Professional Documents

Culture Documents

PEJ Study Analyzes 2004 Election Coverage

Uploaded by

cute_aqoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

PEJ Study Analyzes 2004 Election Coverage

Uploaded by

cute_aqoCopyright:

Available Formats

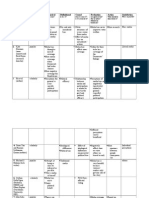

Content Analysis

1. Title of the study:

“A study by the Project for Excellence in Journalism and the Joan

Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy”

2. Proponent/ Researchers:

Stephen Farnsworth and Robert Lichter.

3. Statement of the Problem/ Sub-problems:

First, we identified what each story was about, topic. Next, we identified

the primary figure the story was focused around. Was it a particular candidate, a

group of candidates, or others? Third, we examined who was affected by what the

story was about, impact. Was it citizens? Politicians? Interest groups? Or a

combination? In addition to these measurements, the study also noted two other

features for each story. We considered what initiated the story, its trigger: Was it

something a candidate said or did? Something from a campaign surrogate? An

outsider? Or was the story initiated by journalistic enterprise? Finally, the study

measured the tone of each story. Within its frame, was the story predominantly

positive, negative or neutral about the candidates or their electoral prospects? In order

to fall into the positive or negative category, two-thirds or more of the assertions in a

story had to fall clearly on one side of that line or the other.

4. Assumption/ Hypothesis:

• Just five candidates have been the focus of more than half of all the coverage.

Hillary Clinton received the most (17% of stories), though she can thank the

overwhelming and largely negative attention of conservative talk radio hosts for

much of the edge in total volume. Barack Obama was next (14%), with

Republicans Giuliani, McCain, and Romney measurably behind (9% and 7% and

5% respectively). As for the rest of the pack, Elizabeth Edwards, a candidate

spouse, received more attention than 10 of them, and nearly as much as her

husband.

• Democrats generally got more coverage than Republicans, (49% of stories vs.

31%.) One reason was that major Democratic candidates began announcing their

candidacies a month earlier than key Republicans, but that alone does not fully

explain the discrepancy.

• Overall, Democrats also have received more positive coverage than Republicans

(35% of stories vs. 26%), while Republicans received more negative coverage

than Democrats (35% vs. 26%). For both parties, a plurality of stories, 39%, were

neutral or balanced.

• Most of that difference in tone, however, can be attributed to the friendly

coverage of Obama (47% positive) and the critical coverage of McCain (just 12%

positive.) When those two candidates are removed from the field, the tone of

coverage for the two parties is virtually identical.

• There were also distinct coverage differences in different media. Newspapers

were more positive than other media about Democrats and more citizen-oriented

in framing stories. Talk radio was more negative about almost every candidate

than any other outlet. Network television was more focused than other media on

the personal backgrounds of candidates. For all sectors, however, strategy and

horse race were front and center.

5. Research Methods used:

Qualitative Method is the method that used.

6. Summary of the Findings/ Conclusions and Recommendations:

The 2004 PEJ study examined theme-based stories, rather than all topics of election

coverage. Even here, in a narrowed range of stories, politics accounted for more than half

of the coverage.

Another study that focused on the primary campaign season was of network evening

television coverage in 2004 conducted by Stephen Farnsworth and Robert Lichter. Their

work showed an even higher percentage, 77%, of the primary season election stories

were focused on horse race issues and only 18% were focused on policy issues. Stephen

J. Farnsworth and S. Robert Lichter. 2007. The Nightly News Nightmare: Television’s

Coverage of U.S. Presidential Elections, 1988-2004. 2d ed. Lanham, MD: Rowman &

Littlefield.

Marion R. Just, Ann N. Crigler, Dean E. Alger, Timothy E. Cook, Montague Kern, and

Darrell M. West 1996, Crosstalk: Citizens, Candidates and the Media in a Presidential

Campaign. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1996.

