Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Axiom of FM

Uploaded by

bamkinOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Axiom of FM

Uploaded by

bamkinCopyright:

Available Formats

MODULE 2

TEN AXIOMS THAT FORM THE BASICS OF FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT

Axiom 1: The Risk-Return Tradeoff - We Wont Take on Additional Risk Unless We Expect to Be Compensated with Additional Return

At some point we have all saved some money. Why have we done this? The answer is simple: to expand our future consumption opportunities. We are able to invest those savings and earn a return on our dollars because some people would rather forgo future consumption opportunities to consume more now. Assuming there are a lot of different people that would like to use our savings, how do we decide where to put our money?

First, investors demand a minimum return for delaying consumption that must be greater than the anticipated rate of inflation. If they didnt receive enough to compensate for anticipated inflation investors would purchase whatever goods they desired ahead of time or invest in assets that were subject to inflation and earn the rate of inflation on those assets. There isnt much incentive to postpone consumption if your savings are going to decline in terms of purchasing power.

Investment alternatives have different amounts of risk and expected returns. Investors sometimes choose to put their money in risky investments because these investment offer higher expected returns the more risk an investment has, the higher will be its expected return. This relationship between risk and expected return is shown in figure 1-1.

Notice that we keep referring to expected return than actual return. We may have expectations of what the returns from investing will be, but we cant peer into the future and see what those returns are actually going to be. If investors could see into the future no one would have invested money in the dressmaker Leslie Fay, whose stock dropped 43 percent on April 5, 1993, when it announced it was filing for bankruptcy. Until after the fact, you are never sure what the return on an investment will be. That is why General Motors bonds pay more interest

than U.S. treasury bonds of the same maturity. The additional interest convinces some investors same to take on the added risk of purchasing a General Motors bonds.

This risk-return relationship will be a key concept as we value stocks, bonds, and return proposed new projects throughout this text. We will also spend time determining how to measure risk. Interestingly, much of the work for which the 1990 Nobel Prize for Economics was awarded centered on the graph in Figure 3 and how to measure risk. Both the graph and the risk riskreturn relationship it depicts will reappear often in this text. picts

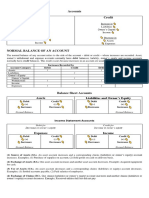

Figure 2. The Risk-Return Relationship Return

Axiom 2: The Time Value of Money A Dollar Received Today is Worth More Than a Dollar Received in the Future

A fundamental concept in finance is that money has a time value associated with it: A dollar received today is worth more than a dollar received a year from now. Because we can earn interest on money received today, it is better to receive money earlier rather than later. In your rather economics courses, this concept of the time value of money is referred to as the opportunity cost of passing up the earning potential of a peso today.

In this text we focus on the creation and measurement of wealth. To measure wealth or value we will use the concept of the time value of money to bring future benefits and costs of a project back to present. Then, if the benefits outweigh the costs the project creates wealth and should be accepted; if the costs outweigh the benefits the project does not create wealth and should be rejected. Without recognizing the existence of the time value of money, it is impossible to evaluate projects with future benefits and costs in a meaningful way.

To bring future benefits and costs of a project back to the present, we must assume a specific opportunity cost of money, or interest rate. Exactly what interest rate to use is determined by Axiom 1, The Risk Return Tradeoff, which states investors demand higher returns for taking on more projects. Thus, when we determine the present value of future benefits and costs, we take into account that investors demand a higher return for taking on added risk.

Axiom 3: Cash Not Profits Is King

In measuring wealth or value we will use cash flows, not accounting profits, as our measurement tool. Cash flows are received by the firm and can be reinvested. Accounting profits, on the other hand, are shown when they are earned rather than when the money is actually in hand. A firms cash flows and accounting profits may not occur together. For example, capital expenses, such as the purchase of new equipment or a building, are depreciated over several years, with the annual depreciation subtracted from profits. However, the cash flow associated with this expense generally occurs immediately. Therefore cash outflows involving paying money out and cash inflows that can be reinvested correctly reflect the timing for the benefits and costs. At this point, the first three axioms we have presented can be used to determine the value of any asset, be it a business, a new project, or a financial asset like a share of stock or a bond. In future chapters we will provide the techniques for determining the value of an asset based on these axioms.

