Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Research

Uploaded by

Cassidy Jordan Reue-CollinsOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Research

Uploaded by

Cassidy Jordan Reue-CollinsCopyright:

Available Formats

Radium

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search This article is about the chemical element. For other uses, see Radium (disambiguation). This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2011)

francium radium actinium

Ba Ra Ub n

88Ra

Appearance silvery white metallic

General properties Name, symbol, number Pronunciation radium, Ra, 88 /redim/

RAY-dee-m

Element category Group, period, block Standard atomic weight Electron configuration Electrons per shell

alkaline earth metal 2, 7, s (226) [Rn] 7s2 2, 8, 18, 32, 18, 8, 2 (Image)

Physical properties Phase Density (near r.t.) Melting point Boiling point Heat of fusion Heat of vaporization solid 5.5 gcm3 973 K,700 C,1292 F 2010 K,1737 C,3159 F 8.5 kJmol1 113 kJmol1

Vapor pressure

P (Pa) at T (K)

1 10 100 819 906 1037

1 k 10 k 1209 1446

100 k 1799

Atomic properties Oxidation states Electronegativity Ionization energies 2 (strongly basic oxide) 0.9 (Pauling scale) 1st: 509.3 kJmol1 2nd: 979.0 kJmol1

Covalent radius Van der Waals radius

2212 pm 283 pm

Miscellanea Crystal structure Magnetic ordering Electrical resistivity Thermal conductivity CAS registry number body-centered cubic nonmagnetic (20 C) 1 m 18.6 Wm1K1 7440-14-4

Most stable isotopes Main article: Isotopes of radium

iso NA half-life DM DE (MeV) Ra trace 11.43 d alpha 5.99 224 Ra trace 3.6319 d alpha 5.789 226 Ra ~100% 1601 y alpha 4.871 228 Ra trace 5.75 y beta 0.046

223

DP Rn 220 Rn 222 Rn 228 Ac

219

v d e

Radium ( /redim/ RAY-dee-m) is a chemical element with atomic number 88, represented by the symbol Ra. Radium is an almost pure-white alkaline earth metal, but it readily oxidizes on exposure to air, becoming black in color. All isotopes of radium are highly radioactive, with the most stable isotope being radium-226, which has a half-life of 1601 years and decays into radon gas. Because of such instability, radium is luminescent, glowing a faint blue. Radium, in the form of radium chloride, was discovered by Marie Skodowska-Curie and Pierre Curie in 1898. They extracted the radium compound from uraninite and published the discovery at the French Academy of Sciences five days later. Radium was isolated in its metallic state by Marie Curie and Andr-Louis Debierne through the electrolysis of radium chloride in 1910. Since its discovery, it has given names like radium A and radium C2 to several isotopes of other elements that are decay products of radium-226.

In nature, radium is found in uranium ores in trace amounts as small as a seventh of a gram per ton of uraninite. Radium is not necessary for living organisms, and adverse health effects are likely when it is incorporated into biochemical processes because of its radioactivity and chemical reactivity.

Characteristics

[edit] Physical characteristics

Although radium is not as well studied as its stable lighter homologue barium, the two elements have very similar properties. Their first two ionization energies are very similar: 509.3 and 979.0 kJmol1 for radium and 502.9 and 965.2 kJmol1 for barium. Such low figures yield both elements' high reactivity and the formation of the very stable Ra2+ ion and similar Ba2+. Pure radium is a white, silvery, solid metal, melting at 700 C (1292 F) and boiling at 1737 C (3159 F), similar to barium. Radium has density of 5.5 gcm3; the radium-barium density ratio is comparable to the radium-barium atomic mass ratio, as these elements have very similar body-centered cubic structures.

[edit] Chemical characteristics and compounds

See also Category: Radium compounds Radium is the heaviest alkaline earth metal; its chemical properties mostly resemble those of barium. When exposed to air, radium reacts violently with it, forming radium nitride,[1] which causes blackening of this white metal. It exhibits only +2 oxidation state in solution. Radium ions do not form complexes easily, due to highly basic character of the ions. Most radium compounds coprecipitate with all barium, most strontium, and most lead compounds, and are ionic salts. The radium ion is colorless, making radium salts white when freshly prepared, turning yellow and ultimately dark with age owing to self-decomposition from the alpha radiation. Compounds of radium flame red-purple and give a characteristic spectrum. Like other alkaline earth metals, radium reacts violently with water and oil to form radium hydroxide and is slightly more volatile than barium, which leads to lesser solubility of radium compounds compared to those of corresponding barium ones. Because of its geologically short half-life and intense radioactivity, radium compounds are quite rare, occurring almost exclusively in uranium ores. Radium chloride, radium bromide, radium hydroxide and radium nitrate are soluble in water, with solubilities slightly lower than those of barium analogs for bromide and chloride, and higher for nitrate. Radium hydroxide is more soluble than hydroxides of other alkaline earth metals, actinium, and thorium, and more basic than barium hydroxide. It can be separated from these elements by their precipitation with ammonia.[1] Out of insoluble radium compounds, radium sulfate, radium chromate, radium iodate, radium carbonate, and radium tetrafluoroberyllate are characterized.[1] Radium oxide, however, remains uncharacterized, despite the fact that other alkaline-earth metals' oxides are common compounds for the corresponding metals.

[edit] Isotopes

Main article: Isotopes of radium Radium has 25 different known isotopes, four of which are found in nature, with 226Ra being the most common. 223 Ra, 224Ra, 226Ra and 228Ra are all generated naturally in the decay of either uranium (U) or thorium (Th). 226Ra is a product of 238U decay, and is the longest-lived isotope of radium with a half-life of 1601 years; next longest is 228Ra, a product of 232Th breakdown, with a half-life of 5.75 years.[2] Radium has no stable isotopes; however, four isotopes of radium are present in decay chains, having atomic masses of 223, 224, 226 and 228, all of which are present in trace amounts. The most abundant and the longestliving one is radium-226, with a half-life of 1601 years. To date, 33 isotopes of radium have been synthesized, ranging in mass number from 202 to 234. To date, at least 12 nuclear isomers have been reported; the most stable of them is radium-205m, with a half-life of between 130 and 230 milliseconds. All ground states of isotopes from radium-205 to radium-214, and from radium-221 to radium-234, have longer ones.

Three other natural radioisotopes had received historical names in the early twentieth century: radium-223 was known as actinium X, radium-224 as thorium X and radium-228 as mesothorium I. Radium-226 has given historical names to its decay products after the whole element, such as radium A for polonium-218.

