Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Consumption and Savings-Lesson 4 (Repaired) - New

Uploaded by

Merry Rosalie AdaoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Consumption and Savings-Lesson 4 (Repaired) - New

Uploaded by

Merry Rosalie AdaoCopyright:

Available Formats

Consumption and Savings Consumption is part of demand: The largest sector in the GDP.

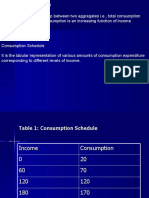

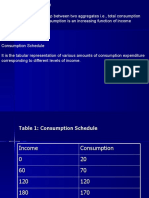

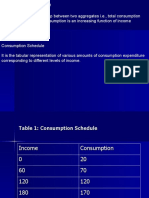

These are the expenditures by households on final goods and services. Saving is that part of personal disposable income that is not consumed. Income, consumption and saving are all closely linked. Example: Disposable Income 24000 25000 26000 27000 28000 29000 30000 Net Saving or dissaving -200 0 200 400 600 800 1000 Consumption 24200 25000 25800 26600 27400 28200 29000

A B C D E F G

The demand for consumption goods is not constant, but rather increases with income. Observation: Families with higher incomes consume more than families with lower incomes and countries where income is higher have higher levels of total consumption. The very poor are unable to save at all, instead, as long as they can borrow or draw down their wealth, they tend to dissave. The break even point- where the representative household neither saves nor dissaves but consume all its income. In the table is at 25000. To understand the consumption and saving induced by each extra unit of income is shown by the consumption function and saving function. Consumption function It shows the relationship between the level of consumption expenditures and the level of disposable income. Consumption demand increases with the level of income. C= + cYd; >0 0<c<1

- intercept, autonomous consumption, represents the level of consumption when income is zero. c- the slope, marginal propensity to consume (mpc). For every unit increase in income, the level of consumption increases by c.

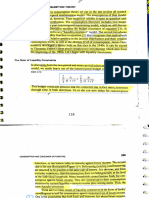

C C= + cY

The break-even point. Because the vertical and horizontal axes have exactly the same scale, the 45 line has a very special property. At any point on the 45 line, the distance up from the horizontal axis exactly equals the distance across from the vertical axis. The 45 line tells us whether consumption spending is equal to, greater than or less than the disposable income. The break-even point is the intersection of the consumption and the 45. So, when the consumption function lies above the 45, the household is dissaving and if below, the household has positive saving. Saving function It shows the relationship between the level of saving and income. It is the vertical distance between the 45 line and the consumption function. Marginal Propensity to Consume Shows the response of consumption to changes in income. It is the extra amount that people consume when they receive an extra dollar of disposable income. It is also the slope of the consumption function, which measures the change in consumption per unit change in disposable income. Marginal Propensity to Save The fraction of an extra dollar of disposable income that goes to extra saving. MPS + MPC = 1

Example: If c=0.9, for every 1 unit increase in income, consumption increases by 0.90. The rest that is not spent in consumption is saved. S= Y C To solve for the savings function; Combine; C= + c Y and S= Y C, S= Y C S= Y ( + cY) S= Y cY + (1 c)Y ----- savings function

S=

Note: Saving is an increasing function of the level of income because the mps (marginal propensity to save). s= 1 c, is positive. Saving increases as income rises. Example: mpc= 0.9, 90 centavos is consumed. How much is saved? s= 1 c ----- s= 1 0.9 ------ s= 0.1

Solve for the MPC and MPS Disposable Income 24000 25000 26000 27000 28000 29000 30000 Net Saving or dissaving -200 0 200 400 600 800 1000 Consumption 24200 25000 25800 26600 27400 28200 29000

A B C D E F G

Consumption Theories Keynes and the Consumption Function Three properties: a. The marginal propensity to consume (c) is between zero and 1 ( 0 < c < 1) b. Average propensity to consume (the ratio of consumption to income) falls as income rises. c. Consumption is determined by current income.

apc= C/ Y = C/Y + c

As Y rises, C/Y falls; apc falls.

45 degree line where income=spending

C C= + cY

Real Disposable Income

Simon Kuznets and Consumption Puzzle He constructed new aggregate data on consumption and investment on 1869. He discovered that the ratio of consumption to income was stable over time, despite large increases in income, Keynes conjecture was called into question. This brings us to puzzle.