Axiom 4: Incremental Cash Flows Its Only What Changes That Counts

In making business decisions, we are concerned with the results of decisions: What happens if we say yes versus what happens if we say no? Axiom 3 states that we should use

cash flows to measure the benefits that accrue from taking on a new project. We are now fine tuning our evaluation process so that we only consider incremental cash flows. The incremental cash flow is the difference between the cash flows if the project is taken on versus what they will be if the project is not taken on.

Not all cash flows are incremental. For example, when Leaf Inc., a manufacturer of sports card, introduced Donruss Triple Play Baseball Cards in 1992, the product competed directly with the companys Leaf and Dunuss Baseball cards. There is no doubt that some of the sales dollar that are ended up with Donruss triple Play Cards would have been spent on Donruss or Leaf Cards if Triple Play Cards had not been available. Although the Leaf Corporation meant to target the low-cost end of the base cards market held by tops, there was no question that Triple Play sales bit into actually cannibalized sales from the companys existing product lines. The difference between revenues generated by introducing the new cards versus maintaining the original series are the incremental cash flows. This difference reflects the true impact of the decision. What is important is that we think incrementally. Our guiding rule in deciding whether a cash flow is incremental is to look at the company with and without the new product. In fact, we will take this incremental concept beyond cash flows and look at all consequences from all decisions on an incremental basis.

Axiom 5: The Curse of Competitive Markets Why Its Hard to Find Exceptionally Profitable Projects

Our job as financial manager is to create wealth. Therefore, we will look closely at the mechanics of valuation and decision making. We will focus on estimating cash flows, determining what the investment earns and valuing assets and new projects. But it will be easy to get caught up in the mechanics of valuation and lose sight of the process of creating wealth. Why

is it so hard to find projects and investments that are exceptionally profitable? Where do profitable projects come from? The answers to these questions tell us a lot about how competitive markets operate and where to look for profitable projects.

In reality, it is much easier evaluating profitable projects than finding them. If an industry is generating large profits, new entrants are attracted. The additional competition and added capacity can result in profits being driven down to the required rate of return. Conversely, if an industry is returning profits below the required rate of return, then some participants in the market drop out, reducing capacity and competition. In turn, prices are driven back up. This is precisely what happened in the VCR video rental market in the mid-1980s. this market developed suddenly with the opportunity for extremely large profits. Because there were no barriers to entry, the market quickly was flooded with new entries. By 1987 the competition and price cutting produced losses for many firms moving out of the video rental industry, profits again rose to the point where the required rate of return could be earned on invested capital.

In competitive markets, extremely large profits simply cannot exist for very long. Given that somewhat bleak scenario, how can we find good projects that is, projects that return more than the required rate of return? Although competition makes them difficult to find, we have to invest in markets that are not perfectly competitive. The two most common ways of making markets less competitive are to differentiate the product in some key way to achieve a cost advantage over competitors.

Product differentiation insulates a product from competition, thereby allowing prices to stay sufficiently high to support large profits. If products are differentiated, consumer choice is no longer made by price alone. For example, in the pharmaceutical industry, patents create competitive barriers. Smith Kline Beckmans Tagamet, used in the treatment of ulcers, and Hoffman-La Roches Valium, a tranquilizer, are protected from direct competition by patents.

Service and quality are also used to differentiate products. For example, Caterpillar Tractor has long prided itself on the quality of its construction and earth-moving machinery. As a result, it has been able to maintain its market share. Similarly, much of Toyota and Hondas

brand loyalty is based on quality. Service can also create product differentiation, as shown by McDonalds fast service, cleanliness and consistency of product that brings costumers back.

Whether product differentiation occurs because of advertising, patents, service, or quality, the more the product is differentiate from competing products, the less competition it will face and the greater the responsibility of large profits.

Economies of scale and the ability to produce at a cost below competition can effectively deter new entrants to the market and thereby reduce competition. The retail hardware industry is one such case. In the hardware industry there are fixed cost that are independent of the stores size. For example, inventory costs, advertising expenses, and managerial salaries are essentially the same regardless of annual sales, therefore, the more sales that can be used to full potential.

