Professional Documents

Culture Documents

New Working Class Subjects GWS, Enku Ide

Uploaded by

Michael IdeCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

New Working Class Subjects GWS, Enku Ide

Uploaded by

Michael IdeCopyright:

Available Formats

New Working Class Subjects Building Power in the Academic Workplace

Enku MC Ide

Women and Class GWS 600 Dr. Karen Tice The University of Kentucky December 11, 2010

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercialShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA.

Ide, 1 New Working Class Subjects Building Power in the Academic Workplace While many academic workers today face low pay, job insecurity, heavy workloads and constant assessment and oversight, a belief in the availability of tenure to those who work hard has become the opiate of the graduate student masses. This essay is an attempt to understand how neoliberalism has impacted workers in higher education, specifically graduate assistants. As I am a graduate assistant interested in unionizing, I use this exploration to suggest strategies for union growth based in advocating a reformulation of academic workers, especially those nottenured as classed subjects. Amidst current neoliberal reforms impacting all public sectors, including public education, unions have a unique opportunity to address systematic issues by incorporating ideological fight-back against the internalization of neoliberal ideology. Neoliberalism must be understood as a process, as particular elements of free-market economics take center stage in every dimension of social life (Ouellette 2008: 233), influencing both structure and ideology. Studies have tended to focus on one aspect of neoliberalism, either structure or ideology. I propose that each of these analytical lenses is reinforcing, and power must be central to any such analysis. To address this, I take a postpositivist analytic frame, employing Bourdieus concept of cultural capital and habitus as entry points to theorizing organizing strategy among academic workers. NEOLIBERAL STRUCTURES, NEOLIBERAL SUBJECTS Structurally, neoliberalism is characterized by privatization, deregulation, commodification, depoliticazation, and the withdrawal of the state from welfare and other commitments (Heery 2009: 250). This withdrawal is seen directly in spending cuts on public services (Ouellette 2008: 233), including education, healthcare and prisons, as these institutions turn to market reforms for economic solvency, thus strengthening ties to the for-

Ide, 2 profit sector and reinforcing the neoliberal impulses at all levels of analysis. This is closely tied to postmodern economic ideas that have risen with deindustrialization and the financialization of the economy. Financialization is related to deindustrialization in the US economy. As primary and secondary sector jobs (based in extraction and manufacturing industries) have been made redundant through industries technological advances and outsourcing, we have witnessed thirty years of wage stagnation and decline through which working class people have stayed afloat via a magnificent credit system that seemed to know no limits (Aronowitz and Difazzio 2010: xvi), including credit cards, mortgages, and loans. With the decline of these sectors, stable, longterm working class careers have been replaced (but not fully) with jobs marked by low wages and high turnover. With decreasing production of material goods within the United States, profits based on fictitious capital, money with no material basis, [and] a speculation on future economic performance (Aronowitz and Difazzio 2010: xvi), must find other areas of social life in which to invest and produce profits, or a capitalist colonization of .the lifeworlds of public social services, including the communal space of academic freedom that is the educational ideal (Castree and Sparke 2000: 223). According to Foucault, this is not a dichotomous clashing of systems, but rather an outgrowth of complex power relations that influence both organizational structure and the ideological underpinnings of their functioning (Ouellette 2008: 233). Neoliberal structures reward those neoliberal citizens that internalize the ideological systems that serve these structures. Inversing older patriarchal ideas about ideal workers, young women are produced as ideal neoliberal laborers who are flexible, self-motivated, willing to reinvent themselves for the labor market and willing to work under exploitative conditions

