Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Identity in Flux: Negotiating Identity While Studying Abroad

Uploaded by

Bella KarinaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Identity in Flux: Negotiating Identity While Studying Abroad

Uploaded by

Bella KarinaCopyright:

Available Formats

531920

research-article2014

JEEXXX10.1177/1053825914531920Journal of Experiential EducationYoung et al.

Article

Journal of Experiential Education

2015, Vol. 38(2) 175–188

Identity in Flux: Negotiating © The Authors 2014

Reprints and permissions:

Identity While Studying sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1053825914531920

Abroad jee.sagepub.com

Jennifer T. Young1, Rajeswari Natrajan-Tyagi2,

and Jason J. Platt3

Abstract

Study abroad is one aspect of global movement that connects individuals of diverse

backgrounds. Individuals studying abroad are proffered to negotiate self-identity

when they confront novelty and new contexts. This study chose to use the qualitative

method of phenomenological interviews to examine how individuals experience

themselves and others when abroad. Specifically, the study focused on modifications

of self-identity via self-images. The results presented emotions, cognitions, and

behaviors experienced by individuals during global encounters. The study indicates

that individuals negotiate identity while studying abroad and modify self-images

associated with personal identity (unique character traits) rather than social identity

(shared traits with ingroup). The authors propose that identity among global citizens

is an ongoing process that is context dependent and less stable than previously

regarded.

Keywords

identity negotiation, study abroad, globalization, global identity

We live in a period of time where our global village is filled with more opportunities

for its diverse inhabitants to interact with one another both in person and via virtual

reality than any time in history. Enhanced telecommunication services, air travel, and

social media outlets have increased the amount of contact individuals have with

1California State University, Long Beach, USA

2Alliant International University, Irvine, CA, USA

3Alliant International University, Mexico City, Mexico

Corresponding Author:

Jennifer T. Young, Psychologist, Counseling and Psychological Services, California State University, 1250

Bellflower Blvd., BH-226, Long Beach, CA 90840, USA.

Email: Jennifer.young@csulb.edu.

Downloaded from jee.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 8, 2016

176 Journal of Experiential Education 38(2)

diverse others and has transformed the individual’s context to a global context

(Hermans & Dimaggio, 2007). The frequency of offshoring and outsourcing business

practices to contractors in foreign countries has highlighted the importance of intercul-

tural competence in employees so that they are equipped to work with diverse cultures

with varying values and belief systems. As such, cultural competence has shifted from

an emphasis on multicultural competence, which focuses on knowledge, skills, and

attitudes when interacting with diverse groups (Sue, Arredondo, & McDavis, 1992), to

intercultural competence, which is defined as a comprehension of cultural differences

and similarities evoking a deeper sense of self-awareness and cultural awareness

(Chen & Starosta, 2000). Consequently, educational institutions are uncovering ways

to better equip their students to become global citizens by promoting study abroad and

other intercultural exchange (King & Magolda, 2005; Miller, Todahl, Platt, Lambert-

Shute, & Eppler, 2010; Platt, 2012; Suarez-Orozco & Qin-Hillard, 2004), which can

increase intercultural competence (Rundstrom, 2005, Woolf, 2007). Global, or world,

citizens, are broadly defined as individuals traversing international borders who make

connections with those of differing backgrounds and worldviews (Adams & Carfagna,

2006) who then think of their relationships to self, others, and the world in a new way

(Karlberg, 2008). Study abroad and international education are one of many ways in

which diverse cultures of people are brought together globally, which facilitates added

complexity to the experience of one’s identity (Sheppard, 2004). As a result, individu-

als are now straddling multiple cultures, giving a sense of “living-in-between cultures”

(Bhatia & Ram, 2004, p. 237).

Several years ago, the Lincoln Commission declared the goal of sending one mil-

lion American students abroad by 2016 to 2017 (Commission on the Abraham Lincoln

Study Abroad Fellowship Program, 2005). In 2011, the number of students studying

abroad in the United States was approximately 270,604, tripling from two decades ago

(Institute of International Education, 2011) with a 150% increase in the past decade

(Gardner & Witherell, 2007). According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific

and Cultural Organization Institute for Statistics (UNESCO), 3.6 million students

were enrolled in various types of abroad programs in 2010 worldwide, reflecting a

78% increase in the last decade (UNESCO, 2012). Not all students interested in study

abroad have access to do so due to financial restriction, availability of relevant or

transferable courses abroad, time constraints for graduation, among other factors.

Nonetheless, the rate of students visiting countries outside of their homeland world-

wide continues to steadily increase. Thus, attention to the impact of sojourns abroad

on student identity should be considered.

Although study abroad is one of many aspects of global movement, it is a poten-

tially powerful one (Dolby, 2004). Research on study abroad depicts positive gains,

such as increased self-awareness, deeper interest in the well-being of others, an under-

standing of multinational issues (Kuh, 1995, as cited in Spiering & Erickson, 2006, p.

315), enlivened search for identity (Falk & Kanach, 2000), transformation in sense of

self, deeper experience of their own culture, enriched faith in their own capabilities,

and an increase in communication self-efficacy (Milstein, 2005). However, studies on

culture shock, re-entry shock, and cross-cultural adaptation report that some students

Downloaded from jee.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 8, 2016

Young et al. 177

experience psychological distress when studying abroad, which can last long after

their return (Ward & Kennedy, 1993). Those experiencing multiple re-entry, whether

in the form of transnational migration or multiple sojourns, report experiencing a com-

pounded sense of confusion with their place in the world. Personal identity, interper-

sonal relationships, and societal norms for these individuals are heavily affected

(Onwumechili, Nwosu, Jacksinn, & James-Hughes, 2003). Mental health profession-

als and educators, particularly in international education, can benefit from a deeper

understanding of the impact of study abroad on self-identity. To gain a better under-

standing of the impact on identity, the researchers examined how individuals negoti-

ated self-images amid novelty and global encounters with “the others” in their host

country.

Most models that explore the concept of identity were developed in a context that

predates modern globalization. Psychologists have yet to understand the consequences

that globalization will have on self-identity. Historically, self-identity has been an elu-

sive term in psychology. Identity is defined as one’s subjective view of one’s authentic,

or ideal, self (Rogers, 1980). The self has also been discussed as the conscious “I” that

produces multiple identities (May, 1953). Psychology literature is replete with defini-

tions of identity based on developmental theories. Identity has been defined as self-

image (Onorato & Turner, 2004) and self-concepts—a set of characteristics that remain

stable over time (Bailey, 2003). In Turner’s (1984) self-categorization theory (SCT), a

distinction is drawn between personal identity (unique character traits) and social

identity (shared traits with ingroup).

