Professional Documents

Culture Documents

LWR Ex 04 26

Uploaded by

Edi SiswantoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

LWR Ex 04 26

Uploaded by

Edi SiswantoCopyright:

Available Formats

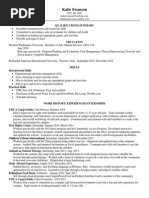

Integrated Analysis of Hybrid Systems for Rural Electrification in Developing Countries

Timur Gl

Supervisor and Examiner Assoc. Professor Jan-Erik Gustafsson Division of Land and Water and Water Resources Engineering Royal Institute of Technology

Supervisor in Germany Dr. Dirk Amann Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment, Energy

Reviewer Michael Bartlett Department of Energy Processes Royal Institute of Technology Stockholm 2004

TRITA-LWR Master Thesis ISSN 1651-064X LWR-EX-04-26

Abstract

Abstract

Around 2 billion people world-wide do not have access to electricity services, of which the main share in rural areas in developing countries. Due to the fact that rural electricity supply has been regarded as essential for economic development during the Earth Summit on Sustainable Development in 2002, it is nowadays a main focus in international development cooperation. Renewable energy resources are a favourable alternative for rural energy supply. In order to handle their fluctuating nature, however, hybrid systems can be applied. These systems use different energy generators in combination, by this maintaining a stable energy supply in times of shortages of one the energy resources. Main hope attributed to these systems is their good potential for economic development. This paper discusses the application of hybrid systems for rural electrification in developing countries by integrating ecological, socio-economic and economic aspects. It is concluded that hybrid systems are suitable to achieve both ecological and socio-economic objectives, since hybrid systems are an environmental sound technology with high quality electricity supply, by this offering a good potential for economic development. However, it is recommended to apply hybrid systems only in areas with economic development already taking place in order to fully exploit the possibilities of the system. Moreover, key success factors for the application of hybrid systems are discussed. It is found that from a technical point of view, appropriate maintenance structures are the main aspect to be considered, requiring the establishment of maintenance centres. It is therefore recommendable to apply hybrid systems in areas with a significant number of villages, which are to be electrified with these systems, in order to improve financial sustainability of these maintenance centres. The appropriate distribution model is seen as being important as well; it is thought that the sale of hybrid systems via credit, leasing or cash is the most likely approach. In order to do so, however, financial support and capacity building of local dealers is inalienable.

Table of Contents

II

Table of Contents

Abstract ........................................................................................................................I Table of Contents....................................................................................................... II List of Figures ........................................................................................................... IV List of Tables.............................................................................................................. V Acronyms .................................................................................................................. VI 1 1.1 1.2 2 Introduction ..................................................................................................... 1 Objective ........................................................................................................... 2 Methodology...................................................................................................... 2 Technologies for Rural Energy Supply ........................................................... 4

2.1 Decentralised Electrification .............................................................................. 4 2.1.1 Diesel Generating Sets ....................................................................................... 4 2.1.2 Renewable Energy Technologies ....................................................................... 5 2.2 2.2.1 2.2.2 2.2.3 2.2.4 2.3 3 Hybrid System Technology................................................................................ 6 Relevance .......................................................................................................... 6 Hybrid Systems in Developing Countries........................................................... 7 Other Hybrid Systems........................................................................................ 9 Technical Aspects ............................................................................................ 11 Grid-based Electrification ................................................................................ 14 Analysis of Impacts ........................................................................................ 16

3.1 Scope of the Analysis....................................................................................... 16 3.1.1 Scenario Definitions......................................................................................... 16 3.1.2 Modelling Assumptions ................................................................................... 18 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.4.1 3.4.2 3.4.3 The Concept of Indicators of Sustainability...................................................... 18 Developing an Indicator Set for Energy Technologies...................................... 19 Analysis of Sustainability ................................................................................ 21 Ecological Dimension ...................................................................................... 21 Socio-Economic Dimension............................................................................. 27 Economic Dimension....................................................................................... 33

3.5 Results and Discussion..................................................................................... 42 3.5.1 Results ............................................................................................................. 42 3.5.2 Discussion ....................................................................................................... 45

Table of Contents

III

Project Examples ........................................................................................... 47

4.1 Hybrid Systems in Indonesia............................................................................ 47 4.1.1 Baseline ........................................................................................................... 47 4.1.2 Project Description .......................................................................................... 47 4.2 4.2.1 4.2.2 4.2.3 5 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 6 Hybrid Systems in Inner Mongolia................................................................... 49 Baseline ........................................................................................................... 49 Project Description .......................................................................................... 49 Aspects of System Dissemination .................................................................... 52 Key success factors......................................................................................... 53 Organisation .................................................................................................... 53 Financing ......................................................................................................... 57 Capacity Building ............................................................................................ 60 Technical Aspects ............................................................................................ 62 Assessment of Electricity Demand and Potential for Renewable Energies........ 63 Political Factors ............................................................................................... 64 Summary and Conclusions ............................................................................ 66

Annex A: Electricity Demand and System Design................................................... 68 A.1 Calculation of Electricity Demand........................................................................ 68 A.2 System Design ..................................................................................................... 70 Annex B: GEMIS Scenario Calculations ................................................................. 75 B.1 Scenario Definitions ............................................................................................. 75 B.2 Modelling Results ................................................................................................ 79 Annex C: Analysis of Impacts .................................................................................. 86 C.1 Ecology................................................................................................................ 86 C.2 Socio-Economic Issues......................................................................................... 87 C.3 Economic Issues................................................................................................... 93 Annex D: Cost Analysis .......................................................................................... 101 D.1 Investment Costs................................................................................................ 104 D.2 Electricity Generating Costs............................................................................... 105 D.3 Electricity Generating Costs from Different Sources .......................................... 110 Terms of Reference ................................................................................................. 113

List of Figures

IV

List of Figures

Figure 2.1 Principle Circuit of Hybrid Systems ............................................................. 8 Figure 3.1 GEMIS Results: Greenhouse Gas Emissions .............................................. 22 Figure 3.2 Comparative Assessment of GHG Emissions ............................................. 23 Figure 3.3 GEMIS Results: Emissions of Air Pollutants.............................................. 23 Figure 3.4 Comparative Assessment of Air Pollutants Emissions ................................ 24 Figure 3.5 GEMIS Results: Cumulative Energy Demand of Primary Energy .............. 25 Figure 3.6 Comparative Assessment of Resource Consumption .................................. 25 Figure 3.7 Comparative Assessment of Noise Pollution .............................................. 26 Figure 3.8 Comparative Assessment of Cultural Compatibility and Acceptance .......... 28 Figure 3.9 Comparative Assessment of Supply Equity ................................................ 29 Figure 3.10 Comparative Assessment of Participation and Empowerment................... 30 Figure 3.11 Comparative Assessment of Potential for Economic Development .......... 31 Figure 3.12 Comparative Assessment of Employment Effects..................................... 32 Figure 3.13 Comparative Assessment of Impacts on Health ........................................ 33 Figure 3.14 Comparative Assessment of Investment Costs......................................... 36 Figure 3.15 Electricity Generating Costs in Comparison ............................................. 37 Figure 3.16 Comparative Assessment of Electricity Generating Costs......................... 38 Figure 3.17 Comparative Assessment of Maintenance Requirements .......................... 39 Figure 3.18 Comparative Assessment Regional Self-Supply and Import Independence 40 Figure 3.19 Comparative Assessment of Supply Security............................................ 41 Figure 3.20 Comparative Assessment of Future Potential............................................ 42 Figure 3.21 Results Ecology Assessment .................................................................... 43 Figure 3.22 Results Socio-Economic Assessment ....................................................... 44 Figure 3.23 Results Economic Assessment ................................................................. 44 Figure 5.1 Hybrid Village Systems: Distribution Steps ............................................... 60 Figure B.1 GEMIS Results: GHG Emissions .............................................................. 80 Figure B.2 GEMIS Results: Methane Emissions ......................................................... 81 Figure B.3 GEMIS Results: Air Pollutants .................................................................. 83 Figure B.4 Selected Air Pollutants .............................................................................. 84 Figure B.5 Cumulative Energy Demand (Primary Energy).......................................... 85 Figure B.6 Cumulative Energy Demand According to Resources................................ 85 Figure D.1 Specific Investment for Wind Power Plants and Diesel Gensets .............. 103 Figure D.2 Specific Investment for Hybrid Systems of Different Capacities.............. 104 Figure D.3 Illustration of Electricity Generating Costs for PV/Diesel........................ 108 Figure D.4 Illustration of Electricity Generating Costs for Wind/Diesel .................... 108

