Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Journalists' Safety: Involving Media Owners

Uploaded by

Center for Media Freedom & Responsibility0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

811 views46 pagesCMFR produced a monograph report on the issues of journalists’ safety, from the perspective of owners/their representatives. The report included discussions on how the owners see their responsibilities and their capacity to provide protection, the problems and what they perceive to be the most serious challenge to the protection of journalists.

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCMFR produced a monograph report on the issues of journalists’ safety, from the perspective of owners/their representatives. The report included discussions on how the owners see their responsibilities and their capacity to provide protection, the problems and what they perceive to be the most serious challenge to the protection of journalists.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

811 views46 pagesJournalists' Safety: Involving Media Owners

Uploaded by

Center for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityCMFR produced a monograph report on the issues of journalists’ safety, from the perspective of owners/their representatives. The report included discussions on how the owners see their responsibilities and their capacity to provide protection, the problems and what they perceive to be the most serious challenge to the protection of journalists.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 46

The Asia Foundation

Journalists’ Safery:

Involving Media Owners

Copyright * 2010

By the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility

‘This monograph is made possible by the generous support of the American people

through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The

‘contents are the responsibility of the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility

and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, the United States Government,

or The Asia Foundation,

ISBN 978-971-93724-8-6

All rights reserved. No part of this monograph may be reproduced in any form.

or by electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval

systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer

who may quote brief passages in a revi

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A grant from the United States Agency for International

Development (USAID) through The Asia Foundation made this

publication possible.

Melinda Quintos de Jesus and Luis V. Teodoro edited this

monograph. Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility staff

members Kathryn Roja G. Raymundo, Melanie Y. Pinlac, Martha

A. Teodoro, Rupert Francis D. Mangilit, Hector Bryant L, Macale,

and Alaysa Tagumpay E. Escandor provided research, initial

reports, and other editorial support.

Photos by Lito Ocampo.

Cover and layout design by Design Plus.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION .

More than the bottom line

Private ownership of medi 10

ROUNDTABLE DISCUSSION

ON MEDIA SAFETY 2010 oeccscccsssscsssssessesseesessneeresseeseeeee 15

The role of national associations ......sesssseereereeseesees 16

Landscape of impurity ...sseeesecsseecesseecentenenneersnneereenensesas 18

Legal awareness wausensievenessecsn-sssascesssesssasepessanecsseseeremeerseeee, LP

Safety principles ........ccccsssetesesssssesesesaseecceernnneecesennneeenss 20

Danger 2Omes map .-rssssssceecseessnescnreoneessneeanessneesseuaresanenen

Safety communication system

Impact of the discussions

Coordinating actions .

MEDIA DEFENSE AND SAFETY ...0.:sccsessessneessteeneeranee 35

THE VISAYAS EXPERIENCE......sesseessesonre

“Peanehal” cities szcscccisccosintavaennenntenieanee

Legal harassment .

Closure...

Engagement

Professionalism as protection .

A. Strong Press COMMUTIILY ..-.ssecsseceseeeseseeneteeeseseeseeesees AL

"THE MINDANAO EXPERIENGE ws.ccsssscscssssseesseassscansusssses 45

Asctarches cara tlie sees isscs teccessaa tesigtevonvasaseeaitencesnes 46

Protocols anid trainin pS ssessccccsscesssscsscernsveceruspsstossecsnevescne 47

Ganitlont siiticiiaaa neta derma: hahaniutieien mone: 40

Legal defense.....cssesccsssssvsseensesessseses

National effort,

Other effort:

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONSG.............51

MATRIX ON MEDIA OWNERSHIP......

Government-owned and -controlled media......

Members of national media associations .....:.seseseeonee 56

Philippine mass media and their Owners .........00:--se0ee 57

CMFR DATABASE ON THE KILLING OF

JOURNALISTS AND MEDIA WORKERS IN THE

PHILIPPINES SINCE 1986 .. a 69

THE PHILIPPINE JOURNALIST'S

CODE OF ETHICS .

