Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Islam and The Challenge of Democracy - Khaled Abu Al Fadal

Uploaded by

api-26176346Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Islam and The Challenge of Democracy - Khaled Abu Al Fadal

Uploaded by

api-26176346Copyright:

Available Formats

To put it more concretely: if a legal opinion is adopted and enforced by the state, it cannot be

said to be God’s law. By passing through the determinative and enforcement processes of the

state, the legal opinion is no longer simply a potential—it has become an actual law, applied

and enforced. But what has been applied and enforced is not God’s law—it is the state’s law.

Effectively, a religious state law is a contradiction in terms. Either the law belongs to the state

or it belongs to God, and as long as the law relies on the subjective agency of the state for its

articulation and enforcement, any law enforced by the state is necessarily not God’s law.

Otherwise, we must be willing to admit that the failure of the law of the state is in fact the

failure of God’s law and, ultimately, of God Himself. In Islamic theology, this possibility cannot

be entertained.25

Of course, the most formidable challenge to this position is the argument that God and His

Prophet have set out clear legal injunctions that cannot be ignored. Arguably, God provided

unambiguous laws precisely because God wished to limit the role of human agency and

foreclose the possibility of innovations. But—to return one last time to a point I have

emphasized throughout—regardless of how clear and precise the statements of the Qur’an and

Sunna, the meaning derived from these sources is negotiated through human agency. For

example, the Qur’an states: “As to the thief, male or female, cut off (faqta‘u) their hands as a

recompense for that which they committed, a punishment from God, and God is all-powerful

and all-wise” (5:38). Although the legal import of the verse seems to be clear, it requires at

minimum that human agents struggle with the meaning of “thief,” “cut off,” “hands,” and

“recompense.” The Qur’an uses the expression iqta‘u, from the root word qata‘a, which could

mean to sever or cut off, but it could also mean to deal firmly, to bring to an end, to restrain, or

to distance oneself from.26 Whatever the meaning derived from the text, can the human

interpreter claim with certainty that the determination reached is identical to God’s? And even

when the issue of meaning is resolved, can the law be enforced in such a fashion that one can

claim that the result belongs to God? God’s knowledge and justice are perfect, but it is

impossible for human beings to determine or enforce the law in such a fashion that the

possibility of a wrongful result is entirely excluded. This does not mean that the exploration of

God’s law is pointless; it only means that the interpretations of jurists are potential fulfillments

of the Divine Will, but the laws as codified and implemented by the state cannot be considered

as the actual fulfillment of these potentialities.

Institutionally, it is consistent with the Islamic experience that the ‘ulama, the jurists, can and

do act as the interpreters of the Divine Word, the custodians of the moral conscience of the

community, and the curators reminding and pointing the nation towards the Ideal that is

God.27 But the law of the state, regardless of its origins or basis, belongs to the state. Under this

conception, no religious laws can or may be enforced by the state. All laws articulated and

applied in a state are thoroughly human and should be treated as such. These laws are a part of

Shari‘ah law only to the extent that any set of human legal opinions can be said to be a part of

Shari‘ah. A code, even if inspired by Shari‘ah, is not Shari‘ah. Put differently, creation, with all

its textual and nontextual richness, can and should produce foundational rights and

organizational laws that honor and promote those rights. But the rights and laws do not mirror

the perfection of divine creation. According to this paradigm, democracy is an appropriate

system for Islam because it both expresses the special worth of human beings—the status of

vicegerency—and at the same time deprives the state of any pretense of divinity by locating

ultimate authority in the hands of the people rather than the ‘ulama. Moral educators have a

serious role to play because they must be vigilant in urging society to approximate God. But

You might also like

- Go Kiss The WorldDocument4 pagesGo Kiss The WorldHarshit0% (1)

- 6632Document208 pages6632ماهر زارعيNo ratings yet

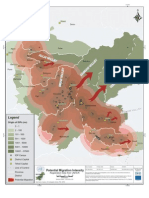

- Map of Movement of IDPsDocument1 pageMap of Movement of IDPsapi-26176346No ratings yet