[edit] Radioactivity

Radium is over one million times as radioactive as the same mass of uranium. Its decay occurs in at least seven stages; the successive main products have been studied and were called radium emanation or exradio (now identified as radon), radium A (polonium), radium B (lead), radium C (bismuth), etc. Radon is a heavy gas, and the later products are solids. These products are themselves radioactive elements, each with an atomic weight a little lower than its predecessor.[3][4] Radium loses about 1% of its activity in 25 years, being transformed into elements of lower atomic weight, with lead being the final product of disintegration.[5] The SI unit of radioactivity is the becquerel (Bq), equal to one disintegration per second. The curie is a non-SI unit defined as that amount of radioactive material that has the same disintegration rate as 1 gram of radium-226 (3.71010 disintegrations per second, or 37 GBq).[6] Radium metal maintains itself at a higher temperature than its surroundings because of the radiation it emits alpha particles, beta particles, and gamma rays. More specifically, the alpha particles are produced by the radium decay, whereas the beta particles and gamma rays are produced by relatively short-half-life elements further down the decay chain.[7]

[edit] Occurrence

Radium is a decay product of uranium and is therefore found in all uranium-bearing ores. (One ton of pitchblende typically yields about one seventh of a gram of radium).[8] Radium was originally acquired from pitchblende ore from Joachimsthal, Bohemia, now located in the Czech Republic. Carnotite sands in Colorado provide some of the element, but richer ores are found in the Congo and the area of the Great Bear Lake and the Great Slave Lake of northwestern Canada.[9] Radium can also be extracted from the waste from nuclear reactors. Large radium-containing uranium deposits are located in Russia, Canada (the Northwest Territories), the United States (New Mexico, Utah and Colorado, for example) and Australia.

[edit] Production

All radium occurring today is produced by the decay of heavier elements, being present in decay chains. Owing to such short half-lives of its isotopes, radium is not primordial but trace. It cannot occur in large quantities due both to the fact that isotopes of radium have short half-lives and that parent nuclides have very long ones. Radium is found in tiny quantities in the uranium ore uraninite and various other uranium minerals, and in even tinier quantities in thorium minerals. The amounts produced were aways relatively small; for example, in 1918 13.6 g of radium were produced in the United states.[10] As of 1954, the total worldwide supply of purified radium amounted to about 5 pounds (2.3 kg).[11]

[edit] History

For more details on this topic, see Marie Curie#New elements. Summary of radium decay products that used to have the word 'radium' in their historical names Historic name Symbol, present name 222 Radium emanation Rn, radon-222 218 Radium A Po, polonium-218 214 Radium C Bi, bismuth-214 214 Radium C1 Po, polonium-214 210 Radium C2 Tl, thallium-210 210 Radium D Pb, lead-210 210 Radium E Bi, bismuth-210

Radium F

210

Po, polonium-210

Radium (Latin radius, ray) was discovered by Marie Skodowska-Curie and her husband Pierre on December 21, 1898 in a uraninite sample. While studying the mineral, the Curies removed uranium from it and found that the remaining material was still radioactive. They then separated out a radioactive mixture consisting mostly of compounds of barium which gave a brilliant green flame color and crimson carmine spectral lines that had never been documented before. The Curies announced their discovery to the French Academy of Sciences on 26 December 1898.[12] The naming of radium dates to circa 1899, from French radium, formed in Modern Latin from radius (ray), called for its power of emitting energy in the form of rays.[13] In 1910, radium was isolated as a pure metal by Curie and Andr-Louis Debierne through the electrolysis of a pure radium chloride solution by using a mercury cathode and distilling in an atmosphere of hydrogen gas.[14] The Curies' new element was first industrially produced in the beginning of the 20th century by Biraco, a subsidiary company of Union Minire du Haut Katanga (UMHK) in its Olen plant in Belgium. UMHK offered to Marie Curie her first gram of radium. It gave historical names to the decay products of radium, such as radium A, B, C, etc., now known to be isotopes of other elements. On 4 February 1936, radium E (bismuth-210) became the first radioactive element to be made synthetically in the United States. Dr. John Jacob Livingood, at the radiation lab at University of California, Berkeley, was bombarding several elements with 5-MEV deuterons. He noted that irradiated bismuth emits fast electrons with a 5-day half-life, which matched the behavior of radium E.[15][16][17][18] The common historical unit for radioactivity, the curie, is based on the radioactivity of 226Ra.

[edit] Applications

Some of the few practical uses of radium are derived from its radioactive properties. More recently discovered radioisotopes, such as 60 Co and 137 Cs, are replacing radium in even these limited uses because several of these isotopes are more powerful emitters, safer to handle, and available in more concentrated form.[19][20] When mixed with beryllium, it is a neutron source for physics experiments.[21]

[edit] Historical uses

Self-luminous white paint which contains radium on the face and hand of an old clock.

Radium hands in darkness Radium was formerly used in self-luminous paints for watches, nuclear panels, aircraft switches, clocks, and instrument dials. A typical self-luminous watch that uses radium paint contains around 1 microgram of radium. [11] In the mid-1920s, a lawsuit was filed by five dying "Radium Girl" dial painters who had painted radiumbased luminous paint on the dials of watches and clocks. The dial painters' exposure to radium caused serious health effects which included sores, anemia, and bone cancer. This is because radium is treated as calcium by the body, and deposited in the bones, where radioactivity degrades marrow and can mutate bone cells. During the litigation, it was determined that company scientists and management had taken considerable precautions to protect themselves from the effects of radiation, yet had not seen fit to protect their employees. Worse, for several years the companies had attempted to cover up the effects and avoid liability by insisting that the Radium Girls were instead suffering from syphilis. This complete disregard for employee welfare had a significant impact on the formulation of occupational disease labor law.[22] As a result of the lawsuit, the adverse effects of radioactivity became widely known, and radium-dial painters were instructed in proper safety precautions and provided with protective gear. In particular, dial painters no longer shaped paint brushes by lip (which led to accidental ingestion of the radium salts). Radium was still used in dials as late as the 1960s, but there were no further injuries to dial painters. This further highlighted that the plight of the Radium Girls was completely preventable. After the 1960s, radium paint was first replaced with promethium paint, and later by tritium bottles which continue to be used today. Although the beta radiation from tritium is potentially dangerous if tritium is ingested, tritium has replaced radium in these applications. Radium was once an additive in products such as toothpaste, hair creams, and even food items due to its supposed curative powers.[23] Such products soon fell out of vogue and were prohibited by authorities in many countries after it was discovered they could have serious adverse health effects. (See, for instance, Radithor or Revigator types of "Radium water" or "Standard Radium Solution for Drinking".) Spas featuring radium-rich water are still occasionally touted as beneficial, such as those in Misasa, Tottori, Japan. In the U.S., nasal radium irradiation was also administered to children to prevent middle-ear problems or enlarged tonsils from the late 1940s through the early 1970s.[24] In 1909, the famous Rutherford experiment used radium as an alpha source to probe the atomic structure of gold. This experiment led to the Rutherford model of the atom and revolutionized the field of nuclear physics. Radium (usually in the form of radium chloride) was used in medicine to produce radon gas which in turn was used as a cancer treatment; for example, several of these radon sources were used in Canada in the 1920s and 1930s.[25] The isotope 223 Ra is currently under investigation for use in medicine as a cancer treatment of bone metastasis.

