Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sales Force Integration

Uploaded by

annvf78Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sales Force Integration

Uploaded by

annvf78Copyright:

Available Formats

1

OCTOBER 2009

o r g a n i z a t i o n

p r a c t i c e

Mastering sales force integration in a merger

Companies can seize the opportunity in mergers by involving employees and customers in the integration process, retaining critical staff, generating momentum by quickly winning key accounts, and serving the right customers in the right way.

Ajay Gupta, Tom Stephenson, and Andy West

Make no mistake: mergers are challenging. Even so, they can provide organizations with transformative possibilities. One of the biggestthe integration of sales forcesis central to ensuring revenue growth and driving the value that mergers promise but often fail to realize.

Yet integrating sales forces ranks among the hardest parts of a merger to executea fact not lost on senior executives (exhibit). Mergers generate anxiety inside and outside the companies involved, and competitors happily exploit such fears to woo star salespeople and poach customers. Nonetheless, savvy companies embrace the opportunity to build a new sales organization that is more than the sum of its parts. We have identified four steps essential to facilitating the successful integration of sales operations. At the top of the list: understanding the importance of sharing information about the integration process with customers and the sales force. Many companies take the opposite approach and are surprised when postmerger revenue fails to meet expectations. In addition, the combined sales team must quickly win prominent accounts to build momentum and generate internal confidence in the merger. The executives running the integration effort must also recognize that, as important as sales reps are, essential support people must be identified and retained. Finally, senior managers should review the merged portfolio of customers and make tough calls about those that are worth new investments and those that might be shed or given less attention. Web 2009

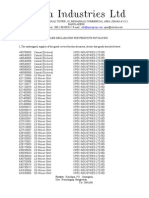

Sales merger Overall, we Exhibit 1 of 1find that with careful planning and implementation, acquiring companies can revitalize not only their own organizations but skills and relationships with Glance: Respondents put a high priority on improving thealso theircapabilities required to customers (see sidebar, A case study of rapid sales integrate sales operations after a merger. force integration). Exhibit title: Need for improvement Exhibit

Need for improvement

In which functional area do you see the biggest need for improvement in regard to integration skills/capabilities, given the focus of your future merger activity?

% of respondents (n = 89)

Sales/marketing HR IT Operations/supply chain Finance R&D Other 4 7 8 18 16 20

27

Source: 2009 McKinsey survey of experienced M&A professionals

Overcommunicate

Some companies try to shield their customers from messy merger-related activities such as changes in organizational structures and roles, customer-engagement rules, and customer support. But our experience suggests that most customers are willing and even excited to help a merging organization reshape itself: they prefer to be involved withrather than to be told, after the factwhat changes are being made. Mergers therefore give companies a chance to improve relationships with customers and to address their unfulfilled needs. Many organizations are loath to assume new commitments during a time of transitionthey believe that management has enough issues to resolve without involving customers in the merger process. Yet such discussions are critical in determining what a merger can and cant achieve and the role customers can play in shaping that outcome. Leading companies therefore take an expansive view of their relationships with customers, discussing not only the details of the sales relationshipthe nuts and bolts of whats sold and bought, and at what pricesbut also issues such as contracting, delivery, support, and even how often executives from both sides meet. Communicating openly and involving customers makes them feel that their needs and expectations are being addressed and turns them into a party to a mergers success. Consider what happened at a networking-equipment company that found that its customers were worried about its postmerger product road mapthe schedule specifying product ranges, prices, release dates, and other such details. Competitors fed this anxiety by questioning which products the merged company would support after the integration, implying that there was too much uncertainly to do business with it. In response, the company quickly developed an integrated product road map before the merger even closed, so it could work with customers and launch a campaign to publicize its revamped product lineup as soon as the deal was completed. That experience conveys another valuable lesson: involve salespeople in the integration process. Because most of them need to maintain a laser-like focus on revenue targets and compensation in order to succeed, many companies seek to protect them at this point so they can concentrate on customers and continue to make sales. The problem is that customers and salespeople react to ambiguity. Uncertainty about the organizations structure, customer-engagement rules, product road map, or operational details can all slow revenue generation as customers spend time discussing the issues and planning for the worst. Without firm direction, salespeople trying to quiet these concerns may give answers that are ultimately inconsistent with the developing integration plan, so that the reps seem out of the loop or the organization looks unresponsive or plain incompetent. Sales reps also need reassurance about internal issues, such as how they will be compensated and who will cover which accounts. Otherwise, in the worst-case scenario, high performers may defect to competitors.