Regardless of how the cost advantage is created by economies of scale, proprietary technology, or monopolistic control of raw materials the cost advantage deters new market entrants while allowing production at below industry cost. This cost advantage has the potential of creating large profits.

The key to locating profitable investment projects is to first understand how and where they exist in competitive markets. Then the corporate philosophy must be aimed at creating or taking advantage of some imperfection in these markets, either through product differentiation or creation of a cost advantage, rather than looking to new markets or industries that appear to provide large profits. Any perfectly competitive industry that looks too good to be true wont be for long.

Axiom 6: Efficient Capital Markets The Markets are Quick and the Prices Are Right

Our goal as financial managers is the maximization of shareholder wealth. Decisions that maximize shareholder wealth lead to an increase in the market price the existing common stock. To understand this relationship, as well as how securities such as bonds and stocks are valued or

priced in the financial markets, it is necessary to have an understanding of the concept of efficient markets.

Whether a market is efficient has to do with the speed with which information is impounded into security prices. An efficient market is characterized by a large number of profitdriven individuals who act independently. In addition, new information regarding securities arrives in the market in a random manner. Given this setting, investors adjust to new information immediately and buy and sell the security until they feel the price correctly reflects the new information. Under the efficient market hypothesis, information is reflected in security prices with such speed that there are no opportunities for investors from publicly available information. Investors competing for profits ensure that security prices appropriately reflect the expected earnings and risks involved and thus the true value of the firm.

What are the implications of efficient markets for us? First, the price is right. Stock prices reflect all publicly available information regarding the value of the company. This means we can implement our goal of maximization of shareholder wealth by focusing on the effect each decision should have on the stock price if everything else were held constant. Second, earnings manipulations through accounting changes will not result in price changes. Stock splits and other changes in accounting methods that do not affect cash flows are not reflected in prices. Market prices reflect expected cash flows available to shareholders. Thus, our pre-occupation with cash flows to measure the timing of the benefits is justified.

As we will see, it is indeed reassuring that prices reflect value. It allows us to look at prices and see value reflected in them. While it may make investing a bit less exciting, it makes corporate finance much less uncertain.

Axiom 7: The Agency Problem Managers Wont Work for the Owners Unless Its in Their Best Interest

Although the goal of the firm is the maximization of shareholder wealth, in reality the agency problem may interfere with the implementation of this goal. The agency problem results

from the separation of management and the ownership of the firm. For example, a large firm may be run by professional managers who have little or no ownership in the firm. Because of this separation of the decision makers and owners, managers may make decisions that are not in line with the goal of maximization of shareholder wealth. They may approach work less energetically and attempt to benefit themselves in terms of salary and perquisites at the expense of shareholders.

The costs associated with the agency problem are difficult to measure, but occasionally we see the problems effect in the marketplace. For example, if the market feels management of a firm is damaging shareholder wealth, we might see a positive reaction in stock price to the removal of that management. In 1989, on the day following the death of John Dorrance, Jr., chairman of Campbell Soup, Campbells stock price rose about 15 percent. Some investors felt that Campbells relatively small growth in earnings might be improved with the departure of Dorrance. There was also speculation that Dorrance was the major obstacle to a possible positive reorganization.

If the management of the firm works for the owners, who are actually the shareholders, why doesnt the management get tired if they dont act in the shareholders best interest? In theory, the shareholders pick the corporate board of directors and the board of directors in turn picks the management. Unfortunately, in reality the system frequently works the other way around. Management selects the board of director nominees and then distributes the ballots. In effect, shareholders are offered a slate of nominees selected by the management. The end result is management effectively selects the directors, who then may have more allegiance to managers than to shareholders. This is turn sets up the potential for agency problems with the board of directors not monitoring managers on behalf of the shareholders as they should.

We will spend considerable time monitoring managers and trying to align their interests with shareholders. Managers can be monitored by auditing financial statements and mangers compensation packages. The interests of managers and shareholders can be aligned by establishing management stock options, bonuses and perquisites that are directly tied to how closely their decisions coincide with the interest of shareholders. This agency problem will

persist unless an incentive structure is set up that aligns the interests of managers and shareholders. In other words, whats good for shareholders must also be good for managers. If that is not the case, managers will make decisions in their best interest rather than maximizing shareholder wealth.