[edit] Precautions

Radium is highly radioactive and its decay product, radon gas, is also radioactive. Since radium is chemically similar to calcium, it has the potential to cause great harm by replacing calcium in bones. Exposure to radium can cause cancer and other disorders, because radium and its decay product radon emit alpha particles upon

their decay, which kill and mutate cells. The dangers of radium were apparent from the start. The first case of so-called "radium-dermatitis" was reported in 1900, only 2 years after the element's discovery. The French physicist Antoine Becquerel carried a small ampoule of radium around in his waistcoat pocket for 6 hours and reported that his skin became ulcerated. Marie Curie also had a similar incident in which she experimented with a tiny sample that she kept in contact with her skin for 10 hours and noted how an ulcer appeared, although not for several days.[26] Handling of radium has also been blamed for Curie's death due to aplastic anemia. Stored radium should be ventilated to prevent accumulation of radon. Emitted energy from the decay of radium also ionizes gases, affects photographic plates, and produces many other detrimental effects to the extent that at the time of the Manhattan Project in 1944, the "tolerance dose" for workers was set at 0.1 microgram of ingested radium.[27][28]

United States Radium Corporation

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search The United States Radium Corporation was a company, most notorious for its operations between the years 1917 to 1926 in Orange, New Jersey, in the United States that led to stronger worker protection laws. After initial success in developing a glow-in-the-dark radioactive paint, the company was subject to several lawsuits in the late 1920s in the wake of severe illnesses and deaths of workers (the Radium Girls) who had ingested radioactive material when they licked their brushes to paint the thin lines and other details on the faces of clocks, watches and other instruments. The workers had been told that the paint was harmless.[1] During World War I and World War II, the company produced luminous watches and gauges for the United States Army for use by soldiers.[2] U.S. Radium was the subject of major radioactive contamination of its workers, primarily women who painted the dials of watches and other instruments with luminous paint.[1]

Contents

[hide]

1 History 2 Immediate aftermath 3 Superfund site 4 See also 5 References 6 External links

[edit] History

The company was founded in 1914 in Newark, New Jersey by Dr. Sabin Arnold von Sochocky and Dr. George S. Willis, and was originally called the Radium Luminous Material Corporation. The company produced uranium from carnotite ore and eventually moved into the business of producing radioluminescent paint. The company then moved to Orange in 1917 and four years later opened its doors as United States Radium Corporation in 1921. By 1926 carnotite ore processing ceased. After the 1970s, the company called itself the Safety Light Corporation, a reference to glow-in-the-dark safety signs, dials and other luminous paint products the company produced. A successor company, Isolite, still produces luminous signs using tritium. The luminescent paint used by the women, a product called Undark, had radium as its main ingredient. Workers had been instructed to "point" the brushes by licking them with their mouths.[3] Unbeknownst to the women, the product was highly radioactive and therefore, carcinogenic. The ingestion of the paint by the women, brought about while licking the brushes, resulted in a condition called radium jaw, a painful swelling and porosity of the upper and lower jaws, and ultimately led to the deaths of many of these women.

Radium jaw (Radium necrosis), was allegedly known and initially denied by US Radium's management and scientists working for the company. This was the reason for litigation against US Radium by the so-called Radium girls. The unfavorable publicity generated by reports of illness and death amongst previous dial painters resulted in a drop in potential employees. Around 1920, a similar dial painting business, a division of the Standard Chemical Company based in Chicago, known as the Radium Dial Company opened in Chicago, but soon moved its dial painting operation to Peru, Illinois to be closer to its major customer, the Westclox Clock Company. Even though several previous workers died and health risks associated with radium were allegedly known, this company continued dial painting operations until 1940, when the operation was moved to New York City.

[edit] Immediate aftermath

The chief medical examiner of Essex County, New Jersey published a report in 1925 that identified the radioactive material the women had ingested as the cause of their bone disease and aplastic anemia, and ultimate death.[2] Illness and death resulting from ingestion of radium paint and the subsequent legal action taken by the women forced closure of the company's Orange facility in 1927. The case was settled out of court in 1928, but not before a substantial number of the litigants were seriously ill or had died from bone cancer and other radiationrelated illnesses.[4] The company, it was alleged, were taking too much time to settle the litigation on purpose, leading to further deaths. In November 1928, Dr. von Sochocky, the inventor of the radium-based paint, died of aplastic anemia resulting from his exposure to the radioactive material, "a victim of his own invention."[5] The victims were so contaminated that radiation can still be detected at their graves, using a Geiger counter.[3]

The Second River flows past the factory site The new worker safety laws in the wake of the lawsuit resulted in safety procedures and training for dial painters. Even though radium paint was used extensively during World War II, and was not discontinued until the late 1960s, no more dial painters suffered radium sickness, thus demonstrating how easily preventable the plight of the "Radium Girls" was.

[edit] Superfund site

The company processed about 1,000 pounds of ore daily while in operation, which was dumped on the site. The radon and radiation resulting from the 1,600 tons of material on the abandoned factory resulted in the site's designation as a Superfund site by the United States Environmental Protection Agency in 1983.[6] From 1997

through 2005, the EPA remediated the site in a process that involved the excavation and off-site disposal of radium-contaminated material at the former plant site, and at 250 residential and commercial properties that had been contaminated in the intervening decades.[7]

The doors of Justice are barred to the "doomed radium victims" by "statute of limitations, summer vacation, postponement," in this May 20, 1928 New York World editorial cartoon.

RECENT NEWS The radium girls finally got some recognition. On Labor Day, 2011, a statue is unveiled in their memory in Ottawa IL, one of several locations where radium watch dial painters worked. Madeline Piller, daughter of the sculptor, and two original workers from factory, Pauline Fuller (C) and June Menne (R), are shown with the statue Sept. 2, 2011. Photo by Tom Sistak from Voice of America. Chicago Mag also has a great article and video on the Radium Girls. Stuff you missed in history class featured the Radium Girls in their Sept. 7, 2011 podcast. And Moment of Science has a script on the radium girls in the works. Also, musician Pat Burtis wrote a song and dedicated a record album to the Radium Girls a few years back.

INTRODUCTION

Grace Fryer and the other women at the radium factory in Orange, New Jersey, naturally supposed that

they were not being poisoned. It was a little strange, Fryer said, that when she blew her nose, her handkerchief glowed in the dark. But everyone knew the stuff was harmless. The women even painted their nails and their teeth to surprise their boyfriends when the lights went out. They all had a good laugh, then got back to work, painting a glow-in-the-dark radium compound on the dials of watches, clocks, altimeters and other instruments. Grace started working in the spring of 1917 with 70 other women in a large, dusty room filled with long tables. Racks of dials waiting to be painted sat next to each woman's chair. They mixed up glue, water and radium powder into a glowing greenish-white paint, and carefully applied it with a camel hair brush to the dial numbers. After a few strokes, the brushes would lose their shape, and the women couldn't paint accurately. "Our instructors told us to point them with our lips," she said. "I think I pointed mine with my lips about six times to every watch dial. It didn't taste funny. It didn't have any taste, and I didn't know it was harmful." (1) Nobody knew it was harmful, except the owners of the U.S. Radium Corporation and scientists who were familiar with the effects of radium. Those days, most people thought radium was some kind of miracle elixir that could cure cancer and many other medical problems. Grace quit the factory in 1920 for a better job as a bank teller. About two years later, her teeth started falling out and her jaw developed a painful abscess. The hazel eyes that had charmed her friends now clouded with pain. She consulted a series of doctors, but none had seen a problem like it. X-ray photos of her mouth and back showed the development of a serious bone decay. Finally, in July 1925, one doctor suggested that the problems may have been caused by her former occupation. As she began to investigate the possibility, Columbia Close-up of the workshop, this one in Ottawa, Ill. University specialist Frederick Flynn, who said (Courtesy Argonne National Lab). he was referred by friends, asked to examine her. The results, he said, showed that her health was as good as his. A consultant who happened to be present emphatically agreed. Later, Fryer found out that this examination was part of a campaign of misinformation started by the U.S. Radium Corporation. The Columbia specialist was not licensed to practice medicine -- he was an industrial toxicologist on contract with her former employer. The colleague had no medical training either -- he was a vice president of U.S. Radium.2 Grace Fryer probably would have been another unknown victim of a bizarre new occupational disease if it had not been for an organization called the Consumers League and journalist Walter Lippmann, an editor with the New York World. Formed in 1899, the Consumers League fought for an end to child labor, a safe workplace and minimum pay and decent working hours for women.3 Lippmann was a crusading journalist and former