The short-time series study of Keynes failed when applied to long time series. Studies of household data and short time-series found a relationship between consumption and income similar to the one Keynes conjectured this is called the short-run consumption function. But, studies using long time-series found that the APC did not vary systematically with income-this relationship is called the long-run consumption function.

Irving Fisher and Intertemporal Choice Fisher developed the model with which economists analyze how rational, forward looking consumers make intertemporal choices or choices involving different periods of time. The model clarifies: a. The constraint consumers face b. Preferences they have c. How these constraints and preferences together determine their choices on consumption and saving When consumers decides how much to consume today versus in the future, they face an intertemporal budget constraint (measures the total resources available for consumption today and in the future).

Franco Modigliani and the Life-Cycle Hypothesis According to Fishers model, consumption depends on a persons lifetime income. Modigliani emphasized that income varies systematically over peoples lives and that saving allows consumers to move income from those times in life when income is high to those times when income is low. This interpretation of consumer behavior formed the basis of his life-cycle hypothesis.

The Hypothesis The consumption function assumes that individuals consumption behavior in a given period is related to their income in that period. It views, individuals, instead, as planning their consumption and savings behavior over long periods with the intention of allocating their

consumption in the best possible way over their entire lifetimes. It implies different marginal propensities to consume out of a permanent income, transitory income and wealth. The key assumption: most people choose stable lifestyles, meaning they consume at about the same level in every period. Example: The person starts life at age 20, and will work until 65 and will die at age 80. The annual labor income, YL= 30,000. WL= 45 (years of working). YL x WL=30,000 x 45 =1,350,000 Number of years of life (NL= 80-20= 60) allows annual consumption of C= 1350000 / 60 = 22,500 C= WL/NL x YL The marginal propensity to consume is WL/NL. MPC out of permanent income is large and MOC out of transitory income is small. Example: Permanent rise in income- 3,000 per year =3000 x (45/60) =2250 The mpc out of YP would be WL/NL (45/60= .75) Transitory income- 3,000 = 3000 x (1/60) =50 The mpc would be (1/60=.017). The model implies that mpc out of wealth should be equal mpc out of YT

The Life-Cycle Model

Consumption is constant throughout lifetime. During the working life, especially the last WL; the individual saves by accumulating assets. At the end of WL, the individual begins to liveoff these assets, dissaving for the remaining years (NL-WL) of life such that assets= zero at the end.

Milton Friedman and the Permanent Income Hypothesis In 1957, Milton Friedman proposed the permanent-income hypothesis to explain consumer behavior. Its essence is that current consumption is proportional to permanent income. Friedmans permanent-income hypothesis complements Modiglianis life-cycle hypothesis: both use Fishers theory of the consumer to argue that consumption should not depend on current income alone. But unlike the life-cycle hypothesis, which emphasizes that income follows a regular pattern over a persons lifetime, the permanent-income hypothesis emphasizes that people experience random and temporary changes in their incomes from year to year. Current income is the sum of permanent income and transitory income. Y= YP + YT Transitory income- part of income that people do not expect to persist. Example: Consider a person who receives income only once a week (on Fridays). SO, we do not expect that person to consume only on Friday. People prefer a smooth consumption flow rather than plenty today and scarcity tomorrow or yesterday. Permanent income- is the steady rate of expenditure a person could maintain for the rest of his or her life, given the present level of wealth and the income earned now and in the future. C= cYP According to the LC-PIH, consumption should be smoother than income because spending out of transitory income is spread over many years.

Liquidity Constraints and Myopia The LC-PIH miss explaining these two topics- liquidity constraints and myopia. The first argues that when permanent income is higher than current income, consumers are unable to borrow to consume at the higher level predicted by the LC-PIH. The second suggests that consumers simply arent as forward looking at the LC-PIH suggests. Liquidity constraints exists when a consumer cannot borrow to sustain current consumption in the expectation of higher future income. Example: for students, they are looking forward to receive bigger income in the future, as the life-cycle theory stated that they should be consuming base on their lifetime incomes, meaning, they should be spending much more than they currently earn. To suffice their need, they will borrow to support their consumption. Individuals who cannot borrow when their incomes decline temporarily would be liquidityconstrained. Another explanation for the sensitivity of consumption to current income-being myopic. Consumers just spend on what they have, never minding the future.