Axiom 8: Taxes Bias Business Decisions

Hardly any decision is made by the financial manger without considering the impact of taxes. When we introduced Axiom 4, we said that only incremental cash flows should be considered in the evaluation process. More specifically, the cash flows will consider will be after-tax incremental cash flows to the firm as whole.

When we evaluate new projects, we will see income taxes playing a significant role. When the company is analyzing the possible acquisition of a plant or equipment, the returns from the investment should be measured on an after-tax basis. Otherwise the company will not truly be evaluating the true incremental cash flows generated by the project.

The government also realizes taxes can bias business decisions and uses taxes to encourage spending in certain ways. If the government wanted to encourage spending on research and development projects it might offer an investment tax credit for such investments. This would have the effect of reducing taxes on research and development projects, which would in turn increase the after-tax cash flows from those projects. The increased cash flow would turn some otherwise unprofitable research and development projects into profitable projects. In effect, the government can use taxes as a tool to direct business investment to research and development projects, to the inner cities, and to projects that create jobs.

Taxes also play a role in determining a firms financial structure, or mix of debt and stock. Although this subject has been the focus of intense controversy for over three decades, one aspect remains constant: The tax laws give debt financing a definite cost advantage over stock. As we noted when we examined how taxes are computed, interest payments are a tax-deductible expense, whereas dividend payments to stockholders may not be used as deductions in computing

a corporations taxable profits. Interest payments lower profits, which are not a cash flow item, payments and this in turn lowers taxes due, which are a cash flow item. In effect, paying interest as opposed to dividends reduces taxes.

Axiom 9: All Risk Are Not Equal Some risk Can Be Diversified Away, and Some Cannot

Much of finance centers on Axiom 1, The Risk Return Tradeoff. But before we can fully Risk-Return use Axiom 1 we must decide how to measure risk. As we will see, risk is difficult to measure. Axiom 9 introduces you to the process of diversification and demonstrates how it can reduce risk. We will also provide you with an understanding of how diversification makes it difficult to measure a project or an assets risk.

Figure 3. Reducing risk through diversification.

You are probably already familiar with the concept of diversification. There is an old bably saying dont put all your eggs in one basket. Diversification allows good and bad events or observations to cancel each other out, preferably reducing total variability without a affecting expected return.

To see how diversification complicates the measurement of risk, let us look at the difficulty Louisiana Gas has in determining the level of risk associated with a new natural gas well drilling project. Each year Louisiana Gas might drill several hundred wells, with each well might

having only a 1 in 10 chance of success. If the well produces, the profits are quite large, but if it comes up dry the investment is lost. Thus, with a 90 percent chance of losing everything, we would view the project as being extremely risky. However, if Louisiana Gas each year drills 2000 wells all with a 10 percent, independent chance of success, then they would typically have 200 successful wells. Moreover, a bad year may result in only 190 successful wells, while a good year may result in 210 successful wells. If we look at all the wells together the extreme good and the bad results tend to cancel each other out and the well drilling projects taken together do not appear to have much risk or variability of possible outcome.

The amount of risk in a gas well project depends upon our perspective. Looking at the well standing alone, it looks like a lot; however, if we consider the risk that each well

contributes to the overall firm risk, it is quite small. This occurs because much of the risk associated with each individual well is diversified away within the firm. From the point of view of a diversified shareholder, much of the risk that a project contributes to the firm is further diversified away as the shareholder adds the Louisiana Gas stock to other stocks in his or her portfolio. The risk of an investment varies depending upon the perspective of the individual considering the risk.

Perhaps the easiest way to understand the concept of diversification is to look at it graphically. Consider what happens when we combine two projects as depicted in Figure 4. In this case, the cash flows from these projects move in opposite directions, and when they are combined, the variability of their combination is totally eliminated. Notice that the return has not changed-both the individual projects and their combinations return averages 10 percent. In this case the extreme good and bad observations cancel each other out. The degree to which the total risk is reduced is a function of how the two sets of cash flows or returns move together.