muckraker who represented a powerful New York newspaper at a time when New York newspapers were arguably the most influential in the country. The Consumers League The request of a city health department official in Orange, New Jersey, brought the Consumers League into an investigation of the suspicious deaths of four radium factory workers between 1922 and 1924. The request was not unprecedented, since league officials had been involved in many official state and federal investigations. The causes of death in the Orange cases were listed as phosphorous poisoning, mouth ulcers and syphilis, but factory workers suspected that the dial painting ingredients had something to do with it. New Jersey Consumers League chairman Katherine Wiley brought in a statistical expert and also contacted Alice Hamilton, a Harvard University authority on workers' health issues. Hamilton was on the league's national board, and as it turned out, she was already involved in another aspect of the same case. A few years earlier, a colleague at Harvard, physiology professor Cecil Drinker, had been asked to study the working conditions at U.S. Radium and report back to the company. Drinker found a heavily contaminated work force, unusual blood conditions in virtually everyone, and advanced radium necrosis in several workers. During the investigation, Drinker noticed that U.S. Radium's chemist, Edward Lehman, had serious lesions on his hands. When Drinker spoke to him about the danger in the careless and unprotected the way he handled the radium, he "scoffed at the possibility of future damage," Drinker said. "This attitude was characteristic of those in authority throughout the plant. There seemed to be an utter lack of realization of the dangers inherent in the material which was being manufactured."4 Lehman died a year later. Drinker's June 1924 report recommended changes in procedures to protect the workers, but Arthur Roeder, president of U.S. Radium, resisted the suggestions. In correspondence with Drinker, Roeder raised several points that disputed the physiologist's findings and promised to send along facts to back up the assertions, which he never did. Roeder refused to give the Harvard professor permission to publish his findings about the new radium disease at the plant, insisting that Drinker had agreed to confidentiality. Eventually, U.S. Radium threatened legal action against Drinker.5 Roeder was also in correspondence with Wiley at the Consumers League. Wiley wanted U.S. Radium to pay some of the medical expenses for Grace Fryer and the other employees having problems. Roeder said that Fryer's condition had nothing to do with radium, saying it must be "phospho jaw or something very similar to it." He also accused Wiley of acting in bad faith, saying that a small amount of data from the company was shared with the league in confidence, and he claimed Wiley betrayed his confidence.6

In April 1925, Alice Hamilton wrote to Katherine R. Drinker, also a Ph.D. and a partner with her husband Cecil in their U.S. Radium investigation. The letter, on Hull House stationery, said: "... Mr. Roeder is not giving you and Dr. Drinker a very square deal. I had heard before that he tells everyone he is absolutely safe because he has a report from you exonerating him from any possible responsibility in the illness of the girls, but now it looks as if he has gone still farther... [The New Jersey Department of Labor] has a copy of your report and it shows that 'every girl is in perfect condition.' Do you suppose Roeder could do such as thing as to issue a forged report in your name?" 7

Alice Hamilton, M.D., of Harvard, investigated the case and called Walter Lippmann of the New York World. (Library of Congress).

After this letter, Cecil Drinker realized why Roeder had been stalling him and trying to keep his report from being published. After the Hamilton letter, Drinker sent his original report to the Department of Labor and made arrangements to publish it in a scientific journal, despite U.S. Radium's threats. Meanwhile, a Consumer League consultant trumped the Drinkers by reading a radium necrosis paper at the American Medical Association conference, while the Drinkers fought Roeder for permission over the data.8 The Drinkers finally published their paper later that year, concluding:

"Dust samples collected in the workroom from various locations and from chairs not used by the workers were all luminous in the dark room. Their hair, faces, hands, arms, necks, the dresses, the underclothes, even the corsets of the dial painters were luminous. One of the girls showed luminous spots on her legs and thighs. The back of another was luminous almost to the waist...."9 This casual attitude toward the green radium powder was not matched in other parts of the factory, especially the laboratory, where chemists typically used lead screens, masks and tongs. Yet the company management "in no way screened, protected or warned the dial painters," Fryer's attorney, Raymond Berry, charged. The "radium girls," like many other factory workers at the time, were expendable. Radium's Dangers The scientific and medical literature contained plenty of information about the hazards of radium. Even one of U.S. Radium's own publications, distributed to hospitals and doctors' offices, contained a section with dozens of references labeled "Radium Dangers -- Injurious Effects." Some of the references dated back to 1906. Despite the availability of information on the hazards of radium, it was often seen as a scientific miracle with enormous curative powers. The "radium craze" in America, which began around 1903, familiarized the public with the word "radium." One historian said: "The spectacular properties of this element and its envisioned uses were heralded without restraint in newspapers, magazines and books and by lecturers, poets, novelists, choreographers, bartenders, society matrons, croupiers, physicians and the United States government." Stomach cancer could be cured, it was imagined, by drinking a radium concoction that bathed the affected parts in "liquid sunshine."10 One of the medical drinks sold over the counter until 1931, "Radithor," contained enough radium to kill hundreds or possibly thousands of unsuspecting health enthusiasts who drank it regularly for several years.11 An overview of newspaper and magazine articles on radium in the first decades of the 20th century found their tone strongly positive.12

Even when hazards emerged in mainstream press coverage, the benefits usually outweighed the dangers. For instance, the death of French scientist J. Bergonie in November, 1924, provoked a spate of news articles extolling the "martyrs to science" who died experimenting with the element. The New York World counted 140 scientists who, like Bergonie, had given their lives for humanity. The sacrifice had been worthwhile, the newspaper said: "Nowadays, tested precautions make the manipulation of radium or the use of x-rays as innocuous to both operator and patient as the pounding of a typewriter... The exploration has cost many Radithor, a miracle cure for -- and cause of -- cancer. lives and untold agonies, but the martyrs would undoubtedly be the first to (Courtesy Argonne National Lab). assert that the gain in knowledge had been worth the price. Both discoveries are now thoroughly established as safe, healing agencies of the utmost value."13 Many scientists felt threatened by the idea that radium could cause, rather than cure, cancer. "If radium has unknown dangers, it might seriously injure the therapeutic use of radium," Charles Norris, chief medical examiner of New York, wrote Raymond Berry during Fryer's lawsuit.14 An ore agent and former partner in U.S. Radium also wrote to Berry: "Thousands in Germany have been taking radium salts, admixed with bicarbonate of soda, as a vital stimulant," he said. The bone afflictions of the "radium girls" was probably produced by the glue or another ingredient, but "radium could not produce the results ascribed to it."15 The Lawsuit Although it meant flying in the face of some medical opinion, Grace Fryer decided to sue U.S. Radium, but it took her two years to find an attorney willing to take the case. On May 18, 1927, Raymond Berry, a young Newark attorney, took the case on contingency and filed a lawsuit in a New Jersey court on her behalf. Four other women with severe medical problems quickly joined the lawsuit. They were Edna Hussman, Katherine Schaub, and sisters Quinta McDonald and Albina Larice. Each asked for $250,000 in compensation for medical expenses and pain. The five eventually became known in newspaper articles carried in papers throughout the U.S. and Europe as "the Radium Girls." The first legal hurdle was New Jersey's two-year statute of limitations. Berry contended that the statute applied from the moment the women learned about the source of their problems, not from the date they quit working for U.S. Radium. Berry alleged that U.S. Radium's misrepresentation of scientific opinion and campaign of