<http://www.journalism.org/node/8191 January 20, 2011>

You might also like

- Political Communication & Strategy: Consequences of the 2014 Midterm ElectionsFrom EverandPolitical Communication & Strategy: Consequences of the 2014 Midterm ElectionsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Buying Reality: Political Ads, Money, and Local Television NewsFrom EverandBuying Reality: Political Ads, Money, and Local Television NewsNo ratings yet

- Out of The GateDocument35 pagesOut of The GateFadli NoorNo ratings yet

- The Gamble: Choice and Chance in the 2012 Presidential Election - Updated EditionFrom EverandThe Gamble: Choice and Chance in the 2012 Presidential Election - Updated EditionNo ratings yet

- Rushed to Judgment: Talk Radio, Persuasion, and American Political BehaviorFrom EverandRushed to Judgment: Talk Radio, Persuasion, and American Political BehaviorNo ratings yet

- Common Knowledge: News and the Construction of Political MeaningFrom EverandCommon Knowledge: News and the Construction of Political MeaningNo ratings yet

- Collusion: How the Media Stole the 2012 Election—and How to Stop Them from Doing It in 2016From EverandCollusion: How the Media Stole the 2012 Election—and How to Stop Them from Doing It in 2016No ratings yet

- The 2016 US Presidential Campaign Political Communication and Practice by Robert E. Denton JR (Eds.)Document342 pagesThe 2016 US Presidential Campaign Political Communication and Practice by Robert E. Denton JR (Eds.)Eirini SotiropoulouNo ratings yet

- True Blues: The Contentious Transformation of the Democratic PartyFrom EverandTrue Blues: The Contentious Transformation of the Democratic PartyNo ratings yet

- The Partisan Sort: How Liberals Became Democrats and Conservatives Became RepublicansFrom EverandThe Partisan Sort: How Liberals Became Democrats and Conservatives Became RepublicansNo ratings yet

- Richard L. Fox, Jennifer M. Ramos-iPolitics - Citizens, Elections, and Governing in The New Media Era-Cambridge University Press (2011)Document324 pagesRichard L. Fox, Jennifer M. Ramos-iPolitics - Citizens, Elections, and Governing in The New Media Era-Cambridge University Press (2011)xcuadra_1No ratings yet

- The Voter’s Guide to Election Polls; Fifth EditionFrom EverandThe Voter’s Guide to Election Polls; Fifth EditionNo ratings yet

- Public Opinion and Democratic Accountability: How Citizens Learn about PoliticsFrom EverandPublic Opinion and Democratic Accountability: How Citizens Learn about PoliticsNo ratings yet

- Stasis GridDocument4 pagesStasis Gridapi-302417803No ratings yet

- 6a. HANDOUT - Media - TechnologyDocument10 pages6a. HANDOUT - Media - TechnologyPepedNo ratings yet

- Media in Politics: An Analysis of The Media's Influence On VotersDocument6 pagesMedia in Politics: An Analysis of The Media's Influence On VotersTira J. MurrayNo ratings yet

- Hopes and Fears: Trump, Clinton, the voters and the futureFrom EverandHopes and Fears: Trump, Clinton, the voters and the futureNo ratings yet

- Echo Chambers and Partisan Polarization: Evidence From The 2016 Presidential CampaignDocument43 pagesEcho Chambers and Partisan Polarization: Evidence From The 2016 Presidential CampaignPaula GonzalezNo ratings yet

- The Timeline of Presidential Elections: How Campaigns Do (and Do Not) MatterFrom EverandThe Timeline of Presidential Elections: How Campaigns Do (and Do Not) MatterNo ratings yet

- The Race Card: Campaign Strategy, Implicit Messages, and the Norm of EqualityFrom EverandThe Race Card: Campaign Strategy, Implicit Messages, and the Norm of EqualityNo ratings yet