List of Tables

List of Tables

Table 3.1 Scenarios and Technologies for Rural Electrification................................... 16 Table 3.2 Criteria and Indicators for the Assessment of Energy Technologies ............. 19 Table 3.3 Performance Assessment Scheme................................................................ 20 Table 3.4 Main Assumptions for the Cost Analysis ..................................................... 34 Table 3.5 Specific Investment Costs of Hybrid Systems.............................................. 35 Table 3.6 Investment Costs of Different Scenarios for Rural Electrification ................ 36 Table 3.7 Electricity Generating Costs for Different Scenarios.................................... 38 Table 4.1 Hybrid Systems in Inner Mongolia .............................................................. 49 Table A.1 Standard Household Characteristics............................................................ 68 Table A.2 Rich Household Characteristics .................................................................. 68 Table A.3 Peak and Base Loads for Different Village Sizes ........................................ 69 Table A.4 Main Modelling Assumptions..................................................................... 70 Table A.5 Share of Technologies for Electricity Generation........................................ 71 Table B.1 Amount of Greenhouse Gas Emissions ....................................................... 80 Table B.2 Air Pollutants.............................................................................................. 82 Table B.3 Cumulative Energy Demand (Primary Energy) ........................................... 84 Table C.1: Initial Investment Costs for Diesel Gensets................................................ 93 Table C.2: Electricity Generating Costs for Diesel Gensets ......................................... 95 Table C.3: Hybrid Systems at Different Diesel Prices ................................................. 96 Table D.1 Main Assumptions for the Cost Analysis .................................................. 101 Table D.2 Investment Costs for Small-Scale Wind Power Plants............................... 102 Table D.3 Investment Costs for Diesel Gensets......................................................... 102 Table D.4 Range of Investment Costs for Hybrid Systems ........................................ 105 Table D.5 Electricity Generating Costs of PV/Diesel Systems [/kWh]..................... 106 Table D.6 Electricity Generating Costs of Wind/Diesel Systems [/kWh] ................. 106 Table D.7 Electricity Generating Costs PV/Wind...................................................... 109 Table D.8 Investment and Operating Costs of Different Household Systems, Inner Mongolia....................................................................................................... 111 Table D.9 Electricity Generating Costs of Hybrid Systems in Inner Mongolia .......... 111 Table D.10 5 kW Hybrid Systems at Different Diesel Prices ..................................... 112

Acronyms

VI

Acronyms

AC CED CSD DC EMS GEF GHG GTZ KfW OECD PV Schueco SMA SHS WHO Alternating Current Cumulative Energy Demand Commission on Sustainable Development Direct Current Energy Management System Global Environmental Facility Greenhouse Gas Deutsche Gesellschaft fr Technische Zusammenarbeit Kreditanstalt fr Wiederaufbau Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Photovoltaic Schueco International KG, produces i.e. different solar energy systems SMA Regelsysteme GmbH, produces i.e. inverters Solar Home System World Health Organisation

1 Introduction

Introduction

Recent research on the development of the worlds energy state and the future development scenarios show alarming developments: 1. Around 2 billion people world-wide do not have access to modern energy services. This lack of access to electricity mainly applies to rural areas in developing countries, and progress being made over the last 25 years has applied mainly to urban areas (The World Bank, 1996a). 2. Without states taking heavy financial initiatives, the situation in 2030 will remain more or less unchanged with 1.4 billion people or 18 % of the worlds population without electricity supply (IEA, 2002). 3. Global consumption of primary energy resources, however, is likely to increase, with the increase being mainly based on fossil fuels. Developing countries, especially in Asia, will account for more than 60 % of this increase (IEA, 2002). The effect of increasing global CO2-emissions will be the consequence. In response to the lack of electricity supply in developing countries, their improved access to modern energy services has been regarded as essential for sustainable development during the Earth Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg, 2002. This is mainly due to the goals that are associated with the development of energy infrastructure, major ones being economic and social goals. The outstanding key role in economic development, which had been attributed to energy services in the past, could not live up to experiences. Today, energy services are indeed seen as a major driving force to economic development, but additional measures are required as well. Higher availability of jobs, productivity increases or improved economic opportunities, however, are the effect that can be expected from better energy services, i.e. by catalysing the creation of small enterprises or livelihood activities in evening hours (WEHAB Working Group, 2002). Social benefits related to improved energy services include poverty alleviation by changing energy use patterns in favour of non-traditional fuels; the combating population growth by shifting relative benefits and costs of fertility towards lower rates of birth; and the creation of new opportunities for women by reducing the time for the collection of wood for cooking and heating (WEHAB Working Group, 2002), which is a major occupation of women in developing countries; time that could be used for education or employment instead. The challenge, thus, is to improve access to modern energy services, without on the other hand increasing reliance on fossil fuels. Recent approaches meet this challenge with a focus on decentralised systems for the electrification of rural areas. Main hope is here attributed to the application of renewable energies as wind, solar and hydro power, which are especially suited for decentralised electricity generation. Renewable energies use environmentally sound technologies: their consumption does not result in the depletion of resources; the compatibility to climate is better than for currently used options; and their application strengthens the security of energy supply by using local resources. A major problem related to the application of renewable energies in decentralised systems, however, is the instable energy provision due to the fluctuating nature of the resources. A pos-

1 Introduction

sibility to solve this problem is to backup the renewable energy generator with another power generator in a so-called hybrid system. This approach, although being known for quite some years already, is just now stepwise gaining importance. A number of projects applying hybrid systems for electricity generation have already been carried out, several are currently under implementation. However, the question whether and to which extent these systems satisfy the expectations on rural electrification projects with regard to sustainable development, has not been investigated yet and shall be matter of this paper.

1.1

Objective

The objective of this paper is to analyse and assess the sustainability of the application of hybrid systems for rural electrification in developing countries. Due to the absence of respective surveys, this analysis is performed in comparative terms on the basis of an indicator set developed here. The sustainability of hybrid systems is assessed relative to the other potential decentralised electrification scenarios: diesel generator-based mini-grids, Solar Home Systems and biogas plants for electricity generation. Moreover, the extension of the conventional grid is considered as well. Another objective here is to find key success factors for the application of hybrid systems. These key success factors are related to aspects of financing, organisation, capacity building and others, which are of importance for any decentralised rural electrification project and especially for hybrid systems. The objective in investigating key success factors is to maintain the sustainability of a project for rural electrification with hybrid systems, accepting that sustainability is an ongoing dynamic process, which needs to be ensured by setting the right framework.

