Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Earn Out Valuation

Uploaded by

pmk1978Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Earn Out Valuation

Uploaded by

pmk1978Copyright:

Available Formats

Accounting Across Borders

N.Y. Legislation Delivers Reform, Mobility IFRS on the Horizon

PLUS

Madoff Victims Tax Questions for 2008 Returns

C C O U N T I N G

& A U D business valuation

I T I N G

The Valuation of Earn-outs and Acquired Contingencies Under SFAS 141(R)

By Marc Asbra and Karen Miles

t the end of 2007, the FASB released SFAS 141(R), Business Combinations, which governs the financial accounting for mergers and acquisitions (M&A) that have closed on or after the first annual reporting period beginning on or after December 15, 2008. While SFAS 141(R) includes several minor changes to current GAAP, the treatment of certain items under SFAS 141(R) will dramatically affect the initial and subsequent recording of a transaction in the acquirers financial statements, and may even influence the structuring of certain deals. There are three critical provisions in SFAS 141(R) to consider: All forms of purchase consideration (including acquirer stock) are measured as of the acquisition date, the date at which the acquirer obtains control of the target. Transaction costs and related expenses (including restructuring expenses) are excluded from purchase consideration; the items are expensed as incurred. Earn-outs, other forms of contingent consideration, and certain acquired contingencies (assets and liabilities) are recorded at fair value as of the acquisition date. While the first and second items deserve attention in their own right, determining the fair value of contingent elements in a transaction will present new challenges to financial statement preparers. Valuation approaches and other issues related to earnouts and acquired contingencies must be considered.

Earn-outs

An earn-out can be a valuable device in structuring an M&A transaction, particularly when the buyer and seller have divergent views about the potential future success of the target company. Sellers seek compensation for future market opportuni-

ties they believe their business can exploit. Conversely, buyers are willing to pay for sustainable earnings and current achievements, but temper their expectations of yet-to-be-exploited opportunities. If structured properly, an earn-out can place the total transaction proceeds at a place on the risk-return spectrum that effectively balances the requirements of the buyer and the seller. The future payments give the seller an opportunity to realize more equity upside from the sale of the business, while at the same time providing the buyer with downside protection through the sellers strong interest in the success of the postcombination company. Under current GAAP, earn-out payments are recorded in the acquirers financial statements only if and when they are earned. Under SFAS 141(R), however, earn-out payments will be recorded at fair

value as of the acquisition date. As with many aspects of M&A negotiations, the elements and structure of an earn-out are limited only by the ability of the buyer and seller to think creatively about the future. Earn-outs can incorporate general or specific objectives, include financial or nonfinancial targets, contain single or multiple elements, cover short or long periods, and involve cash or other forms of consideration. Whether simple or complex, the forward-looking characteristics of earn-outs typically mean that the optimal method for quantifying their fair value is the income approach. The income approach generally estimates value by discounting expected future cash flows to the present through a rate of return (i.e., discount rate) that accounts for both the time value of money and investment risk factors. The determinaMARCH 2009 / THE CPA JOURNAL

38

tion of the fair value of an earn-out under this approach presents a number of challenges and prompts several questions: What is the likelihood that the earn-out will be achieved? What cash flows or other activities are directly associated with the earn-out? What is the level of risk in achieving the earn-out? What type of discount rate should be used in the analysis? How would that rate compare to the overall discount rate for other assets and liabilities being valued in the transaction? What adjustments are needed if the earn-outs are noncash? As one can imagine, the buyer and seller may have dramatically different opinions on these questions and the underlying issues. Similarly, divergent fair value conclusions can result from even small differences in the valuation assumptions used. Like all other fair value analyses done for acquisition accounting purposes, the valuation study for earn-outs must be thorough, supported by reasonable assumptions, and fully documented.

