Professional Documents

Culture Documents

ACEAGRO

Uploaded by

Janine OlivaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

ACEAGRO

Uploaded by

Janine OlivaCopyright:

Available Formats

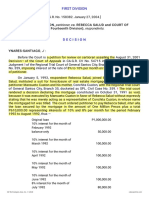

Ace-Agro Development Corp.

vs CA

FACTS:

Ace-Agro had been cleaning soft drink bottles and repairing wooden shells for Cosmos within

its company premises in San Fernando, Pampanga. On April 25, 1990, a fire broke out in the Cosmos plant.

As a result, Ace-Agro’s work stopped. On May 15, 1990, Ace-Agro requested Cosmos to resume its services

but they were advised that on account of the fire destroying nearly all the bottles and shells, Cosmos was

terminating their contract.

Ace-Agro requested Cosmos to reconsider its decision but upon receiving no reply, they

informed the employees of the termination of their employment, which led the employees to file a

complaint for illegal dismissal before the Labor Arbiter against both Ace-Agro and Cosmos. Ace-Agro sent

another letter for reconsideration to Cosmos to which they replied that they could resume work

but outside company premises. Ace-Agro refused the offer, claiming that to work outside would

incur additional transportation costs. Cosmos then advised Ace-Agro that they could resume work inside

the company premises but then Ace-Agro unjustifiably refused because it wanted and extension of the

contract to make up for the period of inactivity.

ISSUE:

Whether or not the period during which work has been suspended brought by force majeure justifies an

extension of the term of the contract?

HELD:

No. The suspension of work due to fire does not merit an automatic extension. The stipulation

that in the event of a fortuitous event or force majeure the contract shall be deemed suspended during

the said period does not mean that it stops the running of the period the contract has been agreed upon

to run. The fact that the contract is subject to a resolutory period, which relieves the parties of their

respective obligations, does not stop the running of the period of their contract

Furthermore, the contract between petitioner and private respondent did not prohibit the

hiring by private respondent of another service contractor. With private respondent hitting production at

8,000 bottles of soft drinks per day, petitioner could clearly not handle the business, since it could clean

only 2,500 bottles a day. These facts show that although Aren Enterprises' rate was lower than

petitioner's, they did not affect private respondent's business relation with petitioner.

Despite private respondent's contract with Aren Enterprises, private respondent continued

doing business with petitioner and would probably have done so were it not for the fire. On the other

hand, Aren Enterprises could not be begrudged for being allowed to continue rendering service even after

the fire because it was doing its work outside private respondent's plant. For that matter, after the fire,

private respondent on August 28, 1990 offered to let petitioner resume its service provided this was done

outside the plant.

Petitioner may not be to blame for the failure to resume work after the fire, but neither is

private respondent. Since the question is whether private respondent is guilty of breach of contract, the

fact that private respondent is blameless can only lead to the conclusion that the appealed decision is

correct.

Petition denied. Court of Appeals affirmed.

You might also like

- Design 6: Proposed Art Museum ConversionDocument1 pageDesign 6: Proposed Art Museum ConversionJanine OlivaNo ratings yet

- PPL V Perez DigestDocument2 pagesPPL V Perez DigestJanine Oliva100% (1)

- Design 6 - Propose 5-Star Luxury HotelDocument1 pageDesign 6 - Propose 5-Star Luxury HotelJanine OlivaNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law II Midterm CoverageDocument4 pagesConstitutional Law II Midterm CoverageJanine OlivaNo ratings yet

- Raul Sesbreño, Petitioner, vs. Hon. Court of Appeals, Delta Motors Corporation and Pilipinas BankDocument18 pagesRaul Sesbreño, Petitioner, vs. Hon. Court of Appeals, Delta Motors Corporation and Pilipinas BankNetweightNo ratings yet

- Gonzales Vs CabucanaDocument1 pageGonzales Vs CabucanaJanine OlivaNo ratings yet

