Professional Documents

Culture Documents

SCIR Issue III

Uploaded by

Samir KumarCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

SCIR Issue III

Uploaded by

Samir KumarCopyright:

Available Formats

SoU1uiv C.iiiovi.

I1iv.1io.i Riviiw

Volume 2, Number 1 - Spring 2012

Te Southern California International Review (SCIR) is a bi-annual interdis-

ciplinary print and online journal of scholarship in the eld of international

studies generously funded by the School of International Relations at the

University of Southern California (USC). In particular, SCIR would like

to thank the Robert L. Friedheim Fund and the USC SIR Alumni Fund.

Founded in 2011, the journal seeks to foster and enhance discussion between

theoretical and policy-oriented research regarding signicant global issues.

SCIR also serves as an opportunity for undergraduate students at USC to

publish their work. SCIR is managed completely by students and also pro-

vides undergraduates valuable experience in the elds of editing and graphic

design.

Copyright 2012 Southern California International Review.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any

form without the express written consent of the Southern California International

Review.

Views expressed in this journal are solely those of the authors themselves and do not necessarily

represent those of the editorial board, faculty advisors, or the University of Southern California.

SoU1uiv C.iiiovi. I1iv.1io.i Riviiw

scinternationalreview.org

Sta

Editor-in-Chief

Angad Singh

Assistant Editors-in-Chief:

Samir Kumar and Landry Doyle

Editors:

Rashmi Rikhy

Chandni Raja

Taline Gettas

Cover Design and Layout: Samir Kumar

Dedicated to the memory of a beloved teacher and respected leader:

Robert L. Friedheim

Professor of International Relations, 1976-2001

Director of the School of International Relations, 1992-1993

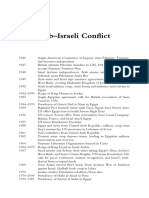

Contents

1. Shalom, Y'all

Assessing the Inuence of ird-Party Mediators on Negotiation Outcomes

Landry Doyle

9

2. e Sounds of Silence

Explanations for the Lack of Political Participation and the Ramications for

Democracy in Russia

Lara Nichols

33

3. Opportunities for Migrant Participation in Mexican Politics

Dual Citizenship, Expatriate Voting, and the Appeal of Migrant Political

Candidates

Pedro Ramirez

73

4. e World Cup and World Order

An Analysis of Soccer as a Tool for Diplomacy

Nancy Talamantes

89

A letter from the editor:

It is with great pleasure that I introduce the third issue of the new Southern California

International Review (SCIR). is bi-annual undergraduate journal based at the University

of Southern California seeks to create a unique opportunity for students to publish their

research and other academic work in order to spread their ideas to a wider audience. By fos-

tering such dialogue between students of international relations and other related elds both

on campus and throughout the region, SCIR looks to promote a better understanding of

the global issues facing our world today. As our world becomes increasingly interconnected

through technology, trade, and diplomacy, it is evident that events occurring anywhere on

the globe have worldwide eects. e need to study international relations has never been

more important and thus this journal desires to contribute unique and innovative ideas to

this fascinating and essential eld of study.

In particular, I am happy to announce that this is the rst issue in which SCIR accepted

article submissions from students at universities other than USC.

e pieces contained in the journal are written by undergraduate students and were

chosen by our six member editorial board. e graphics, templates, and formatting were

also done by our editorial board. In an eort to not restrict students in their submissions,

SCIR welcomed submissions on a wide variety of topics in the realm of international studies

thereby emphasizing our commitment to interdisciplinary learning. SCIR is also available

on-line at www.scinternationalreview.org. e journal would also not be here without the

generous funding of the School of International Relations.

Lastly, SCIR would very much appreciate your feedback on this issue. Please send us

your comments, questions, and suggestions at scinternationalreview,gmail.com.

Sincerely,

Angad Singh

Editor-in-Chief

Shalom Yall

Assessing the Inuence of ird-Party Mediators on Negotiation

Outcomes (abridged)

1

Landry Doyle

Peacemaking eorts in intractable conicts rarely set high expectations for success.

e conicts prolonged, historical nature paired with its deep psychological wounds make

it nearly impossible for leaders to adopt political solutions. Given these dicult realities, the

third-party mediators who lead peacemaking eorts are rarely held responsible for the outcome

of negotiationsthe dicult circumstances are deemed to be outside of a mediators control.

Intrigued by the lack of consideration devoted to the third-party mediator, this study raises the

question of whether a mediator could in fact have a signicant inuence on the outcome of an

international negotiation, and if so, what factors could make some mediators more successful

than others in leading disputing parties to reach an agreement. Using comparative analysis,

this study oers an answer by evaluating the dierences between the Egyptian-Israeli nego-

tiations in 1978-9 and the Syrian-Israeli negotiations in 2000. ese two cases demonstrate

signicant similarities, and yet one reached an agreement while the other ended in failure.

While systemic, domestic, and individual analyses each attempt to explain the cases dier-

ing outcomes without considering the role of the mediator, these explanations are not entirely

convincing. By examining the inuence of third-party mediators, three relevant conclusions

emerge:

1. A mediator who pursues a directive strategy, and has the power to enact it, is more likely

to reach an agreement than one who resorts to merely facilitative tactics.

2. A mediator who prioritizes the peace process over other national security concerns is more

likely to reach an agreement than one who does not deem the agreement to be essential to the

national interest.

3. A mediator who utilizes team members with signicant decision-making authority will be

more likely to reach an agreement than one who does not.

ese three conclusions suggest that a third-party mediator can have a signicant inuence

on the outcomes of a negotiationone that can rival, and at times supersede, systemic, domes-

tic, or individual conditions.

1 Due to length constrictions, a literature review and a section on existing explanations were entirely removed from this dra;

the section on research methods and case selection was signicantly altered. e full dra is available online at www.scinterna-

tionalreview.org.

L D is a senior at the University of Southern California double-ma-

joring in International Relations and Spanish.

10

S C I R - Vol. 2 No. 1

Landry Doyle

Peace has one thing in common with its enemy,

with the end it battles, with war

Peace is active, not passive;

Peace is doing, not waiting;

Peace is aggressiveattacking;

Peace plans its strategy and encircles the enemy;

Peace marshals its forces and storms the gates;

Peace gathers its weapons and pierces the defense;

Peace, like war, is waged.

I. Introduction

On the week of January 3, 2000, the citizens of Shepherdstown, Pennsylvania decorated

store windows with the same peace propaganda posters used twenty years earlier to cel-

ebrate the signing of the Israeli-Egyptian peace treaty. In 1979, Egypt became the rst state

to establish bilateral peace with Israel, and in 2000, as Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak

and Syrian Foreign Minister Farouk al-Sharaa traveled to Shepherdstown to engage in an

unprecedented level of negotiations, the international community could not resist the urge

to hope for a similar outcome. e 1978 Camp David Summit led to the Egyptian-Israeli

peace treaty and was the yardstick" against which all other mediation eorts would be mea-

sured. Shepherdstown shared a particularly eerie resemblance" with Camp David, and as

the New York Times reported, comparing and contrasting the two was inevitable, because

parallels [were] so explicit."

2

Nonetheless as spectators evaluated the many similarities and

dierences between the two cases-the historical context, the issues to be negotiated, the

prospect of success-there seemed to be one factor that escaped public scrutiny-the iden-

tity of the mediator himself. It is possible the role of the mediator was disregarded as being

insignicant in comparison to the factors surrounding the negotiating parties or that the

mediators -Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton-were viewed to be so similar that a comparison

was not deemed to be of merit.

Unfortunately the Shepherdstown negotiations, and the Geneva summit which fol-

lowed it, failed to achieve an agreement between Syria and Israel, and, in attempt to interpret

the event's failure, comparisons to the Camp David Summit resurfaced. Again, dierences

between the negotiating parties-their leaders, their domestic politics, and their position

within the international system-dominated the discourse. Each of these explanations has

merit, yet none is fully convincing. Intrigued by the lack of consideration devoted to the

2 Deborah Sontag, You Need Good Glasses; Looking for Camp David on the Map of Shepherdstown," New York Times, Janu-

ary 9, 2000.