Example

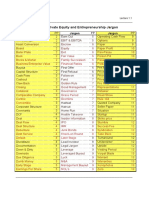

The following discussion focuses on the valuation of a relatively common earn-out based on the target business achieving cer-

tain thresholds of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA). The target company achieved $5 million in EBITDA on $25 million in sales in the year immediately prior to the transaction and presented a business plan to the buyer that demonstrated substantial future growth in revenue and profit. The buyer successfully negotiated the purchase of the target company for an initial price of $23 million, plus a three-year earn-out. Exhibit 1 shows that the earn-out is based on the buyers projected EBITDA levels and could result in the payment of an additional $4.5 million of consideration. The fair value of the earn-out, however, is determined to be approximately $3.3 million, or more than 25% below the nominal amount. The lower fair value results from the application of a 15% discount rate to capture the inherent risk that the target company will not achieve the projected EBITDA targets. Because of the relatively simple structure in this example, Exhibit 1 uses a single, likely scenario in determining the fair value of the earn-out. For more complex structures, an alternative analysis would utilize various projected scenarios and employ a probability-weighting scheme to estimate fair value. This alternative would provide flexibility in modeling the various future

events and assessing the potential earnout payments. Particular care needs to be exercised in constructing the probability weighting scheme, however, as the selection of probability factors can significantly affect the ultimate fair value conclusion. Care must also be taken to ensure that the financial projections utilized to determine the fair value of the earn-out are consistent with those used to estimate the fair values of the acquired intangible assets, which are often developed from similar income-based approaches. Not only is the determination of the fair value of an earn-out critically important for allocating the purchase price at the time of the transaction, but it is also significant for the acquirers future goodwill impairment testing. Exhibit 2 presents the implications of SFAS 141(R) as it relates to goodwill impairment testing. If the target business successfully achieves the earnout payments, the final amount of goodwill will actually be lower under SFAS 141(R) than it would under prior GAAP. This lower amount is placed on the acquirers balance sheet immediately, however, which may expose the acquirer to a higher likelihood of potential goodwill impairment charges in the event the earn-out targets are not achieved and the business experiences other challenges. The higher

EXHIBIT 1 Fair Value of Earn-out

Projected Seller Projections and Earn-out Sales EBITDA Earn-out Target EBITDA Earn-out Payments Income Approach Earn-out Payments Discount Period Discount Rate Present Value of Cash Flow Fair Valu e ( R ounded) 15.0% Actual $25,000 5,000 Year 1 $32,500 7,500 $7,500 1,000 Year 1 $1,000 1.0 0.870 $870 $3,300 Year 2 $40,000 10,000 $10,000 1,500 Year 2 $1,500 2.0 0.756 $1,134 Year 3 $47,500 12,500 $12,500 2,000 Year 3 $2,000 3.0 0.658 $1,315 Year 4 $0 4.0 0.572 $0 Year 4 $55,000 15,000

MARCH 2009 / THE CPA JOURNAL

39

amount of goodwill finally recorded under prior GAAP, in contrast, is placed on the balance sheet only after the earn-out targets have been reached. The payment of the earn-outs could indicate that the postcombination business is enjoying some degree of success, which might lessen the potential likelihood for goodwill impairment charges, all else being equal. Moreover, the amount of goodwill initially recorded under current GAAP provides a cushion to the acquirer in the event profit expectations do not materialize. That is, the probability of having a goodwill impairment charge is lower under prior GAAP because the goodwill related to the earn-out elements has not yet been placed on the balance sheet. Including the fair value of an earnout in the purchase price also has implications beyond financial reporting. Because valuation multiples implied from earn-out transactions under SFAS 141(R) will necessarily be higher than those under current GAAP, comparisons to prior transaction multiples or industry rules of thumb will require a more complicated analysis. To the extent an

earn-out represents a significant component of the purchase price, investors and analysts may pressure acquirer management teams for comprehensive disclosures regarding the nature of the earnout and the assumptions used to determine its fair value.