Ide, 3 (Hasinoff 2008: 329). Individualization and personal responsibility are indispensible aspects of neoliberal subjectivity (ibid 329) and as such, collective bargaining is out of step with this trend. Symptomatic of this shift was government response to unemployment in the 1990s. Under president Clinton, the answer to the trend toward more low-paid temporary, benefit-free blueand white collar jobs and fewer decent permanent factory jobs was to invest in education and training programs (Aronowitz and Difazzio 2010: 14). This reliance on human capital moved the responsibility of job creation away from government or private institutions, to the individual whose responsibility it was to become marketable. Training initiatives of this type reinforce the idea that the path toward economic stability is individual, with workers needing to gain flexible and transferrable skills to be able to respond to a rapidly changing market. Unfortunately, structural realities of the shrinking job market meant that such initiatives lead nowhere for many who bought the promise (Aronowitz and Difazzio 2010: 14). For these workers, the psychological neoliberal impulse would be selfblame, seen as a failure of individual effort to get ahead in a highly competitive job market which provided a knowledge economy for elite workers, a service economy for unskilled labor and a lack of job security for everyone (Gonick 2006: 6; Sender 2006: 135). In this formulation, the worker herself is commodified, and the subject-commodity is responsible for their market value. Both institutions and individual workers must become responsible and accountable under market-driven reforms. Accountability in this neoliberal formulation springs from a highly competitive market in which workers must quantify and justify their work as productive. This is more difficult in service and knowledge industries than in material production. Increasing attention and energy must be siphoned justifying the value of ones work

Ide, 4 and to oversight, made possible through increasingly formalized hierarchical structures. In secondary education, we see this occurring through programs such as No Child Left Behind, where holistic educational processes must give way to test scores that can quantify each teachers and schools value, which then impacts the teachers salary and the schools funding. In higher education, this competitive accountability has led to an academic culture that values publication over teaching and breeds a culture of narcissism (Heery 2009: 250). The internalization of neoliberal assumptions indicates that the corporate managerial class, which has consolidated power in many spheres of social life, has achieved ideological hegemony determining the common sense of civil society (Aronowitz and Difazzio 2010: 45). CLASS FORMATIONS Similarly to discussions of other identities, conceptualizations of class are most helpful when situated in the intersection of the structural and the subjective. The macrolevel architecture of social class takes shape within the symbolic understandings of individual actors (Stuber 2006: 343). Whereas structural class springs directly from societys economic organization of inequalities, individuals imbue these inequalities with meaning in constructing their class identities (ibid 286). For those interested in democratic social change, therefore, the microsituational encounters among classed, gendered, and racialized subjects must be understood as ground zero for all social action for the micro situation is where class comes to exist (Yodanis 2006: 343). This subjectivity can only be constructed, however, from positions within social relations and structures (Skeggs 2002: 12). As Marx put it, Men [sic] make their own history, but not just as they please The legacy of the dead generations weighs like an alp upon the brains of the living. Whereas the debate between the degree of analytic weight to give to

Ide, 5 individual agency or structural forces has been central to sociology, for an understanding of class formation and a push for emancipatory academic worker organizing, it is more helpful to describe the dialectical relationship between these two spheres than to quantify influence. As such, organizing around structural change is insufficient without addressing and confronting ideological underpinnings (which directly impact identity formation) of such policies. As neither structures nor ideologies are static, class can be seen as a process always changing and in formation (Bettie 2003: 193). The fluidity and historically composed nature of class identity is central to any project aiming at influencing class relations, for as class categories must be constantly reproduced in practice there is a moment of possibility for social change (ibid 55, 193). Those activists and academics interested in social change, then, are given opportunities in which changing class structures give way to ideological and subjective ruptures. As normalized social relations are reproduced through everyday social interaction and practice (Ray and Qayum 2009: 4), the microlevel field of discourse is a clear battle ground of ideas. These insights point to the fact that, against structuralist or economic-determinist viewpoints, changes in economic structure do not seamlessly lead to class consciousness without the ideological intervention of those ready to advocate for a reformulation of class subjectivity as enacted and performed daily on the micro level (Skeggs 2002: 6). Bourdieus framework for understanding class lies in the movements and transferrals of specific types of capital in ways that generate individual and community power. The flows of capitals in this way connect the structural and ideological elements by which social and economic power are procured and assured as a communitys habitus (external practices and internal senses of boundaries and/or possibilities) is imbued with specific forms of cultural and social capital (Ortner 1998: 13). Whereas educational attainment is understood as harbinger of