1.2

Methodology

To pursue the above objectives, a literature research was performed first. The findings of this research were then discussed with project developers at the fair Intersolar in Freiburg/Germany on June, 28th, 2003, as well as with experts from Kreditanstalt fr Wiederaufbau (KfW) on July, 7th, 2003, and Deutsche Gesellschaft fr Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) on August, 14th, 2003. In this paper, the different systems for energy provision being important for the comparative assessment of sustainability are presented first. Special attention is paid to hybrid systems, which have already been applied in developing countries, while the potential of other such possibilities is briefly discussed as well. For the assessment of sustainability in Chapter 3, an indicator system on the three dimensions of sustainability ecology, socio-economic and economic issues - is developed. The different options for rural electrification are then investigated and compared with regard to these indicators. Chapter 4 then describes experiences with projects in Indonesia and Inner Mongolia, where hybrid systems were applied, while chapter 5 then outlines the key success factors for the application of hybrid systems. Finally, chapter 6 gives a summary and an outlook to the perspective of hybrid systems in developing countries. Several factors have been limiting to this work. Firstly, site visits could not be held and, therefore, the information here is limited to the findings of the literature review and the interviews.

1 Introduction

Moreover, the analysis of hybrid systems in developing countries in general can come only to rather vague results. What proves to be right in one country can be completely wrong for another country. Therefore, the findings of this analysis are always to be seen as strongly generalised and their applicability must be proven anew in each case.

2 Technologies for Rural Energy Supply

Technologies for Rural Energy Supply

This chapter gives an overview on potential solutions for rural energy supply; the options of importance for this work are discussed more in detail. The objective is to provide a technical background for the evaluation of these options in the following chapters. Generally, power supply in developing countries for rural areas takes place in three different ways (Kleinkauf, W.; Raptis, F., 1996/1997): 1. locally, by supplying single consumers and load groups; 2. decentrally, by erecting or extending stand-alone regional mini-grids; 3. centrally, by expansion of interconnected grids. The approaches of local and decentralised electrification are obviously closely connected and can be met by similar technologies. Those of importance for this paper are described more detailed firstly in the following. In a next step, the different hybrid systems, which are in operation in developing countries nowadays, will be presented, including technical aspects to be considered and main applications. Moreover, potential other hybrid solutions will be discussed against the background of applying them in developing countries. Finally, this chapter will also briefly discuss the centralised approach of the extension of the conventional grid to rural areas.

2.1

Decentralised Electrification

In highly fragmented areas or at certain distances from the grid, the decentralised approaches of regional mini-grid systems or local supply of single consumers can become competitive due to lower investments and maintenance costs compared to large scale electrification by expanding interconnected grids. Different technological options are in practice, most commonly diesel generating sets and renewable energies. 2.1.1 Diesel Generating Sets Small diesel-power generating sets (diesel gensets) have been the traditional way to address the problem of the lack of electricity. They provide a simple solution for rural electrification and can be designed for different capacities, being adapted to the needs of the consumers. In cases security of supply is not of major importance, single diesel gensets can be applied for electrification, accepting that no electricity can be supplied in times the genset is out of commission, i.e. due to repair or maintenance. This problem can be met by using a group of diesel gensets, with the other gensets providing backup (ESMAP, 2000). With diesel gensets, the electric current is produced within the village itself. The voltage of the generator is often adjusted to be higher than the required 220 Volt for the household because of high losses within the local distribution lines (Baur, J., 2000). Diesel gensets have problems with short durability, which is due to the fact that they work very inefficiently when running just at fractions of their rated capacity. Typically, the effi-

2 Technologies for Rural Energy Supply

ciency of operation is between 25-35% (Turcotte, D.; Sheriff, F.; Pneumaticos, S., 2001). Moreover, frequent start-up and shut-down procedures decrease their lifetime as well. Diesel gensets are typically just operated for around 4 hours in the evenings, and very often old motors from cars are used for the purpose of electrification. One of the basic problems for the application of diesel generating systems in developing countries, however, is more a problem related to infrastructure. Many, especially rural, areas are far away or isolated (i.e. islands) from higher developed regions so that the regular supply with diesel fuel becomes a logistical problem and an important financial burden even in countries, where fuel is heavily subsidised. Moreover, the transportation of diesel fuel can result in severe environmental damage, as experienced for example at the Galapagos Islands. In 2001, the tanker Jessica ran aground close to San Cristobal, spilling out 145,000 gallons of industrial fuel and diesel and putting the sensitive ecosystems of the islands to high risks. 2.1.2 Renewable Energy Technologies The use of renewable energy technologies is a very promising approach towards meeting environmental, social as well as economic goals associated with rural electrification. On a local level, two technologies are of high importance: Solar Home Systems (SHS) for supply of single consumers, and biogas for local mini-grids or single consumers.1 Both are presented in the following. Solar Home Systems Solar Home Systems (SHS) typically include a 20- to 100-Wp photovoltaic array and a leadacid battery with charge controller supplying energy for individual household appliances (Cabraal, A.; Cosgrove-Davies, M. Schaeffer, L., 1996). A common 50 Wp can supply lighting and a TV/radio for several hours per day (Preiser, K., 2001); the capacity can technically be expanded easily and, thus, be adapted to individual needs. The photovoltaic modules are usually installed on rooftops, they convert the insolation into electric current, which is used for loading the battery. The battery supplies electricity to the consumer during evening hours and in case of insolation shortages due to unfavourable weather conditions. Moreover, the battery offers the possibility to meet peak load demand for short periods of time. The electricity current is provided in direct current (DC). The application of inverters to provide alternating current (AC) at a voltage of 220 Volt is possible, but increases overall system costs. The systems work at voltages of 12 or 24 Volt, which requires high cross-sectional wiring in order to avoid high losses (Baur, J., 2000). Biogas Biogas systems utilise micro-organisms for the conversion of biomass (i.e. excrements from animal husbandry) for the production of biogas under anaerobic conditions2. The originating gas consists of 55 to 70% from Methane (CH4), which can be used in gas burners or motors

More potential renewable technologies include stand-alone wind turbines, wind farms, hydropower and larger-scale photovoltaics. 2 Anaerobic conditions: in absence of oxygen.

2 Technologies for Rural Energy Supply

for the production of electric current3 (Kaltschmitt, M., 2000) or for gas cookers/stoves, biogas lamps, radiant heaters, incubators and refrigerators working on biogas (GTZ, 1999a). Main component of a biogas plant is the digestion tank (fermenter), where the organic substrate is decomposed in the three steps hydrolysis, acidification and methane formation. Biogas systems are widely used in India and China for the supply of single consumers or local mini-grids.