11

S C I R - Vol. 2 No. 1

Shalom Yall

third-party mediator, this study raises the question of whether this variable could have a

signicant inuence on the outcome of an international negotiation, and if so, what factors

could make some mediators more successful than others in leading disputing parties to

reach an agreement.

II. Research Methods and Selection of Cases

is is a comparative case study that utilizes a method of dierence framework. To suc-

ceed in this eort, two cases must be selected that are similar in many respects but neverthe-

less have diering outcomes. e strength of a comparative study is entirely dependent on

case selection; cases must have convincingly signicant similarities. Although no two cases

are identical, the negotiations between Israel and Egypt, mediated by US President Jimmy

Carter in 1978-79, and the negotiations between Israel and Syria, mediated by US President

Bill Clinton in 2000, oer a remarkably strong comparison. is study does not intend to

provide a complete account of all events surrounding either of the cases, but rather to simply

consider and weigh the systemic, domestic, and individual level factors that may have con-

tributed to the negotiations' outcome.

3

Case One: Camp David Negotiations 1978-1979

While there is no way to briey summarize a history between two nations that have

been tenuous neighbors for thousands of years, this study is generally concerned with the

period following the Six-Day War ending June 10, 1967, aer which Israel took control of the

Sinai Peninsula. In response to the Six-Day War, the United Nations Security Council issued

Resolution 242, which remains the primary international statement on the Arab-Israeli con-

ict. Resolution 242 calls on Arab states to recognize Israel's right to existence, while requir-

ing Israel to withdraw from territories acquired through war.

4

Since the UN rst articulated

this territory for peace" solution, it proved to be a challenging concept. However, Egypt was

the rst state to adopt its precepts, albeit warily. Egypt was adamant about recovering its lost

land, and aer a disappointing performance in the 1973 Yom Kippur War that exposed its

insucient military capabilities, it nally seemed willing to give the land for peace" strategy

a chance. Under the guidance of US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger's shuttle diplomacy,"

Egypt and Israel signed the Sinai II agreement in 1973, in which both states pledged to use

diplomatic means to resolve the conict with Israel. While this major development seemed

to suggest that the two states were well on their way to full peace, it was also evident that both

parties had drastically dierent views on what a peace could look like. Additionally, deep

distrust between the parties prevented them from negotiating directly, and throughout the

3 e comparison of systemic and domestic factors is not provided in the abridged version of this work.

4 e full text to U.N. Resolution 242 is available in William B. Quandt's, Camp David: Peacemaking and Politics (Washington,

DC: e Brookings Institution, 1986), 341-2.

12

S C I R - Vol. 2 No. 1

Landry Doyle

period the United States established itself as the only mediating party with the relationships

and the leverage to advance Arab-Israeli relations.

3

Although the US put the Middle East on hold during the 1976 election, the new Carter

Administration was eager to return to the cause. e Carter Administration rst sought to

achieve a comprehensive peace that would address all of the signicant outstanding issues

in the region. Intending to draw from the successful 1973 Geneva conference, Carter tried

to establish another multilateral Geneva conference, in which all major players in the region

would negotiate alongside the United States and the Soviet Union. is strategic framework

collapsed as almost all parties disagreed over the general principles of a potential solution,

the appropriate process of negotiations, and the participation of a Palestinian delegation.

Just as prospects for improvement seemed dim, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat made

a surprising and unprecedented move by volunteering to travel to Jerusalem and speak di-

rectly with the Israeli Knesset. Sadat was the rst Arab leader to ocially visit Israel, and

although his speech articulated his longstanding position, the visit broke down signicant

psychological barriers between the two nations. About a month aer Sadat's visit to Israel,

Begin traveled to Ismailiya, Egypt to engage in direct negotiations with Sadat. In their rst

attempt at direct negotiation, the two heads of state le with drastically diering accounts

of the outcomes. According to the Israelis, Sadat was on the verge of accepting Israeli pro-

posals, and if it hadn't been for his hard-line advisers, would have done so. Sadat however

claims to have le the meetings feeling disillusioned by Begin's ridiculous position." At one

point when Begin suggested maintaining settlements in the Sinai Peninsula, Sadat actually

thought it was a joke. Overall the Egyptians le believing that the Israelis were still unpre-

pared to accept Egyptian sovereignty over the Sinai.

6

On January 3, 1978, Israel began work

on four new settlements in the Sinai, which angered Egyptians and Americans, who both

thought Israel had committed to freezing settlements.

While direct relations between Sadat and Begin seemed to hit an impasse, the Carter

Administration became more active in communicating with each side, working to under-

stand each side's proposals and trying to draw concessions to create a foundation for future

agreement. On June 30, 1978, Carter was ready for bolder action and issued letters to Begin

and Sadat inviting them to a formal summit. e Camp David Summit became a thirteen-

day negotiation, held from September 3, 1978 to September 17, 1978. President Carter and

his team mediated the negotiations, which were largely secluded from any media presence.

While the mediations were trilateral, Begin and Sadat only met directly on the rst and

nal days of the summit. e main issues of contention were Israel's settlements, oilelds,

and military bases remaining in the Sinai Peninsula and the question of linkage," or to

3 Ibid., 3.

6 William B. Quandt, Peace Process: American Diplomacy and the Arab-Israeli Conict since 1967 (Berkeley: University of

California Press, 2001), 193; Jimmy Carter, White House Diary (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2010), 169.

13

S C I R - Vol. 2 No. 1

Shalom Yall

what degree a Palestinian solution should accompany a bilateral Egyptian-Israeli peace

agreement. Carter's team shaped both of the resulting agreements: A Framework for the

Conclusion of a Peace Treaty between Egypt and Israel," and A Framework for Peace in the

Middle East."

In the months following Camp David, each party confronted political problems, and

rather than quickly concluding the negotiations by signing a formal treaty, the process

reached an impasse. By the end of 1978, prospects for peace seemed dim.

7

Carter reentered

the negotiations, ramped up US nancial and military assistance to each state, and conceded

loose linkage by allowing a weak and ambiguous statement on Palestinian peace. Eventually

a formal Egyptian-Israeli agreement was signed on March 26, 1979, guaranteeing the full

return and demilitarization of the Sinai Peninsula and the normalization of relations be-

tween Israel and Egypt. irty years later the agreement remains unviolated.

8

Case Two: Shepherdstown and Geneva Negotiations 1999-2000

e history of issues on the Syrian-Israeli border are remarkably similar to those of

the Egyptian-Israeli border. Much like the Sinai Peninsula, the Israelis invaded Syria's

Golan Heights during the Six-Day war in 1967 and have ruled over the territory ever since.

Although the Syrians tried to retake the land during the Yom Kippur War in 1973, they were

ultimately unsuccessful and instead signed a disengagement agreement, forged by Henry

Kissinger, agreeing to a ceasere that continues to be enforced today. Under the auspices of

UN Resolution 242, the Syrians believe the Golan territory is rightfully theirs, and they have

refused to establish peaceful relations with Israel until every last inch of it is returned. Led

by Prime Minister Hafez al-Asad, Syria criticized Egypt's land for peace" deal with Israel

in 1978 and saw Sadat's move as a betrayal of the Arab world. As Syria held strongly to its

commitment to Pan-Arab nationalism, prospects of involving Asad in the peace process

seemed dim throughout the 1980s. However, the 1990s opened a new chapter of hope on

the Syrian front. Aer Saddam Hussein's forces invaded Kuwait in 1990, Syria joined the

US-led UN coalition in the Persian Gulf War and aerwards agreed to participate in the

1991 Madrid Conference. Despite Syria's advance towards peace, the Israelis, led by Prime

Minister Yitzhak Shamir, were only interested in peace for peace" agreements, refusing

to give up the territory Syria clearly sought. However, when Labor-party reformer Yitzhak

Rabin took oce in 1992, peace on the Syrian front nally seemed attainable. Rabin un-

derstood that peace with Syria would require full withdraw from the Golan Heights and

7 Quandt, Camp, 222.

8 Admittedly, the relationship between Egypt and Israel remains a cold peace," yet the terms of the treaty have been upheld

even as Egypt undergoes democratic transition. In September of 2011, protestors in Cairo invaded the Israeli embassy, leading

many to question the stability of the Israeli-Egyptian relationship; however, no signicant damage was done and Egyptian leader-

ship expressed its continued commitment to maintaining peace with Israel.