Ide, 6 cultural capital, this form of capital can only generate social power, and subsequently economic capital, through social legitimating or transference via symbolic capital (Skeggs 2002: 8). Symbolic capital legitimates other forms of capital and therefore make them transferrable into economic benefit or increases in social status, but this conversion can become blocked by structural power and ideological discourses (ibid 11). Such blockages delegitimize cultural capital, limiting its social power. Even if such capital still holds significance for the individual, it cannot be traded as an asset (ibid 10). Class positions are closely related to the degree by which cultural capital is legitimated and therefore able to generate economic and social benefit. While the cultural capital of the middle classes can offer substantial rewards in the labor market (ibid 10), delegitimized capital ceases to promise such rewards. As economic structures change, such rewards can be made null. SHIFTING CLASS IN THE [NEOLIBERAL] UNIVERSITY Throughout the post World War II period (1945-1975), universities in the United States played a central role in shaping the class-character of the United States, both structurally and ideologically. Neoliberal ideology (relying on post-class, post feminist and post-race discourse) are the contemporary manifestations of class relations forged expanding industry and global military, economic, and diplomatic influence related protecting US interests in the Cold War. As the state subsidized students through the GI Bill (college enrollment doubled between 1945 and 1950 (Aronowitz and Difazzio 2010: 41)) and Cold War research and development (the university-military-industrial complex (Ciafone 2005: 5)), universities became training grounds for new generations of members of the professional managerial class and Cold Warriors (Ciafone 2005: 5). Walkerdine and Ringrose described this as the end of the working class through the embourgeoisement of the population (2006: 3).

Ide, 7 The security of this new middle class and the ideological fight against Communism led to the invisibility of class as a concept (Skeggs 2002: 7). The new middle class were not the maligned bosses of the Marxist imagination, but rather professionals within the government and corporate bureaucracies which also doubled in the immediate post-war period. Ideologically, this new designation so hegemonically permeated American ideology that even labor leaders today characterize all Americans as middle class with the exception of those at the extreme socioeconomic ends of poverty or opulence. This new class dynamic formed the material basisfor the American ideology of exceptionalism, and particularly, the belief in mobility which would take central importance in the rise of neoliberal ideology (Aronowitz and Difazzio 2010: 41). While many of these professional workers were still exploited, intergenerational living standards rose for this class of mainly white, male workers. Academic prestige and higher levels of autonomy allowed the US worldview to trumpet Weberian statusbased arguments over class analysis. Today, however, downward pressure has caused many service industry and academic jobs to increasingly resemble working class jobs with high alienation, strict managerial oversight and standardization, and an immiseration of wages, stability and benefits. The postwar US economic boom remained subject to periodic busts and recessions highlighting the instability of the globalizing economy. The university system of the 1950s was subject to massive cuts during the financial crisis of the 1970s, setting the scene for the neoliberal university with state appropriations dropping so heavily that if the 1977 level had been maintained, higher education would be receiving an additional $13 billion above current existing support (Ciafone 2005: 5). Accelerating in the 1980s, we have been witness to a sweeping set of economically-driven changes steadily transforming academic institutions around the world (Castree and Sparke