In short, ambiguitynot the distraction of integration itselfis the fundamental enemy. Best-practice acquirers define, as specifically as possible, how the merged organization will eventually look and the pace and timing of integration. They also carefully track progress. Managers cant know all the answers, but they should describe their intentions and the criteria for decisions and commit themselves to answering the fields questions according to a specific pace and timing. The sales integration process should be clearly tracked and closely monitored: that means following not only lagging indicators, such as revenue, but also leading indicators, such as the volume of training activity on new products, how long deals take to close, how often prices or contracts must be altered, sales attrition, and winlose rates for customers previously serviced by both merging companies.

Build sales momentum

Best-practice integrators know that the first hundred days after a merger closes are critical to demonstrating its value and tangible benefits to the sales force, customers, and investors. These companies focus on winning a few critical large transactions early as proof of concept cases, using the full weight of the top team, product development, salespeople, and technical support. Sales of products identified as quick winsthose most easily sold to customers of both merging companies initiallyprovide an immediate, focused experience for the sales force. At the outset, sales performance incentives should be aimed at such transactions. In the case of a semiconductor merger, for example, much of the deals value reflected the possibility of integrating products into a combined chip set. Because the merging companies persuaded a few key customers to commit themselves to this vision quickly, sales reps were reassured that the deal was sound and would help them succeed both in sales volumes and compensation. The early sales in turn spurred enthusiasm and generated revenue momentum among other customers as well. One barrier to achieving this kind of early sales success is the time needed to bring together the merging companies back-office systems and processesparticularly IT and financea problem that can hamper the execution of orders. In our experience, the excitement around a typical deal lasts six to nine months, not enough time for operations and IT to deliver a strong, integrated foundation for sales systems and processes. The challenge of such longterm planning can put a deals early sales momentum at risk. Leading integrators must accept the reality that momentum and a seamless transition may require temporary plug-and-play solutions for IT and finance. These work-arounds ensure that the sales reps can make forecasts, enter joint orders, gain pricing approval, manage exceptions and orders that need to be expedited, and troubleshoot issues in sales crediting and compensation. Over the long term, there will be time to cherry-pick each companys strongest processes, methodologies, and tools.

Look beyond sales reps

There is little argument that retaining the top talent of a sales force is critical, and its easy to use pure revenue statistics to decide who stays and who goes in any integration effort. Yet all

A case study of rapid sales force integration

Following a merger, many executives must decide how fast to integrate sales forces. Moving too quickly invites a clash of corporate cultures, sagging morale, and lost sales momentum. Moving too slowly leaves employees and customers in limbo, with competitors only too willing to poach accounts and top salespeople. The president of one leading medical-device company decided that sooner was better than later: he set an ambitious goal of presenting a single face to customers no more than eight weeks after closing a merger with a rival. Within two months of the deals close, senior management had to decide the fate of more than 300 sales reps and of accounts totaling several hundred million dollars. The aggressive timeline called for careful, systematic, and rigorous planning. Immediately after the merger was announced, the leadership of the two companies sales operations went to work. Both sales forces had a record of solid performance and a strong culture, yet differences were already apparent. One company had a highly entrepreneurial ethos: frontline sales reps had more leeway and authority to get deals done and celebrated great performance more exuberantly. The other company was more low key and measured: roles were better defined, corporate oversight was greater, and employees regarded their merger partners as a bit brash. The companies had different approaches to staff compensation and performance reviews, so directly comparing the sales records of reps was impossible. Yet common ground emerged. Over the course of several meetings among sales leaders from both companies after the deals announcement, the business objectives and goals of a larger and more powerful combined sales force were hashed out. The leaders reached agreement on a new selling modelfor instance, the larger combined sales force would make it possible to focus more intensely on physicians in offices, in addition to the traditional focus on hospitals. A technology that monitors audience responses in real time was used during these sessions between the two sales leadership teams. This helped each side to understand the others culture, an understanding that played a critical role in enabling the leaders to determine how the two teams should be united. These cultural-awareness sessions also helped the leaders to work with reps and managers from both companies and to retain the swagger while gaining the better oversight. Special clean teams examined both companies current and projected sales data to determine how effective the merged entity could be. A new performance-ranking system made it possible to compare reps directly, which in turn allowed the clean teams (with leadership oversight) to create a first blueprint for integration. The blueprint included a new territory structure and organization for the sales reps, defining who would cover which region and how the new entity would ultimately serve customers in a way that minimized disruption for them and the organization. Meanwhile,