- Margaret Mohrmann MD Sprituality Ethics and Medicine 032307Document22 pagesMargaret Mohrmann MD Sprituality Ethics and Medicine 032307api-26176346100% (1)

- The Abrahamic FaithsDocument2 pagesThe Abrahamic Faithsapi-2617634650% (2)

- Map of Movement of IDPs 2Document1 pageMap of Movement of IDPs 2api-26176346No ratings yet

- Early Detection of Prostatic CancerDocument7 pagesEarly Detection of Prostatic Cancerapi-26176346No ratings yet

- Breast Cancer Diagnosis Guidelines For Women Over 40Document4 pagesBreast Cancer Diagnosis Guidelines For Women Over 40api-26176346100% (1)

- CK 7 and CK 20 Positive Tumors Modern Pathol 2000Document11 pagesCK 7 and CK 20 Positive Tumors Modern Pathol 2000api-26176346No ratings yet

- Character Analysis (English Version)Document30 pagesCharacter Analysis (English Version)Radhesh Bhoot100% (1)

- Producing Competent Physicians - More Paper Work or IndeedDocument48 pagesProducing Competent Physicians - More Paper Work or Indeedapi-26176346No ratings yet

- Women in Government Cervical Cancer Report 0307Document96 pagesWomen in Government Cervical Cancer Report 0307api-26176346No ratings yet

- NHS UK Breast Screening HindiDocument4 pagesNHS UK Breast Screening Hindiapi-26176346No ratings yet

- Canada - The Supremely BeautifulDocument62 pagesCanada - The Supremely Beautifulapi-26176346No ratings yet

- ATPIIIDocument40 pagesATPIIIXimena OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Radiotherapy Urdu Cancer Backup UKDocument10 pagesRadiotherapy Urdu Cancer Backup UKapi-26176346100% (1)

- Problem ResolutionDocument1 pageProblem Resolutionapi-26176346100% (2)

- Health Status of Immigrants in The USA - NepaleseDocument15 pagesHealth Status of Immigrants in The USA - Nepaleseapi-26176346No ratings yet

- Bengali - Breast Cancer Overview Cancer BackupDocument20 pagesBengali - Breast Cancer Overview Cancer Backupapi-26176346No ratings yet

- Manitoba Breast Cancer Early Detection FarsiDocument2 pagesManitoba Breast Cancer Early Detection Farsiapi-26176346No ratings yet

- NHS UK Breast Screening EnglishDocument12 pagesNHS UK Breast Screening Englishapi-26176346No ratings yet

- Manitoba Breast Cancer Early Detection HindiDocument2 pagesManitoba Breast Cancer Early Detection Hindiapi-26176346No ratings yet

- Ontario Canada Breast Cancer UrduDocument1 pageOntario Canada Breast Cancer Urduapi-26176346No ratings yet

- Bengali - Breast Cancer Chemotherapy Cancer Backup UKDocument10 pagesBengali - Breast Cancer Chemotherapy Cancer Backup UKapi-26176346No ratings yet

- Bengali - Breast Cancer Surgery Cancer Backup UKDocument12 pagesBengali - Breast Cancer Surgery Cancer Backup UKapi-26176346No ratings yet

- Breast Surgery Urdu Cancer Backup UKDocument10 pagesBreast Surgery Urdu Cancer Backup UKapi-26176346No ratings yet

- Bengali - Breast Cancer Radiotherapy Cancer BackupDocument10 pagesBengali - Breast Cancer Radiotherapy Cancer Backupapi-26176346No ratings yet

- Breast Cancer - What Is It - Cancer Backup-UrduDocument20 pagesBreast Cancer - What Is It - Cancer Backup-Urduapi-26176346100% (4)

- Chemo Urdu Cancer Backup UKDocument10 pagesChemo Urdu Cancer Backup UKapi-26176346100% (2)

- Diagnosing and Treating Breast Cancer Arabic UKDocument39 pagesDiagnosing and Treating Breast Cancer Arabic UKapi-26176346100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- C5Document6 pagesC5Tạ Minh ThưNo ratings yet

- Colonial Discourse and Postcolonial Theory PDFDocument2 pagesColonial Discourse and Postcolonial Theory PDFReginaldNo ratings yet