2.2

Hybrid System Technology

Hybrid systems are another approach towards decentralised electrification, basically by combining the technologies presented above. They can be designed as stand-alone mini-grids or in smaller scale as household systems. This section wants to discuss available technology options, the system components, general technical aspects and potential applications. 2.2.1 Relevance One of the main problems of solar as well as wind energy is the fluctuation of energy supply, resulting in intermittent delivery of power and causing problems if supply continuity is required. This can be avoided by the use of hybrid systems. A hybrid system can be defined as a combination of different, but complementary energy supply systems at the same place, i.e. solar cells and wind power plants (Weber, R., 1995). A system using complementary energy supply technologies has the advantage of being able to supply energy even at times when one part of the hybrid system is unavailable. So far, three different types of hybrid systems have been applied in developing countries, including Photovoltaic Generator and Diesel Generating Set (Diesel Genset), Wind Generator and Diesel Genset, Photovoltaic and Wind Generators.

Although other renewable energy resources than solar and wind can in principle be used in hybrid systems as well, this has so far been limited to pilot projects in industrialised countries. In developing countries these other technology options have not yet gained importance. The presentation of these other potential options is left for section 2.2.3. Hybrid systems can technically be designed for almost any purpose at any capacity. Main applications for rural electrification in developing countries include independent electric power supply for

To generate 1 kWh of electricity, 1 m3 biogas is necessary (GTZ, 1999a).

2 Technologies for Rural Energy Supply

Villages, Residential Buildings, Hospitals, Schools,

- Farmhouses, - Missions, - Hotels, - Radio Relay Transmitters,

- Irrigation systems, - Desalination Systems.4

2.2.2 Hybrid Systems in Developing Countries A common hybrid system for the application in developing countries generally consists of the following main components: 1. A primary source of energy, i.e. a renewable energy resource; 2. A secondary source of energy for supply in case of shortages, i.e. a diesel genset; 3. A storage system to guarantee a stable output during short times of shortages;5 4. A charge controller; 5. Installation material (safety boxes, cables, plugs, etc.); 6. The appliances (lighting, TV/radio, etc.). Usually, a DC/AC inverter needs to be installed additionally. All these components and the problems related to their application are further described in section 2.2.4.1. Hybrid systems are applied in areas where permanent and reliable availability of electricity supply is an important issue. Maintaining high availability with renewable energies alone usually requires big renewable energy generators, which can be avoided with hybrid systems. At favourable weather conditions, the renewable part of the system satisfies the energy demand, using the energy surplus to load the battery. The batteries act as buffers, maintaining a stable energy supply during short periods of time (Blanco, J., 2003), i.e. in cases of low sunlight or low wind. Moreover, the battery serves to meet peak demands, which might not be satisfied by the renewable system alone. A charge controller regulates the state of load of the battery, controlling the battery not to be overloaded. The complementary resource produces the required energy at times of imminent deep discharge of the battery, at the same time loading the battery. Figure 2.1 shows a principle overview of how to combine PV, wind and diesel generators in a hybrid system (Roth, W., 2003).

Personal Comment given by Mr. Georg Weingarten, Energiebau Solarstromsysteme GmbH, on June 28th, 2003, at Intersolar-Fair, Freiburg, Germany. 5 Storage systems in hybrid systems in developing countries are usually battery aggregates maintaining a stable output over a time frame of one or more days. Rotating masses can be used for shorter time frames (seconds), combustion aggregates need to be used for medium- or long-term storage. A future option might be the hydrogen fuel cell.

2 Technologies for Rural Energy Supply

Solar Generator

Charge Control

G

Wind Generator Charge Control Battery Inverter Mini-Grid / Appliances

G

Diesel Generator Charge Control

Figure 2.1 Principle Circuit of Hybrid Systems

2.2.2.1 PV/Diesel Combining Photovoltaic arrays and a diesel genset provides a rather simple solution and is feasible for regions with good solar resources. As can be seen in Figure 2.1, PV/Diesel hybrid systems require a DC/AC-inverter if appliances need alternating current, since PV modules provide direct current. Compared to the common solution for rural off-grid electrification using diesel gensets alone, the hybrid solution using photovoltaic offers great potential in saving fuel. Experiences show annual fuel savings of more than 80% compared to stand-alone mini-grids on diesel genset basis,6 depending on the regional conditions and the design of the system. A project at Montague Island even reached an 87% decrease in fuel consumption (Corkish, R.; Lowe, R.; et al, 2000). The CO2 emissions decrease correspondingly. Naturally, the observed fuel saving varies over the year. The solar generator can provide about 100% of the electricity during summertime, while in winter this figure is less. Typically, in climatic regions like Germany a PV/Diesel hybrid system is designed to provide around 50% of the electricity from photovoltaic during winter, the rest being supplied with the diesel genset.7 2.2.2.2 Wind/Diesel Wind/Diesel combinations are, in principal, built up in the same way as are PV/Diesel systems. From a perspective of financial competitiveness, they can be applied in regions where average wind speed is around 3.5 m/s already (Sauer, D.; Puls, H.; Bopp, G., 2003). If wind

Personal Comment given by Mr. Georg Weingarten, Energiebau Solarstromsysteme GmbH, on June 28th, 2003, at Intersolar-Fair, Freiburg, Germany. 7 Personal Comment given by Mr. Georg Weingarten, Energiebau Solarstromsysteme GmbH, on June 28th, 2003, at Intersolar-Fair, Freiburg, Germany.

2 Technologies for Rural Energy Supply

speed is sufficient, the wind turbine is in charge of the provision of energy. During short periods of time with low winds, the battery maintains a stable system, being replaced by the diesel generating set when low winds occur over longer periods of time. 2.2.2.3 PV/Wind and PV/Wind/Diesel In some regions the exploitation of both wind and solar resources can become favourable, i.e. at coastal or mountain areas with high degree of solar radiation. Of utmost importance is here that wind and solar energy supply complement each other so that energy provision is possible over the whole year. While for the other hybrid systems applying diesel gensets, the objective in designing the system is to maximise the exploitation of the renewable energy resource, the situation is different for PV/Wind systems. Here, accurate assessment of the resources is essential for the decision on the appropriate system design. A PV/Wind hybrid system is able to provide energy all time of the day, if weather conditions are favourable. However, breakdowns in energy supply are possible, which is not suitable for some non-household applications, i.e. hospital electrification. Thus, a PV/Wind hybrid system might ideally be supported by an additional diesel generating set for times of extremely unfavourable weather conditions. This kind of hybrid system has been implemented e.g. for a hikers inn in the Black Forest of Germany (Kaltschmitt, M.; Wiese, A., 2003). The PV/Wind/Diesel hybrid system has proven successful in Germany, being highly reliable and resulting in a further reduction of diesel compared to other hybrid systems. This is obviously due to the fact that PV/Wind/Diesel hybrid systems involve a higher share of renewable energy resources. For the application in developing countries, however, it must be doubted whether this effect of further reduction of diesel use can trade off the higher investment and operation costs. 2.2.3 Other Hybrid Systems The hybrid systems implemented in developing countries so far do not reflect the whole range of potential solutions. Generally, combining any renewable resource with others is conceivable, depending on the availability of resources. In regions, where two different resources complement each other, combinations in hybrid systems are worth discussing. 2.2.3.1 Biogas Hybrid Systems PV/Wind/Biogas ASE GmbH as the performing organisation has created an autonomous hybrid power supply systems for the purification plant of Krkwitz, situated close to the Baltic Sea in Northeastern Germany, using the renewable energy resources photovoltaic, wind and biogas for energy provision. The objective was to provide 80% of the necessary energy, being able to feed up to 30% of surplus energy under good performing conditions into the public grid. In the first stage, the system was implemented using just wind energy and photovoltaic arrays, however preparing the energy management for further expansion using biogas in a decentralised cogeneration plant. The main components of the system include a 250 kWp solar generator and a 300 kW wind turbine with 3 inverted rectifiers connected in parallel (Neuhusser, G., 1996).