Ide, 8 2000: 222). Economic changes have a direct bearing on class relations as class is never just a stagnant category but a dynamic reflection of societys relation to the labor process (Aronowitz and Difazzio 2010: 273). Social inequality has dramatically increased, leading many in the government and media to talk about the disappearing of the middle class related to deindustrialization. The public funding of university systems, which made the new middle class possible has increasingly eroded, leading to increased corporate pressures on the university systems to remodel themselves according to capitalist ideology, with increased emphasis on efficiency, product development, idea production, and accountability. Corporate managers have come to see universities as increasing sites of profit-producing enterprises. According to Castree and Sparke: Businessmen are flocking to education, bringing with them a flood of dollars. They say they will turn the $700 billion education sector into the next healthcare that is, transform large portions of a fragmented, cottage industry of independent, nonprofit institutions into a consolidated, professionally managed, money-making set of businesses that include all levels of education (2000: 225). Privatization in the neoliberal university has intensified hierarchy, giving increased power to managers/ administrators (Slaughter and Rhodes 2000: 73) who rely more heavily on part-time instructors and graduate students (Dowling 2008: 814); while increasing proportional funding to male-dominated technoscienceknowledge economies that benefit corporate competitiveness such as market-oriented product development (Slaughter and Rhodes 2000: 73). Universities, along with other public institutions, have turned to corporations for financial support, creating university-industry partnerships which are vehicles for transferring public wealth to the private sector (ibid 73). This reliance on private capital has changed the social context of public education in a way that corporate efficiency is fighting to replace the concept of public good. According to Bettie, this envisioning of education, serving capital and other

Ide, 9 systems of domination is incompatible with the role education should play in a democracy, including expanding democracy and preparing citizens who can envision a different economic and social order (Bettie 2003: 203). The corporatized university has impacted not only the public mission of education but also academic workers themselves, as academic work has been transformed by strong central management and accountability initiatives. WORKING FOR THE NEOLIBERAL UNIVERSITY Graduate assistants working in todays universities are both exploited (Moser 2001) and increasingly alienated both from other workers through competition for funding (Castree et al. 2006: 762) and from their work through accountability initiatives through which teaching and research must be quantifiable and ranked according to measures of productivity (Castree et al. 2006: 761, 763) as a consumer product and not as a learning process. Injections of market capital into research further alienates researchers from their work as research is directed less by autonomous and curious, morally-charged scientists or by long-term social significance, but more because it is assessed as potentially profitable (Castree et al. 2006: 763). In relation to gender equality in higher education employment, this trend creates a paradox. Although women comprise numeric majorities of students at the undergraduate and graduate levels, monies are being moved away from fields with relatively large proportions of women (Slaughter and Rhodes 2000: 73) to fuel market-based research. While full-time faculty and workers in marketfriendly disciplines are transformed under neoliberalism into managed professionals (ibid), universities are increasingly exploiting more flexible labor of low-paid academic professionals in a move that has been described as the proletarianization of academic work (Aronowitz and Difazzio 2010). The growing trend according to Richard Moser, Associate Secretary of the American Association of University Professors, includes a growing proportion of people

Ide, 10 working and teaching in higher education today [that] hold low income jobs without benefits, security, respect or the resources they need to do the job well (2001: 5). Structural changes impacting many academic workers are related to a devaluing of cultural capital related to broad education and knowledge fields that are not easily transferred into corporate profits, such as much of the arts, humanities, and social sciences. As such, realigning class relations are not consistent through the academic institutions. Even within these fields, ascendant subfields of music business, advertising, and human relations serve as institutional attempts of unprofitable disciplines to compete with the technoscience fields of knowledge for corporate patrons. Relatedly, teaching itself has been devalued in relation to profit-driven research. Such devaluation carries the lesson that teaching and learning[and] the pursuit of the truth, are all unworthy activities held in low regard by society and by the university community itself (Moser 2001: 7). This low regard speaks directly to the relative worth of certain kinds of cultural capital within the American university, and bears directly on the working conditions and future prospects of many academic workers. Clifford Geertz notes that graduate students refer to themselves as the pre-unemployed (Moser 2001: 6). This cynical outlook is reflected in Freemans assessment of graduate employment as transient temp jobs for the new education industry (2000: 251). While university administrators attempting to block graduate assistant union drives have argued that graduate assistants are apprentices, Freeman asserts that this argument rests on assumptions of faculty mentorship of graduate employees and graduate employees futures as tenured faculty (2000: 251). These arguments are strained by the erosion of tenure. Not only are there fewer tenured faculty, with increased workloads, to serve as mentors to graduate assistants, but assurance of tenure-track academic work for new PhDs is decreased (Freeman 2000: 253). As