Acquired Contingencies

M&A transactions often include acquired contingencies on both sides of the target companys balance sheet: assets and liabilities. One of the more notable examples on the left-hand side is an indemnification asset, whereby the seller contractually indemnifies the acquirer for the outcome of a contingency or uncertainty related to all or part of a specific asset or liability. One of the more notable examples on the right-hand side is pending or threatened litigation. These and other contingencies are generally governed by SFAS 5, Accounting for Contingencies, which defines a contingency as an existing condition, situation, or set of circumstances involving uncertainty as to possible gain or loss to an entity that will ultimately be resolved

when one or more future events occurs or fails to occur. While SFAS 5 technically deals with assets (gains) and liabilities (losses), contingencies that might result in gains usually are not reflected on the balance sheet, since to do so might be to recognize revenue prior to its realization. As such, in practical terms, SFAS 5 deals mainly with the world of contingent liabilities. A contingent liability under SFAS 5 must meet two criteria: 1) it is probable that a liability had been incurred (or an asset had been impaired) at the measurement date; and 2) the amount of loss can be reasonably estimated. Current GAAP permits deferred recognition of acquired (pre-acquisition) contingencies until these recognition criteria are met. SFAS 141(R), however, has less stringent criteria in recognizing acquired contingencies and further segments between contractual and noncontractual contingencies. Specifically, contingent liabilities related to contracts (referred to as contractual contingencies) are measured at fair value as of their acquisition date. For all other noncontractual contingencies, the acquirer must recognize

EXHIBIT 2 Recording of Goodwill

Current GAAP Initial Purchase Price Earn-outs Total Transaction Value Net Tangible and Intangible Assets Goodwill $23,000 0 23,000 9,000 $14,000 Interim $ 0 4,500 4,500 Final $23,000 4,500 27,500 9,000 $18,500 SFAS 141(R) $23,000 3,300 26,300 9,000 $17,300 Difference $ 0 (1,200) (1,200) 0 ($1,200)

Current GAAP Purchase Price Earn-outs Total Transaction Value Net Tangible and Intangible Assets G oodwi l l Initial $ 23,000 0 $ 23,000 9,000 1 4 ,0 0 0 Interim $ 0 4,500 4,500 Final $ 23,000 $ 4,500 27,500 9,000 $ 1 8 ,5 0 0 SFAS 141(R) $ 23,000 3,300 26,300 9,000 $ 1 7 ,3 0 0 Difference $ 0 (1,200) (1,200) 0 ( $ 1 ,2 0 0 )

40

MARCH 2009 / THE CPA JOURNAL

a liability only if it is more likely than not (i.e., greater than 50%) that a liability exists at the acquisition date. SFAS 141(R) eliminates the condition that the liability be reasonably estimable. If it is deemed more likely than not, the noncontractual liability is recorded at fair value as of the acquisition date, consistent with the treatment of contractual contingencies. While the ultimate reality might be different, the presumption of most readers of SFAS 141(R) is that noncontractual contingencies will be identified and valued more frequently than under prior GAAP. Consider pending litigation as an example. While more complex models certainly exist, lawsuits and other contingent claims are often valued utilizing a decision-tree analysis. As the name suggests, a decision tree generally incorporates various future outcomes along as many potential branches as the user deems appropriate. As the branches diverge over time, probability factors are assigned at each of the nodes

representing the likelihood of each potential path occurring. In the case of a lawsuit or other financial claim, payment amounts are also estimated for the various outcomes. As illustrated below, the sum of the probability-weighted payment amounts serves as an indication of the fair value of the claim underlying the lawsuit. While this simple framework is useful in demonstrating an effective quantification technique, the valuation of a pending claim in the real world is more complex and requires thoughtful consideration and an analysis of the facts and circumstances of both the parties and the case. Other factors also warrant consideration, including expected legal costs and the time value of money, as well as the impact from the general disruption to the business and the diversion of managements time and attention during the litigation. The complexities of such analyses often prompt companies to seek outside assistance from lawyers and valuation spe-

cialists when developing reasonable and supportable fair value estimates. Public companies have the added sensitivity of financial statement disclosures related to acquired contingencies, which can greatly influence a companys legal strategy. SFAS 141(R) states that, for liabilities arising from contingencies, management should disclose the following: The amounts recognized at the acquisition date, or an explanation of why no amount was recognized. The nature of recognized and unrecognized contingencies. An estimate of the range of outcomes (undiscounted) for contingencies (recognized and unrecognized); if a range cannot be estimated, that fact and the reason behind it should be disclosed. SFAS 141(R) allows an acquirer in a transaction involving multiple acquired contingencies to aggregate disclosures for liabilities (and assets) arising from similar contingencies. While the aggregation of

Save The Date!