As we will see for most projects and assets, some risk can be eliminated through diversification, while some risk cannot. This will become an important distinction later in our studies. For now, we should realize that the process of diversification can reduce risk, and as a result, measuring a project or an assets risk is very difficult. A projects risk changes depending

on whether you measure: (1) the projects risk when it is standing alone, (2) the amount of risk a project contributes to the stockholders portfolio.

Axiom 10: Ethical Behavior Is Doing the Right Thing, and Ethical Dilemmas Are Everywhere in Finance

Ethics, or rather a lack of ethics in finance, is a recurring theme in the news. During the late 1980s and early 1990s the fall of Ivan Boesky and Drexel, Burnham, Lambert, and the near collapse of Salomon Brothers seemed to make continuous headlines. Meanwhile, the movie Wall Street was a hit at the box office and the book Liars Poker, by Michael Lewis, chronicling unethical behavior in the bond markets, became a best seller. As the lessons of Salomon Brothers and Drexel, Burnham, Lambert illustrate, ethical errors are not forgiven in the business world. Not only is acting an ethical manner morally correct, it is congruent with our goal of maximization of shareholder wealth.

Ethical behavior means doing the right thing. A difficulty arises, however, in attempting to define doing the right thing. The problem is that each of us has his own set of values, which forms the basis for our personal judgments about what is the right thing to do. However, every society adopts a set of rules or laws that prescribe what it believes to be doing the right thing. In a sense, we can think of laws as a set of rules that reflect the values of the society as a whole as they have evolved. For purposes of this text, we recognize that individuals have right to disagree about what constitutes doing the right thing, and we will seldom venture beyond the basic notion that ethical conduct involves abiding by societys rules. However, we will point out some of the ethical dilemmas that have arisen in recent years with regard to the practice of financial management. These dilemmas generally arise when some individual behavior is found to be at odds with the wishes of a large portion of the population even though that behavior is not prohibited by law. Ethical dilemmas can therefore provide a catalyst for debate and discussion, which may eventually lead to a revision in the body of the law. So as we embark on our study of finance and encounter ethical dilemmas, we encourage you to consider the issues and form your own opinion.

Many students as, Is ethics really relevant? This is a good question and deserves an answer. First, although business errors can be forgiven, ethical errors tend to end careers and terminate future opportunities. Why? Because unethical behavior eliminates trust, and without trust business cannot interact. Second, the most damaging event a business can experience is a loss of the publics confidence in its ethical standards. In finance we have seen several recent examples of such events. It was the ethical scandals involving insider trading at Drexel, Burnham, Lambert that brought down that firm. In 1991 the ethical scandals involving attempts by Salomon Brothers to corner the Treasury bill market led to the removal of its top executives and nearly put the company out of business.

Beyond the question of ethics is the question of social responsibility. In general, corporate social responsibility means that a corporation has responsibilities to society beyond the maximization of shareholder wealth. It asserts that a corporation answers to a broader constituency than shareholders alone. As with most debates that center on ethical and moral questions, there is no definitive answer. One opinion is that because financial managers are employees of the corporation, and the corporation is owned by the shareholders, the financial managers should run the corporation in such a way that shareholder wealth is maximized and then allow the shareholders to decide if they would like to fulfill a sense of social responsibility by passing on any of the profits to deserving causes. Very few corporations consistently act in this way. For example, in 1992 Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. announced it would start an ambitious program to give away heart medication to those who cannot pay for them. This announcement came in the wake of an American Heart Association report showing that many of the nations working poor face severe health risks because they cannot afford heart drugs. Clearly, Bristol-Myers Squibb felt it had a social responsibility to provide this medicine to the poor at no cost.

How do you feel about this decision?

A Final Note on the Axioms

Hopefully, these axioms are as much statements of common sense as they are theoretical statements. These axioms provide the logic behind what is to follow. We will build on them and attempt to draw out their implications for decision making. As we continue, try to keep in mind that while the topics being treated may change from chapter to chapter, the logic driving our treatment of them is constant and is rooted in these ten axioms.