Identity is also viewed as a goal and state to be achieved. Erik Erikson addressed

identity achievement as one stage of psychosocial development occurring in adoles-

cence. Erikson thought that individuals completed tasks, or worked through certain

conflicts with one’s environment, to achieve a solid sense of self. Those who did not

successfully complete tasks were thought to move through life with a diffuse sense of

self (Erikson, 1968). Marcia (1966) expanded on Erikson’s work on identity achieve-

ment by focusing on ego identity development which was then adapted by Phinney

(1992) who evolved the ego identity model to create an ethnic identity model. Both

Phinney and Marcia’s models value the conflict that results when an individual auton-

omously explores their self and departs from the self as acquired through the lens of

their caretakers. This conflict, known as identity crises, leads to four outcomes:

Foreclosed, Diffuse, Moratorium, and Achieved, which delineate the level of autono-

mous exploration with which an individual engages before accepting their identity

(Marcia, 1966; Phinney & Ong, 2007). However, in our global village, the achieve-

ment of identity is ever elusive. Individuals and groups are no longer located in a sin-

gular homogeneous culture that contrasts itself from other cultures, but instead, they

are becoming increasingly integrated (Hermans & Dimaggio, 2007). As such, indi-

viduals now greet contrasting views, values, and belief systems more frequently,

increasing a sense of uncertainty (Hermans & Dimaggio, 2007). In addition, more

opportunities to negotiate identity and reflect on one’s place in the world are also pres-

ent (Karlberg, 2008). Identity is negotiable whenever one is faced with a new context,

making identity “multiple, contradictory, positional, contextual, partial, intersecting,

Downloaded from jee.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 8, 2016

178 Journal of Experiential Education 38(2)

continual [and] hybridized” (Jewett, 2010, p. 636). According to Dolby (2004), when

faced with adapting to a new context, individuals not only deepen their understanding

of the “other” but equally deepen their understanding of oneself. Living abroad allows

interviewees to experience themselves differently in new contexts.

Linguistic scholars have explained identity negotiation in terms of “positioning

theory,” that is, viewing identity as discourses taking place between individuals

(Blackledge & Pavlenko, 2001, p. 249). In each interaction, each person is taking a

position while simultaneously reacting to the other person’s position. Intercultural

communication is viewed as an interactional process where communicators compete

for social positions (Swann & Bosson, 2008). Existing literature on identity negotia-

tion proposes that acquisition of identity occurs through social interactions. Individuals

entering into new contexts, whether it is a new group or a new environment, grapple

with feelings of insecurity and vulnerability as they figure out how to be in the new

context (Swann, Milton, & Polzer, 2000; Ting-Toomey, 1999). According to intercul-

tural communications scholar, Ting-Toomey (1999), identity negotiation occurs when

one’s secure image of themselves is threatened when faced with difference or unfamil-

iar contexts. Identity negotiation is a transaction where individuals “attempt to evoke,

assert, define, modify, or challenge, and/or support their own and others’ desired self-

images” (Ting-Toomey 1999, p. 40). When negotiating identity, individuals will (a)

bring their self-image or perception of themselves, (b) acquire their identity via social

interactions, and (c) feel secure when engaging with supportive people in a familiar

environment (Ting-Toomey, 1999). When feeling threatened, insecure, or vulnerable

from engaging with dissimilar others, individuals decide to either assert or redefine

existing self-images (Swann et al., 2000; Ting-Toomey, 1999). Identity negotiation

can thus lead to shifts or changes in self-identity.

Without better understanding of the process of identity negotiation, educators,

mental health professionals, and global citizens risk being ill prepared for shifts in

self-identity that accompany study abroad, or other international journeys. This article

endeavors to study individuals’ sense of self-identity and process of identity negotia-

tion post study abroad. The research questions were as follows:

Research Question 1: How does study abroad change the interviewees’ experience

of himself or herself?

Research Question 2: How do the interviewees negotiate identity when entering

new contexts while studying abroad?

Method

At the beginning of the fall semester in 2008, invitations to participate in this study

were sent to returning study abroad students at a 4-year university and a 2-year com-

munity college in Southern California. Students recently returning from short-term

study abroad programs were invited to participate in the study. Countries visited were

China, Italy, Korea, Spain, Taiwan, and the United Kingdom. Durations of programs

ranged between 4 and 8 weeks.

Downloaded from jee.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 8, 2016

Young et al. 179

Five students elected to participate in the study. Two of the interviewees were men

and three were women. Ages ranged from 18 to 44 years. Interviewees identified as

Caucasian (3), Indian (1), and Asian (1). All interviewees identified as undergraduate

students. Three students studied in the United Kingdom and indicated previous inter-

national travel experience limited to family vacations ranging from 1 to 3 weeks. Two

students indicated no previous international travel experience. None of the interview-

ees have lived abroad prior to their study abroad experience. Interviews averaged 1 hr

in duration. All interviews were conducted within 1 month of interviewees’ return to

the United States. All interviews were video and audio recorded and transcribed with

interviewees’ informed consent.

Saturation was reached by the fifth interview; therefore, no further interviews were

conducted. The interview questions include but are not limited to (a) What stood out

to you the most in your entire study abroad experience? (b) What makes that experi-

ence/event significant? (c) How did that experience/event change your experience of

yourself?

A content analysis was performed on interview data. Peer debriefing was used to

establish the credibility of qualitative data (Creswell, 2013). Two types of peer debrief-

ing were used (Leech & Onwuegbuzie, 2008). The first type of debrief focused on creat-

ing intercoder reliability. The first and second authors, along with a third colleague who

was uninvolved with the study but familiar with qualitative methods, independently

reviewed and coded the qualitative data. The three scholars reviewed the interview tran-

scripts for emerging themes. Points of differences in the coding and interpretations were

discussed and a consensus was reached before continuation of coding.