- A House Divided: What Would We Have to Give Up to Get the Political System We Want?From EverandA House Divided: What Would We Have to Give Up to Get the Political System We Want?No ratings yet

- Talk Radio’s America: How an Industry Took Over a Political Party That Took Over the United StatesFrom EverandTalk Radio’s America: How an Industry Took Over a Political Party That Took Over the United StatesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- The Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott WalkerFrom EverandThe Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott WalkerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (11)

- Talking Together: Public Deliberation and Political Participation in AmericaFrom EverandTalking Together: Public Deliberation and Political Participation in AmericaRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Learning While Governing: Expertise and Accountability in the Executive BranchFrom EverandLearning While Governing: Expertise and Accountability in the Executive BranchNo ratings yet

- News That Matters: Television and American Opinion, Updated EditionFrom EverandNews That Matters: Television and American Opinion, Updated EditionNo ratings yet

- The Trump Card: Rhetorical Strategies in The 2016 Presidential ElectionDocument17 pagesThe Trump Card: Rhetorical Strategies in The 2016 Presidential ElectionQuinton ThomasNo ratings yet

- U1-Lupu OliverosSchiumeriniDocument44 pagesU1-Lupu OliverosSchiumeriniLauritoNo ratings yet

- Political Communication Strategies in Post-Independence Jamaica, 1972-2006From EverandPolitical Communication Strategies in Post-Independence Jamaica, 1972-2006No ratings yet

- Jour 3796 PaperDocument9 pagesJour 3796 Paperapi-314087580No ratings yet

- Return of the "L" Word: A Liberal Vision for the New CenturyFrom EverandReturn of the "L" Word: A Liberal Vision for the New CenturyNo ratings yet

- The Politics of Evasion:: Democrats and The PresidencyDocument27 pagesThe Politics of Evasion:: Democrats and The Presidencymillian0987No ratings yet

- Half-Time!: American public opinion midway through Trump's (first?) term – and the race to 2020From EverandHalf-Time!: American public opinion midway through Trump's (first?) term – and the race to 2020No ratings yet

- Comparing Reception From TV CommercialsDocument23 pagesComparing Reception From TV CommercialsSupun GunarathneNo ratings yet

- Why Not Parties?: Party Effects in the United States SenateFrom EverandWhy Not Parties?: Party Effects in the United States SenateNathan W. MonroeNo ratings yet

- Marchal Et AlDocument7 pagesMarchal Et AlAmadon FaulNo ratings yet

- Laboratories against Democracy: How National Parties Transformed State PoliticsFrom EverandLaboratories against Democracy: How National Parties Transformed State PoliticsNo ratings yet

- A Virtuous Circle - Political Communications in Post-Industrial DemocraciesDocument359 pagesA Virtuous Circle - Political Communications in Post-Industrial Democraciescristina.sorana.ionescu6397No ratings yet

- Unstable Majorities: Polarization, Party Sorting, and Political StalemateFrom EverandUnstable Majorities: Polarization, Party Sorting, and Political StalemateNo ratings yet

- Follow the Leader?: How Voters Respond to Politicians' Policies and PerformanceFrom EverandFollow the Leader?: How Voters Respond to Politicians' Policies and PerformanceRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Effects of Political Advertising: OliticalDocument13 pagesEffects of Political Advertising: OliticalMuhib NoharioNo ratings yet

- The Financiers of Congressional Elections: Investors, Ideologues, and IntimatesFrom EverandThe Financiers of Congressional Elections: Investors, Ideologues, and IntimatesNo ratings yet

- The Agenda-Setting Function of Mass MediaDocument12 pagesThe Agenda-Setting Function of Mass MediaAmin HajNo ratings yet

- 9780472902699Document331 pages9780472902699allyNo ratings yet

- 1894 Morgan Report on Overthrow of Hawaiian KingdomDocument8 pages1894 Morgan Report on Overthrow of Hawaiian KingdomLinas KondratasNo ratings yet