Activity 2

Make sure that you have read the previous chapter before answering this activity. DONE? If yes, you may answer the following questions briefly. 1. Enumerate the 10 Axioms that form the basics of Financial Management. a. b. c. d. e. f. g. h. i. j.

2. Among the 10 Axioms / Principles in Financial Management, which one has been applied to your life recently? Is it Axiom 1, Axiom 2, Axiom 9 or other Axioms? Try to share your experience and what actions did you make by posting it in our egroup.

You might also like

- Guidelines For Performance AuditingDocument142 pagesGuidelines For Performance AuditingabekaforumNo ratings yet

- Greek and Roman MythologyDocument31 pagesGreek and Roman MythologyCai04No ratings yet

- Mr. Nam's Dilemma: Choosing the Right Financing StrategyDocument8 pagesMr. Nam's Dilemma: Choosing the Right Financing StrategyCleofe Mae Piñero AseñasNo ratings yet

- ChemosynthesisDocument2 pagesChemosynthesisCai04100% (2)

- Types of Bonds and Bond ValuationDocument45 pagesTypes of Bonds and Bond ValuationOliwa OrdanezaNo ratings yet

- Partnership Formation ProblemsDocument2 pagesPartnership Formation ProblemsLizzeille Anne Amor MacalintalNo ratings yet

- Classification of CostDocument4 pagesClassification of CostSha Heradura AngadNo ratings yet

- Ch15 Management Costs and UncertaintyDocument21 pagesCh15 Management Costs and UncertaintyZaira PangesfanNo ratings yet

- FUNDACC1 - Reviewer (Theories)Document12 pagesFUNDACC1 - Reviewer (Theories)MelvsNo ratings yet

- Term Exam Essay PartDocument1 pageTerm Exam Essay PartCristine Jewel CorpuzNo ratings yet

- Law On Obligation and ContractsDocument6 pagesLaw On Obligation and ContractsFrancis Elaine FortunNo ratings yet

- Investagrams Virtual Trading RIVERADocument3 pagesInvestagrams Virtual Trading RIVERACarlo RiveraNo ratings yet

- CBMEC - Operations Management - PreMidDocument4 pagesCBMEC - Operations Management - PreMidjojie dadorNo ratings yet

- Video ReflectionDocument4 pagesVideo ReflectionXuan LimNo ratings yet

- FM - Cost of CapitalDocument26 pagesFM - Cost of CapitalMaxine SantosNo ratings yet

- Economics PrelimsDocument2 pagesEconomics PrelimsYannie Costibolo IsananNo ratings yet

- FAR Chapter 1 Problem 2Document1 pageFAR Chapter 1 Problem 2jelou ubagNo ratings yet

- Group 5 Case AnalyzationDocument13 pagesGroup 5 Case AnalyzationChristine DiazNo ratings yet

- Cash Flow Statement PreparationDocument6 pagesCash Flow Statement PreparationKrystal Guile DagatanNo ratings yet

- OC & CCC Activity 1-4Document8 pagesOC & CCC Activity 1-4Maria Klaryce AguirreNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Managerial Finance and Financial GoalsDocument3 pagesIntroduction to Managerial Finance and Financial GoalsBai Nilo100% (2)

- STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT GUIDEDocument21 pagesSTRATEGIC MANAGEMENT GUIDEnadineNo ratings yet

- Case 7Document1 pageCase 7jona empalNo ratings yet

- Finman Multiple Choice Reviewer - CompressDocument9 pagesFinman Multiple Choice Reviewer - CompressAerwyna AfarinNo ratings yet

- Business Letter FormatsDocument7 pagesBusiness Letter FormatsMiel Larynz Cadiao AlorroNo ratings yet

- MGT-4 Modules 1-5Document15 pagesMGT-4 Modules 1-5RHIAN B.No ratings yet

- Bullets For Chapter 4 C&CDocument4 pagesBullets For Chapter 4 C&Cgeofrey gepitulanNo ratings yet

- Sharing Firm WealthDocument3 pagesSharing Firm WealthJohn Jasper50% (2)

- GHI Company Comparative Balance Sheet For The Year 2015 & 2016Document3 pagesGHI Company Comparative Balance Sheet For The Year 2015 & 2016Kl HumiwatNo ratings yet