14

S C I R - Vol. 2 No. 1

Landry Doyle

pledged to withdraw fully from the Golan Heights provided Israel's [security] needs were

met and provided Syria's agreement was not contingent on any other agreement-such as

an agreement between the Palestinians and the Israelis."

9

is pledge became known as the

Rabin deposit," as it was a condential commitment made to US negotiators to be presented

to Syrian leadership. Although Secretary of State Warren Christopher communicated the

oer to the Syrians, little was done to prioritize movement on the Syrian track. Instead, at-

tention went to the Palestinians who were simultaneously negotiating the Oslo Accords to

be signed in 1993. Shortly aer Oslo, a peace agreement with Jordan was signed in October

of 1994.

During this period Secretary Christopher continued to meet with Rabin to discuss the

Syrian track. On July 18, 1994, Rabin reconrmed his previous commitment and specied it

further to meet Asad's demands. According to the long-held Syrian position, full withdraw

required a withdraw to the June 4, 1967 line-the line that divided Israeli and Syrian forces

on the eve of the Six-Day War. According to Ross and Christopher's accounts of their meet-

ing, Rabin agreed to withdraw to the June 4th line under the condition that security needs

were met.

10

is major breakthrough led to an aims and principles" non-paper that began

outlining security arrangements. Although various obstacles arose during this time, forward

progress was evident. With an election approaching Rabin decided to put the Syrian track

on pause, as talk of possible concessions could be controversial to his campaign.

In November of 1993, aer speaking at a peace rally meant to promote the Oslo Accords,

Rabin was assassinated by a right-winged Israeli extremist. His death shocked the interna-

tional community and increased domestic support for Rabin's commitment to peace, giving

Shimon Peres, Rabin's successor as Prime Minister, tremendous momentum to move nego-

tiations forward. Upon entering oce Peres was unaware of the commitments Rabin had

made on the Syrian front and was surprised in particular by the promise to withdraw to the

June 4th line; nevertheless, he told President Clinton he would arm any commitments

Yitzak [had] made."

11

Peres' team made progress on the Syrian track through meetings at

the Wye River Plantation outside of Washington; however, as the third round of Wye talks

began in February of 1996, a series of terrorist attacks in Israel-four suicide bombings

in nine days-led Peres to suspend the negotiating process. e political climate in Israel

drastically changed, and in May's national election Benjamin Netanyahu, a right-wing Likud

leader, defeated Peres, ending hope of realizing Rabin's vision for peace. Netanyahu's term

le little room for progress, and while some attention was given to peace on the Palestinian

front, little was done to address Syria. In 1999 Israel elected Ehud Barak, a protg of Rabin,

9 Ross, 111.

10 Although there are various interpretations of this line, the Syrians believe it to be a line specically demarcated by UN truce

ocials.

11 Ross, 212.

13

S C I R - Vol. 2 No. 1

Shalom Yall

to replace Netanyahu. Clinton's Administration had supported Barak's campaign and was

particularly encouraged by Barak's willingness to make historic strides in the direction of

peace-especially on the Syrian front.

Aer months of preparatory talks, Syria and Israel agreed to convene intensive high-

level negotiations at Shepherdstown, West Virginia on January 3, 2000. While Barak had not

yet conrmed a commitment to the Rabin deposit, he had alluded to it and was expected

to deliver it. Hafez al-Asad, whose health was beginning to decline, did not attend the ne-

gotiations and sent Foreign Minister Farouk Shara on his behalf. Previously Asad had been

unwilling to send senior-level ocials to negotiations without preconditions, thus sending

Shara was a notable concession.

12

However, some Israelis interpreted Asad's absence as a

sign that Shepherdstown would not be the nal round of negotiations. Additionally, Israeli

domestic pressures had increased in the preceding weeks. Former Defense Minister Ariel

Sharon publically labeled the Rabin deposit as a dangerous" proposition, and Barak's own

coalition seemed weary of giving up any territory.

13

With these fears in mind, Barak pri-

vately told US Ambassador to Israel Martin Indyk in mid-December of 1999 that due to the

change in his political circumstances, he would be unable to deliver the deposit.

14

Despite

Barak's trepidation, the American team still believed Shepherdstown would produce an

agreement, or at least make large strides in that direction. Shara made several concessions

during the round to demonstrate Syria's conciliatory posture; nonetheless, Barak did not

show exibility on any territorial issues, oering nothing to the Syrian delegation. Aer

four days of negotiation, the American team put forth a proposal describing Israel's posi-

tion but used bracketed language to identify the Syrian position. e dra did not put forth

independent proposals and according to Ross, reected the reality of the Syrians agreeing

on the principles of peace and the Israelis not accepting June 4 as the border."

13

Aer tabling

the dra, the negotiations were suspended for the weekend; however, before reconvening,

the dra was leaked to the Israeli press. Arabs were immediately outraged by the degree of

concessions Syria had agreed to without being promised anything in return. Before leaving

Shepherdstown, Shara directly asked Barak if he would conrm the Rabin deposit. Barak

responded with only a dubious smile.

16

e round of talks quickly concluded, and Clinton's

team was le to clean up the disaster. Although it is unclear what Clinton communicated to

Asad in the following days, it was evident that Asad felt betrayed and exposed and was weary

12 Clayton E. Swisher, Investigating Blame: US Mediation of the Arab-Israeli Conict from 1999 to 2001" (M.A. thesis,

Georgetown University, 2003), 6910

13 Ariel Sharon, Why Should Israel Reward Syria:" New York Times, December 28, 1999, Op-ed.

14 Martin Indyk, Innocent Abroad: An Intimate Account of American Peace Diplomacy in the Middle East (New York: Simon

and Schuster, 2009), 231.

13 Ross, 339.

16 Indyk, 262-3.

16

S C I R - Vol. 2 No. 1

Landry Doyle

to continue talks. Nonetheless, the US team continued communication with both parties.

Barak encouraged Clinton to organize a meeting with Asad, and Clinton agreed, believing

that Barak would nally communicate an acceptable position.

Asad agreed, and the two met in Geneva on March 26th. Barak spoke with Clinton

on the morning of the 26th to deliver his nal position, which demonstrated concessions

but only acknowledged withdraw to a commonly agreed border" rather than fully arm-

ing the June 4th line.

17

Upon hearing the proposal, Asad immediately voiced his disin-

terest. Although the American delegation thought the proposal presented a fair solution,

Asad would not agree to territorial tradeos of any kind, and the Geneva summit ended

in failure only hours aer it began. Clinton later described his disappointment: In less

than four years, I had seen the prospects of peace between Israel and Syria dashed three

times: by terror in Israel and Peres' defeat in 1996, by the Israeli rebu of Syrian overtures

at Shepherdstown, and by Asad's preoccupations with his own mortality. Aer we parted in

Geneva, I never saw Asad again."

18

roughout his presidency a peace agreement between

Israel and Syria seemed to be within reach; however, in the end, disagreement over a few

hundred meters made the dierence between peace and continued conict. Little serious

progress has been made on the Syrian front since.

III. e Individual Mediator

In 1991, Jacob Bercovitch, a leading academic voice in conict and mediation stud-

ies established original data sets quantifying the variables that aect mediation success.