3, ee

IMPUNITY:

It took 18 years from the fall of the Marcos

dictatorship for the issue of journalists’ safety to

become a central concern for the national media

rrr linia

Introduction

INTRODUCTION

More than the bottom line

THE SAFETY of journalists and media workers has been

an issue in the Philippines since the restoration of the institutions

and fundamentals of liberal democracy, including free expression

and press freedom, in 1986, when the 21-year-old government of

Ferdinand Marcos was overthrown by the civilian-military mutiny

known as EDSA 1.

Although the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility

(CMER) had started a database on killings in 1991, it took 18 years

from the fall of the Marcos dictatorship for the issue of journalists

safety to become a central concern for the mational media

community. In 2004, work-related killings spiked to seven. But for

the first time, a witness to a killing was willing to testify, and the

prospect of prosecuting the murder of broadcaster Edgar Damalerio

encouraged the creation of a network of media organizations and

press freedom advocacy groups in a national campaign against

impunity. The same network established the Freedom Fund for

Filipino Journalists Inc. (FFFJ) which focused on providing legal

and other assistance to besieged journalists and the families of the

slain, among other aims.

The dismantling of the Marcos government and Corazon

Aquino's assuming the presidency was followed within two months

by the killing of Reuters correspondent Willy Vicoy. Vicoy was

Press Freedom Protection and Journalists’ Safety:

A Media Community's Responsibility

killed while working in a conflict zone. By the end of Aquino's

six year term in 1992, 21 journalists had been killed in the line

of duty. CMFR's study of the cases established that the killings

were perpetrated by various groups and with varying motives. The

murders were a result in part of the unleashing of violent forces

following the end of military control, poor law enforcement, and

judicial corruption and delays. None of the cases had ever been

taken to court.

The killings continued during the term (1992-1998) of

Aquino's successor Fidel V. Ramos, although the number was less,

at 11. The short-lived administration of Joseph Estrada was no

exception, though "only" six journalists were killed between 1998

and 2001, when Estrada was removed from office by the popular

uprising known as EDSA 2.

Estrada was succeeded by Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, who not

only served the rest of Estrada’s six-year term from 2001 to 2004; she

also managed to remain in power after the 2004 elections, which she

claims to have won, until 2010. This turn of events made Arroyo

the longest serving President of the Philippines since Marcos.

In addition to over a thousand political activists killed, a record

79 journalists and media workers were also slain in the nine years of the

Arroyo watch, including 32 in the Ampatuan (Maguindanao) Massacre

of 2009, The end of Arroyo's term and the beginning of that of the

current President, Benigno Aquino IIL, in July, 2010, did not end the

killing of journalists. Radio broadcaster Miguel Belen was shot by an

assailant riding tandem on a motorcycle on July 9. Belen survived the

attack tnut died July 31:

‘The record number of political activists and journalists killed

during the nine years when Arroyo was in power has been explained

a

Introduction

as a consequence of both government policy (the killing of activists

was part of the anti-insurgency policy) as well as indifference. But in

the case of journalists the killings also occurred in the context of the

Arroyo government's anti-press and anti-media initiatives, which

included the filing of numerous libel suits, threats to withdraw

network franchises and to file charges of inciting to sedition against

some media organizations, and the inclusion of journalists’ groups

in the military’s dreaded Orders of Battle, which in effect authorize

the neutralization of the members of the groups listed.

Among the initiatives media organizations took in 2003, when

they recognized the need to do something about the killing of journalists,

was the founding by CMFR, the Center for Community Journalism

and Development, the Kapisanan ng mga Brodkaster ng Pilipinas (KBP,

Association of Broadcasters of the Philippines), Philippine Center for

Investigative Journalism (PCIJ), Philippine News, and the Philippine

Press Institute (PPT) of the FFFJ.

These groups, along with the National Union of Journalists

of the Philippines (NUJP), had been conducting safety and security

training. FFFJ had also identified media ethics as a necessary

component of journalist protection as good practice earns strong

community support and protection. Since then the campaign

against the culture of impunity that has encouraged the continuing

killing of journalists and media workers has been a key element

of the advocacies of a number of journalists’ and media advocacy

groups.