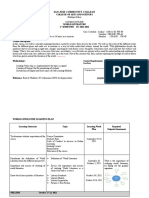

Emerging themes were drawn from the qualitative data and were named using the

language of the interviewees (indigenous typologies). Authors also reviewed identity

negotiation literature to help structure and code emerging themes. Turner’s (1984)

SCT theory of identity was used to structure identity negotiation outcomes. Subthemes

were named: Supporting Identity, Adapting Identity, and Modifying Identity.

The second type of debrief focused on establishing credibility by consulting with a

knowledgeable peer. Thus, the third author was contacted to review the whole study

and provide feedback to help resolve methodological issues and explore aspects of the

study that may have remained unnoticed (Leech & Onwuegbuzie, 2008).

Results

The main category was titled Identity Negotiation during Study Abroad. Under this

category, two themes emerged: Reactions to Context and Negotiation Outcomes. Each

theme has several subthemes. Pseudonyms have been used to protect the anonymity of

the interviewees.

Reaction to Context

Interviewees shared their reactions to cultural differences within their new contexts by

recounting conversations, events, and observations of their host culture. Interviewees

Downloaded from jee.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 8, 2016

180 Journal of Experiential Education 38(2)

spoke of experiencing positive feelings and described that their host culture was “cool”

and “friendly.” All interviewees agreed that their experience studying abroad brought

about lasting personal and academic benefits. The most significant encounters in their

new contexts were associated with difficult emotions which were accompanied by

cognitions, or thoughts, that led to their behaviors.

Emotions. All interviewees indicated interactions with locals in their host country

wherein strong emotional reactions were experienced. Encounters where interviewees

experienced feelings of anger, annoyance, and vulnerability were significant as they

took the most time to recount during the interviews.

Anger. “I was so pissed!”. During the first 2 weeks of being abroad in the United

Kingdom, Ana witnessed a British female adolescent attack a female peer in Ana’s

group by pulling the woman’s hair while a British male yelled to the group, “Yeah

that’s right, this is our country!” Ana’s voice was raised during the interview as she

stated “I was so pissed, I was livid . . . if she got this American by [my] hair, she would

not be standing right now!” Ana stated that she “closed off” to socializing with the

British after the incident. She said, “If [the British] don’t accept me, I’m not going to

accept [the British].” Ana’s mood was affected as she ruminated about the incident

stating that she would have acted more aggressively had the incident taken place in

the United States. Ana withdrew from her peers and stated she felt “resentful” toward

locals. Ana’s feelings and behaviors were tainted by the incident and she developed a

negative attitude toward the British that blanketed her overall study abroad experience.

Annoyance. “After 15 min of being so annoyed . . .”. While on the subway with

friends in the United Kingdom, Jin spoke of feeling “annoyed” when “harassed” by an

older British male. Jin reported that the man was “obnoxious” and repeatedly asked Jin

and his friends if they knew of Dirty Harry. When Jin responded that they did not know

Dirty Harry, the man cried out “freakin’ Yanks!” Jin felt “shocked” and “confused”

about why the local was interrogating Jin and his friends about Dirty Harry.

We were like, “whoa buddy calm down. Who’s Dirty Harry? Why can’t you just tell us

who he is?” . . . And finally, after like, 15 minutes of being so annoyed, he’s finally like

“yeah, Dirty Harry is . . . Clint Eastwood.”

Vulnerability. “I felt stupid.” All interviewees shared experiences where they felt

vulnerable while living abroad. For example, all interviewees who studied in the

United Kingdom indicated feeling “stupid,” “awkward,” or “ignorant.”

Jin: I feel kind of ignorant in a way . . . [The British] are way more aware of the

world and not as ignorant, I would say, as us [Americans]. Yeah, they know

what’s going on and actually care about what’s going on . . ..

Terrance: When I was [in the United Kingdom], I felt stupid, ignorant, . . . less

worldly . . .

Downloaded from jee.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 8, 2016

Young et al. 181

Ana: . . . It’s their demeanor, [the British] had a harsher mentality as far as intelligence

. . . most of the Brits don’t yell and scream. They just hit you with the intellect . . .

Cindy: In a lot of places you’re the only Asian . . . you feel kind of awkward . . .

Cognitions and behaviors. All interviewees’ shared their thoughts and behaviors result-

ing from interactions with locals in their host country. All interviewees engaged in

self-reflection to deepen their understanding of exchanges with locals. It appeared that

their cognitions often informed behaviors. The behaviors that emerged from the data

were coded as follows: Observe, Rationalize, and Avoid.

Observe. “Professors are buying students beers . . . and just chill.” Interviewees

who observed simply noticed interactions or events in their new context and made

judgments based on their own values and belief systems. Cindy reported observing

more frequent public displays of affection and support of LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisex-

ual, transgender, queer) relationships while in the United Kingdom. Cindy also shared

feeling “awkward” that professors socialize with students at the pub. “I mean, profes-

sors are buying students beers . . ..” These observations led to self-reflection of her

values and biases and desired self-image. Cindy stated, “[The British] were just more

open to these kinds of things . . . I’m not used to seeing that . . . maybe I just need to

get out of the [United States] more.”

Rationalize. “Maybe he just had a bad day.” Interviewees rationalized encounters

with locals from host country that were unpleasant. For example, during a weekend

trip to Paris, France, Terrance described an exchange with a Parisian taxi driver who

yelled at him “no Americans!” and drove off when Terrance attempted to use his ser-

vice. Terrance was “taken back by it” and rationalized the driver’s behavior. Terrance

stated “it was at two in the morning. I’m sure he’s had plenty of Americans who got

drunk and threw up on his seats but I was just like wow . . ..”

Rationalizing was also used when Ana began to socialize with her peers again after

a period of isolation post altercation with the British adolescents. Ana stated that she

“debriefed” with her peers, helping Ana build a new perspective of the incident and

enabled her to eventually “let go.”

I had to talk it out a lot . . . cussing, saying the same thing over and over for days . . . and

then at some point in my mind um I actually say . . . that one person does not dictate what

everybody feels, and everybody is different . . .. Then it just dissipated, I let it go.

Annoyed with the man on the train inquiring about Dirty Harry, Jin made sense of

the interaction by rationalizing the man’s behavior as a representation and a reminder

of normal human flaws.

He stated,

Well it just made me realize that people are mean everywhere . . . we met a lot of nice

people . . . but not everyone is amazing . . . not everyone is nice and friendly all the time.