Valuation, Credit and Regulation: Practicing in the securities industry in todays environment.

Broker/ Dealer

Conference

Wednesday, May 13, 2009

New York Marriott Marquis Times Square 1535 Broadway, at 45th Street New York, NY 10036 Course Code: 25558911 Member Fee: $350 Nonmember Fee: $450 CPE Credit Hours: 8 Field of Study: Specialized Knowledge and Applications

foundation for accounting

Employee Benefits

Conference

Thursday, May 14, 2009 TOPICS TO INCLUDE: New York Helmsley Hotel I Whats new at the Department of Labor? 212 East 42nd Street I Impact of the economic New York, NY 10017 downturn on pension plans I Accounting and reporting pronouncements relating to pensions and other postretirement benefits I ERISA fiduciary matters I Nonqualified deferred compensation update for 2009

Course Code: 25621911 Member Fee: $350 Nonmember Fee: $450 CPE Credit Hours: 8 Field of Study: Advisory Services, Auditing, and Taxation For more information, visit www.nysscpa.org, or call 800-537-3635. Sign up for POP & save on this conference. To find out how, call 800-537-3635.

foundation for accounting

For more information, go to www.nysscpa.org, or call 800-537-3635.

FAE

education

Have You Signed Up for POP yet? Call 800-537-3635 to get yours today.

FAE

education

MARCH 2009 / THE CPA JOURNAL

41

information would limit the counterpartys ability to glean information about the lawsuit, the disclosure of any sensitive information is likely to be met with strong resistance by an acquirers management and legal counsel.

Increased Complexity

From a purely academic perspective, M&A transactions should be evaluated according to their underlying economics net present value, investment return, economic value added, or some other cash-flowbased financial metricand not judged by the financial statement impact caused by GAAP accounting requirements. M&A transactions are not completed in the classroom, however, and earnings-per-share figures are not ignored by investors. SFAS

141(R) will likely improve the consistency and transparency of financial reporting for M&A transactions, but it does so with the added cost of certain complexities, particularly as they relate to earn-outs and acquired contingencies. Management should be aware of the changes SFAS 141(R) represents, as it will be increasingly important to assess the initial and subsequent financial statement implications as early as possible when structuring an M&A transaction. The treatment of acquired contingent liabilities in SFAS 141(R) was the subject of significant debate leading up to its release. The FASB responded on December 15, 2008, with a proposed FASB Staff Position (FSP) that would amend SFAS 141(R) to require that contingent assets and liabilities be recognized

at fair value per SFAS 157, Fair Value Measurements, if the acquisition-date fair value can be reasonably determined. If the fair value cannot be reasonably determined, then the acquirer would follow the guidance set forth in SFAS 5. While the FSP had not been finalized at the time of this publication, if approved as currently drafted, the effect of the FSP would generally be a reversion back to current practice under SFAS 141 regarding acquired contingencies. Marc Asbra, CFA, is a a senior vice president in Houlihan Lokeys Los Angeles office. Karen Miles, CPA, heads Houlihan Lokeys financial opinions and advisory services business for Southern California.

EXHIBIT 3 Lawsuit Decision-Tree Analysis

Conditional Probabilities W i thdraw (1%)

Payment Nominal Probability Amount Weighted $0 $0

1%

L i ti gati on Claim

19%

Settl e

(19%)

$ 2 0 0 ,0 0 0

$ 3 8 ,0 0 0

80% Litigate

Win 40%

(80%) (40%)

$0

$0

25% 60% Lose 50%

High Damages

(80%) (60%) (25%)

$1,000,000

$120,000

Medium Damages 25%

(80%) (60%) (50%)

$500,000

$120,000

Low Damages

(80%) (60%) (25%) Total Expected Value

$250,000

$30,000 $308,000

42

MARCH 2009 / THE CPA JOURNAL

You might also like

- Earn Out Excel WorkingDocument2 pagesEarn Out Excel WorkingpremoshinNo ratings yet