KBP and PPI, as organizations, represent the owners

of broadcast and print news organizations, respectively. But

beyond this institutional involvement, the owners of large media

corporations limit their protective measures only to their employees

and some of these measures were sometimes inadequate, especially,

Press Freedom Protection and Journalists" Safety:

A Media Community's Responsibility

for those working as correspondents and stringers. Most of the

owners of community news organizations cannot afford to provide

even minimal protection. CMFR found that few newsrooms even

conduct basic safety measures.

Private ownership of media

The development of the Philippine press, including radio

and television, had always been in the hands of private owners. But

the efforts of media advocacy and journalists’ groups have not been

supplemented or echoed by the corporations that own broadcast

networks and newspapers. And yet the private ownership of the

Philippine media has been an important factor in the way journalists

and media workers cover and comment on events.

Philippine media are not only privately owned; the corporations

that own them are also part of conglomerates with interests other than

broadcasting or publishing, In most cases these conglomerates also have

political interests, given the reality of state regulation over commercial

enterprises in the Philippines. But some media organizations have

direct political links in terms of their publishers’ being themselves

political players and even candidates for various offices including the

Presidency.

It’s a pattern established during the U.S. colonial period

(1900-1946), when political parties went into publishing as a means

of defending themselves against their political rivals as well as

an instrument in advancing their political interests. Eventually,

business interests also went into publishing, and expanded into

broadcasting after the Second World War.

The pattern has held till the present. The economic interests

of media owners have ranged from real estate to telecommunications

Introduction

to the hotel business, fast food franchises to shopping malls,

airlines and shipping to public utilities. Inevitably the defense and

advancement of these interests have helped shape media reporting,

commentary, and analysis. Although not all owners intervene in

the daily operations of their newspaper or broadcast network,

editors, and other decision makers are nevertheless well aware of

owner interests, and therefore, their probable preferences in the

coverage of an event or issue that’s likely to have an impact on the

business and/or political concerns of media owners.

The system of media ownership has made the public service

that the media are, privately owned and functioning for the defense

and enhancement of private interests, in which the bottom line,

or profitability, particularly in the broadcast networks, has been

shaping editorial policy. The bottom line is at the root of such media

problems as bias and lack of fairness, sensationalism, and the drive

for exclusives, which at times have put journalists in danger. In one

instance, a broadcaster's search for an exclusive in behalf of boosting

her network's ratings, for example, led to her and her camera crew's

being kidnapped by the kidnap-for-ransom Abu Sayyaf Group.

On the other hand, the broadcast organizations’ focus on

exclusivity has also led to airing stories which were later found

to be false. In the August 23 hostage-taking incident, the same

competitive environment led to one error after another which

contributed to its bloody outcome (eight hostages were killed).

But ordinary day-to-day reporting has also put journalists in

danger, particularly in environments where responsible journalism

compels journalists to report corruption, bad governance, and

criminal activity, as was the case with some 90 percent of those

journalists killed in the Philippines since 1986.

10

oT

Press Freedom Protection and Journalists’ Satety:

A Media Community's Responsibility

Most of the owners of the media have nevertheless been

remarkably aloof to the imperative of assuring the safety and security

of the staffs of their broadcast networks and newspapers. This must

change. The owners of the media must recognize that the safety of

those who assure them the profits that keep them in business, and

on whose skills depend the continued existence of radio and TV

networks as well as newspapers and online news sites, should be

their concern as it has been that of individual practitioners as well

as journalists’ and media advocacy groups.

This recognition can and should take specific forms, among

them providing with appropriate equipment and insurance those

journalists in dangerous areas and those who consent to cover

hazardous beats, making legal assistance available to journalists

in trouble, and holding safety training regularly, among others.

While providing journalists in hazardous beats or assignments

insurance, is among the precautions some media corporations have

taken, this practice must be standardized across the profession,

and must be supplemented by other measures. Those measures

and others are detailed in this monograph, which also includes

the recommendations to owners that the Cebu Citizens Press

Council has prepared so they can contribute to assuring the safety

of journalists.