- Accounts Debit Credit: Normal Balance Normal BalanceDocument4 pagesAccounts Debit Credit: Normal Balance Normal BalanceVG R1NG3RNo ratings yet

- Four financial statements in annual reportsDocument2 pagesFour financial statements in annual reportsbrnycNo ratings yet

- Module 1 Week 2 PE 004 Objectives and History in Basketball Darjay PachecoDocument5 pagesModule 1 Week 2 PE 004 Objectives and History in Basketball Darjay PachecoRocelle MalinaoNo ratings yet

- Property, Plant and Equipment Chapter 15Document9 pagesProperty, Plant and Equipment Chapter 15Kiminosunoo LelNo ratings yet

- Foa p1 Module 2 For Bsa & Bsais StudentsDocument64 pagesFoa p1 Module 2 For Bsa & Bsais StudentsMiquel VillamarinNo ratings yet

- Business Transactions AnalysisDocument4 pagesBusiness Transactions AnalysisHello KittyNo ratings yet

- Amusement Taxes Explained - Types, Rates & LiabilitiesDocument3 pagesAmusement Taxes Explained - Types, Rates & LiabilitieslyzleejoieNo ratings yet

- Chap10 (Accounts Receivable and Inventory Management) VanHorne&Brigham, CabreaDocument3 pagesChap10 (Accounts Receivable and Inventory Management) VanHorne&Brigham, CabreaJollibee JollibeeeNo ratings yet

- Horizontal Analysis Interpretation PDFDocument2 pagesHorizontal Analysis Interpretation PDFAlison JcNo ratings yet

- 52170068Document11 pages52170068Joel Christian MascariñaNo ratings yet

- Do You Think Success Is Attainable To All OrganizationsDocument1 pageDo You Think Success Is Attainable To All OrganizationsAllyza San PedroNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Tertiary Education To The Employment Rate in The PhilippinesDocument4 pagesThe Impact of Tertiary Education To The Employment Rate in The PhilippinesTrish BernabeNo ratings yet

- ExpectationsDocument1 pageExpectationsDats DSNo ratings yet

- Chart of Accounts Assets: LiabilitiesDocument50 pagesChart of Accounts Assets: LiabilitiesDiana Rose Orlina100% (1)

- Borrowing Cost DrillDocument2 pagesBorrowing Cost DrillJasmin Rabon0% (1)

- BF ASN InvestmentDocument1 pageBF ASN InvestmentkeuliseutinNo ratings yet

- Module 7 8 Managing Your CreditDocument5 pagesModule 7 8 Managing Your CreditDonna Mae FernandezNo ratings yet

- Business Cup Level 1 Quiz BeeDocument28 pagesBusiness Cup Level 1 Quiz BeeRowellPaneloSalapareNo ratings yet

- 1st Freshmen Tutorial Activity 2Document3 pages1st Freshmen Tutorial Activity 2Stephanie Diane SabadoNo ratings yet

- Teaching Note on Midsouth Chamber of Commerce CaseDocument5 pagesTeaching Note on Midsouth Chamber of Commerce CaseM HAFIDZ RAMADHAN RAMADHAN100% (1)

- Management Advisory Services - FinalDocument8 pagesManagement Advisory Services - FinalFrancis MateosNo ratings yet

- Property, Plant and EquipmentDocument40 pagesProperty, Plant and EquipmentNatalie SerranoNo ratings yet

- Mateo Management GroupDocument23 pagesMateo Management GroupPatricia CamilleNo ratings yet

- If The Profits After Salaries and Bonuses Are To Be Divided Equally, and The Profits OnDocument2 pagesIf The Profits After Salaries and Bonuses Are To Be Divided Equally, and The Profits OnJoana TrinidadNo ratings yet

- Janelle. CHANGE ORIENTATION OF ORGANIZATIONAL DEVELOPMENT.Document4 pagesJanelle. CHANGE ORIENTATION OF ORGANIZATIONAL DEVELOPMENT.Jelyne PachecoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 Initiatives Ethics Reduce CorruptionDocument30 pagesChapter 10 Initiatives Ethics Reduce CorruptionMacalandag, Angela Rose100% (1)