19

His study considered multi-level variables such as the characteristics of the involved par-

ties, balance of power, nature of the dispute, and the duration of the conict. In regards

to Bercovitch's variables, these two cases have several signicant similarities (although the

degree of similarity varies): the type/nature of issues in conict, the importance of the dis-

pute to each party, the relationship between the disputing parties, the international status

of the parties, the parties' acceptance of mediation and general commitment to settlement,

the degree of control over the process that parties and the mediator have, the expediency of

the mediation process, the environmental context of mediation, the expected likelihood of

reaching a satisfactory outcome, and the rank of the mediator.

e nal variable Bercovitch identies is the mediator's identity, skill, and strategy,

which he argues can be the most crucial variable aecting mediation outcomes."

20

is

study will argue that this variable does reveal the primary dierence between these two

17 Quandt, Peace Process, 363.

18 Bill Clinton, My Life (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004), 903.

19 Jacob Bercovitch, Jacob, J. eodore Anagnoson, and Donnette L. Wille, Some Conceptual Issues and Empirical Trends in

the Study of Successful Mediation in International Relations," Journal of Peace Research 28, no. 1 (1991): 16.

20 Jacob Bercovitch, Understanding Mediation's Role in Preventive Diplomacy," Negotiation Journal (July 1996): 234.

17

S C I R - Vol. 2 No. 1

Shalom Yall

cases. Although mediators are oen ignored, their strategic role, and the way in which it is

utilized, does seem to account for the enduring shortcomings of the previous three expla-

nations.

21

Ironically, a comparison between these two particular mediators, Jimmy Carter

and Bill Clinton, is oen overlooked because the two men have so many similarities. Both

were in the same position of authority as presidents of the United States, and both were

Democrats, Southerners, and optimists marked by their wit and sense of humor. Apart from

their similar authority and personal histories, both Carter and Clinton had unique personal

commitments to the Middle East-developing positive relationships with leaders, gaining

popularity amongst citizens (although Carter more so with the Arabs and Clinton more so

with the Israelis), and demonstrating impressive understanding of the region's complex his-

tory and current conditions. In addition, both mediators entered the process in uniquely

ripe" times for negotiation, where all parties had notable benets to be gained.

22

Finally,

despite the region being entrenched with controversy, both Carter and Clinton displayed

considerable impartiality. Although specic members of Clinton's team may have been less

impartial, Clinton himself was greeted with praise in both Gaza and Jerusalem, demonstrat-

ing his ability to empathize with both sides. Despite these signicant similarities, a critical

analysis comparing these two mediators yields three signicant dierences that may hold

causal inuence on the negotiation's outcome:

Mediation Strategy-the extent to which the mediator played an active or passive role

in the negotiations.

Mediator's Prioritization of the Negotiations-whether the mediator saw the negotia-

tion to be a priority to his administration and of importance to advancing the national

interest

Mediator's Use of Negotiating Team-the extent to which the mediator utilized team

members eectively and maintained the group's cohesion.

Assessing each of these dierences requires comprehensive analysis, considering mul-

tiple perspectives and interpretations. is qualitative study proposes signicant, but by no

means binding, evaluations suggesting that, while some variables may possess greater in-

uence, each contributed to the mediator's eectiveness and ultimately to the negotiation's

outcome.

21 Due to length constraints, these existing explanations were not provided in the abridged version of this thesis.

22 While scholars debate how ripeness" should be determined or dened, previous sections of this paper demonstrate the

benets to be gained through agreement for each of the negotiating parties. us, while this claim is indeed debatable, this study

does not seek to further substantiate it. For further explanation see Asaf Siniver, Power, Impartiality, and Timing: ree Hypoth-

eses on ird Party Mediation in the Middle East," Political Studies 34 (2006): 806-26, although this article does not include

discussion of the Syrian case.

18

S C I R - Vol. 2 No. 1

Landry Doyle

IV. Variable One: Mediation Strategy

e rst relevant dierence between the third party mediators in these two cases is

their mediation strategy. While Carter chose to directly shape the negotiations as an active,

or directive mediator, Clinton allowed the negotiating parties to shape the process and slid

into a more passive, facilitative role. As Zartman and Touval's study suggests, a more active

mediator is more likely to succeed, especially if he is in a powerful position that provides

the resources to enforce his proposals. As Bercovtich concludes, Mediation strategies that

can prod the adversaries, and strategies that allow mediators to introduce new issues, sug-

gest new ways of seeing the dispute, or alter the motivational structure of the parties, are

more positively associated with successful outcomes than any other type of intervention."

23

1. Carter succeeds as a directive facilitator intending to shape the negotiation process

and outcome

1.1 Carters problem-solving style preferred detail-oriented, comprehensive prepara-

tion

First, President Carter's background, interests, and political style bolstered his ability

to engage directly in the negotiation process. Carter had a general inclination to be directly

involved in any issue he deemed to be of importance. At times he developed a reputation as

a micromanager, but his habitual attention to detail served him well as a mediator. With a

background in engineering, rather than politics, Carter was trained to understand complex-

ity, planning, and comprehensive design. is ability to comprehend intricate relationships

gave him a strong edge as a tactical bargainer.

24

Overall, Carter was a problem-solver at

heart, and he would not be deterred by a dicult situation. In fact some in his administra-

tion suggest that he was actually most compelled to tackle challenging issues that no one

else had been able to solve.

23

In many regards Carter's personal morality colored his entire

approach to foreign policy-he was an idealist, who believed that with commitment and

creativity, problems could be solved through cooperation.

26

In addition to his commitment

to detailed problem-solving, Carter also thrived in smaller groups, much like the setting

encountered at Camp David. Carter was not a skilled orator and oen fell at on the public

stage, but in smaller groups he was able to build trust through personal interaction.

27

23 Bercovitch, Anagnoson, and Wille, 16.

24 Telhami, Power, 179.

23 Quandt, Camp, 131; Quandt, Peace Process, 177.

26 Telhami, Power, 179-80.

27 Quandt, Camp, 31.

19

S C I R - Vol. 2 No. 1

Shalom Yall

1.2 Carter proactively initiates a risky summit negotiation

Second, Carter was proactive in taking a risk to initiate a summit negotiation, although

the prospects for success seemed dim. Initially, Carter wanted to pursue a multilateral strat-

egy to address comprehensive peace in the Middle East that even included the Soviet Union;

however, when his strategy for a meeting in Geneva fell apart, he chose to boldly change

course. Aer Begin and Sadat's tragic failure at Ismailia, Sadat publically rejected continuing

the negotiations. In response, Carter recognized that a more active and forceful" approach

was necessary and decided that the only solution, as dismal and unpleasant as the prospect

seemed," was to bring Sadat and Begin together for an extensive negotiating session.

28

He

recalls:

We [understood] the political pitfalls involved, but the situation [was] getting

into an extreme state...is decision would prove to be a turning point in our eort to

remove the only serious military threat to Israel's existence, and to provide a blueprint

for peace in the Middle East. At the time, prospects for progress were dismal...I

was fairly condent that Sadat would cooperate with me, but I had no idea how Begin

would react to my invitation."

29

Carter's only certainty was that Begin and Sadat would get nowhere on their own. e

two men's previous attempts at direct negotiation were fruitless, and their personal incom-

patibilities prevented them from compromise. However aer making the decision to con-

vene the summit, the Administration still had to decide what issues would be addressed and

what form the negotiating process would take.

Given the initially low prospects of success, Carter's advisers tended to be cautious in

setting goals and prepared to rationalize failure.

30

Although Carter recognized the impor-

tance of minimizing expectations, he was more interested in pursuing substantive ideas. By

garnering international attention and support from the world's political and religious lead-

ers, he tried to impress on Sadat and Begin the importance of entering the negotiations with

a willingness to make concessions.

