Professional Documents

Culture Documents

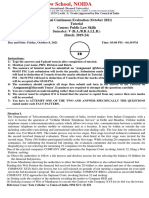

1st Paper

Uploaded by

Hampton ShortOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1st Paper

Uploaded by

Hampton ShortCopyright:

Available Formats

Short P a g e | 1

Hampton Short Professor Randolph AFS 201-04 October 15, 2009. Few lists go on as long as the one that describes Bayard Rustins accomplishments. He saw the travesty of the injustice in the conscientious way of American life. At first glance Bayard looks like your usual civil-rights activist but before the end of his career he changed so much through a vast number of nonviolent protest and even counseling Martin Luther King Jr. on his techniques. His colleagues saw him as a master strategist of social change (D'Emilio 2). Only some have the ability to not only fight for what is right but suffer through all the defeats and still remain one hundred percent dedicated to the end. Bayard Rustin a boy from West Chester, Pennsylvania, raised by his grandparents Janifer Rustin and Julia Davis Rustin. The Rustin house was much like a center for the community with almost constant guest. By the time Rustin was in high school everybody referred to his grandparents as Ma Rustin and Pa Rustin (Levin 8). The house often served as a stop on a second underground railroad during the Great Migration. Bayard grew up seeing his parents as reckless and never had any interest in having a relationship, of any kind, with his father. Bayard attended Wilberforce University, in Ohio, on a music scholarship after high school but drops out and enrolls in Cheyney State Teachers College and leaves, just before his final exams, to New

Short P a g e | 2

York city to get his start with a career where he cant even begin to imagine the things hell see, everything hell say, and how greatly he will affect the civil rights movement. Bayards secret weapon throughout his career was nonviolent direct action, whether or not it got him into trouble didnt matter to him, it was about the message and the change that comes with it. For Rustin nonviolent direct action was much more than just a policy, Its a way of life,(Podair 20) and its certainly not an easy one. Those heavily involved in the protesting even as small as handing out pins by the side of the road often paid greatly with jail time and constantly enduring hurtful comments. However the values held by them did as much for those who lived this life as it did for the ones they sought to help. Bayard, more often than not, choose issues that everyone either didnt know much about or just didnt talk about them. He always tried to distance himself from those in power or had strong influence, by picking the issues that separated himself as an outsider. Sometime coming off as arrogance or superiority so it took a lot from people to really grasp what he was fighting for. It wasnt until later in his career that he really immerged as a civil rights leader . For Jobs and Freedom. That was the theme for the famed march on Washington on August 28, 1963. It was this afternoon that Bayard Rustin stepped forward into the forefront of the Civil Rights movements, and out from his protective shadow. As a head organizer of the event, it was Rustin who put Martin Luther King Jr., speech last and when the coverage of the historical event from LIFE magazine came out it was Bayard Rustin who was put on their cover. Thus the dawn of his public career (Podair 4).

Short P a g e | 3

While the final preparations were being made for the speeches, before the sun even rose, many including Bayard were fearful that not enough people would attend. The media was asking Rustin what would happen if the days plans fell through, he simply responded Gentlemen, everything is exactly on schedule (Levin 144). By that afternoon almost 250,000 showed up with more than just a fiery spirit. Not even the sixteen thousand dollar P.A system was adequate to reach the back of the crowd. A lot of people did not like that Rustin put Martin Luther Kings speech last, but he knew that Once King had spoken, the march would be over.

(Levin 145)

The march on Washington was not his first light in the public mainstream. The Journey of Reconciliation was the first of the Freedom Rides of the 1960s (Anderson 116). This journey was designed to test the new laws passed by the Supreme Court declaring that segregation was unconstitutional. The plan was to take eight white men and 8 black men and travel through the deep south and put these laws to the ultimate test. The black men sat up front and the white men sat in the back. Bayard Rustin and George Houser were the two who headed the trip. The sixteen men left from Washington D.C on April 9 1947 spread out on Greyhound buses and trains, some sitting up front and some in back. The first cities included Richmond, Bristol, Amherst, Charlottesville and on to Nashville. Of the first several stops there was very little conflict. As expected arrest couldnt be avoided forever. The first notable one occurred in Durham, North Carolina. Bayard Rustin, Andrew Johnson, and James Peck were taken off their busses and arrested on account of the Jim Crow Laws. Again in Chapel Hill four of the guys were arrested for violation laws against integrated seating in public conveyances. Only this time when James Peck went to post bail five of the drivers from the buses that were involved