Downloaded from jee.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 8, 2016

182 Journal of Experiential Education 38(2)

Interviewees visiting the United Kingdom used rationalizing when they spoke of

feeling “stupid” and “ignorant” for their apparent lack of “world knowledge” when

comparing themselves with the British. Jin rationalized that U.K.’s efficient public

transportation system allowed people time on their commute to follow up on news

whereas in California, people were always driving and had less time to keep up with

current events. Terrance stated that the English news media broadcasted global current

events, in contrast with American news media which focused mostly on domestic

events. Jin, Ana, and Terrance all indicated reassessing their values and decided to put

more effort to learn more about the world by following global news or studying world

history.

Avoidance. “I had to walk away.” In his exchange with the man asking about Dirty

Harry, Jin felt annoyed and avoided further engagement with the man by leaving the

train. “I was just so annoyed I had to walk away.” Cindy avoided feeling “awkward”

socializing with professors by avoiding invitations to the pub. “I tended to avoid those

environments if I could.”

Negotiation Outcomes

Supporting identity

“I’m just more closed off.” Interviewees appeared to support their identity by

upholding their original self-image when it related to social identity (shared traits with

ingroup). Despite experiencing cultural differences positively, interviewees supported

their original self-images when concerned about others’ perceptions. For instance,

Cindy described the British as “very hospitable” and “more open compared to Ameri-

cans.” She appreciated that professors and students had a “casual” and more “personal

relationship” in the United Kingdom and stated it was “pretty cool,” but still upheld

her original self-image as “conservative” and someone who “respects authority.” She

explained,

I actually don’t feel too comfortable addressing people of authority or people older than

me by their first names because I feel like I’m being disrespectful. I’d say this is probably

due to a strong influence from my parents and the [Asian] tradition of respect and social

etiquette . . . I’m just more closed off I guess.

“Part of my confidence comes from how I look.” Terrance admired women in the

United Kingdom stating that they were more “comfortable with their body shape”

and possessed healthier body image than women in California. He stated that British

women “didn’t try to hide their weight at all” and did not “tie their confidence with

how they looked.” Despite his admiration, Terrance upheld his original self-image as

someone who could not accept himself if he had a larger body shape. He stated,

Part of my confidence comes from how I look and I don’t think I can accept their carefree

thought of like, you know, I look how I look, you know . . .

Downloaded from jee.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 8, 2016

Young et al. 183

Interviewees supported existing self-images if modifying meant risking acceptance

in social groups. More specifically, Cindy’s adherence to maintaining interpersonal

boundaries with members of authority and Terrance’s unwavering value of his outer

appearance suggest that these messages were learned to be appropriate for social

acceptance and changing these values may risk rejection from social groups. Thus,

interviewees continued to support their existing self-images despite expressed admira-

tion or positive sentiments toward the difference.

Adapting Identity

“We felt like locals by the time we left.” Two interviewees temporarily modified self-

images and behaviors while abroad to adapt to the new context and reverted to their

original self-images on returning home to the United States. For example, Lisa shared

that she experienced herself as “open” and “affectionate” while in Spain, which con-

trasted from her pre-abroad self-image as “open but more reserved.” Lisa described

Spaniards as affectionate stating that they “kiss, kiss and hug” when greeting each

other. She experimented with her self-image by being more affectionate with others;

however, after returning to the United States, Lisa felt that she was not “bold” enough

to continue being affectionate. Lisa was conscious that her family and friends in the

United States may feel “awkward.”

Modifying identity. All interviewees reported some change in self-image before and after

studying abroad. All interviewees modified identity when it was related to personal

identity (unique character traits) rather than social identity (shared traits with ingroup).

“I want to know more.” All interviewees studying in the United Kingdom felt that

the British were much more aware of global issues and described them as “witty” and

“smarter” than Americans.

Jin: I constantly thought about it . . . when I go back [to the United States], I’m

going to start listening to the news more and going to start reading more and I’m

going to start relaxing more instead of sitting around the house and watching TV

. . . I feel like learning more, I want to learn more, I want to know more . . .

what’s going on in the world . . . be more informed.

Terrance: I felt ignorant . . . I want to pick up the paper or read a book while I’m on

BART . . . not listen to some stupid radio show . . . [I felt] less worldly . . . I want

to [learn] another language.

Ana: . . . it got me a heck of a lot more interested in history again . . . I always knew

history is important. I’ve just moved it way up on my ranking because of this

experience.

Cindy: [Study abroad] helped me be more open minded . . . you think you know

everything until you go out there.

“I have something to work with still so I should work with it.” Ana described her

self-image as a “tomboy,” stating that she often dressed in “baseball caps” and

Downloaded from jee.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 8, 2016

184 Journal of Experiential Education 38(2)

unfeminine clothing. However, while visiting Italy, Ana found herself desiring to mod-

ify her self-image when observing Italian women “taking more care of themselves.”

She felt inspired to modify her existing self-image from a “tomboy to [sic] a woman

who puts more effort into her appearance.” When she returned to the United States,

Ana adjusted her wardrobe so that it was “cute and flattering.” She stated, “I have

something to work with still so I should work with it.”

“I feel like a tiny, tiny part of me is Spanish.” Lisa described herself being immersed

in Spanish culture “living with a Spanish family, attending a Spanish school, going to

Spanish parties . . . all of this made me realize that we are all the same.” Lisa grew in

her desire to learn about culture and people and decided to change her major from Art

History to Anthropology or Cultural studies. Lisa also indicated that she would like to

travel to South America and continue improving her Spanish language skills. The shift

in her self-image was demonstrated when she stated, “I feel like I have a connection

with the culture . . . I feel like a tiny, tiny part of me is Spanish.”

Discussion

Some key findings of this study regarding identity negotiation were demonstrated by

interviewees’ shared experiences of emotional discomfort and cognitive processes

when interacting with locals abroad. The data showed that interviewees experienced

anger, annoyance, and/or vulnerability and processed emotions by rationalizing,

observing, or avoiding. All interviewees used observing and rationalizing to under-

stand their experiences in host cultures. Interviewees felt a level of vulnerability when

confronting differences regardless of whether they decided to support or modify self-

images. Those who chose to support existing self-images used rationalizing, observ-

ing, and avoiding. Temporary modifications to self-image were made by using

rationalizing and observing. No difficult emotions were reported when making tempo-

rary modifications. Those who chose to modify self-images primarily used rational-

izing and observing and reported experiencing anger, annoyance, and vulnerability.