31

Finally, once beginning negotiations Carter shaped the

process by determining when leaders would meet, when proposals would be issued, who

would be consulted before issuing proposals and also by emphasizing the benets of peace

and the risks of failure.

32

Few envisioned reaching an ocial agreement and suggested that

the summit instead end in a more general agreement on principles. However, Carter was

28 Carter, White, 168; Carter, Keeping, 323.

29 Carter, White, 210.

30 Carter, Keeping, 328.

31 Ibid., 324.

32 Quandt, Camp, 218.

20

S C I R - Vol. 2 No. 1

Landry Doyle

determined to work out the details and personally assume the risk that accompanied such

an individual level eort.

1.3 Carter places no time constraints on negotiation and devotes his full attention

ird, in addition to the risk associated with convening a summit, Carter assumed

an additional risk by placing no time constraints on the process and by devoting two full

weeks to the negotiations. roughout his presidency Carter demonstrated an unrivaled

commitment to the Middle East peace process, but almost nothing illustrates this fact more

than the sheer time devoted to the Camp David Summit itself. irteen days secluded from

the press, other domestic and international issues, and vital presidential responsibilities,

Carter adamantly refused to put time limits on the negotiations in order to demonstrate his

commitment to reaching an agreement. While the depth of his focus undoubtedly diverted

attention from other important issues, Carter recognized that this is oen the only way

to reach success in the Middle East as the highly personalized political-culture requires a

strong degree of direct negotiation between leaders.

33

1.4 Carter develops a profound understanding of both negotiating parties

Fourth, Carter was active in acquiring a personal understanding of both Begin and

Sadat. e two men diered drastically in both personality and negotiation strategy, thus

his extensive eorts to reconcile the two further demonstrates his commitment to directing

both parties to make concessions. Although Carter had developed a strong rapport with

both Begin and Sadat before the summit, his team provided psychological brieng books

that addressed how each leader could be expected to negotiate. e primary dierence be-

tween Begin and Sadat was how they acted under pressure. While Sadat tended to generalize

about proposals and over-arching goals, Begin paid close attention to semantics and would

haggle over the meaning of individual words.

34

Carter committed to studying how best to

accommodate and communicate with each leader, and he was adept in responding to each of

these strategies as his inner-engineer could navigate intricacies for Begin, while his idealism

reassured Sadat's insistence on the broader picture. When Sadat threatened to leave Camp

David without concluding negotiations, Carter used his strong relationship and strategic

understanding of Sadat's interests to convince him to stay. Carter writes:

Vance walked in with his face white, saying that Sadat had decided to withdraw com-

pletely from the negotiations and leave Camp David. Sadat had abruptly decided that

33 Kenneth W. Stein and Samuel W. Lewis, Mediation in the Middle East," in Managing Global Chaos: Sources of and Re-

sponses to International Conict, ed. Chester A. Crocker, Fen Osler Hampson, and Pamela Aall (Washington, DC: United States

Institute of Peace, 1996), 467.

34 Carter, White, 213.

21

S C I R - Vol. 2 No. 1

Shalom Yall

our discussions would never yield an acceptable agreement and asked for a helicopter

to take him to the airport in Washington. is was one of the worst moments of my

life, I went to my bedroom, knelt down, and prayed, and-for some reason-decided

to change from my sports shirt and jeans to a suit and tie. I went immediately to

see Sadat...I explained to him the serious consequences of his breaking o the negotia-

tions: it would damage severely the relationship between the United States and Egypt

and between him and me; he would violate his word of honor to me-the basis on which

Sadat and Begin had been invited to Camp David...I told him he had to stick with me...

He was shaken by what I said, because I have never been more serious in my life.

33

Carter understood that Sadat valued their close friendship and hoped it would increase

the partnership between Egypt and the United States. By emphasizing the long-term conse-

quences ending the summit would have on this relationship both personally and politically,

Carter was able to seize Sadat's greatest fear and leverage it to save the negotiating process.

1.5 Carter sees himself as an active negotiator

Fih, Carter himself dened his role as a mediator and active negotiator."

36

Initially,

Sadat encouraged the Americans to be a full partner" in the negotiations in order to actively

create independent proposals; the Israelis, however, preferred the US to take on a more sym-

bolic role as a bridge builder between the two parties. In response to these opposing views,

Carter did describe his role as a full partner," but on the condition that he would not try

to impose the will of the United States on others," but instead search for common ground

on which agreements [could] be reached."

37

us, Carter chose to maintain his role as a

mediator, but chose an active strategy that did advance independent proposals. In fact, the

Israelis oen accused the American team of being too active in the negotiations, especially

when Carter took the Egyptian position towards the Sinai settlements.

38

Additionally, given

Sadat's disdain for details and trust in Carter, Sadat essentially gave the American President

the authority and exibility to negotiate on Egypt's behalf.

39

us, Carter actively wielded

his inuence as the leader of the United States to encourage concessions from both sides. As

William Quandt recognizes, Power is at the core of negotiations," and Carter was skilled in

blending pressures and incentives to arrive at a nal agreement.

40

33 Ibid., 237.

36 Carter, Keeping, 331.

37 Brzezinski, 234.

38 Telhami, Power, 130.

39 Carter, White, 300.

40 Quandt, Camp, 336.

22

S C I R - Vol. 2 No. 1

Landry Doyle

1.6 Carter advances a bold American position

Sixth, in addition to advancing bold and fair American proposals, Carter was person-

ally responsible for draing the Sinai agreement. Before beginning the summit, there was

much discussion of whether the US would advance its own proposals, and many in Carter's

Administration advocated only advancing American ideas if it [was] necessary to over-

come obstacles."

41

However, Carter seemed to be interested in constructing a solution from

the onset. Soon aer taking oce he wrote that his Middle East strategy was to, put as much

pressure as [he could] on the dierent parties to accept the solution that [the US thought

was] fair."

42

Additionally, once constructing the process for the summit, Carter was clear

that, while he would consult transparently with both sides, the American team reserved the

right and had the duty" to introduce a position of compromise.

43

Aer directly shaping the

negotiating technique that would require both sides to negotiate from a single-text, Carter

and his team would dra proposals and discuss them with each side separately.

44

e most

impressive aspect of this technique is the extreme amount of personal involvement Carter

had in developing these dras. While the American team collectively wrote twenty-three

dras of the Framework for Peace in the Middle East," Carter handled the Sinai proposal,

which required eight dras, on his own.

43

is strategy proved imperative to the success of

the summit. For both Egypt and Israel, it was much easier to accept American proposals,

rather than making concessions directly to each other.

46

Direct negotiations played a very

small role in the Camp David Accords, which not only gave Carter and his team an enor-

mous responsibility, but also a crucial power to shape both the process and substance of the

agreement.

1.7 Carter sees the agreement through to its completion

Finally, aer concluding the summit, Cater continued to be active in following the

agreement until its completion as an ocial peace treaty. is proved to be more dicult

than originally expected as Begin reneged on previous commitments, especially in regards

to the language on Palestinian autonomy. Nonetheless, Carter was willing to intercede di-

rectly as the process seemed to hit a stalemate. He traveled to both Egypt and Israel and

introduced new statements, including guarantees of US military aid and nancial assistance

41 Brieng Book for President Carter at Camp David, August 1978," September 17, 1978, http://www.brookings.edu/press/

Books/peace_process.aspx, 4.

42 Carter, White, 44.

43 Ibid., 217.

44 Carter, Keeping, 406.

43 Carter, Keeping, 331; Quandt, Camp, 232.

46 Quandt, Camp, 238; Cyrus Vance, Hard Choices: Critical Years in Americas Foreign Policy (New York: Simon and Schuster,

1983), 173.

23

S C I R - Vol. 2 No. 1

Shalom Yall

as well as commitments to act if the agreements were violated in the future.

47

Carter main-

tained an active role for nearly eighteen months of negotiation until an agreement was -

nally signed on March 26, 1979.