- Module 2 - The Accounting Equation and The Double-Entry SystemDocument41 pagesModule 2 - The Accounting Equation and The Double-Entry SystemJenny Paculaba100% (1)

- 2.6. Retained EarningsDocument5 pages2.6. Retained EarningsKPoPNyx Edits100% (1)

- Ch01 McGuiganDocument31 pagesCh01 McGuiganJonathan WatersNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 The One Lesson of BusinessDocument5 pagesChapter 2 The One Lesson of BusinessSaeym SegoviaNo ratings yet

- Accounting Cycle 1 768 290 Worksheet BSDocument27 pagesAccounting Cycle 1 768 290 Worksheet BSKylene Edelle LeonardoNo ratings yet

- FABM - SCI Quiz 4Document4 pagesFABM - SCI Quiz 4Raidenhile mae VicenteNo ratings yet

- AxiomDocument13 pagesAxiomFrancis Dave Peralta BitongNo ratings yet

- ACIS HO 001 Review of Basic IT Concepts-7Document6 pagesACIS HO 001 Review of Basic IT Concepts-7Cai04No ratings yet

- Olympus Fraud FraudDocument34 pagesOlympus Fraud FraudCai04100% (1)

- Ancient MesopotamiaDocument15 pagesAncient MesopotamiaCai04No ratings yet

- OIlympus Case - Restructuring & FraudDocument10 pagesOIlympus Case - Restructuring & FraudPeter Eka SaputraNo ratings yet

- Ten Axioms That Form The Basics of Financial ManagementDocument16 pagesTen Axioms That Form The Basics of Financial ManagementCai04No ratings yet

- Baroque PeriodDocument8 pagesBaroque PeriodCai04No ratings yet

- 2014 7 6224edecDocument8 pages2014 7 6224edecCai04No ratings yet

- Byzantine ArchitectureDocument10 pagesByzantine ArchitectureCai04No ratings yet

- Introduction To ArchitectureDocument14 pagesIntroduction To ArchitectureCai04No ratings yet

- Ancient Egypt: A Glance Back in TimeDocument22 pagesAncient Egypt: A Glance Back in TimeCai04No ratings yet

- Ancient GreeceDocument16 pagesAncient GreeceCai04No ratings yet

- Accountancy Act and IRR 9298 - v3Document52 pagesAccountancy Act and IRR 9298 - v3Lyndon CastuloNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document14 pagesChapter 1Anonymous DcygsowrNo ratings yet

- Role of Advertising in Promoting Cellular Services in PunjabDocument17 pagesRole of Advertising in Promoting Cellular Services in PunjabCai04No ratings yet

- Revised Withholding Tax TablesDocument1 pageRevised Withholding Tax TablesJonasAblangNo ratings yet

- Solution Chapter 1Document12 pagesSolution Chapter 1Abegail Song Balilo100% (1)

- Internal Control CommunicationsDocument16 pagesInternal Control CommunicationsCai04No ratings yet

- The Significance of Socioeconomic Factors - . .Document12 pagesThe Significance of Socioeconomic Factors - . .Cai04No ratings yet

- At-5915 - Other PSAs and PAPSsDocument11 pagesAt-5915 - Other PSAs and PAPSsPau Laguerta100% (1)

- EpistasisDocument4 pagesEpistasisCai04No ratings yet

- A Basic Introduction To Co-Operatives: Why Co-Ops RockDocument4 pagesA Basic Introduction To Co-Operatives: Why Co-Ops RockCai04No ratings yet

- Accounting For Human Capital: Is The Balance Sheet Missing Something?Document4 pagesAccounting For Human Capital: Is The Balance Sheet Missing Something?Cai04No ratings yet

- Sample ExamsDocument11 pagesSample ExamsCai04No ratings yet

- Credit Cooperative MovementDocument130 pagesCredit Cooperative MovementHanz SadiaNo ratings yet

- Mechanics For Graduate Student PresentationDocument9 pagesMechanics For Graduate Student PresentationCai04No ratings yet

- Asymmetric InformationDocument21 pagesAsymmetric InformationCai04No ratings yet