. C. (2010). Why Users Participate in Online Social Networks. International

Journal of e-Business Management, 4(1), 3-19.

16. Geerts, A., & Veg-Sala, N. (2011). Evidence on Internet Communication - Management Strategies for Luxury Brands. Global

Journal of Business Research, 5(5), 81-94.

17. Grossman, G. M., & Shapiro, C. (1988). Foreign Counterfeiting of Status Goods. The Quaterly Journal of Economics,

24.04.12 – 08:42 Jahn_Kunz_Meyer_Luxusmarken_Burmann_König_Final.docx Seite 11 von 13

103(1), 79-100.

18. Han, Y. J., Nunes, J. C., & Drèze, X. (2010). Signaling Status with Luxury Goods: The Role of Brand Prominence. Journal of

Marketing, 74(4), 15-30.

19. Hennig-Thurau, T., Malthouse, E. C., Friege, C., Gensler, S., Lobschat, L., Rangaswamy, A., et al. (2010). The Impact of

New Media on Customer Relationships. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 311-330.

20. Kapferer, J.-N. (1997). Managing Luxury Brands. Journal of Brand Management, 4(4), 251-260.

21. Kapferer, J.-N. (1998). Why are we seduced by Luxury Brands. Journal of Brand Management, 6(1), 44-49.

22. Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the World, Unite! The Challenges and Opportunities of Social Media.

Business Horizons, 53, 59-68.

23. Katz, E. (1959). Mass Communication Research and the Study of Culture. Studies in Public Communication, 2, 1-6.

24. Kim, J. W., Choi, J., Qualls, W., & Kyesook, H. (2008). It Takes a Marketplace Community to Raise Brand Commitment: The

Role of Online Communities. Journal of Marketing Management, 24(3), 409-431.

25. Kozinets, R. V., de Valck, K., Wojnicki, A. C., & Wilner, S. J. S. (2010). Networked Narratives: Understanding Word-of-Mouth

Marketing in Online Communities. Journal of Marketing, 74(2), 71-89.

26. Langmack, F. (2006). Premiummarken - Begriffsbestimmung, Typologisierung und Implikationen für das Management.

München: FGM Verlag.

27. LaRose, R., Mastro, D., & Eastin, M. S. (2001). Understanding Internet Usage. Social Sciences Computer Review, 19(4),

395-413.

28. Leibenstein, H. (1950). Bandwagon, Snob, and Veblen Effects in the Theory of Consumers' Demand. Quarterly Journal of

Economics, 64(2), 183-207.

29. Levy, S. J. (1959). Symbols for Sale. Harvard Business Review, 37(4), 117-124.

30. Libai, B., Bolton, R., Bügel, M. S., de Ruyter, K., Götz, O., Risselada, H., et al. (2010). Customer-to-Customer Interactions:

Broadening the Scope of Word of Mouth Research. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 267-282,

doi:10.1177/1094670510375600.

31. McAlexander, J., Schouten, J., & Koenig, H. (2002). Building Brand Community. Journal of Marketing, 66(1), 38-54.

32. Muniz Jr, A. M., & O'Guinn, T. C. (2001). Brand Community. [Article]. Journal of Consumer Research, 27(4), 412-432.

33. Nueno, J. L., & Quelch, J. A. (1998). The Mass Marketing of Luxury. Business Horizons, November-December, 61-68.

34. Okonkwo, U. (2009). Sustaining the Luxury Brand on the Internet. Journal of Brand Management, 16(5/6), 302-310.

35. Oliver, R. L. (1999). Whence Consumer Loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 63(4), 33-44.

36. Oxford Latin Dictionary (1992). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

37. Peluchette, J., & Karl, K. (2009). Examining Students’ Intended Image on Facebook: “What Were They Thinking?!”. The

Journal of Education for Business, 85(1), 30-37, doi:10.1080/08832320903217606.

38. Phan, M. (2011). Do Social Media Enhance Consumer's Perception and Purchase Intentions of Luxury Brands? VIKALPA,

36(1), 81-84.