Although the demands of the presidency could have limited Carter's role, his interest

in detailed problem-solving, his willingness to convene and devote tremendous time and

energy to a risky summit negotiation, his profound understanding of both Begin and Sadat,

and his leadership in advancing proposals demonstrate his active role as the architect of

the Camp David Accords. As Brzezinski describes, is was indeed [Carter's] success. He

was the one that gave it the impetus, the extra eort, and the sense of direction."

48

William

Quandt echoes these conclusions:

Carter played the role of drasman, strategist, therapist, friend, adversary, and media-

tor. He deserved much of the credit for the success, and he bore the blame for some

of the shortcomings. He had acted both as a statesman, in pressing for the historic

agreement, and as a politician, in settling for the attainable and thinking at times of

short-term gains rather than long-term consequences. In many ways the thirteen days

at Camp David showed Carter at his best. He was sincere in his desire for peace in the

Middle East, and he was prepared to work long hours to reach that goal. His optimism

and belief in the good qualities of both Sadat and Begin were reections of a deep faith

that kept him going against long odds. His mastery of detail was oen impressive. And

he was stubborn. He did not want to fail."

49

1. Clinton slides into a more communicative role and refuses bold, shaping action

1.1 Clintons problem-solving style is centered on his superb political abilities

First, Clinton's personal and political style hindered his negotiation strategy. In many

ways Clinton shared the optimism and belief in cooperative negotiating that were integral

to Carter's success. He also shared Carter's personal interest in the Middle East peacemak-

ing, which he demonstrated by being the rst President to travel to Gaza, and the rst since

Nixon to visit President Asad in Damascus. However despite shared interest and optimism,

two traits separate Clinton from Carter. First, Clinton was much more of a politician. Many

consider Clinton to be one of the greatest political minds of a generation," winning seven

out of eight elections and serving twenty-one years in public oce.

30

President Clinton

47 Carter, White, 299.

48 Brzezinski, 270-1.

49 Quandt, Camp, 237-8.

30 Joe Lockhart, Press Secretary to President Clinton, interviewed by Clayton E. Swisher, Investigating," 303. Carter contrast-

ingly served only twelve years in public oce, winning four out of six elections, winning reelection only once as State Senator.

24

S C I R - Vol. 2 No. 1

Landry Doyle

understood the domestic political situations the negotiating parties had to deal with. In par-

ticular, Clinton exerted tremendous eort and resources to get Barak elected, even sending

his own political strategists Robert Shurm, Stanley Greenberg, and James Carville to aid in

the campaign.

31

Clinton was uniquely tied to Barak's domestic political situation. Clinton the

politician also had the ability to reach across barriers and appeal to both sides in a conict;

however, this also caused him to portray positions as more exible than they really were,"

hoping that he would be able to charm his way past the details.

32

e second important dierence between the two US Presidents is Clinton's intellectual

approach to problem solving. Clinton's knack for politics was aided by his incredible intel-

ligence, and multiple sta members describe Clinton's mind as a sponge" with a tremen-

dous capacity to quickly absorb detailed information.

33

Although he shared Carter's ability

to comprehend detail, he did not micromanage like Carter nor emphasize highly complex,

structured problem solving.

34

Rather, Clinton was a macro-level persuasion artist who used

his ability to understand detail only as it benetted his overarching vision. Some argue that

Clinton may have become over-reliant on his intellectual ability and political savvy by failing

to prepare adequately. While Carter refers to months of studying, William Quandt equates

Clinton's approach to preparation as pulling an all-nighter."

33

While Clinton did have an

incredible ability to hear both sides and empathize with each of them, Clinton was not one

to get involved with substance. As Quandt notes:

ose who knew Clinton best would frequently argue that his strengths and weak-

nesses were inseparable. He was intelligent, but not focused; personable, but not loyal;

politically skillful, but deeply self-centered; exible, but without a solid core of convic-

tion...He had a deep need for recognition and success; was inclined toward compromise

rather than principled stands; and was skillful with words and relationships to build

broad coalitions of support for himself and his policies."

36

Clinton preferred to be a politician with a talent for getting opposing sides to talk to

each other. Both Barak and Asad considered him to be trustworthy and committed to the

31 Indyk, 263.

32 Quandt, Peace Process, 379.

33 Ross, 631; Maria Echaveste, Deputy Chief of Sta to President Clinton, interviewed by Clayton E. Swisher, Investigating,"

227.

34 Samuel Lewis, former US Ambassador to Israel, interviewed by Clayton E. Swisher, Investigating," 426.

33 Swisher, Investigating," 178.

36 Quandt, Peace Process, 379.

23

S C I R - Vol. 2 No. 1

Shalom Yall

process, but seeing everything from a political lens may have hindered his ability to objec-

tively push for a solution.

37

1.2 Clinton articulates a passive approach to the peace process throughout his term

Second, in addition to Clinton's political mindset and improvised approach to problem

solving, his Administration was hesitant to lead the Middle East peace process in general.

e Clinton Administration lived by the motto, we cannot want peace more than the par-

ties do."

38

is articulates a passive approach that refuses to take the reins. Obviously this

does not mean that Clinton did not want to play an important role in the peace process,

indeed his record shows that his administration was involved in the Middle East peace

process throughout his presidency; however, it does suggest that his posture was purely

responsive to the wills of the negotiating parties. Clinton's record in the region substanti-

ates this claim: he played almost no role in developing the Oslo Accords, the Wye River

Memorandum was never implemented, the Syrian-track negotiations failed, and the 2000

Camp David Summit also failed. is is not to suggest that the issues were easy to address,

but for as much involvement as Clinton had, it is notable that in the end, he had little to show

for his eorts, especially at the height of US' international prestige when the most leverage

was available to shape the process and outcomes.

1.3 Clinton does not prepare adequately for Shepherdstown and does not give the

summit his full attention

ird, the Clinton Administration's general hesitancy to direct the peace process was

specically evident during the Shepherdstown negotiations, as the process lacked strategic

preparation. First, members of Clinton's administration admit a general lack of structure,

even calling the process loosy-goosy."

39

Others echo a general sense of mismanagement and

insucient preparation, and Clinton himself referred to his role as merely dragging a com-

promise over the nish line."

60

Clinton's disillusioned conception of what would be required

was also evident in his time commitment to Shepherdstown. Unlike Carter at Camp David,

Clinton traveled back and forth between the negotiations and his other business at the White

House. is either projects a sense of distraction or suggests that the Clinton Administration

did not view Shepherdstown as a decisive round of mediation-either of which would have

been detrimental to the impression Clinton's team needed to make. Additionally, Clinton

37 Ross, 140; Joe Lockhart, interviewed by Clayton E. Swisher, Investigating," 302.

38 Quandt, Peace Process, 380.

39 Toni Verstandig, former Deputy Assistant Secretary for Near Eastern Aairs, interviewed by Clayton E. Swisher, Investi-

gating," 243-247.

60 Edward P. Djerejian, Danger and Opportunity: An American Ambassadors Journey rough the Middle East (New York:

reshold Editions, 2008), 167; Branch, 607.

26

S C I R - Vol. 2 No. 1

Landry Doyle

knew how important his authority would be in mediating between these parties, as nei-

ther responded well to other members of Clinton's team. Barak believed that all negotiating

should be done at the Head of State level and had a history of calling the White House de-

manding to speak directly with Clinton.

61

Similarly, Syrian Foreign Minister Farouk Shara

put up hard-line positions when dealing with Ross or Albright, and then became more exi-

ble once meeting with Clinton. However as Ross admits, with Clinton constantly leaving and

returning, it was dicult to keep the most exible positions on the table.

62

While Clinton's

sta worried that the President was being over-used, past experience with the Middle East

should have illustrated the Head of State's critical role as the ultimate authoritative gure in

a highly-personalized political culture.