Short P a g e | 4

surrounded him threatening him. His response of non-violence took them all by surprise and was overheard by the famous Reverend Jones of Chapel Hill Presbyterian church. Mr. Jones was inspired to help them by taking them to their next destination. So he first took them back to his own house only to find that they had been followed by a mob of people angry at what was going on. That night there were several threats to burn down his house if he didnt get them out of town who accordingly arrange a safe way out of town for the group (Anderson 116-119). Everywhere they went they were changing the views of the people they encountered, encouraging a need for adjustment of their customs and attitudes. The most notable aspect of the trip came from another arrest in North Carolina when Rustin and Andrew Johnson, two of the black men, were sentenced to thirty days on a chain gang, and Igal Roodenko and Joseph Felmet, both white got ninety days for the same charge from the same judge, Judge Henry Whitfield.

Whitfield justified it on grounds that white liberals were even more objectionable than the

blacks whose cause they espoused (Anderson 122). Most of the accounts of the other men talk of Rustins high spirits, calling him the most colorful figure among us. (Anderson 117) because of his songs on the rides and the speeches he gave at local meetings on the importance of the Supreme Courts decisions. Bayards high-class British accent actually played an important part when giving his presentations in the south. It not only helped his own personal creditability but most in the south were not used to hearing a African American quite like him and they especially were not accustomed to his nonviolent tactics. The Montgomery Boycott was one of many events that Bayard and Martin Luther King worked very closely on. The credit for bringing the boycott to the attention of many white northerners can almost completely be given to Bayard. He published a personal account called

Short P a g e | 5

Montgomery Diary in an article in a magazine, Liberation. It was published under Martin Luther Kings name so it would get more readers and hopefully a more drastic response (Podair 40). As if publishing in a nationally read magazine was no enough, Bayard organized a rally in Madison Square Garden which drew in a crowd of almost twenty thousand. The most influential factor that made the really as strong as it was, was that he pulled in as many organizations as he could, including several labor unions, civil rights groups, NAACP, civil rights activist congressman Adam Clayton Powell to give the keynote address, white liberals like Eleanor Roosevelt. Thanks to all the support the really and the publishing brought in, the boycott was a huge success ending, after over one year, in December 1965 after the Supreme Court declared segregated seating on city buses unconstitutional (Podair 40-43). It was after the boycott that Rustins position in Martin Luther Kings life showed permanence. They started applying nonviolent direct action to other venues, and started a group called the Southern Christian Leadership Conference(SCLC), King becoming the President and face of the group while Rustin shaped the purpose and vision of the group (Podair 45). It was July 2, 1964, that President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act, the biggest step to equality since Lincolns administration (Podair 73). While Bayard Rustins name will never come up when who to credit the Civil Rights Act to, and it will always be Martin Luther King that will be remembered as the face of the civil rights movement, without his support none of these events would have taken place, and even Martin Luther King wouldnt of been as popular as he was. He became the basis for the inspiration in countless individuals through the power of his passion of everything he stood for. Bayard was a strong believer of obtaining civil rights through legislation and through the power of self and he fought for it tirelessly. To Bayard dreams were more than goals, they were possible.

Short P a g e | 6 Works Cited Anderson, Jervis. Bayard Rustin: Troubles I've Seen. 1st. 1. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc, 1997. Print. Chabot, Sean. "Framing and Transnational Diffusion: African-American Intellectuals and the Indian Independence Movement" Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association, Hilton San Francisco & Renaissance Parc 55 Hotel, San Francisco, CA,, Aug 14, 2004. 2009-05-26 <http://www.allacademic.com/meta/p108573_index.html> D'Emilio, John. Lost Prophet the life and times of Bayard Rustin. 1st. 1. New York, NY: Free Press, 2003. Print. Levine, Danial. Bayard Rustin and the Civil Rights Movement. 1st. 1. Bayard Rustin: Bayard Rustin, 2000. Print. Podair, Jerald. Bayard Rustin: American Dreamer. 1st. 1. Plymouth, United Kingdom: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2009. Print.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- MR GMAT Combinatorics+Probability 6EDocument176 pagesMR GMAT Combinatorics+Probability 6EKsifounon KsifounouNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Descartes' Logarithmic Spiral ExplainedDocument8 pagesDescartes' Logarithmic Spiral Explainedcyberboy_875584No ratings yet