39. Phau, I., & Prendergast, G. (2000). Consuming Luxury Brands: The Relevance of the "Rarity Principle". Journal of Brand

Management, 8(2), 122-138.

40. Raacke, J., & Bonds-Raacke, J. B. (2008). MySpace and Facebook: Applying the Uses and Gratifications Theory to

Exploring Friend-Networking Sites. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 11(2), 169-174.

41. Sekora, J. (1977). Luxury: The Concept in Western Thought - Eden to Smollet. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University

Press.

42. Sheldon, P. (2008). The Relationship Between Unwillingness-to-Communicate and Students’ Facebook Use. Journal of

Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Applications, 20(2), 67-75.

43. Truong, Y. (2010). Personal Aspirations and the Consumption of Luxury Goods. International Journal of Market Research,

52(5), 653-671.

44. Tsai, S.-p. (2005). Impact of Personal Orientation on Luxury-Brand Purchase Value. International Journal of Market

Research, 47(4), 429-454.

45. Tufekci, Z. (2008). Grooming, Gossip, Facebook and Myspace. Info., Comm. & Soc., 11(4), 544-564,

doi:10.1080/13691180801999050.

46. Tynan, C., McKechnie, S., & Chhuon, C. (2010). Co-Creating Value for Luxury Brands. Journal of Business Research, 63,

1156-1163.

47. van Doorn, J., Lemon, K., Mittal, V., Nass, S., Pick, D., Pirner, P., et al. (2010). Customer Engagement Behavior:

Theoretical Foundations and Research Directions. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 253-266.

48. Veblen, T. (1899). The Theory of the Leisure Class. New York: Penguin.

49. Vigneron, F., & Johnson, L. W. (1999). A Review and a Conceptual Framework of Prestige Seeking Consumer Behavior.

Journal of the Academy of Market Science Review(1).

50. Vigneron, F., & Johnson, L. W. (2004). Measuring Perceptions of Brand Luxury. Brand Management, 2(6), 484-506.

51. Wernerfelt, B. (1990). Advertising Content - When Brand Choice is a Signal. Journal of Business, 63(1), 91-98.

52. Woisetschläger, D. M., Hartleb, V., & Blut, M. (2008). How to Make Brand Communities Work: Antecedents and

Consequences of Consumer Participation. Journal of Relationship Marketing, 7(3), 237-256,

24.04.12 – 08:42 Jahn_Kunz_Meyer_Luxusmarken_Burmann_König_Final.docx Seite 12 von 13

doi:10.1080/15332660802409605.

53. Zaichkowsky, J. L. (1985). Measuring the Involvement Construct. Journal of Consumer Research, 12(3), 341-352.

24.04.12 – 08:42 Jahn_Kunz_Meyer_Luxusmarken_Burmann_König_Final.docx Seite 13 von 13

You might also like

- Customer EngagementDocument14 pagesCustomer Engagementkash811No ratings yet

- Thesis Guideline UumDocument50 pagesThesis Guideline UumAbdelMoumen BenchabaneNo ratings yet

- A Guide To APA Referencing Style: 6 EditionDocument35 pagesA Guide To APA Referencing Style: 6 EditionOrji Somto K100% (3)

- Chapter One: Creating Customer Value and EngagementDocument36 pagesChapter One: Creating Customer Value and Engagementkash811No ratings yet

- Al Ries & Jack Trout - The 22 Immutable Laws of BrandingDocument8 pagesAl Ries & Jack Trout - The 22 Immutable Laws of BrandingDana IvanNo ratings yet

- Theory: University BrandingDocument4 pagesTheory: University Brandingkash811No ratings yet

- Modeling Customer Loyalty From An Integrative Perspective of Self-Determination Theory and Expectation-Confirmation TheoryDocument12 pagesModeling Customer Loyalty From An Integrative Perspective of Self-Determination Theory and Expectation-Confirmation Theorykash811No ratings yet

- The Value of Brand EquityDocument7 pagesThe Value of Brand Equitykash81150% (4)

- Customer Loyalty and Switching Cost in TurkeyDocument15 pagesCustomer Loyalty and Switching Cost in Turkeyjawaria73100% (1)