misinformation was the reason that the women were not informed and did not take legal action within the statute of limitations. While Berry and the company skirmished in court, medical examiners from New Jersey and New York continued to investigate the suspicious deaths of plant workers. Amelia Maggia, a former dial painter and sister of two of the Radium Girls, McDonald and Larice, died in 1922 from what was said to be syphilis and was buried in Rosemont Cemetery in Orange. She had been treated by a New York dentist, Joseph P. Knef, who had removed Maggia's decayed jawbone some months before she died. "Before Miss Maggia's death I became suspicious that she might be suffering from some occupational disease," Knef said. At first he suspected phosphorous, which produced the notorious "phossy jaw" necrosis common among match makers in the early 18th century. "I asked the radium people for the formula of their compound, but this was refused," Knef said. "After the girl's death so many other persons were sent to me with almost similar symptoms that I became more suspicious, and took up the study of radium with an expert."16 In 1924, Knef wrapped the jawbone in unexposed dental film for a week and then developed the film. He also checked the bone with an electroscope to confirm its radioactivity and then wrote a paper with the Essex County medical examiner identifying radium necrosis.17 In the words of a Newark, N.J., newspaper: "Dr. Knef then described how radium, hailed as a boon to mankind in treatment of cancer and other diseases, becomes a subtle death-dealing menace." An autopsy could confirm Knef's findings, and after a formal request by the Maggia sisters and Raymond Berry, Amelia's body was exhumed on October 16, 1927. An investigation confirmed that her bones were highly radioactive. Clearly, Maggia had not died of syphilis, but of the new and mysterious necrosis that was also killing her sisters. The Media Coverage Only after the case of the New Jersey women was legitimized in a courtroom setting -- a formal structure for news gathering -- did the larger media outlets pick up the story. And they did so with a mix of sensationalism and muckraking, accelerating the issue. In the fall of 1927, an enterprising Star Eagle reporter found that U.S. Radium had reached out-of-court settlements with the families of other radium workers in 1926, paying a total of $13,000 in three cases.18 Legal maneuvers filled 1927, and the medical condition of the five women worsened considerably. The two sisters were bedridden, and Grace Fryer had lost all of her teeth and could not sit up without the use of a back brace, much less walk. When the first court hearing came up January 11, 1928, the women could not raise their arms to take the oath. All five of the "Radium Girls" were dying. "When pretty Grace Fryer took the witness stand, she said her health had been good until after she had been employed at the radium plant," one news account said. Fryer and the others bravely tried to keep smiling, but friends and spectators in the courtroom wept. Edna Hussman told the court about the financial troubles the medical bills were causing: "I cannot even keep my little home, our bungalow," she said. "I know I will not live much longer, for now I cannot sleep at night for the pains." She was content, however, because her children would be cared for by relatives.19 The news media suddenly found the story irresistible. Headlines included: "Woman Awaiting Death Tells How Radium Poison Slowly, Painfully Kills"20 and "Would You Die for Science? Some Would."21 The newspapers followed the twists and turns in the case, particularly the suffering of the women, the disappearing hope for a cure and the company's defense. One of the macabre fascinations with the "Radium Girls" story was how -assuming the women won the lawsuit -- one might spend a quarter million dollars with only a year to live. One enterprising newspaper asked 10 randomly selected women what they would do. Most of the responses involved spending sprees and charity donations.22 By April, the women were not physically or mentally able to attend a second hearing in court. Their attorney was caustic: "When you have heard that you are going to die, that there is no hope -- and every newspaper you pick up prints what really amounts to your obituary -- there is nothing else," Berry said.23 French scientist Marie Curie, the discoverer of radium, read about the case and told papers in her home country that she had never heard of anything like it, "not even in wartime when countless factories were employed in work dealing with radium." French radium workers used small sticks with cotton wadding rather than paintbrushes, she said. Although the five New Jersey women could eat raw liver to help counteract the anemia-

like effects of radiation sickness, they should not hope for a cure for radium poisoning. "I would be only too happy to give any aid that I could," Curie said. However, "there is absolutely no means of destroying the substance once it enters the human body."24 A local newspaper said Madame Curie had "affirmed the doom already sounded by leading medical authorities who have examined the girls." The predictable reaction, the paper said, was that "some of the victims were prostrated with grief last night when they received the news."25 Curie heard about the reaction and, on June 4, said: "I am not a doctor, so I cannot venture an opinion on whether the New Jersey girls will die. But from newspaper descriptions of the manner in which they worked, I think it imperative to change the method of using radium."26 Curie herself died of radium poisoning in 1934. Time was running out, and Berry, Wiley, Hamilton and others had long been concerned that legal maneuvering would delay justice until well after the women were dead. As anticipated, U.S. Radium did not hesitate to use delaying tactics. After the hearing on April 25, 1928, the Chancery court judge adjourned the case until September despite Berry's strenuous objections. Berry reminded the judge that the women were dying, and might not live until September. Berry also found lawyers with cases scheduled in less than a month who were willing to take a September court date to give the "Radium Girls" their day in court. But U.S. Radium attorneys said that their own witnesses would not be available as many were going to Europe for the summer on vacation, and the judge insisted on continuing the case until September. Walter Lippmann and the New York Press The blizzard of publicity surrounding the case worried some medical consultants. "Can you get the [newspapers] to agree to keep the women out of the paper henceforth?" one doctor wrote Berry. "We all agreed that this should be done and that the publicity has had a bad effect on the patients. One was quoted as seeing her body glow as she stood before a mirror..."27 Another doctor wrote: "I would certainly not like to have anything the matter with me and be told every few weeks that I was going to die... Surely you realize what the psychological effect of that would be."28 Berry protested: "I am absolutely unconnected, in any way, Walter Lippmann, editor of with newspaper articles which are the New York World newspaper. published. I have endeavored to discourage publicity..."29 In spite of the general disdain for the press on the part of the plaintiffs, a moment arrived in the case when the "Radium Girls" needed a champion. Their physical condition was deteriorating and their financial situation was pitiful. Time was running out. Alice Hamilton had carefully laid out a strategy in the previous months with the editor of one of the nation's most powerful newspapers of the time, the New York World. An avowedly liberal newspaper founded by Joseph Pulitzer, the World championed public health causes as part of its mission to "never lack sympathy with the poor [and] always remain devoted to the public welfare."30 Hamilton's long-time friend was World editor Walter Lippmann; he had already worked with Hamilton, ensuring that coverage of the Ethyl leaded gasoline controversy in 1925 included both sides of the story, including large amounts of copy from university scientists critical of Standard Oil.31 Hamilton had written to Lippmann in 1927 as she formulated strategy. "There is a situation at present which seems to me to be in need of the sort of help which the World gave in the tetra-ethyl affair," Hamilton wrote.32