- Mil PRF 46010FDocument20 pagesMil PRF 46010FSantaj Technologies100% (1)

- 11th House of IncomeDocument9 pages11th House of IncomePrashanth Rai0% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- A To Z of Architecture PDFDocument403 pagesA To Z of Architecture PDFfaizan100% (1)

- Understanding Death Through the Life SpanDocument52 pagesUnderstanding Death Through the Life SpanKaren HernandezNo ratings yet

- Bill of QuantitiesDocument25 pagesBill of QuantitiesOrnelAsperas100% (2)

- Knowledge and Perception of Selected High School Students With Regards To Sex Education and Its ContentDocument4 pagesKnowledge and Perception of Selected High School Students With Regards To Sex Education and Its ContentJeffren P. Miguel0% (1)

- Folk Tales of Nepal - Karunakar Vaidya - Compressed PDFDocument97 pagesFolk Tales of Nepal - Karunakar Vaidya - Compressed PDFSanyukta ShresthaNo ratings yet

- OCFINALEXAM2019Document6 pagesOCFINALEXAM2019DA FT100% (1)

- Pratt & Whitney Engine Training ResourcesDocument5 pagesPratt & Whitney Engine Training ResourcesJulio Abanto50% (2)

- Gallbladder Removal Recovery GuideDocument14 pagesGallbladder Removal Recovery GuideMarin HarabagiuNo ratings yet

- Margiela Brandzine Mod 01Document37 pagesMargiela Brandzine Mod 01Charlie PrattNo ratings yet

- Commissioning Procedure for JTB-PEPCDocument17 pagesCommissioning Procedure for JTB-PEPCelif maghfirohNo ratings yet

- The Cult of Demeter On Andros and The HDocument14 pagesThe Cult of Demeter On Andros and The HSanNo ratings yet

- Unit Test 1: Vocabulary & GrammarDocument2 pagesUnit Test 1: Vocabulary & GrammarAlexandraMariaGheorgheNo ratings yet

- 100 Commonly Asked Interview QuestionsDocument6 pages100 Commonly Asked Interview QuestionsRaluca SanduNo ratings yet

- 100 Inspirational Quotes On LearningDocument9 pages100 Inspirational Quotes On LearningGlenn VillegasNo ratings yet

- Symbiosis Law School ICE QuestionsDocument2 pagesSymbiosis Law School ICE QuestionsRidhima PurwarNo ratings yet

- Towards A Socially Responsible Management Control SystemDocument24 pagesTowards A Socially Responsible Management Control Systemsavpap78No ratings yet

- Types, Shapes and MarginsDocument10 pagesTypes, Shapes and MarginsAkhil KanukulaNo ratings yet

- 2017 Climate Survey ReportDocument11 pages2017 Climate Survey ReportRob PortNo ratings yet

- Explorations - An Introduction To Astronomy-HighlightsDocument10 pagesExplorations - An Introduction To Astronomy-HighlightsTricia Rose KnousNo ratings yet

- The Names & Atributes of Allah - Abdulillah LahmamiDocument65 pagesThe Names & Atributes of Allah - Abdulillah LahmamiPanthera_No ratings yet

- Colorectal Disease - 2023 - Freund - Can Preoperative CT MR Enterography Preclude The Development of Crohn S Disease LikeDocument10 pagesColorectal Disease - 2023 - Freund - Can Preoperative CT MR Enterography Preclude The Development of Crohn S Disease Likedavidmarkovic032No ratings yet

- Duties of Trustees ExplainedDocument39 pagesDuties of Trustees ExplainedZia IzaziNo ratings yet

- Week 10 8th Grade Colonial America The Southern Colonies Unit 2Document4 pagesWeek 10 8th Grade Colonial America The Southern Colonies Unit 2santi marcucciNo ratings yet

- Ys 1.7 Convergence PramanaDocument1 pageYs 1.7 Convergence PramanaLuiza ValioNo ratings yet

- Station 6 Part 1 2Document4 pagesStation 6 Part 1 2api-292196043No ratings yet