Ethical and professional compliance, establishing journalist

networks, and gaining the respect of the communities, this

monograph also points out, are still among the approaches

necessary to put a stop to the continuing killing of journalists and

Introduction

media workers in the Philippines, These have been the staple of

the training provided by journalist and media advocacy groups

for years, But to these must be added the media owners’ assuming

greater responsibility for the safety of journalists and media workers

as well.

Press freedom and journalists’ safety require the

PURO M eS se eC Mena

but particularly that of the owners of media

Roundtable Discussion On Media Satety 2010

ROUNDTABLE DISCUSSION ON

MEDIA SAFETY 2010

THE CENTER for Media Freedom and Responsibility

(CMEFR) held a roundtable discussion on “Media Safety: Campaign

and Election Period 2010” last March 5 in Makati City to address

the need for safety measures of journalists covering campaign and

elections. The start of the campaign in February had raised threat

levels against journalists in a number of areas in the Philippines.

The purpose of the discussion was to promote awareness by the

press community of the safety mechanisms and means that can

be adapted for the greater protection of journalists and media

workers.

CMFR organized thiseventinc cooperation andin partnership

with the network of news organizations and media associations

of the Freedom Fund for Filipino Journalists (FFFJ), with grants

from the Open Society Foundation Media Program and the United

States Agency for International Development (USAID) through

The Asia Foundation (TAF)

Theculture of violence constitutesacontinuingthreatnotonly

against journalists. Periods of political tension, such as campaigns

and elections, raise levels of media activity. As the political story

unfolds, it invites press attention and coverage. As tensions increase,

how the press reports the claims and counterclaims of contending

political forces becomes a critical factor in how the public perceives

one side and the other. Journalists and media workers become

the targets of threats and attacks, even of assassinations. CMFR

prepared an agenda that would serve to consolidate the response of

media to heightened threats and attacks.

15

Press Freedom Protection and Journalists’ Safety:

A Media Community's Responsibility

CMEFR recognizes that press freedom protection and

journalists’ safety requires the involvement of the entire media

community, but particularly that of the owners of media

organizations. Several media-oriented non-governmental

organizations (NGOs) have focused on safety training. And quite

a number of journalists have attended these exercises. But it is the

media owners and their appointed managers who have a special

responsibility to establish internal and community-based systems

that enhance the security of their workers.

The sessions of the day’s programs identified safety and

protection strategies. Resource persons shared information with

media owners during the roundtable discussion. The RTD allowed

them and other members of the press community to exchange

views on the feasibility of adopting measures used in other places

to assist besieged journalists and prevent attacks and threats against

those covering the campaign and elections.

The role of national associations

To insure the participation of media owners in print and

broadcast, CMFR invited the current board members of the

Kapisanan ng mga Brodkaster ng Pilipinas (KBP, Association of

Broadcasters of the Philippines) and the Philippine Press Institute

(PPI), which represent the two largest national associations of

media owners and their appointed representatives.

There were 32 participants from Luzon, Visayas and

Mindanao including the staff of CMFR and the presenters.

Members of the PPI board of officers and trustees who came

to the meeting included: Isagani Yambot (Philippine Daily Inquirer);

Vergel Santos (BusinessWorld); Fr. Jonathan Domingo OMI

46

Roundtable Discussion On Media Safety 2010

(Mindanao Cross); Eden Estopace (The Philippine Star), representing

Antonio Katigbak; Jose Pavia (Mabuhay), Marlon Purificacion (The

Journal Group of Publications), representing Augusto Villanueva;

Juan Mercado (Press Foundation of Asia); Alban Quirino (Makiling

Journal); and Dalmacio Grafil (Leyte Samar Daily Express).

The members of the KBP board of directors and officers

who attended the discussion were: Ruperto Nicdao Jr. (Manila

Broadcasting Company); Herman Basbaiio (Bombo Radyo

Philippines); Lucky Paul Taruc (Radio Corporation of the

Philippines), representing Francis Cardona; Erwin Galang (GV

Broadcasting System/Mediascape Inc.); Rey Hulog (KBP executive

director); and Joselito Yabut (Primax Broadcasting System).