She got a response. Lippmann wrote to Berry, "Dr. Hamilton has asked The World to interest itself in this case and has told me that you have the necessary documents. I should appreciate it if you could let me see them."33 When the judge continued the case until September, Lippmann stepped out of his normally cool and sober editorial pulpit. This, he said in a May 10, 1928 editorial, was a "damnable travesty of justice... There is no possible excuse for such a delay. The women are dying. If ever a case called for prompt adjudication, it is the case of five crippled women who are fighting for a few miserable dollars to ease their last days on earth..."34 At this point, Frederick B. Flynn, the Columbia University consultant for U.S. Radium, called a press conference and proclaimed that the women could survive and that he found no radioactivity in his tests. Berry refused to comment, saying he would "prefer to try the case in court."35 Lippmann was furious. "To dispute whether they can live four months or four years while lawyers wrangle over technicalities is to make the case more stupendously horrible than ever. The whole thing becomes a legal nightmare when in order to obtain justice five women have to go to court and prove that they are dying while lawyers and experts on the other side to go the newspapers to prove that they may live somewhat longer." Noting that it was U.S. Radium that was holding up proceedings, Lippmann said: "This is a heartless proceeding. It is unmanly, unjust and cruel. This is a case which calls not for fine-spun litigation but for simple, quick, direct justice."36 Lippmann's editorials, Berry's maneuverings, the behind-the-scenes public relations work of Hamilton and others, and the accumulating outrage as represented in headlines convinced the New Jersey court system, and a trial was rescheduled for early June 1928. Thousands of sympathy letters and quack remedies arrived at the women's homes and the office of their attorney. Inject tannin, said one. Drink Venecine health juice, said another. Drink "mazoon," an old world cureall, said a third, but the author did not include the recipe for the potion. The New York Graphic wrote to offer the services of the famous nature healer Bernarr MacFadden in exchange for publicity rights. "Since the medical doctors have given you up, you have nothing to lose and much to again by trying natural methods... Of course, we would expect you to be willing to cooperate with us to the fullest extent and to allow us to give full publicity to the case."37 The Settlement and Its Aftermath With Lippmann and the newspapers outraged and the legal system shifting in favor of the victims, pressure to settle the case built on U.S. Radium. In early June, a federal judge volunteered to mediate the dispute and help reach an out-of-court settlement. Days before the case was to go to trial, Berry and the five "Radium Girls" agreed that each would receive $10,000 and a $600 per year annuity while they lived, and that all medical and legal expenses incurred would also be paid by the company. The agreement also stipulated payment for all future medical expenses, which would be determined by an impartial panel of physicians. Berry was not entirely happy with the settlement, feeling that "the corporation gets a great advantage," although he knew that the women's situation had grown desperate. He was also skeptical of the mediator, U.S. District Court Judge William Clark. "He is, I am sure, a very honorable man and genuinely interested in social problems," but he is "a man whose circumstances in life place him in the employer's camp." Berry was informed that Judge Clark was a stockholder in the U.S. Radium Corporation.38 Meanwhile, the national president of the Consumers League, Florence Kelly, wrote to Alice Hamilton saying she was "haunted" by the "cold blooded murder in industry" that was taking place in the radium case. Kelly led other state chapters of the Consumers League in checking other radium dial plants, including those in Pennsylvania and Illinois. Along with investigating other plants, Kelly and Hamilton agreed that another step needed to be taken. In a meeting in New York City, the medical examiners for New York and New Jersey sat down with Hamilton, Kelly and Berry. The group agreed on a strategy for proposing a general conference on radium factory safety standards to Surgeon General Hugh Cumming of the U.S. Public Health Service. The medical examiners signed a letter proposing the conference, and the New York World supported it editorially. Kelly and her colleague, Josephine Goldmark, visited Lippmann and Goldmark wrote this account of the meeting:39 "The day we visited him in his small office high up in the dome of the old World building was not wholly propitious for detailing our plans. The political campaign of 1928 was in full swing and just at the moment when we reached his office, Mr. Lippmann, as I recollect it, was receiving the first wires from the Democratic

National Convention in Chicago. He listened to us with interest, nevertheless, and promised his full aid as soon as the letter to the surgeon general had been sent. But he counseled delay... [as Kelly put it] Lippmann agreed to help us in every way possible, but warned us that we should injure our case if we attempted to present it publicly before July 4th, after the close of the second presidential convention."40 All agreed to wait for Hamilton's signal, and Hamilton and Lippmann stayed in close touch during those weeks in July 1928. On July 16, as the letter went out, Lippmann wrote in an editorial: "In many aspects the disease is surrounded by mystery which only an expert, impartial and national agency can remove... clearly this is a task for the Public Health Service."41 Other endorsements followed, including one from Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt, a board member with Hamilton on the National Consumers League. Surgeon General Cumming agreed to the conference and called interested parties together on December 20, 1928. The conference agreed that two committees should be set up: one to investigate existing conditions and a second to recommend the best known means of protection for workers. A Public Health Service official, James P. Leake, commended the Consumers League and others who had worked on behalf of public health and worker safety. "By focusing public attention on some of these horrible examples," Leake said, "the broader problems of disease prevention... can be greatly reduced. It was so in the tetra-ethyl lead work." He added: "The martyrdom of a few may save many."42 CONCLUSION The five "Radium Girls" died in the 1920s and 1930s. Their sad fate was sealed when they dipped paintbrushes into radium paint and sharpened the bristles with their mouths. There was a resistance to warnings about the dangers of radium in society -- highlighting the importance in the relationship between ideas and social structure. In addition, radium was seen as part of the arena of science and medicine and as such enjoyed a certain legitimacy that made it almost beyond criticism. Science was seen as having all the answers, and people were reluctant to question it. It was not until Lippmann and other mainstream media outlets became involved in the story -- and that involvement was accelerated by the legitimation of the legal system -- that the Radium Girls finally settled their lawsuit, albeit for $10,000-plus, much less than the $250,000 they had hoped to receive. The Consumers League and the news media as represented by Lippmann may have served the democratic process. Other dial painters from the era survived, and those who worked at radium paint factories in later years were better protected. Goldmark said, "The hazards of another lethal industrial poison were overcome, and the democratic process of government by informed public opinion was again justified."43 The newspapers, with their preference for dramatic events, also served up the victims as part of a daily fare of murder, mayhem and monstrosities. There exists an interesting parallel to the investigative journalism of later in the century. In the book Journalism of Outrage, the authors note a coalition building process between journalists and government officials and/or interest groups in the 1980s.44 In one case, journalists from a Philadelphia newspaper coordinated their efforts with Congressional staff from the very beginning of a project. The interactive nature of the process in the 1920s was evident when Walter Lippmann and Alice Hamilton used each other for their own ends. Lippmanns newspaper was considered liberal and catered to a working class audience, which would appreciate a story like the Radium Girls; Hamilton needed Lippmann and other journalists to meet her goals, including public awareness of workers' safety issues.