Interviewees who described experiencing a sense of vulnerability after an encounter

with the host culture highlighted the differences between them and “other.” All inter-

viewees modified at least one aspect of their self-image while abroad.

The results of the study are aligned with theories of Identity Negotiation. More

specifically, Ting-Toomey (1999) suggested that dealing with feelings of emotional

vulnerability or experiencing emotional discomfort when facing dissimilar others is

what facilitates growth as people “listen with greater thoughtfulness and see things

through fresh lenses” (p. 8). In this study, interviewees’ reported feeling “ignorant,”

“stupid,” and “less worldly” and indicated feeling vulnerable and/or uncomfortable.

Struggling with discomfort propagated the interviewees’ decision to support or modify

self-images, or identity. This finding supports Ting-Toomey’s suggestions that the

struggle between identity security (feeling supported and respected) and identity vul-

nerability (feeling threatened) in new contexts allows individuals to embrace new

frameworks of self-identity (Ting-Toomey, 1999).

Downloaded from jee.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 8, 2016

Young et al. 185

A unique finding in the data was that identity modifications to self-images were

made only if they did not threaten interviewees’ social identity. For example, Terrance

did not change his value of physical appearance despite stating that he admired British

women for being comfortable with their body types. Having a different body type

could be viewed as a threat to social acceptance and self-confidence. Similarly, Cindy

felt that her Asian identity made her more conservative and thus she did not challenge

herself to socialize casually with her professors in the United Kingdom despite appre-

ciating the lack of formality between professors and students. Modifications were

made when it involved personal identity only. Social identity theorists would explain

this by emphasizing the importance of group identification (Swann, Gomez, Seyle,

Morales, & Huici, 2009) and fears of being ostracized by one’s ingroup(s). For

instance, identity theorists postulate that individuals tend to discard parts of them-

selves deemed unacceptable by parents and/or dominant society (Erikson, 1968;

Marcia, 1966; Myers et al., 1991). As such, differing from the dominant group can be

perceived as threatening. The fear of not belonging or separating from social group

can deter individuals from adjusting values and experimenting with self-identity. This

can explain why interviewees did not modify self-images when social identity was

threatened.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Interviews were limited to the experiences of those who studied abroad in Spain and

the United Kingdom. Another limitation is that four of five interviewees studied

abroad in the United Kingdom and one studied abroad in Spain. Future qualitative

studies should carefully consider their recruitment. Recruiting interviewees living

abroad in the same country is suggested to increase homogeneity. However, recruiting

a sample from diverse countries can also serve to increase validity of emerging themes.

Future research in this area can also include interviewees who study abroad in a vari-

ety of countries and from different continents. Finally, the length of time spent abroad

was relatively short. The average time spent studying abroad was 5 weeks. It is pre-

sumed that spending a full semester or a full year abroad could alter interviewees’

experiences. Recruiting interviewees who have studied abroad in full semester or full

year programs may provide richer data to understand any modifications in self-image

while abroad. Long-term follow-up interviews (i.e., 1 year post re-entry into the home

country) is suggested to note any changes on reintegration into their home culture.

Conclusion

This study concurs with suggestions that a new way of conceptualizing identity and

identity development is indicated (Dolby, 2004; Heppner, 2006). Global citizenry is on

the rise, and individuals find themselves simultaneously immersed in multiple cultures

and juggling a self-identity that is in flux. The authors suggest that identity for global

citizens is in a constant state of flux. Rather than being stable, identity is a continual

process of integrating new experiences and molding values, roles, and self-images

Downloaded from jee.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 8, 2016

186 Journal of Experiential Education 38(2)

based on context. Further research in this area is recommended to understand the

implications of working with exchange students who embody an identity in flux.

Clinicians and educators are cautioned to avoid simplifying exchange students with

identities in flux as being identity diffused or in identity crisis. Pathological general-

izations can be harmful and counterproductive. Instead, clinicians and educators are

encouraged to adopt a disposition of curiosity and view each individual as a unique

blend of his or her diverse contexts and global encounters.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship,

and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of

this article.

References

Adams, J. M., & Carfagna, A. (2006). Coming of age in a globalized world: The next genera-

tion. Bloomfield, CT: Kumarian Press.

Bailey, J. A. (2003). Self-image, self-concept, and self-identity revisited. Journal of National

Medical Association, 95, 383-386.

Bhatia, S., & Ram, A. (2004). Culture, hybridity, and the dialogical self: Cases from the south

Asian diaspora. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 11, 224-240.

Blackledge, A., & Pavlenko, A. (2001). Negotiation of identities in multilingual contexts.

International Journal of Bilingualism, 5, 243-257.

Chen, G. M., & Starosta, W. J. (2000, November 8–12). The development and validation of

the intercultural sensitivity scale. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the National

Communication Association, Seattle, WA.

Commission on the Abraham Lincoln Study Abroad Fellowship Program. (2005). Global compe-

tence and national needs: One million Americans studying abroad. Washington, DC: Author.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five

approaches (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Dolby, N. (2004). Encountering an American self: Study abroad and national identity.

Comparative Education Review, 48, 150-173.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

Falk, R., & Kanach, N. A. (2000). Globalization and study abroad: An illusion of paradox.

Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad, 6, 155-168.

Gardner, D., & Witherell, S. (2007). American students studying abroad up to record levels:

8.5%. Retrieved from http://opendoors.iienetwork.org/?p=113744

Heppner, P. (2006). The benefits and challenges of becoming cross-culturally competent coun-

seling psychologists: Presidential address. The Counseling Psychologist, 34, 147-172.

Hermans, H. J., & Dimaggio, G. (2007). Self, identity, and globalization in times of uncertainty:

A dialogical analysis. Review of General Psychology, 11, 31-61.

Institute of International Education. (2011). Open Doors 2011 Fast Facts [Data file]. Retrieved

from http://www.iie.org/en/Research-and-Publications/Research-Projects/~/media/Files/

Corporate/Open-Doors/Fast-Facts/Fast%20Facts%202011.ashx

Downloaded from jee.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 8, 2016

Young et al. 187

Jewett, S. (2010). “We’re sort of imposters”: Negotiating identity at home and abroad.

Curriculum Inquiry, 40, 636-656.