- Alf Ross: On Law and Justice Editor's: Jakob v. H. HoltermannDocument41 pagesAlf Ross: On Law and Justice Editor's: Jakob v. H. HoltermannOsvaldo de la Fuente C.No ratings yet

- 3 - Methods of PhilosophizingDocument5 pages3 - Methods of PhilosophizingJenny RafaelaNo ratings yet

- Module 1 Lesson 1&2Document33 pagesModule 1 Lesson 1&2amerizaNo ratings yet

- Gendron 2005Document38 pagesGendron 2005Daniel WambuaNo ratings yet

- Intro To PolgovDocument6 pagesIntro To PolgovKim Charmaine Galutera100% (1)

- Freire and A Feminist Pedagogy of DifferenceDocument27 pagesFreire and A Feminist Pedagogy of DifferenceMonica PnzNo ratings yet

- Sociology in MeDocument2 pagesSociology in MeQueennie LaraNo ratings yet

- The Law and Its TraditionsDocument16 pagesThe Law and Its TraditionsAnil KumarNo ratings yet

- Whenever A Serious Problem Arises in SocietyDocument9 pagesWhenever A Serious Problem Arises in SocietyafifahyulianiNo ratings yet

- Virtue Ethics CourseDocument47 pagesVirtue Ethics CourseZuzu FinusNo ratings yet

- Important Quotes Political Theory PSIRDocument20 pagesImportant Quotes Political Theory PSIRGoutam ThakuriNo ratings yet

- The Six Approaches To Critiquing A Literary SelectionDocument12 pagesThe Six Approaches To Critiquing A Literary SelectionMary Jane SilvaNo ratings yet

- Jamia Millia Islamia University: Faculty of LawDocument6 pagesJamia Millia Islamia University: Faculty of LawFahwhwhwywwywyywgNo ratings yet

- Hind Swaraj & Concept of SwarajDocument2 pagesHind Swaraj & Concept of SwarajSahil Raj kumarNo ratings yet

- Intro. To Philo. Q2 (Module2)Document8 pagesIntro. To Philo. Q2 (Module2)Bernie P. RamaylaNo ratings yet

- Joseph Alois SchumpeterDocument1 pageJoseph Alois SchumpeterEduard VitușNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 - Personality Lifestyles and ValuesDocument1 pageChapter 7 - Personality Lifestyles and ValuesTIN NGUYEN BUI MINHNo ratings yet

- The Rise of Empiricism and Positivism in 19th Century British History WritingDocument22 pagesThe Rise of Empiricism and Positivism in 19th Century British History WritingMuskan MemonNo ratings yet

- Heidegger Martin - What Is Called ThinkingDocument280 pagesHeidegger Martin - What Is Called Thinkingaifosolifevol100% (12)

- Eric Voegelin - The Formation of The Marxian Revolutionary IdeaDocument29 pagesEric Voegelin - The Formation of The Marxian Revolutionary IdeahenriqueNo ratings yet

- Legal Realism (Holmes)Document4 pagesLegal Realism (Holmes)Jade MangueraNo ratings yet

- Notes in EthicsDocument5 pagesNotes in EthicsEcho MartinezNo ratings yet

- Finis CHPT 1 Evaluation and Description of LawDocument5 pagesFinis CHPT 1 Evaluation and Description of LawDarte Lfc DylanNo ratings yet

- Human Values and Professional Ethics SyllabusDocument2 pagesHuman Values and Professional Ethics Syllabussarojbiswas_skb50% (2)

- Beyond Negativity: What Comes After Gender NihilismDocument7 pagesBeyond Negativity: What Comes After Gender Nihilismwolf gantNo ratings yet

- The Naturte of ConsciousnessDocument167 pagesThe Naturte of ConsciousnessHoang NguyenNo ratings yet

- Utopia PromptDocument2 pagesUtopia PromptRebecca Currence100% (2)

- Book Review: Experience, Caste and The Everyday SocialDocument3 pagesBook Review: Experience, Caste and The Everyday SocialcutkilerNo ratings yet