- President criticized over flood responseDocument2 pagesPresident criticized over flood responsekash811No ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Cise 1Document52 pagesCise 1AkankshaNo ratings yet

- Us Visa Application Form: Choose OneDocument4 pagesUs Visa Application Form: Choose OneGladys MalekarNo ratings yet

- Mba 1Document33 pagesMba 1Hrithik ChaurasiaNo ratings yet

- Madhya Pradesh Tourism - Case StudyDocument9 pagesMadhya Pradesh Tourism - Case StudyAnonymous E5QFMDjVKNo ratings yet

- Social Media and Its Impact in Marketing Strategy PDFDocument7 pagesSocial Media and Its Impact in Marketing Strategy PDFrankiadNo ratings yet

- Social Commerce A Paradigm Shift in E-CommerceDocument8 pagesSocial Commerce A Paradigm Shift in E-CommercearcherselevatorsNo ratings yet

- Social Media Marketing for HealthcareDocument19 pagesSocial Media Marketing for HealthcareTushar JadhavNo ratings yet

- Social Media Policy - HCL TechnologiesDocument17 pagesSocial Media Policy - HCL TechnologiesPrince kalraNo ratings yet

- FindLaw Social Media For Attorneys MiniguideDocument14 pagesFindLaw Social Media For Attorneys MiniguideFindLaw100% (2)

- Google search page settingsDocument10 pagesGoogle search page settingsdm123caldasNo ratings yet

- By The Authors Students of Novaliches High SchoolDocument26 pagesBy The Authors Students of Novaliches High SchoolKristianKurtRicaroNo ratings yet

- 51 Winning Website Traffic IdeasDocument9 pages51 Winning Website Traffic IdeasStarkmendNo ratings yet

- L T P/ S SW/F W Total Credit UnitsDocument4 pagesL T P/ S SW/F W Total Credit UnitsRamuNo ratings yet

- Social Networking Sites: by Nidhi VatsDocument23 pagesSocial Networking Sites: by Nidhi VatsAkashNo ratings yet

- Social Media AnalyticsDocument8 pagesSocial Media AnalyticsAnjum ZafarNo ratings yet

- ICT Project MaintenanceDocument12 pagesICT Project MaintenanceZhaine Venneth BiaresNo ratings yet

- Media Use in The Middle East: An Eight-Nation Survey - NU-QDocument30 pagesMedia Use in The Middle East: An Eight-Nation Survey - NU-QOmar ChatriwalaNo ratings yet

- HackYourFriend PDFDocument7 pagesHackYourFriend PDFFarhan AzaNo ratings yet

- Social Media Tune UpDocument31 pagesSocial Media Tune UpTran Minh TriNo ratings yet

- What Happens to Man After Death According to the BibleDocument18 pagesWhat Happens to Man After Death According to the BibleNana TweneboahNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4Document16 pagesChapter 4Hazel Norberte SurbidaNo ratings yet

- Tasks - TechnologyDocument19 pagesTasks - Technologysurendra tupeNo ratings yet

- Social Media Image Sizes 2017 A4 Print ReadyDocument12 pagesSocial Media Image Sizes 2017 A4 Print ReadyCarlos PáramoNo ratings yet

- Impact of Social Media Over Luxury BrandsDocument70 pagesImpact of Social Media Over Luxury BrandsPatyFreeNo ratings yet

- First Namelast Name Title Company: Rudri LTD Chief Executive Officer C-LevelDocument12 pagesFirst Namelast Name Title Company: Rudri LTD Chief Executive Officer C-LevelkhanmujahedNo ratings yet

- Matching Quotes: Home Authors Topics Quote of The Day Pictures Sign UpDocument57 pagesMatching Quotes: Home Authors Topics Quote of The Day Pictures Sign UpAmanKumarNo ratings yet

- 501 SyllabusDocument13 pages501 SyllabusmrdeisslerNo ratings yet

- The Beginners Guide To Social MediaDocument71 pagesThe Beginners Guide To Social MediaNicole MalfattoNo ratings yet

- VR SopDocument8 pagesVR Sopold manNo ratings yet