Karlberg, M. (2008). Discourse, identity, and global citizenship. Peace Review: A Journal of

Social Justice, 20, 310-320.

King, P. M., & Magolda, M. B. (2005). A developmental model of intercultural maturity.

Project Muse, 46, 571-592.

Leech, N. L., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2008). Debriefing. In L. M. Given (Ed.), The SAGE ency-

clopedia of qualitative research (pp. 199-201). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Marcia, J. E. (1966). Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology, 3, 551-558.

May, R. (1953). Man’s search for himself. London, England: W.W. Norton.

Miller, J. K., Todahl, J., Platt, J. J., Lambert-Shute, J., & Eppler, C. (2010). Internships for

future faculty: Meeting the career goals of the next generation of educators in marriage and

family therapy. Journal of Marital & Family Therapy, 36, 71-79.

Milstein, T. (2005). Transformation abroad: Sojourning and the perceived enhancement of self-

efficacy. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29, 217-238.

Myers, L. J., Speight, S. L., Highlen, P. S., Cox, C. I., Reynolds, A. L., Adams, E. M., & Hanley,

C. P. (1991). Identity development and worldview: Toward an optimal conceptualization.

Journal of Counseling & Development, 70, 54-63.

Onorato, R. S., & Turner, J. C. (2004). Fluidity in the self concept: The shift from personal to

social identity. European Journal of Social Psychology, 34, 257-278.

Onwumechili, C., Nwosu, P. O., Jacksinn, R. L., & James-Hughes, J. (2003). In the deep valley

with mountains to climb: Exploring identity and multiple reacculturation. International

Journal of Intercultural Relations, 27, 41-62.

Phinney, J. S. (1992). The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse

groups. Journal of Adolescent Research, 7, 156-176.

Phinney, J. S., & Ong, A. (2007). Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current

status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54, 271-281.

Platt, J. J. (2012). A Mexico City based immersion education program: Training mental health

workers for practice with Latino communities. Journal of Marital & Family Therapy, 38,

352-364.

Rogers, C. (1980). A way of being. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin.

Rundstrom, W. T. (2005). Exploring the impact of study abroad on students’ intercultural

communication skills: Adaptability and sensitivity. Journal of Studies in International

Education, 9, 356-371.

Sheppard, K. (2004). Global citizenship: The human face of international education.

International Education, 34, 34-40.

Spiering, K., & Erickson, S. (2006). Study abroad as innovation: Applying the diffusion model

to international education. International Education Journal, 7, 314-322.

Suarez-Orozco, C., & Qin-Hilliard, D. B. (Eds.). (2004). Globalization culture and education in

the new millennium. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Sue, D. W., Arredondo, P., & McDavis, R. J. (1992). Multicultural counseling competen-

cies and standards: A call to the profession. Journal of Counseling & Development, 70,

477-486.

Swann, W. B., Jr., & Bosson, J. (2008). Identity negotiation: A theory of self and social inter-

action. In O. John, R. Robins, & L. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality psychology:

Theory and research (pp. 448-471). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Downloaded from jee.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 8, 2016

188 Journal of Experiential Education 38(2)

Swann, W. B., Jr., Gomez, A., Seyle, D. C., Morales, J. F., & Huici, C. (2009). Identity fusion:

The interplay of personal and social identities in extreme group behavior. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 995-1011.

Swann, W. B., Jr., Milton, L. P., & Polzer, J. T. (2000). Should we create a niche or fall in

line? Identity negotiation and small group effectiveness. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 79, 238-250.

Ting-Toomey, S. (1999). Communicating across cultures. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Turner, J. C. (1984). Social identification and psychological group formation. In H. Tajfel

(Ed.), The social dimension: European developments in social psychology (pp. 518-536).

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Institute for Statistics. (2012).

Global flow of tertiary level students [Data file]. Retrieved from http://www.uis.unesco.

org/education/Pages/international-student-flow-viz.aspx

Ward, C., & Kennedy, A. (1993). Psychological and socio-cultural adjustment during cross-cul-

tural transitions: A comparison of secondary students overseas and at home. International

Journal of Psychology, 28, 129-147.

Woolf, M. (2007). Impossible things before breakfast: Myths in education abroad. Journal of

International Education, 11, 496-509.

Author Biographies

Jennifer T. Young, PsyD, is a psychologist at Counseling and Psychological Services at

California State University, Long Beach.

Rajeswari Natrajan-Tyagi, PhD, is the program director and associate professor in the Couples

and Family Therapy Program for the California School of Professional Psychology, Alliant

International University, Irvine.

Jason J. Platt, PhD, is the program director of the International Counseling Psychology

Program and the California School of Professional Psychology Spanish Language, Class, and

Culture Immersion Program for the California School of Professional Psychology, Alliant

International University, Mexico City.

Downloaded from jee.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 8, 2016

You might also like

- Cultural Exposure Emotional IntelligenceDocument18 pagesCultural Exposure Emotional IntelligenceBat Knight ThapayomNo ratings yet

- The 4 Parenting StylesDocument4 pagesThe 4 Parenting StylesJeff Moon100% (3)

- Niche Travel High CPCDocument399 pagesNiche Travel High CPCSuparman JaiprajnaNo ratings yet

- Community Organizing Participatory Research (COPAR)Document4 pagesCommunity Organizing Participatory Research (COPAR)mArLoN91% (11)

- Students at Risk of Dropping Out of School Childrens VoicesDocument24 pagesStudents at Risk of Dropping Out of School Childrens VoicesJade RomorosaNo ratings yet

- Multivariate Data AnalysisDocument17 pagesMultivariate Data Analysisduniasudahgila50% (2)

- The Impact of Social Media On The Self-Esteem of Youth 10 - 17 Year PDFDocument49 pagesThe Impact of Social Media On The Self-Esteem of Youth 10 - 17 Year PDFCarryl Rose Benitez100% (1)

- Characteristics of Informational TextDocument2 pagesCharacteristics of Informational TextEdwin Trinidad100% (1)

- Assessing Student Learning Outcomes Exercises A. List Down Three (3) Supporting Student Activities To Attain of The Identified Student LearningDocument19 pagesAssessing Student Learning Outcomes Exercises A. List Down Three (3) Supporting Student Activities To Attain of The Identified Student LearningLexie Renee Uvero89% (9)