Radium Girls

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search

Radium dial painters working in a factory The Radium Girls were female factory workers who contracted radiation poisoning from painting watch dials with glow-in-the-dark paint at the United States Radium factory in Orange, New Jersey around 1917. The women, who had been told the paint was harmless, ingested deadly amounts of radium by licking their paintbrushes to sharpen them; some also painted their fingernails and teeth with the glowing substance. Five of the women challenged their employer in a court case that established the right of individual workers who contract occupational diseases to sue their employers.

[edit] United States Radium Corporation

Main article: United States Radium Corporation From 1917 to 1926, U.S. Radium Corporation, originally called the Radium Luminous Material Corporation was engaged in the extraction and purification of radium from carnotite ore to produce luminous paints, which were marketed under the brand name 'Undark'. As a defense contractor, U.S. Radium was a major supplier of radioluminescent watches to the military. Their plant in New Jersey employed over a hundred workers, mainly women, to paint radium-lit watch faces and instruments, believing it to be safe.

[edit] Radiation exposure

The U.S. Radium Corporation hired some 70 women to perform various tasks including the handling of radium, while the owners and the scientists familiar with the effects of radium carefully avoided any exposure to it themselves; chemists at the plant used lead screens, masks and tongs. US Radium had even distributed literature to the medical community describing the injurious effects of radium. The owners and scientists at US Radium, familiar with the real hazards of radioactivity, naturally took extensive precautions to protect themselves.[1] An estimated 4,000 workers were hired by corporations in the U.S. and Canada to paint watch faces with radium. They mixed glue, water and radium powder, and then used camel hair brushes to apply the glowing paint onto dials. The then-current rate of pay, for painting 250 dials a day, was about a penny and a half per dial ($0.26 per dial in today's terms). The brushes would lose shape after a few strokes, so the U.S. Radium supervisors encouraged their workers to point the brushes with their lips, or use their tongues to keep them sharp. For fun, the Radium Girls painted their nails, teeth and faces with the deadly paint produced at the factory.[2] Many of the workers became sick. It is unknown how many died from exposure to radiation. The American factory sites became Superfund cleanup sites.[citation needed]

[edit] Radiation sickness

Many of the women later began to suffer from anemia, bone fractures and necrosis of the jaw, a condition now known as radium jaw. It is thought that the X-ray machines used by the medical investigators may have contributed to some of the sickened workers' ill-health by subjecting them to additional radiation. It turned out at least one of the examinations were a ruse, part of a campaign of disinformation started by the defense contractor.[1] U.S. Radium and other watch-dial companies rejected claims that the afflicted workers were suffering from exposure to radium. For some time, doctors, dentists, and researchers complied with requests from the companies not to release their data. At the urging of the companies, worker deaths were attributed by medical professionals to other causes; syphilis was often cited in attempts to smear the reputations of the women.[3]

[edit] Significance

[edit] Litigation

The story of the abuse perpetrated against the workers is distinguished from most such cases by the fact that the ensuing litigation was covered widely by the media. Plant worker Grace Fryer decided to sue, but it took two years for her to find a lawyer willing to take on U.S. Radium. A total of five factory workers, dubbed the Radium Girls, joined the suit. The litigation and media sensation surrounding the case established legal precedents and triggered the enactment of regulations governing labor safety standards, including a baseline of 'provable suffering'.

[edit] Historical impact

The Radium Girls saga holds an important place in the history of both the field of health physics and the labor rights movement. The right of individual workers to sue for damages from corporations due to labor abuse was established as a result of the Radium Girls case. In the wake of the case, industrial safety standards were demonstrably enhanced for many decades. The case was settled in the fall of 1928, before the trial was deliberated by the jury, and the settlement for each of the Radium Girls was $10,000 ($128,226 in today's terms) and a $600 per year annuity ($7,694 per year in today's terms) while they lived, and all medical and legal expenses incurred would also be paid by the company.

[4][5]

The lawsuit and resulting publicity was a factor in the establishment of occupational disease labor law.[6] Radium dial painters were instructed in proper safety precautions and provided with protective gear; in particular, they no longer shaped paint brushes by lip, and avoided ingesting or breathing the paint. Radium paint was still used in dials as late as the 1960s, but there were no further injuries to dial painters.[citation needed] This served to highlight that the injuries suffered by the Radium Girls were completely preventable.

Former factory site

[edit] Scientific impact

Robley D. Evans made the first measurements of exhaled radon and radium excretion from a former dial painter in 1933. At MIT he gathered dependable body content measurements from 27 dial painters. This information was used in 1941 by the National Bureau of Standards to establish the tolerance level for radium of 0.1 Ci (3.7 kBq).

The Center for Human Radiobiology was established at Argonne National Laboratory in 1968. The primary purpose of the Center was providing medical examinations for living dial painters. The project also focused on collection of information, and, in some cases, tissue samples from the radium dial painters. When the project ended in 1993, detailed information of 2,403 cases had been collected. No symptoms were observed in those dial painter cases with less than 1,000 times the natural 226Ra levels found in unexposed individuals, suggesting a threshold for radium-induced malignancies.[citation needed]

1920s in fashion

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search This article includes a list of references, related reading or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. Please improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (June 2009)

Actors Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford on board the SS Lapland wearing fashions of the early 1920s The 1920s is the decade in which fashion entered the modern era. It was the decade in which women first abandoned the more constricting fashions of past days and began to wear more comfortable clothes (such as short skirts or trousers). Men likewise abandoned highly formal daily attire and even began to wear athletic clothing for the first time. The suits men wear today are still based, for the most part, on those worn in the late 1920s. Their hats were somewhat different. The 1920s are characterized by two distinct period of fashion. In the early part of the decade, change was slow, as many were reluctant to adopt new styles. From 1925, the public passionately embraced the styles associated with the Roaring Twenties. These styles continue to characterize fashion until early in 1932.

Contents

[hide]

1 Overview

2 Womenswear

2.1 The boyish figure 2.2 Style gallery 1920 25 2.3 Style gallery 1926 29

3 Menswear 4 Men's hats

4.1 Style gallery

5 Work clothes 6 Children's fashion 7 See also 8 Notes 9 References and further reading 10 External links

[edit] Overview

After World War I, America entered a prosperous era and, as a result of its role in the war, came out onto the world stage. Social customs and morals were relaxed in the optimism brought on by the end of the war and the booming of the stock market. Women were entering the workforce in record numbers. The nationwide prohibition on alcohol was ignored by many. There was a revolution in almost every sphere of human activity[citation needed], and fashion was no exception. The technological development of new fabrics and new closures in clothing affected fashions of the 20s. Natural fabrics such as cotton and wool were the abundant fabrics of the decade. Silk was highly desired for its luxurious qualities, but the limited supply made it expensive. In the late 19th century, "artificial silk" was first made from a solution of cellulose in France. After being patented in the United States, the first American plant began production of this new fabric in 1910; this fiber became known as rayon. Rayon stockings became popular in the decade as a substitute for silk stockings. Rayon was also used in some undergarments. Many garments before the 1920s were fastened with buttons and lacing, however, during this decade, the development of varieties of metal hooks and eyes meant that there were easier means of fastening clothing shut. Hooks and eyes, buttons, zippers or snaps were all utilized to fasten clothing.