1.4 Clinton assumes a role as a passive facilitator at Shepherdstown

In addition to an ill-planned negotiation process at Shepherdstown, Clinton restricted

his negotiation strategy by assuming a facilitative role. Rather than adopting Carter's direc-

tive, shaping strategy, Clinton preferred to merely educate the negotiating parties on con-

cessions that were needed. He pointed towards a solution instead of forcing either side to

accept a position.

63

In addition, the Carter team focused the negotiations on the central trade

o to be made-land for peace-while Ross admits that President Clinton's style" was not

suited to enforcing a basic tradeo.

64

Yet this allowed Clinton to avoid taking a position on

central issues in the negotiation. He considered everything to be negotiable rather than set-

ting clear terms for agreement. Both the Syrian and Israeli negotiating teams agree that the

United States failed to capitalize on major opportunities. As Israeli political scientist Zeev

Maoz observes, e fact that the Clinton administration refrained from playing a more

assertive role at crucial junctures of negotiation may have been as decisive a factor for the

failure to reach an agreement as any error, hesitation, or misperception on the side of the

Israeli and Syrian decision makers."

63

In addition, during the process Secretary Albright was

aware of the directive leadership the negotiating parties expected from President Clinton.

As she recalls:

I asked both Shara and Barak privately if they seriously believed an agreement would

be reached. ey each said yes, which I found encouraging until I probed for the reason.

61 Madeleine Albright, interviewed by Clayton E. Swisher, Investigating," 383.

62 Ross, 331-2.

63 Ibid., 639.

64 Ibid., 420.

63 Zeev Maoz, Syria and Israel: From the Brink of Peace to the Brink of War," Cambridge Review of International Aairs 12,

no. 1 (1998): 266-67.

27

S C I R - Vol. 2 No. 1

Shalom Yall

ey each believed that in the end President Clinton would intervene to force conces-

sions upon the other."

66

Clearly both parties expected Clinton to play a more directive role. Even Martin Indyk,

one of Clinton's leading advocates for the Syria rst-track, admits, It should not have been

beyond the capabilities of American diplomacy to bridge the gap...It remains puzzling why

[Clinton] didn't try harder."

67

1.5 Clinton allows Barak to assume a directive role

Not only did Clinton shy from directing the negotiations, he worsened the situation by

allowing Ehud Barak to maintain control throughout the process. First, it was Barak who

initiated the summit. Clinton clearly says, Ehud Barak had pressed me hard to hold these

talks early in the year."

68

Rather than controlling the timeline of negotiations based on US'

preparedness or Syrian domestic concerns, Barak's wishes were paramount to all other con-

cerns. While surely the negotiating parties and their willingness to participate is important,

this directly contrasts the 1978 case where the Carter Administration initiated the process

to respond to a stalemate.

Aer agreeing to Barak's call to begin talks, Barak continued to dominate the process

and substance at Shepherdstown. Ross recalls the rst time Shara and Barak met at Blair

House to appear before the press. Ross recommended that only Clinton make a statement

in order to prevent either side from making a comment that might express rigid thinking.

However, as Ross recalls, Barak had other ideas" and suggested that each leader make a

statement.

69

As Ross foresaw, Shara's statement appealed to the traditional Syrian base and

was highly critical of Israel. Obviously Shara was to blame for his discouraging comments,

but Clinton also deserved blame for allowing Barak to divert from the plan. Aer negotia-

tions began, Barak set the pace, and was noticeably stalling to prevent progress.

70

Yet Clinton

continued to be conciliatory and was unwilling to force Barak outside of his comfort level.

71

Clinton acute awareness of Barak's political situation encouraged the US to be overly respon-

sive to Israel's internal political dynamics, causing them to shi gears" on both substance

and strategy at Barak's request.

72

Ned Walker, a former US Ambassador to Israel and the

Assistant Secretary for Near East Aair reiterated Barak's control:

66 Albright, 479.

67 Indyk, 287.

68 Clinton, 883.

69 Ross, 340.

70 Albright, 478.

71 Swisher, Investigating," 97.

72 Toni Verstandig, interviewed by Clayton E. Swisher, Investigating," 131.

28

S C I R - Vol. 2 No. 1

Landry Doyle

Nobody was telling Barak what to do. President Clinton was fully supportive of

Barak. I don't think if anybody had stood up and said 'this doesn't make sense,' that

anybody would have listened! Barak was just...he was in the driver's seat throughout

this thing."

73

It's likely that Clinton believed his personal relationship with Barak and skilled politi-

cal persuasion would convince Barak to nalize an agreement at Shepherdstown; however,

Clinton was unable to persuade Israel's leader to commit. Secretary Albright explains that

Clinton sincerely trusted Barak's commitment to peace and was reluctant to substitute his

judgment for an Israeli Prime Minister who was so determined to make history"

74

Ross re-

iterates this dilemma:

We let Barak dictate too much of what was going to be possible and what we would

do. We could have taken a tougher posture towards him in terms of just making it clear

we wouldn't do certain things. e problem is that, here was a guy who was prepared

to make very far-reaching concessions and they were, aer all, his concessions. ey

weren't our concessions."

73

While it's understandable for Clinton to trust Barak's judgment, a directive approach

would have introduced other means to change Barak's mind that would not have hindered

the US' commitment to Israel. Possibilities could have included increasing weapons sys-

tems, withdrawing campaign commitments, or threatening to walk away from mediation.

Additionally, Clinton was an incredibly popular gure in Israel during this time, more so

than Barak, and initiating a personal campaign for an agreement may have had a signicant

impact on Israeli public opinion.

76

Overall, Clinton only facilitated the negotiation process

at Shepherdstown and instead allowed Barak to lead. is strategy allowed both parties to

escape without making any substantial commitments and furthermore, compromised the

trust of the Syrian negotiating team. ey entered the process with the understanding that

the Rabin deposit would nally be put on the table and instead were le empty-handed and

disappointed. As Clinton laments, If we had known of Barak's retreat in advance...we could

have prepared the Syrians. As it was, we had misled them."

77

While Clinton acknowledges

Syrian disappointment, and even hints at his own responsibility for it, he fails to recognize

how a change in strategy could have helped prevent it.

73 Ned Walker, interviewed by Clayton E. Swisher, Investigating," 133.

74 Albright, 484.

73 Dennis Ross, interviewed by Clayton E. Swisher, Investigating," 210.

76 Indyk, 283.

77 Branch, 381.

29

S C I R - Vol. 2 No. 1

Shalom Yall

1.6 Clinton never puts forth an independent American proposal

Sixth, Clinton's dra treaty failed to put forth independent ideas or use language that

moved the substance of negotiations forward. In Carter's Camp David negotiations, a sin-

gle-negotiating text was used to direct the process and substance while putting forth an

American position. Clinton's dra treaty did not serve the same purpose. Although Ross

told Clinton to present the dra as the American judgment of what agreement could be

possible, the dra was entirely silent on any Israeli concessions to be made.

78

e dra

only referred to a commonly agreed border," failing to commit Israel to the Rabin deposit.

e Syrian team called the June 4, 1967 line the ignition" to starting negotiations, and

the American dra intentionally refrained from including it.

79

In addition to concealing

Israeli concessions, the dra included all the concessions Syria had proposed, many of which

were substantial signs of progress.

80

Although Ross encouraged Clinton to sell this dra to

the best of his ability, Ross admits that the ideas never presented the best judgment of the

American team:

Agreements are forged...on the basis of reconciling the fundamentals each must have

to preserve its identity, dignity, and political base. e Clinton ideas presented on

December 23, 2000, did that between Israelis and Palestinians-at least in our best

judgment. We never did the same on the Syrian track; the ideas presented on March

26, 2000, in Geneva were what Barak was prepared to have us convey to Asad...We un-

derstood it on the Syrian track but wisely never presented our best judgment the way

we did between Israelis and Palestinians. I say wisely because... the most important

American role is not putting our best judgment on the table. Our most important role

may be getting the sides to the negotiating table when the only dialogue they have is

one of violence.... Imposed decisions will not endure. No agreement forced from the

outside will ever have legitimacy."