sales leaders began planning the thorny aspects of integration, such as compensation and benefits, training requirements, and the future of support functions. A day-by-day plan was developed for activities required once the merger closed. Problems the clean teams couldnt resolve were noted, so the broader combined sales teams could address them after the close. Within three weeks of the deals closing, the combined companies had already implemented integrated policies on field compensation, benefits, relocation, and separation. Two weeks thereafter, executives had established the complete integrated deployment of the combined sales forces, using the clean-team output as a starting point and refining it through workshops. Retention offers were made quickly to managers and sales reps. A national sales meeting assembled the combined organization and helped forge a new identity and culture. Accelerated training of sales reps on the expanded product portfolio began, and plans were made to transfer relationships for each account and sales rep. In the weeks after the merger closed, a war room oversaw the sales integration process, tracking sales and customer service performance, monitoring competitors, and following the attrition or competitive poaching of sales reps. This process wasnt easy. The pace of the sales integration effort meant that key personnel from both companies were doing double or even triple duty, and the risk of burnout had to be monitored constantly. While the combined organizations leaders communicated and provided one another with constant feedback, cultural differences and the sometimes bruised egos of sales reps had to be dealt with and decisions made rapidly. Customers had to be kept informed about the progress of the effort to feel they had an investment in it, and sales reps needed quick wins to feel that the merger was paying off and to maintain sales momentum. The net result of this activity was a reduction in many of the risks usually associated with integrating sales forces. Uncertainty among sales reps about the mergers impact on them declined, making overtures from competitors less appealing and ensuring that top sales talent remainedcompetitors dont try to poach also-rans. Effective communication mitigated uncertainty among customers, while the aggressive deadline provided an end date to the upheaval. Quick sales wins, coupled with an expanded product portfolio and greater coverage, proved the logic of the deal to employees and customers, minimizing the risk that it would be perceived as a mistake. The presidents deadline was met: eight weeks after the merger closed, an integrated sales force was in place, with one face to the customer, and the combined entitys revenue growth accelerated.

organizations employ certain people whose contributions are less easily measuredbut who are nevertheless the glue of a high-performing sales team. Best-practice integrators identify these people and their place in the organizations internal network and target them for retention. There may, for instance, be sales support staff with unique and specific technical expertise, in functional areas like IT and finance, for sales processing or approval. Whats more, in many start-ups and medium-sized enterprises, some people fill many roles. Organizations can map such an internal network by using a variety of techniques to ensure that the people who hold it together are retained. Otherwise, an overly rigid or out-of-touch HR process for categorizing employees risks losing the richness of these relationships. Finally, companies must consider the sequence for unveiling the integrated sales unit and selecting staff for retention. Reorganizing the frontline sales staff and back-office support simultaneously, for example, can significantly disrupt customer service. Deferring changes in support functions until account coverage and related matters have been resolved may help ensure that customers are served without interruption.

Review your customer portfolio

Most sales organizations in a merger or acquisition focus on retaining all customers, regardless of expense. Thats natural, given the heightened awareness of competitors actions and the desire to show that a company is meeting its revenue expectations. Yet mergers provide an opportunity not only to refocus on the most important and promising customers but also to allocate resources to meet their needs more fully. While altering long-standing customer relationships is never easy, best-practice integrators use the merger process to evaluate a portfolio critically. To ensure that they focus on the most profitable accounts, they examine the true costsupport activities as well as sales rep timeof serving various types of customers. They explore options to reallocate account resources, something that may mean reducing coverage for customers that receive top-tier service because of historical relationships rather than profitability. And they are willing to have difficult conversations with customers to discuss contracts, terms and conditions, pricing, and anything else that affects the profitability of accounts. Sometimes, you must be willing to shed customers. A technology company, for example, acquired a smaller firm that had been using its engineering team as a quasisales force: customers had come to expect that it would customize products for them. Once the two organizations merged, the acquirer refocused the team back on core engineering. The decision cost some sales to smaller customers, but the net effect on profitability was more than offset by increased engineering productivity.

Related articles M&A strategies in a down market The role of networks in organizational change The elusive art of postmerger leadership Managing a marketing and sales transformation Keeping your sales force after the merger

Integrating sales organizations is never easy. Yet companies can embrace the opportunity before them by involving customers and employees in the merger process, generating momentum by quickly winning key accounts, retaining critical staff, and serving the right customers in the right way. These steps, our experience shows, can ensure that the sales force helps rather than hinders a mergers overall success.