- SC Rules Art 1332 Inapplicable in Land Ownership CaseDocument3 pagesSC Rules Art 1332 Inapplicable in Land Ownership CaseJanine OlivaNo ratings yet

- Consti 2Document6 pagesConsti 2Janine OlivaNo ratings yet

- 19 Asiain v. JalandoniDocument1 page19 Asiain v. JalandoniJanine OlivaNo ratings yet

- Consti 2Document7 pagesConsti 2Janine OlivaNo ratings yet

- Digest 02.14.19Document2 pagesDigest 02.14.19Janine OlivaNo ratings yet

- Consti 2Document6 pagesConsti 2Janine OlivaNo ratings yet

- Petitioner Vs Vs Respondents: First DivisionDocument5 pagesPetitioner Vs Vs Respondents: First DivisionJanine OlivaNo ratings yet

- Petitioner Vs Vs Respondents: First DivisionDocument5 pagesPetitioner Vs Vs Respondents: First DivisionJanine OlivaNo ratings yet

- City of Manila v. Chinese Community of ManilaDocument21 pagesCity of Manila v. Chinese Community of ManilaJanine OlivaNo ratings yet

- Silva Vs CA GR 114742 DigestDocument1 pageSilva Vs CA GR 114742 DigestJanine OlivaNo ratings yet

- Atty Bathan Case Digests on Presumptions and Creditor's RightsDocument2 pagesAtty Bathan Case Digests on Presumptions and Creditor's RightsJanine OlivaNo ratings yet

- Crim LawDocument9 pagesCrim LawJanine OlivaNo ratings yet

- Court Orders Deposit to Prevent Unjust EnrichmentDocument3 pagesCourt Orders Deposit to Prevent Unjust EnrichmentJanine OlivaNo ratings yet

- Busorg Digests (2S, 2012)Document56 pagesBusorg Digests (2S, 2012)Gabby PundavelaNo ratings yet

- La Mallorca Vs CADocument1 pageLa Mallorca Vs CAJanine OlivaNo ratings yet

- SC upholds hierarchy of courts in dismissing directly filed certiorari petitionDocument277 pagesSC upholds hierarchy of courts in dismissing directly filed certiorari petitionKris NageraNo ratings yet

- Court Orders Deposit to Prevent Unjust EnrichmentDocument3 pagesCourt Orders Deposit to Prevent Unjust EnrichmentJanine OlivaNo ratings yet

- Tanguilig Vs CADocument1 pageTanguilig Vs CAJanine OlivaNo ratings yet

- Samson Vs CADocument1 pageSamson Vs CAJanine OlivaNo ratings yet

- Persons Art. 9 - 15Document9 pagesPersons Art. 9 - 15Janine OlivaNo ratings yet

- Bank Pays Late Delivery, Recovers FundsDocument4 pagesBank Pays Late Delivery, Recovers FundsJanine Oliva100% (2)

- LegProf - Tolosa Vs CargoDocument6 pagesLegProf - Tolosa Vs CargoJanine OlivaNo ratings yet

- Recalling, Revoking or Abrogation of A Statute by Another: Repeal, Define DDocument5 pagesRecalling, Revoking or Abrogation of A Statute by Another: Repeal, Define DJanine OlivaNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Adikavi Nannaya University Rajamahendravaram: CBCS/Semester System (W.e.f. 2016-17 Admitted Batch) I Semester SyllabusDocument63 pagesAdikavi Nannaya University Rajamahendravaram: CBCS/Semester System (W.e.f. 2016-17 Admitted Batch) I Semester SyllabusRevanth NarigiriNo ratings yet

- Records: Las Vegas Dentists Were Required To Donate To NonprofitsDocument25 pagesRecords: Las Vegas Dentists Were Required To Donate To NonprofitsLas Vegas Review-JournalNo ratings yet

- LM Power Vs Capitol Industrial DigestDocument3 pagesLM Power Vs Capitol Industrial DigesttinctNo ratings yet