- Bicultural Existence in a Globalized Era (6)Document23 pagesBicultural Existence in a Globalized Era (6)Angelo Villarin PomboNo ratings yet

- DocsDocument18 pagesDocsSachi UncianoNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Research Publications Volume-62, Issue-1, October 2020Document20 pagesInternational Journal of Research Publications Volume-62, Issue-1, October 2020bye, pau.No ratings yet

- Cultural exposure impacts cultural intelligenceDocument19 pagesCultural exposure impacts cultural intelligenceagustin floresNo ratings yet

- Review JurnalDocument3 pagesReview JurnalnabilahNo ratings yet

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTDocument44 pagesACKNOWLEDGEMENTAngelyn De ArceNo ratings yet

- Study Abroad Impacts On Ethnocentrism and Intercultural Communication CompetenceDocument21 pagesStudy Abroad Impacts On Ethnocentrism and Intercultural Communication Competenceapi-579794839No ratings yet

- VoluntourismDocument15 pagesVoluntourismapi-611564020No ratings yet

- 1385-Article Text-4897-1-10-20230816Document13 pages1385-Article Text-4897-1-10-20230816winniewine24No ratings yet

- Intercultural Reflection Paper #4Document5 pagesIntercultural Reflection Paper #4Jedidiah Jireh AncianoNo ratings yet

- Study Abroad Impacts On Ethnocentrism and Intercultural Communication CompetenceDocument42 pagesStudy Abroad Impacts On Ethnocentrism and Intercultural Communication Competenceapi-548814034No ratings yet

- 3 BykerDocument22 pages3 BykerGONZALEZ OCAMPO DIANA KATHERINENo ratings yet

- 5 Examining Cultural Intelligence and Cross-Cultural Negotiation EffectivenessDocument36 pages5 Examining Cultural Intelligence and Cross-Cultural Negotiation Effectivenessjayalab97No ratings yet

- Transformative Intercultural Learning A Short Term International Study TourDocument15 pagesTransformative Intercultural Learning A Short Term International Study TourAndrew Sauer PA-C DMScNo ratings yet

- Internationalization Remodeled - Definition - Approaches - and RationalesDocument28 pagesInternationalization Remodeled - Definition - Approaches - and RationalesCelene Fidelis Frias FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Graduate School Batangas City P. Prieto St. Batangas City, Batangas 4200Document8 pagesGraduate School Batangas City P. Prieto St. Batangas City, Batangas 4200CarlaNo ratings yet

- Rogoff Et Al 2017Document13 pagesRogoff Et Al 2017Andre do AmaralNo ratings yet

- 1Document7 pages1jejejeNo ratings yet

- Viewpoint DeardorffDocument4 pagesViewpoint DeardorffEma AlinaNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id3781250Document14 pagesSSRN Id3781250Ryniel RullanNo ratings yet

- Communication and Identity Management in A Globallyconnected Classroom An Online International andDocument19 pagesCommunication and Identity Management in A Globallyconnected Classroom An Online International andIma MustaqimahNo ratings yet

- The Youth's Diversity in Identity An Era of FlourishingDocument8 pagesThe Youth's Diversity in Identity An Era of FlourishingJhanelle Mariel R. GuavesNo ratings yet

- Intercultural Communication and Friendship Development On Social MediaDocument12 pagesIntercultural Communication and Friendship Development On Social MediaMumbe KaslimNo ratings yet

- Reading Course 11 - UdeA - Class 3Document2 pagesReading Course 11 - UdeA - Class 3ÉVER ANDRÉS Guerra GuerraNo ratings yet

- Definition of Intercultural Competence According To Undergraduate Students at An International University in GermanyDocument22 pagesDefinition of Intercultural Competence According To Undergraduate Students at An International University in GermanyGabby LupuNo ratings yet

- Self Identity PDFDocument15 pagesSelf Identity PDFtwitter joshNo ratings yet

- Towards The Global Living - MunifDocument18 pagesTowards The Global Living - MunifMunif TokNo ratings yet

- Culture Shock or Challenge - The Role of Personality As A Determinant of Intercultural CompetenceDocument13 pagesCulture Shock or Challenge - The Role of Personality As A Determinant of Intercultural CompetenceAnaPaulaVC26No ratings yet

- Arrojo CasestudyfinalDocument19 pagesArrojo Casestudyfinalapi-447698563No ratings yet

- Lived-In Experiences of International Students in Indian University: Enculturation, Emigration & ResilienceDocument6 pagesLived-In Experiences of International Students in Indian University: Enculturation, Emigration & ResilienceInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Student Self Formation in International EducationDocument17 pagesStudent Self Formation in International EducationmavoudoudamsouNo ratings yet

- AsiaTEFL V20 N2 Summer 2023 Demystifying The Narrative of A Former International Student in TESOL Reflecting On A Post Interview StudyDocument9 pagesAsiaTEFL V20 N2 Summer 2023 Demystifying The Narrative of A Former International Student in TESOL Reflecting On A Post Interview StudywmyartawanNo ratings yet

- Sample Study For Research IPDF PDFDocument51 pagesSample Study For Research IPDF PDFQueenny Simporios LlorenteNo ratings yet

- Tanauan City College: Learning Module FormatDocument3 pagesTanauan City College: Learning Module FormatJessa Melle RanaNo ratings yet

- UnderstandingsDocument7 pagesUnderstandingscoribrooks4No ratings yet

- Improving Intercultural Adaptableness of Culturally Diverse Students in An International University Environment'Document14 pagesImproving Intercultural Adaptableness of Culturally Diverse Students in An International University Environment'Gurung AnshuNo ratings yet

- Commuter Students Literature ReviewDocument13 pagesCommuter Students Literature Reviewapi-414897560100% (1)

- Lo NarrativeDocument24 pagesLo Narrativeapi-662891801No ratings yet

- Apa Writing Format Template 59Document5 pagesApa Writing Format Template 59api-665005803No ratings yet

- Culture and Creativity - Examining Variations in Divergent Thinking Within Norwegian and Canadian CommunitiesDocument13 pagesCulture and Creativity - Examining Variations in Divergent Thinking Within Norwegian and Canadian CommunitiesFox SanNo ratings yet

- Creativity and Intercultural Experiences: The Impact of University International ExchangesDocument25 pagesCreativity and Intercultural Experiences: The Impact of University International Exchangeshoomesh waranNo ratings yet