‘The members of the boards of the PPI and the KBP are

elected each year. PPI has 70 member organizations, KBP’s member

organizations include 143 television stations and 604 AM and FM

broadcast stations.

CMEFR invited Rowena Paraan of the National Union

of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP) who is in charge of the

International Federation of Journalists- NUJP Media Safety Office.

She is also a member of the NUJP board. Paraan shared how her

‘organization prepares media practitioners who cover dangerous

assignments. CMFR included her in the program so she could

inform the group what kind of safety training the NUJP will be

organizing for the election season, as some of NUJP members

belong to the organizations represented by KBP and PPI.

Other participants included representatives of various news

media organizations and members of the community press from

GMA-7, TV5, Sun.Star Cebu, and Cebu Daily News.

7

You might also like

- What Lies Beyond The InsurgencyDocument2 pagesWhat Lies Beyond The InsurgencyKyle RoxasNo ratings yet

- The Fifth Theory of Development CommunicationDocument15 pagesThe Fifth Theory of Development CommunicationJoshua RodilNo ratings yet

- The Cycle of Militarization, Demilitarization, and Remilitarization in The Early 21st Century Philippine SocietyDocument52 pagesThe Cycle of Militarization, Demilitarization, and Remilitarization in The Early 21st Century Philippine SocietyjcNo ratings yet

- Real Face FinalDocument68 pagesReal Face FinalKilusang Magbubukid ng PilipinasNo ratings yet

- International Church Groups' Statement Calling On UN Human Rights Council To Investigate Violations in PHDocument3 pagesInternational Church Groups' Statement Calling On UN Human Rights Council To Investigate Violations in PHRapplerNo ratings yet

- Digital Disinformation Threatens Philippine SocietyDocument3 pagesDigital Disinformation Threatens Philippine SocietyJoedel AlfonsoNo ratings yet

- Roots of The ConflictDocument3 pagesRoots of The ConflictSittie NeshreenNo ratings yet

- Valley Hot News Vol.2 No.08Document8 pagesValley Hot News Vol.2 No.08Philtian MarianoNo ratings yet

- Communist Party of The Philippines-New People's Army: Narrative SummaryDocument12 pagesCommunist Party of The Philippines-New People's Army: Narrative SummaryEthel MendozaNo ratings yet

- OACPA's Letter of Appeal To VERA Files Nov 18, 2022Document3 pagesOACPA's Letter of Appeal To VERA Files Nov 18, 2022VERA FilesNo ratings yet

- The Political Strategies of The Moro Islamic LiberDocument26 pagesThe Political Strategies of The Moro Islamic LiberArchAngel Grace Moreno BayangNo ratings yet

- UNRAVELING STORIES OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN LANAO DEL SUR, LANAO DEL NORTE, NORTH COTABATO AND MAGUINDANAO PROVINCES: A ReportDocument47 pagesUNRAVELING STORIES OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN LANAO DEL SUR, LANAO DEL NORTE, NORTH COTABATO AND MAGUINDANAO PROVINCES: A ReportMindanao Peoples' Peace MovementNo ratings yet

- IBP JournalDocument165 pagesIBP JournalArvin Antonio OrtizNo ratings yet

- For The Defense of Ancestral Domain and For Self DeterminationDocument3 pagesFor The Defense of Ancestral Domain and For Self DeterminationChra KarapatanNo ratings yet

- Motion For Partial Reconsideration (Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012)Document8 pagesMotion For Partial Reconsideration (Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012)Center for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- Justice Corona Position PaperDocument4 pagesJustice Corona Position PaperG Carlo TapallaNo ratings yet

- Suicide and The MediaDocument36 pagesSuicide and The MediaCenter for Media Freedom & Responsibility100% (1)

- My Personal Assessment On The Insurgency Situation in Negros Island - Sir ZamDocument4 pagesMy Personal Assessment On The Insurgency Situation in Negros Island - Sir ZamSalvador Dagoon JrNo ratings yet

- Ang Bayan, Aug 7, 2012Document11 pagesAng Bayan, Aug 7, 2012npmanuelNo ratings yet

- Tulfo Justice System The Effect of RaffyDocument6 pagesTulfo Justice System The Effect of RaffyMay MayNo ratings yet