You might also like

- Insurance and Risk Management NotesDocument11 pagesInsurance and Risk Management NotesNaomi WakiiyoNo ratings yet

- Consumption and SavingDocument6 pagesConsumption and Savingmah rukhNo ratings yet

- Understanding the Consumption FunctionDocument31 pagesUnderstanding the Consumption FunctionDeepak MittalNo ratings yet

- Keynesian Consumption and Investment PDFDocument17 pagesKeynesian Consumption and Investment PDFGayle AbayaNo ratings yet

- Consumption Theory in MacroeconomicsDocument26 pagesConsumption Theory in MacroeconomicsYeshwanth NethaNo ratings yet

- FACTORS THAT SHIFT THE CONSUMPTION FUNCTIONDocument16 pagesFACTORS THAT SHIFT THE CONSUMPTION FUNCTIONIlma LatansaNo ratings yet

- Consumption and Saving FunctionsDocument17 pagesConsumption and Saving FunctionsAndaleeb AmeeriNo ratings yet

- Consumption SavingsDocument13 pagesConsumption SavingsDj I amNo ratings yet

- THE KEYNESIAN CONSUMPTION FUNCTIONDocument47 pagesTHE KEYNESIAN CONSUMPTION FUNCTIONHailegeorgis MaruNo ratings yet

- Consumption, Savings and InvestmentDocument26 pagesConsumption, Savings and InvestmentProfessor Tarun DasNo ratings yet

- Consumption and Savings - 1 1Document8 pagesConsumption and Savings - 1 1Anjelika ViescaNo ratings yet

- Consumption and SavingsDocument17 pagesConsumption and SavingsHardeep SinghNo ratings yet

- CC 9Document8 pagesCC 9Ritam DasNo ratings yet

- Consumption FunctionDocument15 pagesConsumption FunctionRifaz ShakilNo ratings yet

- Consumption FunctionDocument15 pagesConsumption FunctionNave2n adventurism & art works.No ratings yet

- Managerial Economics-II Unit-2 Consumption AnalysisDocument15 pagesManagerial Economics-II Unit-2 Consumption AnalysisNaresh Kumar100% (1)

- LECTURE 5 and 6 - Consumption Savings and InvestmentDocument16 pagesLECTURE 5 and 6 - Consumption Savings and Investmentdavid underscore100% (1)

- 802-2 CDocument17 pages802-2 CMuhammad NomanNo ratings yet

- Consumption, Investment and Income HypothesesDocument38 pagesConsumption, Investment and Income HypothesesisabelNo ratings yet

- Consumption FunctionDocument15 pagesConsumption FunctionNaman LadhaNo ratings yet

- Consumption FunctionDocument15 pagesConsumption FunctionAkshat MishraNo ratings yet

- Consumption and Consumer Expenditure William H.BransonDocument12 pagesConsumption and Consumer Expenditure William H.BransonNajia TasnimNo ratings yet

- Read - Econ Handout ConsumptionDocument8 pagesRead - Econ Handout ConsumptionOnella GrantNo ratings yet

- Consumption Function and Investment Function Chap 2 160218025106 PDFDocument39 pagesConsumption Function and Investment Function Chap 2 160218025106 PDFlizakhanamNo ratings yet

- Consumption and Saving Guide: C, S, MPC, MPSDocument6 pagesConsumption and Saving Guide: C, S, MPC, MPSIvan Jovans LUTTAMAGUZINo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument84 pagesUntitledUTKARSH GUPTANo ratings yet

- Classical and Keynesian Consumption FunctionDocument26 pagesClassical and Keynesian Consumption FunctionSiva VarmaNo ratings yet

- Economics Unit 3Document18 pagesEconomics Unit 3Shoujan SapkotaNo ratings yet

- Unit Iii Consumption FunctionDocument16 pagesUnit Iii Consumption FunctionMaster 003No ratings yet

- Answer 2 Consumption FunctionDocument4 pagesAnswer 2 Consumption FunctionNave2n adventurism & art works.No ratings yet