- Corporate Finance NPV and IRR SolutionsDocument3 pagesCorporate Finance NPV and IRR SolutionsMark HarveyNo ratings yet

- CREFC CMBS 2 - 0 Best Practices Principles-Based Loan Underwriting GuidelinesDocument33 pagesCREFC CMBS 2 - 0 Best Practices Principles-Based Loan Underwriting Guidelinesmerlin7474No ratings yet

- Southland Case StudyDocument7 pagesSouthland Case StudyRama Renspandy100% (2)

- The Growing Importance of Fund Governance - ILPA Principles and BeyondDocument3 pagesThe Growing Importance of Fund Governance - ILPA Principles and BeyondErin GriffithNo ratings yet

- White Star Capital 2017 Canadian Venture Capital Landscape ReportDocument35 pagesWhite Star Capital 2017 Canadian Venture Capital Landscape ReportWhite Star CapitalNo ratings yet

- July 2014 Maglan Tearsheet Template (Long)Document2 pagesJuly 2014 Maglan Tearsheet Template (Long)ValueWalk100% (1)

- SBDC Valuation Analysis ProgramDocument8 pagesSBDC Valuation Analysis ProgramshanNo ratings yet

- Landfund Partners Ii, LP - Summary Term Sheet: StructureDocument1 pageLandfund Partners Ii, LP - Summary Term Sheet: StructureSangeetSindanNo ratings yet

- Real Estate InvestmentDocument18 pagesReal Estate InvestmentMpho Peloewtse TauNo ratings yet

- Mergers and Acquisitions Notes MBADocument24 pagesMergers and Acquisitions Notes MBAMandip Luitel100% (1)

- PIPE Investments of Private Equity Funds: The temptation of public equity investments to private equity firmsFrom EverandPIPE Investments of Private Equity Funds: The temptation of public equity investments to private equity firmsNo ratings yet

- MasDocument13 pagesMasHiroshi Wakato50% (2)

- Financial Reporting QuestionDocument5 pagesFinancial Reporting QuestionAVNEET SinghNo ratings yet

- Commercial Real Estate Valuation ModelDocument6 pagesCommercial Real Estate Valuation Modelkaran yadavNo ratings yet

- Negotiations, Deal StructuringDocument30 pagesNegotiations, Deal StructuringVishakha PawarNo ratings yet

- Crowd Real Estate Site TrackingDocument56 pagesCrowd Real Estate Site TrackingahgonzalezpNo ratings yet

- The Four Keys To Raising CapitalDocument6 pagesThe Four Keys To Raising CapitalMark OatesNo ratings yet

- CCMC InsurancePaper v2Document42 pagesCCMC InsurancePaper v2Sheila EnglishNo ratings yet

- Venture CapitalDocument10 pagesVenture CapitalgalatimeNo ratings yet

- Blackstone REIT Fact SheetDocument4 pagesBlackstone REIT Fact SheetchinaaffairsmonitorNo ratings yet

- Dilution Calculator Cap Table ModelDocument4 pagesDilution Calculator Cap Table ModelMichel KropfNo ratings yet

- Checklist For Structuring An AcquisitionDocument3 pagesChecklist For Structuring An AcquisitionMetz Lewis Brodman Must O'Keefe LLCNo ratings yet

- Private Equity Tax GuideDocument108 pagesPrivate Equity Tax GuidevinaymathewNo ratings yet

- Reg D For DummiesDocument51 pagesReg D For DummiesDouglas SlainNo ratings yet

- Business ValuationDocument5 pagesBusiness ValuationUmairHussain4943100% (7)

- SoDChecker Version0 4Document45 pagesSoDChecker Version0 4ravin.jugdav678No ratings yet

- Distribution Waterfall - Four ExamplesDocument14 pagesDistribution Waterfall - Four ExamplesShashankNo ratings yet

- Lecture 5 - A Note On Valuation in Private EquityDocument85 pagesLecture 5 - A Note On Valuation in Private EquitySinan DenizNo ratings yet