- Part 1Document6 pagesPart 1HeheheheheeheheheheheNo ratings yet

- 1st A Reaction Paper To President Rodrigo Duterte FINALDocument1 page1st A Reaction Paper To President Rodrigo Duterte FINALLouieze Gerald GerolinNo ratings yet

- Essay About The Current Face of The Philippine Public AdministrationDocument4 pagesEssay About The Current Face of The Philippine Public Administrationzam fernandez100% (1)

- The Communist Party of The Philippines (CPP) Effects in The PhilippinesDocument2 pagesThe Communist Party of The Philippines (CPP) Effects in The PhilippinesChristian Mejia LunetaNo ratings yet

- State Press Releases and News Reports Re Hrvs Vs KMPDocument8 pagesState Press Releases and News Reports Re Hrvs Vs KMPKilusang Magbubukid ng PilipinasNo ratings yet

- CMFR Philippine Press Freedom Report 2010Document100 pagesCMFR Philippine Press Freedom Report 2010Center for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- Media On War On Drugs - A Study of The Media Coverage of The Duterte Administration's Campaign Against Illegal Drugs (CMFR)Document29 pagesMedia On War On Drugs - A Study of The Media Coverage of The Duterte Administration's Campaign Against Illegal Drugs (CMFR)Center for Media Freedom & Responsibility100% (2)

- Media On War On Drugs - A Study of The Media Coverage of The Duterte Administration's Campaign Against Illegal Drugs (CMFR)Document29 pagesMedia On War On Drugs - A Study of The Media Coverage of The Duterte Administration's Campaign Against Illegal Drugs (CMFR)Center for Media Freedom & Responsibility100% (2)

- Philippine Journalists' Safety GuideDocument74 pagesPhilippine Journalists' Safety GuideVERA FilesNo ratings yet

- Ibon Ccts Position Paper PaperDocument7 pagesIbon Ccts Position Paper PaperJZ MigoNo ratings yet

- Alaminos City Master Plan GoalsDocument40 pagesAlaminos City Master Plan GoalsKaren Joy Amada0% (1)

- Press Freedom in The Philippines - A Study in Contradictions (2004)Document87 pagesPress Freedom in The Philippines - A Study in Contradictions (2004)Center for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- PJR Reports September-October 2011Document2 pagesPJR Reports September-October 2011Center for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- Limited Protection - Press Freedom and Philippine LawDocument80 pagesLimited Protection - Press Freedom and Philippine LawCenter for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- Code of Ethics For Media (Book 1)Document34 pagesCode of Ethics For Media (Book 1)Center for Media Freedom & Responsibility100% (1)

- Philippine Press Freedom Primer (2007)Document20 pagesPhilippine Press Freedom Primer (2007)Center for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- Philippine Press Freedom Primer (2007)Document20 pagesPhilippine Press Freedom Primer (2007)Center for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- Guidelines To Protect Women From Discrimination in Media and Film (Book 2)Document20 pagesGuidelines To Protect Women From Discrimination in Media and Film (Book 2)Center for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- Rural Development Responses To COVID19Document21 pagesRural Development Responses To COVID19Nathaniel Vincent A. LubricaNo ratings yet

- Philippine Journalism Review August 2002Document5 pagesPhilippine Journalism Review August 2002Center for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- US Pushes Philippine Land Reform and Gets Nowhere - AR-47-53 PDFDocument0 pagesUS Pushes Philippine Land Reform and Gets Nowhere - AR-47-53 PDFBert M DronaNo ratings yet

- Mil Position PaperDocument3 pagesMil Position PaperBenedict riveraNo ratings yet

- Graft and CorruptionDocument24 pagesGraft and CorruptionpatriciaNo ratings yet

- Main Patterns of Philippine Foreign PolicyDocument24 pagesMain Patterns of Philippine Foreign PolicyAcuin Ma LeilaNo ratings yet

- Letter From OneNews Political Editor Ed Lingao Re: "Carpio Did NOT File Disqualification Petition vs. Marcos JR." ArticleDocument1 pageLetter From OneNews Political Editor Ed Lingao Re: "Carpio Did NOT File Disqualification Petition vs. Marcos JR." ArticleVERA FilesNo ratings yet