- Definitions: Consumption FunctionDocument10 pagesDefinitions: Consumption FunctionparnasabariNo ratings yet

- Group 3 EconomicsDocument7 pagesGroup 3 EconomicsAsterisk SoulsNo ratings yet

- Consumption TheoriesDocument19 pagesConsumption TheoriesEmaan AnumNo ratings yet

- Macro Economics 03 - Daily Class Notes - Mission JRF June 2024 - EconomicsDocument25 pagesMacro Economics 03 - Daily Class Notes - Mission JRF June 2024 - Economicskg704939No ratings yet

- Understanding the Keynesian Consumption FunctionDocument4 pagesUnderstanding the Keynesian Consumption FunctionNozeelia BlairNo ratings yet

- Consumption FunctionDocument15 pagesConsumption FunctionLakshayNo ratings yet

- Unit iiiDocument31 pagesUnit iiiSandesh KhatiwadaNo ratings yet

- Consumption PDFDocument11 pagesConsumption PDFJatin KhatriNo ratings yet

- Equilibrium National IncomeDocument61 pagesEquilibrium National IncomeJING LINo ratings yet

- Consumption 6 05042021 110104amDocument31 pagesConsumption 6 05042021 110104amMuhammad SarmadNo ratings yet

- MacroeconomicsDocument19 pagesMacroeconomicsIlker Sevki InanNo ratings yet

- Consumption FunctionDocument10 pagesConsumption FunctionOlawaleeniola0No ratings yet

- Phase 1 & 2: 50% OFF On NABARD Courses Code: NABARD50Document23 pagesPhase 1 & 2: 50% OFF On NABARD Courses Code: NABARD50SaumyaNo ratings yet

- Law of ConsumptionDocument16 pagesLaw of ConsumptionAnkit JoshiNo ratings yet

- Relative Income Hypothesis:: Ri Pi Ri PiDocument5 pagesRelative Income Hypothesis:: Ri Pi Ri PiHillary OdungaNo ratings yet

- EIA2002/EXEE 2111 Macroeconomics Ii: Theories On ConsumptionDocument37 pagesEIA2002/EXEE 2111 Macroeconomics Ii: Theories On ConsumptionAfifNo ratings yet

- Solution Manual For Macroeconomics Principles Applications and Tools 8 e 8th Edition Arthur Osullivan Steven Sheffrin Stephen PerezDocument16 pagesSolution Manual For Macroeconomics Principles Applications and Tools 8 e 8th Edition Arthur Osullivan Steven Sheffrin Stephen PerezVanessaMerrittdqes100% (35)

- Lec 5 ConsumptionDocument24 pagesLec 5 ConsumptionEngvalieNo ratings yet

- Topic 1 - Consumption FunctionDocument13 pagesTopic 1 - Consumption Functionreuben kawongaNo ratings yet

- Consumption and Saving Function: Group MembersDocument23 pagesConsumption and Saving Function: Group MembersSarosh HassanNo ratings yet

- ConsumptionDocument19 pagesConsumptionDipen DhakalNo ratings yet

- Four Major Theories of Consumption BehaviorDocument29 pagesFour Major Theories of Consumption BehaviorAbdul Quadir RazviNo ratings yet

- Ps5 2012 SolutionsDocument9 pagesPs5 2012 SolutionsMatthew ZukowskiNo ratings yet

- Unit 4Document47 pagesUnit 4Nishant KhandharNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER ONE Macroeconomics IIDocument35 pagesCHAPTER ONE Macroeconomics IISamuel tsegazeabNo ratings yet

- CH - 12 Branson ConsuptionDocument5 pagesCH - 12 Branson Consuptionswayamdeep.223061No ratings yet

- Chapter 9Document22 pagesChapter 9DenisNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Macro-Economics Course AssignmentDocument16 pagesIntroduction to Macro-Economics Course AssignmentMuhammad NomanNo ratings yet

- BULLISH MARUBOZU, Technical Analysis ScannerDocument2 pagesBULLISH MARUBOZU, Technical Analysis ScannerNithin BairyNo ratings yet

- 9 Main Differences Between Managerial Economics and Traditional EconomicsDocument4 pages9 Main Differences Between Managerial Economics and Traditional EconomicsDeepak KumarNo ratings yet