- Note On Angel InvestingDocument18 pagesNote On Angel InvestingSidakachuntuNo ratings yet

- Valuation For StartupsDocument39 pagesValuation For StartupsrabiadzNo ratings yet

- Report On Regulation A+ PrimerDocument13 pagesReport On Regulation A+ PrimerCrowdFunding BeatNo ratings yet

- Nda PDFDocument28 pagesNda PDFmy009.tkNo ratings yet

- Pro Forma Models - StudentsDocument9 pagesPro Forma Models - Studentsshanker23scribd100% (1)

- Private Equity Strategies: by Ascanio RossiniDocument18 pagesPrivate Equity Strategies: by Ascanio RossiniTarek OsmanNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 1 AnswersDocument4 pagesTutorial 1 AnswersBee LNo ratings yet

- CVNA Investment Memo SSP PDFDocument100 pagesCVNA Investment Memo SSP PDFTimothyNgNo ratings yet

- All 60 Startups That Launched at Y Combinator Winter 2016 Demo Day 1 - TechCrunchDocument50 pagesAll 60 Startups That Launched at Y Combinator Winter 2016 Demo Day 1 - TechCrunchAnonymous f9Zj4lNo ratings yet

- Earnout ValuationDocument5 pagesEarnout Valuationveda20100% (1)

- Private Equity FundDocument19 pagesPrivate Equity FundClint AyersNo ratings yet

- Real Estate Debt Due Diligence 2016Document17 pagesReal Estate Debt Due Diligence 2016Shahrani KassimNo ratings yet

- Sniders Corporate Tax Notes OUTLINEDocument166 pagesSniders Corporate Tax Notes OUTLINEMaggie ZalewskiNo ratings yet

- Five Steps To Valuing A Business: 1. Collect The Relevant InformationDocument7 pagesFive Steps To Valuing A Business: 1. Collect The Relevant InformationArthavruddhiAVNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Investment Principles and ChecklistsDocument147 pagesComprehensive Investment Principles and ChecklistsmeenasureshkNo ratings yet

- Realestate Firpta Us White PaperDocument20 pagesRealestate Firpta Us White PaperRoad AmmonsNo ratings yet

- Case Study PP 2Document42 pagesCase Study PP 2Anil BambuleNo ratings yet

- VC Evaluating BusinessDocument14 pagesVC Evaluating BusinessAvanish Nagar 23No ratings yet

- Buy-Side ProcessDocument8 pagesBuy-Side ProcessDaniel AhijadoNo ratings yet

- Preqin Compensation and Employment Outlook Private Equity December 2011Document9 pagesPreqin Compensation and Employment Outlook Private Equity December 2011klaushanNo ratings yet

- Reverse Discounted Cash FlowDocument11 pagesReverse Discounted Cash FlowSiddharthaNo ratings yet

- Rental Home Financial Projection TemplateDocument61 pagesRental Home Financial Projection TemplateMinh NguyenNo ratings yet

- Sample DCF Valuation TemplateDocument2 pagesSample DCF Valuation TemplateTharun RaoNo ratings yet

- Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania Bloomberg Navigation GuideDocument71 pagesBloomsburg University of Pennsylvania Bloomberg Navigation Guideseng086100% (1)

- Federal Taxation I - W AnswersDocument8 pagesFederal Taxation I - W AnswersGracie Ortuoste0% (1)

- Next Edge Private Lending Presentation v1Document16 pagesNext Edge Private Lending Presentation v1dpbasicNo ratings yet

- Credit Rating: Submitted by Shahnas A S4, MBA (IB)Document30 pagesCredit Rating: Submitted by Shahnas A S4, MBA (IB)Shahnas AmirNo ratings yet

- Private AcquisitionsDocument53 pagesPrivate AcquisitionsAleyna YılgınNo ratings yet

- Edelweiss Alpha Fund - November 2016Document17 pagesEdelweiss Alpha Fund - November 2016chimp64No ratings yet

- Private Equity JargonDocument14 pagesPrivate Equity JargonWilling ZvirevoNo ratings yet