2 Technologies for Rural Energy Supply

10

Information on the performance of the installed system and about the further expansion with biogas could not be obtained within the framework of this work. This is due to the fact that the participating companies have been declared insolvent since implementation and the new operator of the systems could not be identified. However, the adaptation of this hybrid system for rural electrification in developing countries seems unlikely especially from a financial perspective. Combining three different types of renewable energy systems certainly involves investment costs too high for this purpose. Wind/Biogas The concept of a Wind/Biogas system is to some degree similar to Wind/Diesel hybrid systems. Instead of the diesel genset, here engine generator sets, small gas turbines, or some kinds of fuel cells can be used to generate electricity in addition to the wind turbine. The engine is fuelled by biogas, which is produced in an anaerobic digester. If the production of biogas is at times not sufficient, conventional gases as propane can be used instead. Modelling simulations proved that the availability of wind energy is upgraded by applying biogas systems additionally (Surkow, R.; 1999). A key role can be assigned to the size of the systems gas storage tank and its operating management. Depending on the management strategy and the scenario used for the type of consumers, additional secondary energy needed from conventional fuels (propane or diesel) accounts for 7-11% of the total amount of electricity. During the research for this work it was found out that these kind of systems are currently tested in developing countries in South Asia (ITDG, 2003), more detailed information could, however, not be obtained. A reasonable statement on the applicability therefore cannot be given here. Generally it is thought that biogas plants instead of diesel gensets as backup for wind or PV systems offer an environmental benign approach towards rural electrification, so that the potential should be more closely investigated. 2.2.3.2 Hydropower Hybrid Systems Wind/Large Hydropower On a seasonal basis, the two resources wind and hydropower tend to complement each other to some extent (Iowa, 2002a). Especially in winter, when river flows are low, wind has the potential to take over electricity supply. However, during late summer, both resources might become low, and the combination of both is then disadvantageous. Moreover, while hydro generators on rivers are usually at lower levels, wind resources are better at high elevations. For constant electricity generation, another energy resource would therefore be necessary. Since the combination of wind and hydropower offers just limited advantages, it is unlikely that these resources are combined in a project in developing countries, since this opportunity does not seem economically attractive. However, for some locations the situation might be different, so that the feasibility of Wind/Large Hydropower systems needs to be assessed for each case individually. Wind/Micro-Hydro and PV/Micro-Hydro While hybrid systems with large-scale hydropower generators seem unattractive, microhydropower is more feasible. Micro-hydroelectric generators are turbines that are able to op-

2 Technologies for Rural Energy Supply

11

erate under low elevation head or low volumetric flow rate conditions, being suitable for small rivers (Iowa, 2002b). Where rivers have inconsistent flow characteristics (dry in summer, frozen in winter), a hybrid system applying wind or PV support can be attractive. A careful assessment of water resources is therefore essential. 2.2.4 Technical Aspects This section gives an overview on different technical aspects related to the application of hybrid systems in developing countries, including general technical aspects and problems of the systems components as well as technical management aspects. 2.2.4.1 General Aspects General problems occurring with the elements of hybrid systems are not only specific for hybrid systems, but also common for the use of the single elements. Problems and other general technical aspects, especially those specific to the adaptation in developing countries, are briefly summarised below. Lack of infrastructure for renewable energies One of the key disadvantages of renewable energies is the fact that they apply new and not yet widespread technologies, being mostly produced in the industrialised countries. This, and the accordingly missing infrastructure for maintenance of renewable energy technologies, makes their adaptation in developing countries a rather difficult task. A holistic approach to create this kind of infrastructure and to make the use of renewable energy technologies in developing countries sustainable is imperative for energy planners and development aid organisations. The diesel generating set The non-continuous use of diesel generating sets always results in a reduction of lifetime due to the frequent start-up and shut-down procedures, as was further outlined in section 2.1.1. In comparison to the application of diesel gensets alone, the application in hybrid systems is advantageous in this respect, since here start-up and shut-down procedures are less frequent. In comparison to other technical devices, motor generating sets have a wide range of operating hours, with figures from 1,000 80,000 hours for generators with capacities less than 30 kW (Kininger, F., 2002), strongly depending on the way of operation. Moreover, diesel generating sets are rather sensitive to climatic and geographic conditions. The decrease in efficiency is 1% for every 100 m above sea level, and another 1% for every 5.5 C above a temperature of 20 C (Wuppertal Institute, 2002). To improve the situation of diesel dependence, generators using vegetable oil for operation offer a potential solution. Vegetable oil can be made available by peanut plants, rapeseed or sunflowers, to mention but a few. These plants are often locally available and CO2 neutral. Although the production of vegetable oil requires an additional initial investment, this can be traded off with later cost reduction due to fuel savings. Instead of conventional diesel gensets, a gasification system might be applied as well. Here, producer gas is made from biomass in a fluidised bed gasifier and used to fuel internal combustion engines, gas turbines or fuel cells. This approach, however, is still matter of research and currently more applicable for industrial purposes (Iowa, 2002c).

2 Technologies for Rural Energy Supply

12

The Storage System The storage device of hybrid systems, in most cases lead-acid batteries, is a very sensitive and crucial part of the system. The optimal performance of this component highly influences not only the systems performance, resulting in the need for suitable operation and management system; it also influences the overall performance costs of the system. The more optimal the performance of the battery bank, the longer the batterys lifetime, resulting in lower overall costs. The performance of a battery bank is controlled with the help of a charge controller, which guarantees that the battery is neither over-charged nor discharged too deeply. The use of storage systems in hybrid power plants has a twofold effect: on the one hand, the storage of power is meant to bypass short times of power shortages. On the other hand, the battery offers support in times of peak demands, which cannot be met by the renewable energy source alone. The following major aspects need to be considered when designing a battery bank for hybrid systems: Capacity Design: When designing a battery bank installation, it is important to note that a batterys capacity decreases over lifetime. The end of life of a battery is reached when capacity has declined to 80% of the nominal value, where the nominal value is given by the manufacturer. Thus, a battery installation should be designed based on the 80% of the nominal battery capacity (IEA, 1999a). Effect of temperature: The nominal capacity is usually given at a battery temperature of 20C. Low temperatures slow down the chemical reactions inside the battery, thus significantly reducing the utilisable capacity. High temperatures result in an increase of corrosion velocity of the batterys electrodes, thus reducing the batterys lifetime significantly. Therefore, both high and low temperatures should be avoided as far as possible (IEA, 1999a). Deep discharge to less than 50% of the capacity, overcharge and a low electrolyte level should be avoided. In order to guarantee this, the application of a charge controller is essential. Furthermore, daily control both of battery acid level and voltage are fundamental, too.8

The Charge Controller The charge controller in renewable energy systems has two fundamental functions (IEA, 1998): 1. Regulation of the current from the renewable energy generator in order to protect the battery from being overcharged. 2. Most controllers additionally regulate the current to the load in order to protect the battery from discharge. The charge controller, though being one of the least costly components in renewable energy systems, is of high importance for the systems reliability and highly influences the systems maintenance costs (IEA, 1998). This is due to the fact that an accurately working charge controller increases performance and lifetime of the battery bank.