Ide, 11 the number of full-time positions have stagnated (Slaughter and Rhodes 2000: 73), faculty are slowly transformed into part-time employees (Moser 2001: 3). My current experiences as a graduate employee have strengthened my belief in the accuracy of critiques aimed at neoliberal subjectivity. My cohort is socialized to think of ourselves foremost as future faculty. This is achieved by encouraging graduate student interactions with tenured faculty and considerable social distance between graduate students and part-time instructors. Tenure is understood as the benchmark of success, with competitive pushes for us to develop our marketability as central to the academic trade. While unstated directly, the working assumption is that those who are not tenure track have failed despite academic restructuring under which more PhDs are awarded and the job market for tenured faculty has shrunk considerably. Percentages of part-time faculty hires growing four times more than full time hires and non-tenure track hiring rates increasing while tenure-track faculty positions have receded by 12% (Moser 2001: 4). Describing this trend to current Masters and PhD students in my department is often received with surprise, denial, or the response that indicates their assumption that they are among the exceptional, who will have little trouble finding a tenure-track job. This has been especially surprising to me as many of these discussions have taken place between myself and other sociologists, who otherwise regularly rely on such social statistics to validate arguments. Their disbelief indicates to me an internalization of the highly competitive and individualized neoliberal citizen which is incompatible with collective bargaining. For those of us interested in graduate employee organizing, then, workplace issue agitation can only go so far. In tandem with this education and agitation, ideological work must be central to union organizing, recruiting, and retaining members committed to union strategies for building collective power.

Ide, 12 GRADUATE WORKER UNIONS AS CHANGE AGENTS: A STRATEGIC AGENDA The starting point of the [labor] revitalization narrative is the fact that unions confront a neoliberal order (Heery 2009: 250). Economic structures and realities form the basis of class formations, class-consciousness, and class-based activism. The increased inequality in US society, the erosion of well-paid permanent jobs (both within the universities and in society at large), and the changing demands on academic workers present a time for unionizing within the universities (Castree and Sparke 2000: 228). This prognosis seems to be playing out among graduate employees, with 15 of the 23 currently recognized graduate assistant unions having been organized since 1990. Neoliberal reforms have also been seen as a catalyst for militant, collective action among organized graduate assistants (Heery 2009: 249). The field of struggle for building this union power is within the micropolitical sphere of discourses, recognizing that ideology is always materialized in practice[and] it organizes action (Bettie 2003: 54). Such discourses serve as competing ways of giving meaning to the world (ibid) and must be employed to highlight the structural realities of the majority of academic work, that work which has been proletarianized through downward pressure on graduate employees, non-tenure and part-time faculty members. This bread and butter work of unions, will fail, however, without directly attacking neoliberal subjectivity and the notion of the new middle class itself. Although many objectively working class people reject the term (Ortner 1998: 7), increased inequality and neoliberalism give unions an opportunity to revive the working class identity as a counter-hegemonic discourse, as class becomes an increasingly salient concept in a period where government and media analysts are decrying increased inequality as the death of the middle class .

Ide, 13 The new middle class in the United States grew out of economic and university policy of the post World War II era. The crumbling of this system and the implementation of neoliberal policies that replicate capitalist relations within academic institutions provides a central shift which can be exploited to undermine this hegemonic identity. This middle class has been seen as simply all those Americans who have signed up for the American dream in the worth of the individual (Ortner 1998: 8). As such, the rejection of this identity must be a central project to countering neoliberalism which not only has proletarianized academic workers but has also delegitimized education except as it produces goods and human capital to be consumed by corporate benefactors of public education (Castree and Sparke 2000: 228). Through discourse, social agents construct public meaning systems which are both the basis and the object of real social practice as well as the material for identity formation (Bettie 2003: 54; Ortner 1998: 10). I argue that forming a new working class subjectivity should be central to academic union organizing, focusing on creating and reinforcing the new working class. The conceptualization of the working class has been rightly criticized for being coded as white, male, heterosexual, and blue-collar. According to Bettie, If we refuse to essentialize class and instead focus on class as a formationthen the changing demographics of labor must betaken into account (2003: 197). This changing demographic must relate to gender, race, sexuality, and differential cultural forms, including occupational cultures that were once seen as middle class in order to reflect the nature of todays exploited work force. In todays economy, we can no longer imagine industrial laborers as a synechdoche for the working class. This project is complicated by real and perceived power relations between academic workers and other working class people, and must be tempered by struggles that seek to advance