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of Sophie Birshan, Kameron Kordestani, and Sunil Rayan to this article. Ajay Gupta is a director in McKinseys Chicago office, Tom Stephenson is a principal in the Silicon Valley office, and Andy West is a principal in the Boston office. Copyright 2009 McKinsey & Company. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- An Overview of Itemized DeductionsDocument19 pagesAn Overview of Itemized DeductionsRock Rose100% (1)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- WHAT IS A BIRTH CERTIFICATE-Estate Equitable Title Receipt PDFDocument8 pagesWHAT IS A BIRTH CERTIFICATE-Estate Equitable Title Receipt PDFApril Clay75% (4)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- How To Start With Direct EquityDocument25 pagesHow To Start With Direct EquityKrishna Kishore ANo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Licensing HandbookDocument88 pagesLicensing HandbookajoiNo ratings yet

- Full Set - Investment AnalysisDocument17 pagesFull Set - Investment AnalysismaiNo ratings yet

- EPC y EPCMDocument22 pagesEPC y EPCMGuillermoAlvarez84No ratings yet

- Concerns with DCF analysis for Intermediate Chemicals Group projectDocument2 pagesConcerns with DCF analysis for Intermediate Chemicals Group projectJia LeNo ratings yet

- Luxury Housing Development in Ethiopia's CapitalDocument13 pagesLuxury Housing Development in Ethiopia's CapitalDawit Solomon67% (3)

- TACTICAL FINANCING DECISIONSDocument24 pagesTACTICAL FINANCING DECISIONSAccounting TeamNo ratings yet

- Notes ReceivableDocument15 pagesNotes ReceivableJenny LariosaNo ratings yet

- Week 5 SCEDocument4 pagesWeek 5 SCEAngelicaHermoParas100% (1)

- Special Topics in Income TaxationDocument78 pagesSpecial Topics in Income TaxationPantas DiwaNo ratings yet

- Letter PADDocument151 pagesLetter PADBogra BograaNo ratings yet

- Cash Flow statement-AFMDocument27 pagesCash Flow statement-AFMRishad kNo ratings yet

- Data Stream Global Equity ManualDocument72 pagesData Stream Global Equity Manualfariz888No ratings yet

- Overview of Mutual Fund Ind. HDFC AMCDocument67 pagesOverview of Mutual Fund Ind. HDFC AMCSonal DoshiNo ratings yet

- Anand ProjectDocument75 pagesAnand Projectsrinidhiprabhu_koteshwaraNo ratings yet

- Intermediate Accounting I IntroductionDocument6 pagesIntermediate Accounting I IntroductionJoovs JoovhoNo ratings yet

- Injection Plastics Company Has Been Operating For Three Years ADocument1 pageInjection Plastics Company Has Been Operating For Three Years AM Bilal SaleemNo ratings yet

- PseDocument3 pagesPseAsh1No ratings yet

- The Importance of Porters Five ForcesDocument2 pagesThe Importance of Porters Five ForcesDurga 94No ratings yet

- THUYET MINH NCKH 2018-2019 bản chínhDocument6 pagesTHUYET MINH NCKH 2018-2019 bản chínhLương Vân TrangNo ratings yet

- Adv 1 - 6 - Intercompany Profit Transactions - Plant Assets - Handout #1Document12 pagesAdv 1 - 6 - Intercompany Profit Transactions - Plant Assets - Handout #1ria fransiscaieNo ratings yet

- Gamboa v. Teves, 652 SCRA 690Document62 pagesGamboa v. Teves, 652 SCRA 690d-fbuser-49417072No ratings yet

- IV Sem MBA - TM - Strategic Management Model Paper 2013Document2 pagesIV Sem MBA - TM - Strategic Management Model Paper 2013vikramvsuNo ratings yet

- Jackson's Goldman LoanDocument1 pageJackson's Goldman LoanThe WrapNo ratings yet

- Uconn Foundation: Investment ManagementDocument35 pagesUconn Foundation: Investment ManagementBoqorka AmericaNo ratings yet

- To Invest in The Multibagger Parag Milk PDFDocument3 pagesTo Invest in The Multibagger Parag Milk PDFChetan PanchamiaNo ratings yet

- Allegations Against George HudginsDocument20 pagesAllegations Against George HudginsThe Daily Sentinel100% (2)

- BA7106-Accounting For Management Question Bank - Edited PDFDocument10 pagesBA7106-Accounting For Management Question Bank - Edited PDFDhivyabharathiNo ratings yet