Personal Comment given by Mr. Georg Weingarten, Energiebau Solarstromsysteme GmbH, on June 28th, 2003, at Intersolar-Fair, Freiburg, Germany.

2 Technologies for Rural Energy Supply

13

For hybrid systems, one needs to distinguish two different scenarios: firstly, in hybrid systems relying on renewable energy technologies for power supply alone (i.e. PV/Wind hybrid systems), the control of charge and discharge basically works as it does in systems with just one renewable energy resource. There, the main objective of applying charge control is to maximise the batterys lifetime. The situation, however, is different for hybrid systems using diesel gensets as a backup. Since the genset is switched on in times the renewable energy resource cannot meet the demand, the objective of system control, in addition to the former, is also to minimise costs for diesel fuel and maintenance (IEA, 1998). For the aspect of charge control, there are four major differences for diesel genset supported hybrid systems compared to simple systems with renewable energy technologies alone (IEA, 1998): 1. Battery banks in hybrid systems are generally relatively smaller and cycled more than, i.e., in pure photovoltaic systems. This increases the importance of regular equalisation and makes the cycle life the main factor determining the battery lifetime. A typical cycle life of hybrid systems battery banks consists of 2,000 3,000 cycles. 9 2. The fact that power is available on demand in diesel genset supported hybrid systems eliminates many of the vagaries associated with the fluctuating nature of renewable energy resources, making the charge control simpler. 3. Since hybrid systems are typically designed for higher loads than pure renewable systems, charge controllers are relatively less costly for the overall system. This gives potential for more costly controllers with higher functionality, without increasing the overall costs significantly. 4. Especially if the diesel genset is oversized, charge currents can be rather high. Concerning the diesel genset itself, the charge controller is giving the dispatch strategy, deciding when to turn it on, the loading at which to operate, and when to switch the genset off. This dispatch strategy is commonly quite simple: it can be determined by a low voltage point of the battery and a voltage point at which the battery is fully charged. During this time, the diesel genset runs at full loading, using the power which is not required by the load to charge the battery bank (IEA, 1998). Other dispatch strategies are to turn on the genset only when the load is reasonably large and to run it at a loading to supply just enough power in order to keep the batteries from being discharged; or to start the genset when the net load, meaning the load current minus the current available from the renewable energy generators, exceeds a certain threshold; sometimes it is even left to the user to switch on the genset (IEA, 1998). Main problems related to batteries and the charge controller in hybrid systems include temperature control, which is often difficult; many charge controllers cannot be properly adjusted; and not only that battery specifications are not always available, batteries are also usually the first component suffering from abuse (Turcotte, D.; Sheriff, F.; Pneumaticos, S., 2001).

Personal Comment given by Mr. Georg Weingarten, Energiebau Solarstromsysteme GmbH, on June 28th, 2003, at Intersolar-Fair, Freiburg, Germany.

2 Technologies for Rural Energy Supply

14

Inverters In cases where the power supplied by the renewable energy generator is given in DC, a DC/AC-inverter needs to be installed additionally. This is due to the fact that most appliances needing AC current are less costly than those requiring DC current. There are different inverter models available, which are not to be discussed within this work. All of these models, however, need to meet the following requirements (Kaltschmitt, M., 2001/2002): optimal adjustment to the renewable energy generator proper energetic inversion to DC current compliance with the principles of netparallel operation

Inverters for hybrid systems are nowadays still considered as problematic and are in need for further development (Turcotte, D.; Sheriff, F.; Pneumaticos, S., 2001). Common problems related to their application in hybrid systems include faults during transition and difficulties in starting the generators. Moreover, available models often loose their parameters when being reset, and some faults additionally require manual reset (Turcotte, D.; Sheriff, F.; Pneumaticos, S., 2001). Modern inverter technologies available on the market not only provide the normal functions of an inverter, but additionally integrate the charge control. These appliances allow with their integrated system management an automatic control of the energy sources, the charging state of the battery and the power demand of the loads. 2.2.4.2 Energy Management Systems Energy Management Systems (EMS) are a modern possibility to improve supply security of hybrid or other systems applying renewable energy resources. It serves the function of the charge controller in a more flexible way, while at the same time serving additional functions. An EMS anticipates expected loads and prioritises them, co-ordinates the application of the different generators and optimises the exploitation of the renewable energy resource, and decreases the maintenance requirements by optimising the operation of the batteries (Benz, J., 2003).

2.3

Grid-based Electrification

Finally, the centralised approach of extending the conventional grid to rural areas is the last option to be described here. Grid-based electricity is delivered to consumers at three different levels (Baur, J., 2000): 1. The electric current produced in conventional central power plants is transported via high-voltage transmission lines at a voltage of 60 200 kilovolt over long distances; 2. On a regional level, the electric current is distributed to the villages via mean-voltage grid, normally at a voltage of 10 - 22 kilovolt. 3. Inside the village, the electric current is transformed to the voltage level of 110 220/230 volt of the households.

2 Technologies for Rural Energy Supply

15

Compared to European standards, the conventional grid in developing countries lacks redundancy. This leads to lower costs on the one hand, but to less reliability on the other hand as well. Grid-based electrification is often highly favoured by rural population despite the problems with reliable electricity supply. However, the extension of the conventional grid is often not feasible from an economic point of view. Factors to be considered include10 distance of the village from the grid, number of households to be connected to the grid within the village, and household density in the villages, meaning the distances between the different houses.

Moreover, the fact that many developing countries are heavily dependent on fossil fuels makes grid-based rural electrification unattractive not only from an economic, but also from an environmental perspective.

10

For further reading see: (Cabraal, A.; Cosgrove-Davies, M.; Schaeffer, L., 1996) and (Baur, J., 2000).

3 Analysis of Impacts

16

Analysis of Impacts

Although several projects with hybrid systems for rural electrification have been carried out already, surveys investigating these systems are so far very limited. In fact, no socioeconomic survey discussing the adaptation of hybrid systems in developing countries has been conducted to date. This problem led to the idea of discussing the application of hybrid systems in developing countries not in absolute terms, but rather to compare their sustainability relative to other likely scenarios of rural electrification, which will be defined in the following section. This chapter, thus, aims to analyse the impacts of rural electrification in developing countries with hybrid systems relative to the different technology options presented above. In doing so, it is tried to find out to which degree hybrid system likely provide a sustainable option for rural electrification. The assessment of hybrid systems compared to the different other scenarios is accomplished with a set of indicators, which is developed in 3.2 and 3.3, making possible a comparison on the three dimensions of sustainability: ecological, socio-economic and economic issues.