- Department Order No.10 Series of 1997Document13 pagesDepartment Order No.10 Series of 1997Mike E DmNo ratings yet

- Westmont V Francia 661 Scra 787Document16 pagesWestmont V Francia 661 Scra 787Edwin Villegas de NicolasNo ratings yet

- 54 Department of Agriculture V NLRC Case DigestDocument3 pages54 Department of Agriculture V NLRC Case DigestRexNo ratings yet

- Fernandez vs. Torres CaseDocument4 pagesFernandez vs. Torres CaseMary Anne R. BersotoNo ratings yet

- 17.defect Liability Period and Account Closing - en .Wan SaipallahDocument34 pages17.defect Liability Period and Account Closing - en .Wan SaipallaherickyfmNo ratings yet

- Law of Agency NotesDocument7 pagesLaw of Agency NotesCha Eun WooNo ratings yet

- Land Registration Dispute Over LotDocument10 pagesLand Registration Dispute Over LotLyceum LawlibraryNo ratings yet

- Law of PartnershipDocument63 pagesLaw of PartnershipAyieNo ratings yet

- Revisions to the 2016 IRR of RA 9184Document111 pagesRevisions to the 2016 IRR of RA 9184Jonnel AcobaNo ratings yet

- NES 309 Requirements For Gas Turbines Category 2Document79 pagesNES 309 Requirements For Gas Turbines Category 2JEORJENo ratings yet

- Construction Claims & Dispute ResolutionsDocument19 pagesConstruction Claims & Dispute ResolutionsNathan yemane100% (1)

- Pinnacle Port Community Association, Inc. v. Charles Orenstein, 872 F.2d 1536, 11th Cir. (1989)Document16 pagesPinnacle Port Community Association, Inc. v. Charles Orenstein, 872 F.2d 1536, 11th Cir. (1989)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Retainer Contract Between LawyerDocument2 pagesRetainer Contract Between LawyerEarl CalingacionNo ratings yet

- Contract For Use of StudDocument3 pagesContract For Use of StudBuna BunaNo ratings yet

- UST Golden Notes - Administrative LawDocument10 pagesUST Golden Notes - Administrative LawPio Guieb AguilarNo ratings yet

- Duano Book NotesDocument6 pagesDuano Book NotesCherry Jean RomanoNo ratings yet

- The Labor Aspect of Student Internship - ACCRALAW PDFDocument6 pagesThe Labor Aspect of Student Internship - ACCRALAW PDFjune dela cernaNo ratings yet

- Labrel Midterms and FinalsDocument186 pagesLabrel Midterms and Finalsjanine nenariaNo ratings yet

- Defective Incorporation - de Facto Corporations Corporations by EDocument29 pagesDefective Incorporation - de Facto Corporations Corporations by EEl-Seti Anu Ali ElNo ratings yet

- Letter of IntentDocument2 pagesLetter of Intentpierololli75% (4)

- Early Essays on Marriage, Divorce and Women's RightsDocument2 pagesEarly Essays on Marriage, Divorce and Women's RightsRalucaTeodorescuNo ratings yet

- Desmopan 192 ISODocument2 pagesDesmopan 192 ISOaakashlakhanpal9830No ratings yet

- Jurisprudence Survey on Persons and Family RelationsDocument16 pagesJurisprudence Survey on Persons and Family RelationsJoelNo ratings yet

- LAWst How To Write A Case DigestDocument7 pagesLAWst How To Write A Case DigestyazzNo ratings yet

- I. Multiple Choice Questions: C) Solutio IndebitiDocument4 pagesI. Multiple Choice Questions: C) Solutio IndebitiJann Garcia100% (1)

- A Project On A Detailed Study On The Concept of Legal PersonsDocument20 pagesA Project On A Detailed Study On The Concept of Legal PersonsharshalNo ratings yet

- !01192008 ITTs Memo For Record - Report of Fraud To ITTDocument4 pages!01192008 ITTs Memo For Record - Report of Fraud To ITTTrafficked_by_ITTNo ratings yet