Ide, 14 broad class interests. Among the social sciences, the subjectivist turn, feminist research paradigms, liberatory pedagogy, participatory action and democratic research could serve as practical bases from which to approach this work. For many of the academic proletariat, however, we must realize that our human capital and cultural capital (both inherited and gained through academic socialization) could place us as outsiders among others who share our economic class positioning. Central to the concept of habitus is the idea that we inherit ways of understanding (Skeggs 2002: 9). In the project of building a new working class subjectivity among academic workers, therefore, the experiences, habitus, and social ties to working class communities among those of us from working class backgrounds must be reformulated as a movement asset to building class power in neoliberal America. The identity of the neoliberal subject is incompatible with collective struggle, yet identities are produced via discursive frameworks and institutional forces and constraints (Bettie 2003: 54). Historically, the American university has been central to the ideological construction of class identities indicating that academic workers are well positioned socially advocate for a reformulation of class subjectivity. This work must reflect the realities of current economic structures under which many workers both within and outside of academia are subject to increasingly alienating jobs, when we have jobs at all. This structure has provided an opportunity for academic workers to build workplace power as well as solidarity with other working class people in a pluralistic yet collectivist reformulation of the new working class. The constant reproduction of these systems of inequality indicate that they are weakest when most in flux, when there are clear ruptures between systematic realities and the ideologies that uphold them. Each economic contraction (like the one we are currently facing) provides a unique opportunity for a new world to be born if we, the workers, are prepared to deliver it.

Ide, 15 References Aronowitz, Stanley and William Difazzio. 2010. Jobless Future. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. Bettie, Julie. 2003. Women Without Class: Girls, Race, and Identity. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Castree, Noel and Matthew Sparke. 2000. Professional Geography and the Corporatization of the University: Experiences, Evaluations, and Engagements. Antipode 32(3): 222-229. Castree, Noel et al. 2006. Research Assessment and the Production of Geographical Knowledge. Progress in Human Geography 30(6): 747-782. Ciafone, Amanda. 2005. Endowing the Neoliberal University. Work & Culture 7: 1-26. Dowling, Robyn. 2008. Geographies of Identity: Labouring in the Neoliberal University. Progress in Human Geography. 32(6): 812-820. Freeman, Amy. 2000. The spaces of Graduate Student Labor: The Times for a New Union. Antipode 32(3): 245-259. Gonick, Marnina. 2006. Between Girl Power and Reviving Ophelia: Constituting the Neoliberal Girl Subject. Feminist Formations 18(2): 1-23. Hasinoff, Amy. 2008. Fashioning Race for the Free Market on Americas Next Top Model. Critical Studies In Media Communication 25(3): 324-343. Heery, Edmund. 2009. Labor Divided, Labor Defeated. Work and Occupations 36: 247-256. Moser, Richard. 2001. AAUP: The New Academic Labor System. American Association of University Professors. Retrieved December 1, 2010 (http://www.aaup.org/AAUP/issues/contingent/moserlabor.htm?PF=1)