3.1

Scope of the Analysis

For the assessment, the fictitious case of electrification of a remote village in a rural area in a developing country is discussed. It is assumed that this village is electrified with different scenarios of rural electrification, and their impacts on the three dimensions of sustainability are analysed relative to each other. Table 3.1 gives and overview on the chosen scenarios. Table 3.1 Scenarios and Technologies for Rural Electrification

No. Scenario Technologies PV-Diesel 1 Decentralised Rural Electrification with Hybrid Systems Wind-Diesel PV-Wind 2 3 4 Decentralised Rural Electrification with Diesel Gensets Decentralised Rural Electrification with Renewable Energies Centralised Rural Electrification by Grid Extension Diesel Gensets SHS Biogas Country dependent

3.1.1 Scenario Definitions This section outlines the underlying assumptions for the different scenarios for rural electrification, as they will be used for the assessment in the following. Scenario 1: Hybrid Systems The analysis of the different hybrid systems is here restricted to those which have been applied already in developing countries, namely the combinations PV/Diesel, Wind/Diesel and PV/Wind. The reason to leave out potential other technologies, as they were presented in

3 Analysis of Impacts

17

chapter 2.2.3, is that this kind of assessment would be based on too many assumptions and therefore be too speculative. The hybrid systems discussed here are designed for 24-hours electrification of a remote rural village. Where appropriate, the relevant combinations of hybrid systems are discussed as a whole; if necessary, they are discussed each for themselves. For the assessment of hybrid systems, it is here often referred to experiences of two projects on rural electrification with hybrid systems, which more detailed information could be obtained for. These projects took place in Inner Mongolia and Indonesia, and will be presented as examples in detail in chapter 4. Scenario 2: Diesel Gensets The comparison of hybrid systems with diesel gensets is based on the assumption that the considered rural village is for this scenario supplied by a diesel-based mini-grid, operated by a private operator and being implemented privately, not under the guidance of development cooperation organisations. Scenario 3: Renewable Energies For electrification of rural villages with renewable energies, two typical options are investigated here in comparison to hybrid systems: SHS and biogas systems. SHS are accounted here because they are applied widely nowadays. Since SHS are not used for productive purposes, but usually for household electrification only, this is accounted for here. It is assumed that the households of the considered village are electrified each with a SHS, accepting that the comparison with a hybrid village system is to some extent not accurate. However, it is thought that the comparison with SHS will be supportive to identify the circumstances under which the application of hybrid systems is reasonable with regard to sustainability. Biogas systems are investigated as village systems for electrification of the considered remote village, meaning that a generator is applied for producing electricity. Scenario 4: Grid Extension The extension of the conventional grid to remote rural areas is in most cases unlikely due to usually large distances of rural villages to the grid and the corresponding considerable investment necessary for the extension. However, for the assessment of hybrid systems it is seen as important to include grid extension as well in order to accurately determine the quality of hybrid system electrification. The different scenarios are all discussed as real application scenarios, which means that ideal conditions are not assumed. However, it is supposed that natural and other conditions for the realisation of the considered technical alternatives are given. It is obvious that in practical cases, only a more limited number of the technical options will be available. The scenario Rural area without electrification is not included in the analysis, since it is seen as inappropriate for being discussed here. This is due to two reasons: on the one hand, the electrification of non-electrified areas has been regarded as essential to economic and social development during the Earth Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg, 2002; on the other hand, the comparison of non-electrified areas with the electrification by different technologies seems to be inadequate in technical terms anyway. It is rather a debate on principles but a question of analytical discussion.

3 Analysis of Impacts

18

Parts of the ecological and economic analysis in the following could not be performed in general terms and required an accurate modelling of the considered remote village and the installed hybrid systems. The main assumptions are presented in the following, the details of the calculations can be found in Annex A. 3.1.2 Modelling Assumptions For the assessment of parts of the ecological and economic dimension, Trapani/Italy was chosen as an example with moderately suited weather conditions.11 Although this location is not situated in a developing country, the comparison with weather data from several other locations revealed that this location makes a generalised statement possible by offering average conditions. For the design of the hybrid systems to electrify a village in Trapani, the annual peak demand of the village was determined according to different possible village sizes. The annual consumption results from a calculated specific consumption per household and an additional 40% excess consumption for productive purposes. The hybrid systems are then designed accordingly to meet this demand with the ratio 4:1 in the cases of PV/Diesel and Wind/Diesel systems, and 1:2 in the case of PV/Wind systems. The assessment of ecological issues is performed for a village with 170 households with a calculated annual peak electricity consumption of 48,126 kWh/a. This electricity demand is then met with the different scenarios for rural electrification in order to comparatively assess hybrid systems. The calculation of investment and electricity generating costs for the assessment of economic sustainability is then performed for different village sizes for the same location.

3.2

The Concept of Indicators of Sustainability

Measuring the degree of sustainability obviously is a difficult task, leaving much space for discussion and interpretation. A system trying to describe and to quantify the degree of sustainability is the concept of indicators for sustainable development. Indicators are used to give a comprehensive view on sustainability, summarising complex information and, thus, creating a transparent and simplified system to provide information on the degree of sustainability both to decision-makers and the interested public. Most commonly, indicator sets have been developed and used to provide information on the state of sustainability of production processes or societies as a whole. Especially, the latter concept of indicators for societies as a whole has gained importance by understanding the global dimension of sustainability. A number of indicator sets have been developed, of which some of the most known on an international level have been set up by the Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). For the task of evaluating the sustainability of different energy technology concepts, no approved indicator system has been developed yet. The need for such an indicator system, how-

11

Global radiation: 1,664 kWh/m2/a; Source: Meteosat.

3 Analysis of Impacts

19

ever, is apparent and has been highlighted in a number of studies already. 12 On the one hand, it allows a relative comparison of different technologies, evaluating their current state of sustainability relative to each other, and also offering a comprehensive view on the their weak points from a perspective of sustainability. On the other hand, the results being obtained by such an indicator set can provide a data base for the evaluation of the sustainability of a society as a whole.

3.3

Developing an Indicator Set for Energy Technologies

Available indicator sets for measuring the sustainability of energy technologies have been found to be inappropriate within the framework of this work since they are commonly adapted to the conditions of industrialised rather than to those in developing countries and they include too many indicators. They do, however, provide the basis for the indicator set being developed within this work. In a first step, the three dimensions of sustainability ecological, socio-economic and economic issues needed to be broken down to a set of criteria describing these issues. In a next step, a set of indicators measuring these criteria was developed, with the indicators weighted relative to their importance for the respective dimension according to the authors opinion. This led to the following set of indicators: Table 3.2 Criteria and Indicators for the Assessment of Energy Technologies

Dimension Criteria Climate Protection Ecology Resource Protection Noise Reduction Indicator Greenhouse Gas Emissions per kWh Emissions of Air Pollutants per kWh Consumption of Unlasting Resources Noise Pollution Cultural Compatibility and Acceptance SocioEconomic Issues Overall SocioEconomic Matters Degree of Supply Equity Potential for Participation and Empowerment Potential for Economic Development Individual SocioEconomic Interests Low Costs and Tariffs Economic Issues Maintenance Economic Independence Future Potential Employment Effects Impacts on Health Investment Costs per W Electricity Generating Costs per kWh Maintenance Requirements Degree of Import Dependence and Regional Self-Supply Supply Security Degree of know-how Improvement Weighting 0.3 0.3 0.3 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.4 0.2 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.25 0.1 0.1 0.05

12

Compare for example: (Amann, D., 2003) or (Nill, M.; Marheineke, T.; Krewitt, W.; Friedrich, R.; Vo, A., 2000).