- PrelimDocument9 pagesPrelimbrice burgosNo ratings yet

- Benefits of Peer Editing Workshops To Promote Youth Engagement With Traditional CultureDocument9 pagesBenefits of Peer Editing Workshops To Promote Youth Engagement With Traditional CultureInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Action Research in Social NetworkingDocument15 pagesAction Research in Social Networkingnikko norman100% (1)

- Place Attachment and Place Identity Undergraduate Students'Document8 pagesPlace Attachment and Place Identity Undergraduate Students'davve98hNo ratings yet

- 2017-7!4!11 Ivy League ExperienceDocument15 pages2017-7!4!11 Ivy League ExperienceSTAR ScholarsNo ratings yet

- Social Networkingand Academic Performanceamong Filipino StudentsDocument13 pagesSocial Networkingand Academic Performanceamong Filipino StudentsJoshua Guerrero CaloyongNo ratings yet

- The Institutional Identity Formation ProDocument7 pagesThe Institutional Identity Formation ProScarlet LabinghisaNo ratings yet

- Learning and Individual Di FferencesDocument10 pagesLearning and Individual Di FferencesSouhir KriaaNo ratings yet

- All before Them: Student Opportunities and Nationally Competitive FellowshipsFrom EverandAll before Them: Student Opportunities and Nationally Competitive FellowshipsNo ratings yet

- Students' Identities Shape Learning in Multicultural ClassroomsDocument18 pagesStudents' Identities Shape Learning in Multicultural ClassroomsBERNARD RICHARD NAINGGOLANNo ratings yet

- DAVIS and DOLAN 2016 Contagious Learning. Drama, Exp. and PerezhivanieDocument19 pagesDAVIS and DOLAN 2016 Contagious Learning. Drama, Exp. and PerezhivanieMarisol de DiegoNo ratings yet

- Cross-Cultural TransitionsDocument23 pagesCross-Cultural TransitionsHoài ThươnggNo ratings yet

- Capstone Speech Final 2Document6 pagesCapstone Speech Final 2api-256511577No ratings yet

- Mckenzie, J. (2016)Document38 pagesMckenzie, J. (2016)LeGrand BeltranNo ratings yet

- Green 2018 Engaging Students in International Education Rethinking Student Engagement in a Globalized WorldDocument7 pagesGreen 2018 Engaging Students in International Education Rethinking Student Engagement in a Globalized WorldAbhi_kumarNo ratings yet

- Tesis Part IIDocument17 pagesTesis Part IIHerQ C.No ratings yet

- Cube Roots of Unity (Definition, Properties and Examples)Document1 pageCube Roots of Unity (Definition, Properties and Examples)Nipun RajvanshiNo ratings yet

- San Antonio Elementary School 3-Day Encampment ScheduleDocument2 pagesSan Antonio Elementary School 3-Day Encampment ScheduleJONALYN EVANGELISTA100% (1)

- Chem237LabManual Fall2012 RDocument94 pagesChem237LabManual Fall2012 RKyle Tosh0% (1)

- Productivity Software ApplicationsDocument2 pagesProductivity Software ApplicationsAngel MoralesNo ratings yet

- 3rd Monthly ExamDocument4 pages3rd Monthly ExamRoselyn PinionNo ratings yet

- San Jose Community College: College of Arts and SciencesDocument5 pagesSan Jose Community College: College of Arts and SciencesSH ENNo ratings yet

- Importance of Active ListeningDocument13 pagesImportance of Active ListeningJane Limsan PaglinawanNo ratings yet

- PMP Training 7 2010Document5 pagesPMP Training 7 2010srsakerNo ratings yet

- Scoliosis Guide: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis & TreatmentDocument5 pagesScoliosis Guide: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis & TreatmentDimple Castañeto CalloNo ratings yet

- Shabnam Mehrtash, Settar Koçak, Irmak Hürmeriç Altunsöz: Hurmeric@metu - Edu.trDocument11 pagesShabnam Mehrtash, Settar Koçak, Irmak Hürmeriç Altunsöz: Hurmeric@metu - Edu.trsujiNo ratings yet

- Participation Rubric 2Document1 pageParticipation Rubric 2api-422590917No ratings yet

- Archive of SID: The Most Well-Known Health Literacy Questionnaires: A Narrative ReviewDocument10 pagesArchive of SID: The Most Well-Known Health Literacy Questionnaires: A Narrative ReviewShaina Fe RabaneraNo ratings yet

- Memoir Reflection PaperDocument4 pagesMemoir Reflection Paperapi-301417439No ratings yet

- Hildegard Peplau TheoryDocument28 pagesHildegard Peplau TheoryAlthea Grace AbellaNo ratings yet

- Abm-Amethyst Chapter 2Document12 pagesAbm-Amethyst Chapter 2ALLIYAH GRACE ADRIANONo ratings yet

- University - HPS431 Psychological Assessment - Week 4 Learning Objective NotesDocument5 pagesUniversity - HPS431 Psychological Assessment - Week 4 Learning Objective Notesbriella120899No ratings yet

- Smart Lesson Plan WwiiDocument3 pagesSmart Lesson Plan Wwiiapi-302625543No ratings yet

- 15 05 2023 Notification Ldce SdetDocument3 pages15 05 2023 Notification Ldce SdetPurushottam JTO DATA1100% (1)

- Straight To The Point Evaluation of IEC Materials PDFDocument2 pagesStraight To The Point Evaluation of IEC Materials PDFHasan NadafNo ratings yet

- MAPEHDocument2 pagesMAPEHLeonardo Bruno JrNo ratings yet

- Letterhead Doc in Bright Blue Bright Purple Classic Professional StyleDocument2 pagesLetterhead Doc in Bright Blue Bright Purple Classic Professional StyleKriszzia Janilla ArriesgadoNo ratings yet

- Trigonometric Ratios: Find The Value of Each Trigonometric RatioDocument2 pagesTrigonometric Ratios: Find The Value of Each Trigonometric RatioRandom EmailNo ratings yet

- Community Organizing Philosophies of Addams and AlinskyDocument40 pagesCommunity Organizing Philosophies of Addams and AlinskymaadamaNo ratings yet

- MUSIC 7 Q3 W1D1 MoroIslamic Vocal MusicDocument2 pagesMUSIC 7 Q3 W1D1 MoroIslamic Vocal MusicAires Ichon100% (1)