- PHILIPPINES MEDIA MARKET DESCRIPTIONDocument4 pagesPHILIPPINES MEDIA MARKET DESCRIPTIONZeno MartinezNo ratings yet

- PDAFDocument37 pagesPDAFeinel dc100% (1)

- Combating Fake News: An Agenda for Research and ActionDocument19 pagesCombating Fake News: An Agenda for Research and ActionOana Diana50% (2)

- Philippine Journalism Review (December 2002)Document6 pagesPhilippine Journalism Review (December 2002)Center for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- A Guide For Professional Journalism in Conflict Zones English PDFDocument60 pagesA Guide For Professional Journalism in Conflict Zones English PDFJamy MartínezNo ratings yet

- The-Rise-of-CPP-CHAPTER-1-and-2 4Document15 pagesThe-Rise-of-CPP-CHAPTER-1-and-2 4John Ruther DaizNo ratings yet

- Public Sector Corruption in Top Countries and Major Scandals in the PhilippinesDocument6 pagesPublic Sector Corruption in Top Countries and Major Scandals in the PhilippinesLEA MAE PACSINo ratings yet

- PNP and AFP VIOLATED THE RIGHTS OF AILEEN CRUZ, REY BUSANIA AND OFELIA INONG IN THEIR ILLEGAL ARREST AND DETENTION IN MT. PROVINCEDocument2 pagesPNP and AFP VIOLATED THE RIGHTS OF AILEEN CRUZ, REY BUSANIA AND OFELIA INONG IN THEIR ILLEGAL ARREST AND DETENTION IN MT. PROVINCEChra KarapatanNo ratings yet

- A Global Picture: Violence and Harassment Against Women in The News MediaDocument43 pagesA Global Picture: Violence and Harassment Against Women in The News MediaAndrew Richard ThompsonNo ratings yet

- JVO Winners and FellowsDocument34 pagesJVO Winners and FellowsCenter for Media Freedom & Responsibility100% (2)

- Technological Institute of the Philippines whistle-blower case studiesDocument6 pagesTechnological Institute of the Philippines whistle-blower case studiesStephany ChanNo ratings yet

- Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE) in One of The First Class City of LagunaDocument10 pagesDrug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE) in One of The First Class City of LagunaEisojPunsalanNo ratings yet

- The Philippine Peace Process: History, Profile and Status of Negotiations With The CPP-NDFP and The MILFDocument17 pagesThe Philippine Peace Process: History, Profile and Status of Negotiations With The CPP-NDFP and The MILFPatNo ratings yet

- Mapeh Learning Area Health 9 - Activity Sheet No. 1: Second Quarter SY 2020 - 2021Document1 pageMapeh Learning Area Health 9 - Activity Sheet No. 1: Second Quarter SY 2020 - 2021Ellyza SerranoNo ratings yet

- KMP Dispatch August 2019 Luzon de Facto Martial LawDocument4 pagesKMP Dispatch August 2019 Luzon de Facto Martial LawKilusang Magbubukid ng PilipinasNo ratings yet

- ECON 13 Reflection Paper No. 2 AY 2017 2018Document1 pageECON 13 Reflection Paper No. 2 AY 2017 2018Crimson PidlaoanNo ratings yet

- Sitrep 36 Marawi Crisis - 15 July 2017Document37 pagesSitrep 36 Marawi Crisis - 15 July 2017violeta_gloriaNo ratings yet

- Civil Liberties Restrictions and Media Control in Martial Law PhilippinesDocument14 pagesCivil Liberties Restrictions and Media Control in Martial Law PhilippinesliuggiuhNo ratings yet