81

Ross clearly prides his Administration on refusing to propose its own ideas, suggesting

that somehow articulating an American position would have automatically imposed" an

unacceptable solution. Yet in light of the success of Carter's single-negotiating text strategy,

this argument is hard to defend. An American dra did not have to be the be-all, end-all

to a negotiation. As Carter proved, an American position can be a starting point to objec-

tively identify central tradeos which would later be open to modications from each side.

Deputy Special Middle East Envoy Aaron David Miller also arms Ross' fear of taking

78 Ross, 338.

79 Indyk, 262.

80 Martin Indyk, interviewed by Clayton E. Swisher, Investigating," 188.

81 Ross, 772.

30

S C I R - Vol. 2 No. 1

Landry Doyle

rigid" positions, but nonetheless, agrees that not taking any positions seems to have been

a mistake.

82

e Clinton team struggled in deciding how much to put forth throughout the

Middle East peace process. Secretary Albright says they entered with the mindset that the

parties needed to work it out for themselves; however, they ultimately realized that the only

way to do it was to put down [American] parameters."

83

Unfortunately, on the Syrian-track

this never happened.

1.7 Clinton understands Syrias bottom line, but never forces Barak to meet it

Seventh, aer failure at Shepherdstown, the Clinton Administration continued to let

Barak drive negotiations at Geneva, while leading the Syrian delegation to believe their re-

quests would be met. First it is important to note a key dierence between the Syrian and

Israeli delegations: the Syrian team was clear about its bottom line, while the Israeli team

never articulated their nal position. With Syria, their bottom line had been clear for years-

they needed every inch of land within the June 4, 1967 line, and they had shown no exibility

on this point. Syrian Deputy Foreign Minister Walid Mouallem describes the rst time he

met Barak: I told him twenty-eight times within two hours about Israeli withdrawal to the

4th of June, 1967 line. Barak told me, 'Why are you repeating this:' I said, 'Because I want to

you to go to sleep and dream of this line.'"

84

Asad also directly told Albright, I cannot settle

for anything less...No person or child in Syria would agree to make peace with any party that

kept even one inch of our land."

83

Not only was Syria explicit in stating their position, but they were also not receptive to

even subtle alterations. When the US proposed looking at the 1923 International Boundary

instead, Asad's legal advisor warned them of presenting the idea, arguing that merely sug-

gesting it would illicit a negative reaction that could threaten the entire process.

86

For Asad,

the territory itself was not important, rather the land was a sign of dignity and honor.

87

In

addition, both Sadat in Egypt and King Hussein in Jordan had recovered all their land. Asad

was the only hold out and the last true Arab nationalist, if he agreed to a deal he needed to

be able to say 'I got the same thing the Egyptians got in the Arab world with Camp David

1978, and the Jordanians too in 1994.' He couldn't go home and say 'I got less.'"

88

Clinton had

82 Aaron David Miller, former Deputy Special Middle East Envoy, interviewed by Clayton E. Swisher, Investigating," 130.

83 Madeleine Albright, interviewed by Clayton E. Swisher, Investigating," 381.

84 Walid Mouallem, interviewed by Clayton E. Swisher, Investigating," 362.

83 Albright, 473.

86 Swisher, Investigating," 98.

87 Ross, 73.

88 Ned Walker, interviewed by Clayton E. Swisher, Investigating," 134.

31

S C I R - Vol. 2 No. 1

Shalom Yall

tested Syria's exibility on this issue, but even he concluded that creative formulations of the

Rabin pocket were not going to work-the June 4, 1967 border was the Syrian bottom line.

89

Not only did the Clinton team know Syria's bottom line, but as they approached the

Geneva negotiations, Clinton also led Asad to believe that his requests would be met.

Amongst the Clinton team there are various stories concerning what Clinton actually told

Asad when requesting the summit. However, the Syrian team convincingly contends that

Clinton assured a full withdrawal. Deputy Syrian Foreign Minister Walid Mouallem says

Clinton told Asad that Barak was ready to please," and Asad's translator describes a phone

call in which Clinton said, your requests are met; you will be very happy." Asad asked to

clarify if this specically meant the June 4th line would be delivered, and Clinton respond-

ed, I don't want to speak over the phone. But trust me: you will be happy."

90

Not only do

Syrian claims substantially suggest that Clinton directly implied the June 4th line would

be presented at Geneva, but Saudi Prince Bandar Bin Sultan also claims to have relayed

secret messages between Clinton and Asad guaranteeing the June 4th border. According

to Bandar, Clinton said he knew Asad wanted Israel to withdraw from the Golan Heights

and reinstate the 1967 border. Clinton also said he was planning to pressure Barak to satisfy

these demands; and if successful, he would initiate a summit. is was the message Bandar

communicated with Asad. Bandar's covert role is now widely acknowledged by members in

Clinton's Administration, but at the time there wasn't a clear understanding of what he was

communicating to Asad. If Bandar's accounts are accurate, Asad was under the impression

that a summit would only be convened if Barak had agreed to the June 4th line. Secretary

Albright was not informed of this arrangement until she met with Bandar weeks aer the

summit. She was angered that National Security Advisor Sandy Berger had not kept her in-

formed, at Sandy...Now I understand why Asad looked so stupid to me."

91

While Albright

and others on the American team thought Asad came to Geneva to negotiate in general,

Asad was under the impression that his bottom lines had already been met. Instead, the US

team exploited Syria's trust by promising their bottom line without securing the assurance

that Barak would deliver it.

1.8 Clinton never forced Israel to disclose its bottom line

is leads to a second critical oversight-Clinton's team never specically knew where

Barak would draw Israel's bottom line. Barak had a history of presenting his last absolute

nal oer" when he in fact was saving additional concessions for later."

92

Albright and

89 Ross, 300.

90 Walid Mouallem, interviewed by Clayton E. Swisher, Investigating," 361; Dr. Bouthaina Shabban, interviewed by Clayton

E. Swisher, Investigating," 368-9.

91 Elsa Walsh, e Prince," e New Yorker, March 24, 2003, 34-3.

92 Martin Indyk, interviewed by Clayton E. Swisher, Investigating," 201.

32

S C I R - Vol. 2 No. 1

Landry Doyle

Indyk both arm that President Clinton went to Geneva without knowing what Israel was

really willing to give up and that Barak refused to even discuss the issue.

93

In this sense,

the Administration had no end game in sight, no specic Israeli positions, and no central

tradeo to build from. While Barak did articulate a position to Clinton, Barak's own Chief

Negotiator Uri Sagi claims that he was prepared to go beyond that...He was prepared to go

all the way."

94

Barak himself may not have known what his limitations were, and in spite of

his undisputable desire for peace, he wavered in mustering the political courage to make

sacrices for it. Although Barak was too hesitant to state his absolute positions, he also did

not want to close the door on the peace process. Much like initiating Shepherdstown, Barak

prodded the Americans to arrange a meeting with Asad in Geneva. Clinton agreed, largely

as a favor to the Prime Minister he was unwilling to say no to."

93

1.9 Barak continues to direct the negotiations at Geneva, while Clinton merely facili-

tates

Clinton arrived in Geneva aware of Syrian demands and condent in his persuasive

ability but entirely dependent on Barak's willingness to table the Rabin deposit. Once again

Clinton acted as a skilled communicator and trusted leader, but not as a director-that was

Barak's position. Albright describes the extent of Barak's control and explains Clinton's will-

ingness to go along with it:

Always the micromanager, Barak produced a complete script for the President's use

with Asad. In a manner I thought was patronizing, he said it would be ne for the

President to improvise the opening generalities, but the description of Israel's needs had

to be recited word for word. President Clinton went along with this process for several

reasons. He had more hope than the rest of us that the initiative would succeed, and

certainly Barak's oer was more forthcoming than any other the Syrians were likely to