[edit] Womenswear

Elisabeth Gabriele of Bavaria, Queen of Belgium, 1920

Actress Louise Brooks in 1927, wearing bobbed hair under a cloche hat Clothing fashions changed with women's changing roles in society, particularly with the idea of new fashion. Although society matrons of a certain age continued to wear conservative dresses, the sportswear worn by forward-looking and younger women became the greatest change in post-war fashion. The tubular dresses of the 'teens had evolved into a similar silhouette that now sported shorter skirts with pleats, gathers, or slits to allow motion. The straight-line chemise topped by the close-fitting cloche hat became the uniform of the day. Women "bobbed," or cut, their hair short to fit under the popular hats, a radical move in the beginning, but standard by the end of the decade. Low-waisted dresses with fullness at the hemline allowed women to literally kick up their heels in new dances like the Charleston. In the world of art, fashion was being influenced heavily by art movements such as surrealism. After World War I, popular art saw a slow transition from the lush, curvilinear abstractions of art nouveau decoration to the more mechanized, smooth, and geometric forms of art deco. Elsa Schiaparelli is one key Italian designer of this decade who was heavily influenced by the "beyond the real" art and incorporated it into her designs.

[edit] The boyish figure

Undergarments began to transform after World War I to conform to the ideals of a flatter chest and more boyish figure. The women's rights movement had a strong effect on women's fashions. Most importantly, the confining corset was discarded, replaced by a chemise or camisole and bloomers, later shortened to panties or knickers. During the mid-twenties all-in-one lingerie became popular. For the first time in centuries, women's legs were seen with hemlines rising to the knee and dresses becoming more fitted. A more masculine look became popular, including flattened breasts and hips, short hairstyles such as the bob cut, Eton crop and the Marcel Wave. The fashion was bohemian and forthcoming for its age. One of the first women to wear trousers, cut her hair and reject the corset was Coco Chanel. Probably the most influential woman in fashion of the 20th century, Coco Chanel did much to further the emancipation and freedom of women's fashion. Jean Patou, a new designer on the French scene, began making two-piece sweater and skirt outfits in luxurious wool jersey and had an instant hit for his morning dresses and sports suits. American women embraced the clothes of the designer as perfect for their increasingly active lifestyles. By the end of the Twenties, Elsa Schiaparelli stepped onto the stage to represent a younger generation. She combined the idea of classic design from the Greeks and Romans with the modern imperative for freedom of movement. Schiaparelli wrote that the ancient Greeks "gave to their goddesses ... the serenity of perfection and the fabulous appearance of freedom."[citation needed] Her own interpretation produced evening gowns of elegant simplicity. Departing from the chemise, her clothes returned to an awareness of the body beneath the evening gown.

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

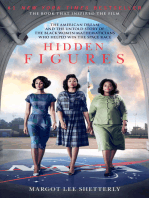

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Spectrophotometry - Absorbance SpectrumDocument3 pagesSpectrophotometry - Absorbance SpectrumSom PisethNo ratings yet

- New IffcoDocument48 pagesNew IffcoDiliptiwariNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Flexible Pipe: Applications and InstallationDocument51 pagesIntroduction to Flexible Pipe: Applications and InstallationpykstvyNo ratings yet

- LAB 14 - One-Dimensional Consolidation - Oedometer - Level 0 - 2ndDocument6 pagesLAB 14 - One-Dimensional Consolidation - Oedometer - Level 0 - 2ndAmirah ShafeeraNo ratings yet

- Bilirubin-D Mindray bs-300Document1 pageBilirubin-D Mindray bs-300neofherNo ratings yet

- F2 = 30 kNm)2/4) 70 × 109 N/m2Document11 pagesF2 = 30 kNm)2/4) 70 × 109 N/m2Don ValentinoNo ratings yet

- Worksheet 2 - TLC - Updated Summer 2021Document4 pagesWorksheet 2 - TLC - Updated Summer 2021Bria PopeNo ratings yet

- Tabela Aço Inox PDFDocument8 pagesTabela Aço Inox PDFjucalele77No ratings yet

- Engineering Design Guideline Separator Vessel Rev01Document28 pagesEngineering Design Guideline Separator Vessel Rev01Yan Laksana50% (4)

- Galvanic and Corrosion Compatibility Dissimilar Metal Corrosion GuideDocument21 pagesGalvanic and Corrosion Compatibility Dissimilar Metal Corrosion Guidehitesh_tilalaNo ratings yet

- Powder Coating at HomeDocument9 pagesPowder Coating at Homepakde jongko100% (1)

- Metrology and MeasurementsDocument58 pagesMetrology and MeasurementsShishir Fawade75% (4)

- Key Design PDFDocument11 pagesKey Design PDFjohn139138No ratings yet

- IPS PressVESTDocument64 pagesIPS PressVESTToma IoanaNo ratings yet

- ENGINEERING DESIGN GUIDELINES Fin Fan Air Cooler Rev Web PDFDocument18 pagesENGINEERING DESIGN GUIDELINES Fin Fan Air Cooler Rev Web PDFeoseos12No ratings yet

- Austenitic Stainless SteelDocument3 pagesAustenitic Stainless SteelGeorge MarkasNo ratings yet

- Indian Standard - Code of Safety For MethanolDocument22 pagesIndian Standard - Code of Safety For Methanolvaibhav_nautiyalNo ratings yet

- Iproof™ High-Fidelity DNA PolymeraseDocument2 pagesIproof™ High-Fidelity DNA PolymerasednajenNo ratings yet

- Che F241 1180Document3 pagesChe F241 1180Govind ManglaniNo ratings yet

- Module 6Document104 pagesModule 6rabih87No ratings yet

- University PhysicsDocument358 pagesUniversity PhysicsAlex Kraemer100% (5)

- V. Divakar Botcha Et al-MRX-2016Document14 pagesV. Divakar Botcha Et al-MRX-2016divakar botchaNo ratings yet

- A Dictionary of ColoursDocument528 pagesA Dictionary of ColoursMohammed Mahfouz78% (9)

- MInirhizotron ThecniquesDocument16 pagesMInirhizotron ThecniquesHector Estrada MedinaNo ratings yet

- Paint Failures Library - PPT (Read-Only)Document75 pagesPaint Failures Library - PPT (Read-Only)Elhusseiny FoudaNo ratings yet

- Separating Mixtures Summative TestDocument4 pagesSeparating Mixtures Summative TestMisael GregorioNo ratings yet

- Surface Preparation and Coating Inspection Report for Tasiast Tailings ThickenerDocument2 pagesSurface Preparation and Coating Inspection Report for Tasiast Tailings ThickenerRekhis OussamaNo ratings yet

- Mitsubishi AcDocument28 pagesMitsubishi AcZeeshanNo ratings yet

- Alloy 286Document6 pagesAlloy 286shivam.kumarNo ratings yet

- The Cassini Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer (Inms) InvestigationDocument119 pagesThe Cassini Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer (Inms) InvestigationDima FontaineNo ratings yet