Ide, 16 Ouellette, Laurie. 2008. Take Responsibility for Yourself: Judge Judy and the Neoliberal Citizen. Pp. 231-250 in Reality TV: Remaking Television Culture, edited by Susan Murray and Laurie Ouellette. New York: New York University Press. Ortner, Sherry B. 1998. The Hidden Life of Class. Journal of Anthropological Research 54(1): 1-17. Ray, Raka and Seemin Qayum. 2009. Cultures of Servitude. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Sender, Katherine. 2006. Queens for a Day: Queer Eye for the Straight Guy and the NeoLiberal Citizen. Critical Studies in Media Communication 23(2): 131-151. Skeggs, Beverley. 2002. Formations of Class & Gender. London: SAGE Publications. Slaughter, Sheila and Gary Rhodes. 2000. The Neoliberal University. New Labor Forum. 6: 73. Stuber, Jenny M. Talk of Class: The Discursive Repertories of White Working- and UpperMiddle-Class College Students. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 35: 285-318. Walkerdine, Valerie and Jessica Ringrose. 2006. Feminities: Reclassifying Upward Mobility and the Neo-liberal Subject. Pp. 31-46 in The SAGE Handbook of Gender and Education, edited by Christine Skelton, Becky Francis, and Linda Smulyan. London: SAGE Publications Yodanis, Carrie. 2006. A Place in Town: Doing Class in a Coffee Shop. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 35: 341-366

You might also like

- SSU TuitionpresentDocument9 pagesSSU TuitionpresentMichael IdeNo ratings yet

- Durkheim and Social Movements: Secular Religions in The "Abnormal" Development of The Division of LaborDocument8 pagesDurkheim and Social Movements: Secular Religions in The "Abnormal" Development of The Division of LaborMichael IdeNo ratings yet

- Weber and Social Movements EnkuDocument9 pagesWeber and Social Movements EnkuMichael IdeNo ratings yet

- Organizing Graduate Employees The New Taking Root in The OldDocument31 pagesOrganizing Graduate Employees The New Taking Root in The OldMichael IdeNo ratings yet

- Marx and Social MovementsDocument8 pagesMarx and Social MovementsMichael Ide100% (1)

- Conceptual Difficulties and Promises of Interaction Ritual Chains TheoryDocument10 pagesConceptual Difficulties and Promises of Interaction Ritual Chains TheoryMichael IdeNo ratings yet

- Gramsci Weber Social Movements, Enku IdeDocument21 pagesGramsci Weber Social Movements, Enku IdeMichael IdeNo ratings yet

- Taco Bell Study Enku IdeDocument28 pagesTaco Bell Study Enku IdeMichael IdeNo ratings yet

- Obrien and Diverse Neoliberalism Enku IdeDocument10 pagesObrien and Diverse Neoliberalism Enku IdeMichael IdeNo ratings yet

- The Formation of An Organized Working ClassDocument30 pagesThe Formation of An Organized Working ClassMichael IdeNo ratings yet

- Terrorizing The VulnerableDocument3 pagesTerrorizing The VulnerableMichael IdeNo ratings yet

- Enku Ide Sweatshop History For USASDocument2 pagesEnku Ide Sweatshop History For USASMichael IdeNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Grossberg, Lawrence - Strategies of Marxist Cultural Interpretation - 1997Document40 pagesGrossberg, Lawrence - Strategies of Marxist Cultural Interpretation - 1997jessenigNo ratings yet

- Chicana Artist: Cecilia C. Alvarez - Yasmin SantisDocument10 pagesChicana Artist: Cecilia C. Alvarez - Yasmin Santisysantis100% (3)

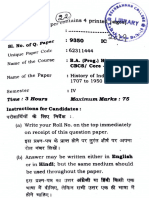

- B.A (Prog) History 4th Semester 2019Document22 pagesB.A (Prog) History 4th Semester 2019lakshyadeep2232004No ratings yet

- Sociology ProjectDocument20 pagesSociology ProjectBhanupratap Singh Shekhawat0% (1)

- League of Minnesota Cities - Data Practices - Analyze Classify RespondDocument84 pagesLeague of Minnesota Cities - Data Practices - Analyze Classify RespondghostgripNo ratings yet

- Palmares 2021 Tanganyka-1Document38 pagesPalmares 2021 Tanganyka-1RichardNo ratings yet

- Spain PH Visas 2014Document1 pageSpain PH Visas 2014Eightch PeasNo ratings yet

- List of Projects (UP NEC)Document1 pageList of Projects (UP NEC)Bryan PajaritoNo ratings yet