- Guidelines On The Coverage of Crimes Against Women and MinorsDocument1 pageGuidelines On The Coverage of Crimes Against Women and MinorsCenter for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- Philippine Journalism Review December 1996Document53 pagesPhilippine Journalism Review December 1996Center for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- Philippine Journalism Review June-September 1992Document87 pagesPhilippine Journalism Review June-September 1992Center for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- Decision of The RTC Iriga City Branch 60 in The Miguel Belen Murder CaseDocument11 pagesDecision of The RTC Iriga City Branch 60 in The Miguel Belen Murder CaseCenter for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- Ampatuan, Maguindanao Massacre Primer (Updated November 22, 2019)Document12 pagesAmpatuan, Maguindanao Massacre Primer (Updated November 22, 2019)Center for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- PJR Reports - May 2005Document12 pagesPJR Reports - May 2005Center for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- Media Times 2015 (SAMPLE)Document13 pagesMedia Times 2015 (SAMPLE)Center for Media Freedom & Responsibility100% (1)

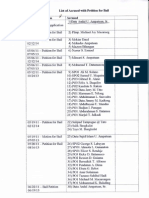

- Ampatuan (Maguindanao) Massacre Trial - List of Accused With Petitions For Bail (As of July 2014)Document2 pagesAmpatuan (Maguindanao) Massacre Trial - List of Accused With Petitions For Bail (As of July 2014)Center for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- Philippine Journalism Review - March 1995Document56 pagesPhilippine Journalism Review - March 1995Center for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- PJR Reports - April 2005Document16 pagesPJR Reports - April 2005Center for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- Ampatuan (Maguindanao) Massacre Trial - List of Arraigned Accused As of May 2014Document4 pagesAmpatuan (Maguindanao) Massacre Trial - List of Arraigned Accused As of May 2014Center for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- Media Times - Reporting Suicide: Hardly PainlessDocument6 pagesMedia Times - Reporting Suicide: Hardly PainlessCenter for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- MEDIATIMES 2013 - Media Mogulry ReduxDocument4 pagesMEDIATIMES 2013 - Media Mogulry ReduxCenter for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- MEDIATIMES 2013 - Pork and Plunder: Media in Aid of Public OutrageDocument8 pagesMEDIATIMES 2013 - Pork and Plunder: Media in Aid of Public OutrageCenter for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- CMFR Database On Media Affected by Typhoon YolandaDocument5 pagesCMFR Database On Media Affected by Typhoon YolandaCenter for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- MEDIATIMES 2013 - by The Numbers: Attacks and Threats Against The PressDocument5 pagesMEDIATIMES 2013 - by The Numbers: Attacks and Threats Against The PressCenter for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court's Decision On The Cybercrime LawDocument50 pagesSupreme Court's Decision On The Cybercrime LawJojo Malig100% (3)

- Media Times - Media's Responsibility: Disaster-Prone PhilippinesDocument6 pagesMedia Times - Media's Responsibility: Disaster-Prone PhilippinesCenter for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- CMFR Database On The Killing of Journalists As of May 30, 2015Document5 pagesCMFR Database On The Killing of Journalists As of May 30, 2015Center for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- Sandra Burton Nieman Fellowship For Filipino Journalists 2013Document8 pagesSandra Burton Nieman Fellowship For Filipino Journalists 2013Center for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- RE: Alleged Harassment at Dyok Aksyon RadyoDocument3 pagesRE: Alleged Harassment at Dyok Aksyon RadyoCenter for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- Media Times 2013 (SAMPLE)Document13 pagesMedia Times 2013 (SAMPLE)Center for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- New Guidelines For The Maguindano Multiple Murder TrialsDocument2 pagesNew Guidelines For The Maguindano Multiple Murder TrialsCenter for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- JVO Winners and FellowsDocument34 pagesJVO Winners and FellowsCenter for Media Freedom & Responsibility100% (2)

- Court of Appeals Resolution Affirmiming The Dismissal of Murder Charge Against Former GovernorDocument6 pagesCourt of Appeals Resolution Affirmiming The Dismissal of Murder Charge Against Former GovernorCenter for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- PCIJ - Check Corruption in Pork, Pass FOI Law For Citizens - 4 Sept 2013Document3 pagesPCIJ - Check Corruption in Pork, Pass FOI Law For Citizens - 4 Sept 2013Center for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- Senate Bill 1733Document13 pagesSenate Bill 1733Center for Media Freedom & Responsibility100% (1)