- Malone POL 296N Lecture 1Document20 pagesMalone POL 296N Lecture 1cmalone410No ratings yet

- House Hearing, 105TH Congress - Independent Counsel ReportDocument127 pagesHouse Hearing, 105TH Congress - Independent Counsel ReportScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Plyler V Doe 1982Document7 pagesPlyler V Doe 1982api-412275167No ratings yet

- Electing The President of The United StatesDocument29 pagesElecting The President of The United Statesbobbynichols0% (1)

- Abstract: Abraham Lincoln's "House Divided" Speech Was Not A PredictionDocument20 pagesAbstract: Abraham Lincoln's "House Divided" Speech Was Not A PredictionalysonmicheaalaNo ratings yet

- Politics Disadvantage - Immigration Update - MSDI 2013Document9 pagesPolitics Disadvantage - Immigration Update - MSDI 2013Eric GuanNo ratings yet

- Biography of Ronald ReaganDocument9 pagesBiography of Ronald ReaganMatthew SimkoNo ratings yet

- Vaughn IndexDocument43 pagesVaughn IndexSamuel LevineNo ratings yet

- Republican National Committee Rules, Adopted 2008Document45 pagesRepublican National Committee Rules, Adopted 2008Soren DaytonNo ratings yet

- US Senator List R1Document2 pagesUS Senator List R1Michelle LaceyNo ratings yet

- Why I Support Todd McIntyre For RPM ChairDocument2 pagesWhy I Support Todd McIntyre For RPM Chairtodd_j_mcintyreNo ratings yet

- Top 150 US History Guide for Regents ExamDocument16 pagesTop 150 US History Guide for Regents ExamSam_Buchbinder_8615No ratings yet

- Ida BDocument3 pagesIda BSharon BakerNo ratings yet

- Home Rule in The United StatesDocument2 pagesHome Rule in The United StatesEmmanuel Jimenez-Bacud, CSE-Professional,BA-MA Pol SciNo ratings yet

- Presidents of USADocument6 pagesPresidents of USAbharatNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 - American Political CultureDocument7 pagesChapter 4 - American Political Culturelvkywrd0% (1)

- U.S. Civics TestDocument11 pagesU.S. Civics TestPopeyeKahnNo ratings yet

- APUSH Period 4 ReviewDocument3 pagesAPUSH Period 4 ReviewKylei CordeauNo ratings yet

- The Shape of Antigun AstroturfDocument1 pageThe Shape of Antigun AstroturfThePoliticalHatNo ratings yet

- 40 Acres and A MuleDocument20 pages40 Acres and A MuleTom ReedNo ratings yet

- Skull and Bones ChartDocument63 pagesSkull and Bones Chartjuliusevola1No ratings yet

- 10 Steps to Becoming LawDocument2 pages10 Steps to Becoming Lawmin gasuNo ratings yet

- The New Nation 1789-1800-1Document21 pagesThe New Nation 1789-1800-1Miguel RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Corporation Law Case Digests: ATTY. MA. LULU G. REYES S.Y. 2020-2021Document3 pagesCorporation Law Case Digests: ATTY. MA. LULU G. REYES S.Y. 2020-2021Dara EstradaNo ratings yet

- Rosa ParksDocument8 pagesRosa Parksapi-281881980No ratings yet

- Lincoln and The 13th Amendment QuestionsDocument3 pagesLincoln and The 13th Amendment Questionsapi-3318521310% (1)

- Sebastian de Jesus Torres Aquino - Jacksonian America AssignmentDocument8 pagesSebastian de Jesus Torres Aquino - Jacksonian America AssignmentSebastian TorresNo ratings yet

- A Working History of Education in The African World - EditedDocument7 pagesA Working History of Education in The African World - EditedMichael OmolloNo ratings yet

- GOP Insurrectionists in IndianaDocument12 pagesGOP Insurrectionists in IndianaMonte AltoNo ratings yet