- Legal BasisDocument3 pagesLegal BasisMaydafe Cherryl Carlos67% (6)

- Lens AssignmentDocument14 pagesLens Assignmentraunak chawlaNo ratings yet

- Women: Changemakers of New India New Challenges, New MeasuresDocument39 pagesWomen: Changemakers of New India New Challenges, New MeasuresMohaideen SubaireNo ratings yet

- 13 - Wwii 1937-1945Document34 pages13 - Wwii 1937-1945airfix1999100% (1)

- Registration Form For Admission To Pre KGDocument3 pagesRegistration Form For Admission To Pre KGM AdnanNo ratings yet

- Cebu Provincial Candidates for Governor, Vice-Governor and Sangguniang Panlalawigan MembersDocument76 pagesCebu Provincial Candidates for Governor, Vice-Governor and Sangguniang Panlalawigan MembersGinner Havel Sanaani Cañeda100% (1)

- DM B8 Team 8 FDR - 4-19-04 Email From Shaeffer Re Positive Force Exercise (Paperclipped W POGO Email and Press Reports - Fair Use)Document11 pagesDM B8 Team 8 FDR - 4-19-04 Email From Shaeffer Re Positive Force Exercise (Paperclipped W POGO Email and Press Reports - Fair Use)9/11 Document ArchiveNo ratings yet

- Pidato Bahasa InggrisDocument2 pagesPidato Bahasa Inggrisiffa halimatusNo ratings yet

- Literary Theory & Practice: Topic: FeminismDocument19 pagesLiterary Theory & Practice: Topic: Feminismatiq ur rehmanNo ratings yet

- Loads 30 Jun 21Document954 pagesLoads 30 Jun 21Hamza AsifNo ratings yet

- Economic Reforms - MeijiDocument7 pagesEconomic Reforms - Meijisourabh singhalNo ratings yet

- Philippine Collegian Tomo 90 Issue 19Document12 pagesPhilippine Collegian Tomo 90 Issue 19Philippine CollegianNo ratings yet

- The Forum Gazette Vol. 4 No. 20 November 1-15, 1989Document12 pagesThe Forum Gazette Vol. 4 No. 20 November 1-15, 1989SikhDigitalLibraryNo ratings yet

- 1 QQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQDocument8 pages1 QQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQJeremy TatskiNo ratings yet

- Montebon vs. Commission On Elections, 551 SCRA 50Document4 pagesMontebon vs. Commission On Elections, 551 SCRA 50Liz LorenzoNo ratings yet

- In The Middle of EverythingDocument6 pagesIn The Middle of EverythingPEREZ SANCHEZ LUNA KAMILANo ratings yet

- The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGS) Play BookDocument2 pagesThe Sustainable Development Goals (SDGS) Play Bookterese akpemNo ratings yet

- Bayero University Kano: Faculty of Management Science Course Code: Pad3315Document10 pagesBayero University Kano: Faculty of Management Science Course Code: Pad3315adam idrisNo ratings yet

- Law Commission Report No. 183 - A Continuum On The General Clauses Act, 1897 With Special Reference To The Admissibility and Codification of External Aids To Interpretation of Statutes, 2002Document41 pagesLaw Commission Report No. 183 - A Continuum On The General Clauses Act, 1897 With Special Reference To The Admissibility and Codification of External Aids To Interpretation of Statutes, 2002Latest Laws Team0% (1)

- dhML4HRSEei8FQ6TnIKJEA C1-Assessment-WorkbookDocument207 pagesdhML4HRSEei8FQ6TnIKJEA C1-Assessment-WorkbookThalia RamirezNo ratings yet

- Monitoring The Monitor. A Critique To Krashen's Five HypothesisDocument4 pagesMonitoring The Monitor. A Critique To Krashen's Five HypothesisgpdaniNo ratings yet

- Migrant Voices SpeechDocument2 pagesMigrant Voices SpeechAmanda LeNo ratings yet