3 Analysis of Impacts

20

The discussion of the relevance of the different indicators to the three dimensions of sustainability is left to the sections below, where each indicator is presented and analysed for different energy technology options. This set of indicators tries to give a holistic picture, aiming to analyse the three dimensions of sustainability as comprehensive as possible. The constricted number of indicators allows to give significant statements on the chosen criteria by being investigated intensively. The weighting of the indicators is explained as follows: For the ecological dimension, emphasis is given to climate and resource protection due to their high importance for environmental sustainability. For the socio-economic dimension, the indicators for economic development and employment effects are emphasised in the weighting due to the fact that economic development is one of the major objectives of rural electrification. The extent to which technologies meet this objective should be weighted accordingly. For the economic dimension, the criteria of low costs and tariffs as well as maintenance are seen as most important criteria because of their high influence on the success of electrification projects. Among these criteria, the indicator of electricity generating costs is seen as being of highest importance because these costs are to be covered by the customers directly; investment costs, meanwhile, can be covered by other means, for example donor organisations. Maintenance, moreover, is of key importance for the reliable performance of the electricity supply system and, thus, weighted high as well.

In order to come to a conclusion on the performance of hybrid systems on the three dimensions of sustainability, the indicators are then summarised for each dimension individually according to their respective weight for the dimension. The discussion of sustainability in this chapter does not account for benefits or problems related to electrification in general. As an example, gender issues are not taken into account although this issue might be important in individual cases, and the assessment of these kinds of general benefits of rural electrification has been matter of a lot of research work during the last years.13 However, a detailed determination of differences can only be discussed on concrete case studies, while this work needs to stay on a more generalised level. The comparative assessment of hybrid systems with the other scenarios of rural electrification with regard to the different indicators is done with the following assessment scheme: Table 3.3 Performance Assessment Scheme

2 Comparatively very good performance 1 0 -1 Comparatively poor performance -2 Comparatively very poor performance Average performComparatively good ance or no statement performance possible

13

As examples: (Barkat, A. et al., 2002) and (Barnes, D.; DomDom, A., 2002).

3 Analysis of Impacts

21

It must be emphasised at this point that this assessment scheme only gives information on the relative sustainability of the different scenarios compared to each other. Conclusions on an absolute degree of sustainability cannot be drawn from this.

3.4

Analysis of Sustainability

This section analyses hybrid systems on the three dimensions of sustainability with the help of the indicators set up above, and compares them relative to the other options for rural electrification. For a better reading, this section presents only the assessment for hybrid systems in detail. For the relative comparison with the other scenarios, only the results are presented here. Annex C, then, gives chapter for a justification of the results. 3.4.1 Ecological Dimension 3.4.1.1 Climate Protection The degree of climate sustainability is here determined with two different indicators, Greenhouse Gas Emissions per kWh, and Emissions of Air Pollutants per kWh.

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are here measured in CO2-Equivalents per kWh. CO2Equivalents aggregate the different greenhouse gas emissions as CO2, CH4 or N2O14 due to their contribution to the greenhouse effect over a time frame of 100 years. All of these gases are emitted as products of combustion processes. The emission of air pollutants is here measured in SO2-Equivalents per kWh. SO2-Equivalents aggregate different air pollutants like SO2, NOx, dust or CO15 due to their acidification potential. Air pollutants are emitted in combustion processes as well, are closely linked to the occurrence of acid rain and have severe impacts on human health. All of these emissions occur not only during operation of energy supply systems, but during their whole life cycle including i.e. production, transport, operation, recycling. They can be assessed with the help of GEMIS (Global Emission Model for Integrated Systems), a free download software provided by the German ko-Institut.16 The results of this analysis, however, shall be shown as a relative comparison rather than as in absolute figures, since it is not a detailed life cycle assessment. For the modelling in GEMIS, this electricity demand was met with the different technology scenarios. For the extension of the conventional grid, three country examples (Brazil, China, and South Africa) are chosen as representatives. The details of the modelling assumptions and a detailed discussion of the results can be found in Annex B, the main results are presented here.

14 15

CO2 = carbon dioxide; CH4 = methane; N2O = nitrous oxide (laughing gas). SO2 = sulphur oxide; NOx = nitrogen oxide; CO = carbon monoxide. 16 Available at: http://www.oeko.de/service/gemis/.

3 Analysis of Impacts

22

3.4.1.1.1 Greenhouse Gas Emissions per kWh Scenario Comparison Figure 3.1 shows the modelling results of GHG emissions attributable to the different scenarios for meeting the electricity demand of the chosen village. The scenario of grid extension is described with the chosen countries Brazil, South Africa and China.

60.000 Greenhouse Gases [kg CO2-Equivalents] 50.000 40.000 30.000 20.000 10.000 0 PV/ Wind/ PV/ Diesel SHS Biogas Brazil South China Diesel Diesel Wind Af rica

Figure 3.1 GEMIS Results: Greenhouse Gas Emissions The comparison of GHG emissions per kWh shows that especially PV/Wind hybrid systems are highly preferential. PV/Wind systems result in lower greenhouse gas emissions than all other scenarios except SHS, which similar greenhouse gas emissions can be attributed to. The GHG emissions resulting from diesel-based hybrid systems are higher due to the application of the diesel genset. In comparison to purely renewable energy systems, their performance is therefore worse. Compared to conventional energy systems, however, diesel-based hybrid systems are advantageous. Figure 3.2 summarises the results of the analysis of GHG emissions on the basis of the comparative assessment scheme. It shows that hybrid systems can be assessed as being supportive for the objective of decreasing GHG emissions compared to conventional energy systems. Purely renewable hybrid systems as PV/Wind are here performing even better than dieselbased systems.

3 Analysis of Impacts

23

2 1 0 PV/ Diesel -1 -2 Wind/ Diesel PV/ Wind Diesel SHS Biogas Grid Extension

Figure 3.2 Comparative Assessment of GHG Emissions

3.4.1.1.2 Emissions of Air Pollutants per kWh Scenario Comparison The comparison of emissions of air pollutants again shows a preference for the PV/Wind system. The other hybrid systems suffer in their performance mainly from the emission of NOx in the combustion process of the diesel generator.

800 Air Pollutants [kg SO2-Equivalents] 700 600 500 400 300 200 100 0 PV/ Wind/ PV/ Diesel SHS Biogas Brazil South China Diesel Diesel Wind Africa

Figure 3.3 GEMIS Results: Emissions of Air Pollutants While SHS almost do not result in any emission of air pollutants due to the absence of a combustion process, the amount of air pollutants is considerable in the case of biogas. These emissions result mainly from sulphur bound in the substrate. Diesel-based mini-grids result in the highest amount of air pollutants due to NOx emissions in the combustion process. They are therefore strongly disadvantageous in this respect. The comparison with the conventional grid clearly shows a high dependence on the respective energy sources used in such grids. While Brazil applies mainly hydroelectric power and therefore hardly has significant emissions of air pollutants, China and South Africa rely mainly on coal with the associated high SO2-emissions from sulphur bound in the coal. Thus, the application of diesel-based hybrid systems is associated with more emissions of air pollutants compared to the grid of Brazil, while they emit less air pollutants compared to the grids of China and South Africa. PV/Wind systems are advantageous in any case.

3 Analysis of Impacts

24

For the comparative assessment, PV/Wind systems and SHS are evaluated to perform comparatively best. A comparatively good performance can be attributed to PV/Diesel, Wind/Diesel and biogas systems. The conventional grid is concluded to perform worst with regard to the emission of air pollutants, because most developing countries apply a significant share of fossil resources for electricity generation.

2 1 0 PV/ Diesel -1 -2 Wind/ Diesel PV/ Wind Diesel SHS Biogas Grid Extension

Figure 3.4 Comparative Assessment of Air Pollutants Emissions