- The Executive Guide to Boosting Cash Flow and Shareholder Value: The Profit Pool ApproachFrom EverandThe Executive Guide to Boosting Cash Flow and Shareholder Value: The Profit Pool ApproachNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument36 pagesCase StudyAhmed HadiNo ratings yet

- AJG Marine P&I Commercial Market Review September 2015Document94 pagesAJG Marine P&I Commercial Market Review September 2015sam ignarskiNo ratings yet

- Basis of Difference Balance of Trade (BOT)Document3 pagesBasis of Difference Balance of Trade (BOT)johann_747No ratings yet

- CPA Quizzer v.1 by Themahatma (CPAR 2016)Document9 pagesCPA Quizzer v.1 by Themahatma (CPAR 2016)John Mahatma Agripa100% (1)

- Mutual FundsDocument29 pagesMutual FundsVinay SinghNo ratings yet

- Subprime Mortgage CrisisDocument35 pagesSubprime Mortgage CrisisParaggNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Mutual Fund & Portfolio Management in Mutual Fund For Motilal Oswal Securities by Kalpa KabraDocument59 pagesAnalysis of Mutual Fund & Portfolio Management in Mutual Fund For Motilal Oswal Securities by Kalpa KabravishalbehereNo ratings yet

- Cocofed vs. Republic: LegisDocument4 pagesCocofed vs. Republic: LegisJoshua ManaloNo ratings yet

- History of The Company ActDocument13 pagesHistory of The Company ActJyoti SharmaNo ratings yet

- Strategic AlliancesDocument22 pagesStrategic AlliancesAngel Anita100% (2)

- Business Environment and Policy: Dr. V L Rao Professor Dr. Radha Raghuramapatruni Assistant ProfessorDocument41 pagesBusiness Environment and Policy: Dr. V L Rao Professor Dr. Radha Raghuramapatruni Assistant ProfessorRajeshwari RosyNo ratings yet

- 20170509r3q491 PDFDocument33 pages20170509r3q491 PDFAbraham ChongNo ratings yet

- Crash MysoreDocument40 pagesCrash MysoreyashbhardwajNo ratings yet

- History of DerivativesDocument29 pagesHistory of Derivativeshanunesh100% (1)

- How To Buy and Sell StockDocument9 pagesHow To Buy and Sell StockwaelNo ratings yet

- FFMC Rbi DocsDocument51 pagesFFMC Rbi DocsManikNo ratings yet

- Case AnalysisDocument6 pagesCase AnalysisAJ LayugNo ratings yet

- Business Environment 1-50Document50 pagesBusiness Environment 1-50Christine Mwamba ChiyongoNo ratings yet

- 12 - MWS96KEE127BAS - 1research Project - WalmartDocument7 pages12 - MWS96KEE127BAS - 1research Project - WalmartashibhallauNo ratings yet

- Capital Budgeting MathsDocument2 pagesCapital Budgeting MathsAli Akand Asif67% (3)

- Dabhol Case Study1Document28 pagesDabhol Case Study1Abhishek PandeyNo ratings yet

- R&R 2014 AccountsDocument78 pagesR&R 2014 AccountsBadGandalfNo ratings yet

- Pre RemovalExamination20192ndSemDocument13 pagesPre RemovalExamination20192ndSemLay Ann AlmarezNo ratings yet

- RespMemo - NUJS HSFDocument36 pagesRespMemo - NUJS HSFNarayan GuptaNo ratings yet

- Befa Unit IVDocument12 pagesBefa Unit IVNaresh Guduru93% (15)

- QIM - HFM WeekDocument3 pagesQIM - HFM WeekmikekcauNo ratings yet

- Thesis On System Analysis and DesignDocument68 pagesThesis On System Analysis and DesignAnna Rose Mahilum LintagNo ratings yet

- Allen Stanford Criminal Trial Transcript Volume 11 Feb. 6, 2012Document317 pagesAllen Stanford Criminal Trial Transcript Volume 11 Feb. 6, 2012Stanford Victims CoalitionNo ratings yet