- Girish KSDocument3 pagesGirish KSSudha PrintersNo ratings yet

- 2012 BTS 1 AnglaisDocument4 pages2012 BTS 1 AnglaisΔαμηεν ΜκρτNo ratings yet

- Mbe AsDocument2 pagesMbe AsSwati AroraNo ratings yet

- Three Affordable Housing Case Studies Compare Energy UseDocument69 pagesThree Affordable Housing Case Studies Compare Energy UsenithyaNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: Economics 9708/13Document12 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: Economics 9708/13Didier Neonisa HardyNo ratings yet

- Cost Accounting For Ultratech Cement LTD.Document10 pagesCost Accounting For Ultratech Cement LTD.ashjaisNo ratings yet

- Anna Ashram SynopsisDocument3 pagesAnna Ashram Synopsissanskruti kakadiyaNo ratings yet

- EE EconomicsDocument13 pagesEE EconomicsAditya TripathiNo ratings yet

- Complete Integration of The Soviet Economy Into The World Capitalist Economy by Fatos NanoDocument4 pagesComplete Integration of The Soviet Economy Into The World Capitalist Economy by Fatos NanoΠορφυρογήςNo ratings yet

- Economics Class 11 Unit 5 Natural Resources of NepalDocument0 pagesEconomics Class 11 Unit 5 Natural Resources of Nepalwww.bhawesh.com.npNo ratings yet

- Stock Market ScamsDocument15 pagesStock Market Scamssabyasachitarai100% (2)

- The Historical and International Foundations of The Socialist Equality Party Sri LankaDocument50 pagesThe Historical and International Foundations of The Socialist Equality Party Sri LankaSanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- CSR Strategy Development and ImplementationDocument39 pagesCSR Strategy Development and ImplementationgankuleNo ratings yet

- 17 DecDocument7 pages17 DecTanveer GaurNo ratings yet

- Tax Invoice Sandeep D L: Amount After Due Date Due Date Amount Payable Invoice Date Billing PeriodDocument2 pagesTax Invoice Sandeep D L: Amount After Due Date Due Date Amount Payable Invoice Date Billing PeriodSandeep DeshkulkarniNo ratings yet

- Efficient Levels Public GoodsDocument33 pagesEfficient Levels Public GoodsZek RuzainiNo ratings yet

- 4.coverage of Major Imports For Preliminary Release (2023)Document6 pages4.coverage of Major Imports For Preliminary Release (2023)Lano KuyamaNo ratings yet

- National Land Registration Program For GeorgiaDocument10 pagesNational Land Registration Program For GeorgiaUSAID Civil Society Engagement ProgramNo ratings yet

- Sandino and Other Superheroes The Function of Comic Books in Revolutionary NicaraguaDocument41 pagesSandino and Other Superheroes The Function of Comic Books in Revolutionary NicaraguaElefante MagicoNo ratings yet

- XAS-356 Manual Atlas CopcoDocument9 pagesXAS-356 Manual Atlas CopcoGustavo Roman50% (2)

- Roljack (Company Profile)Document20 pagesRoljack (Company Profile)nathan kleinNo ratings yet

- 5 Year Financial Projections for Capital, Borrowings, Income & ExpensesDocument2 pages5 Year Financial Projections for Capital, Borrowings, Income & ExpensesCedric JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Indifference CurveDocument10 pagesIndifference Curveamit kumar dewanganNo ratings yet

- Israel's Development from Nationhood to PresentDocument21 pagesIsrael's Development from Nationhood to PresentAbiodun Ademuyiwa MicahNo ratings yet

- Advanced Accounting Baker Test Bank - Chap011Document67 pagesAdvanced Accounting Baker Test Bank - Chap011donkazotey100% (7)

- WTO - Indian Textile ExportsDocument1 pageWTO - Indian Textile ExportsdarshanzamwarNo ratings yet

- Pre-Filling Report 2017: Taxpayer DetailsDocument2 pagesPre-Filling Report 2017: Taxpayer DetailsUsama AshfaqNo ratings yet

- A-19 BSBA Operations MGTDocument2 pagesA-19 BSBA Operations MGTEnteng NiezNo ratings yet