Professional Documents

Culture Documents

BVP Measuring Growth Businesses With Recurring Revenue

Uploaded by

Saumil MehtaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

BVP Measuring Growth Businesses With Recurring Revenue

Uploaded by

Saumil MehtaCopyright:

Available Formats

Measuring High-Growth, Recurring Revenue Businesses

Why conventional metrics for tracking the progress of a business are inadequate, and even misleading, for a large new class of companies that deliver technology as a service. By David Cowan

A managing partner of Bessemer Venture Partners, David Cowan has led early stage investment rounds in technology service providers such as Postini; PSI-Net; Register.com; Verisign, which he co-founded and where he served as CFO and Chairman; Keynote, Telocity, Counterpane, Netli, Qualys, Cyota, and more recently Lifelock, LinkedIn and Perimeter eSecurity. Bessemer Venture Partners has also invested in other technology service vendors such as Endeca, Eloqua, Retail Solutions, SelectMinds, Intego and Cornerstone On Demand.

Introduction In the old days before the internet, technology innovators commercialized their inventions primarily in the form of equipment or software. Microsoft, Intel, Sun, Oracle, Dell, Cisco, Seagate, Siebel, and most every other venture-backed startup of the late 20th century collected most revenue dollars soon after securing a purchase order, with only a minor portion of revenue coming from annual maintenance contracts. But today, with the mass proliferation of always-connected computing devices, an increasing number of startups seize the opportunity to deliver technology in the form of perpetually-renewable automated services that either (i) operate network-based computers for their customers to access (e.g. Vonage, Akamai, Salesforce.com), or (ii) deliver streams of datasuch as software iterations (e.g. McAfee, Websense), environmental measurements (Bloomberg, UPS package tracking), or entertainment and news media (e.g. WSJ.com, CNN/SI Fantasy Sports, XM Radio, Real Rhapsody Music Service, Tivo). Regardless of when the cash is collected for these subscription services, there is no value delivered up front, and so GAAP reasonably recognizes all their revenue ratably over time, month by month. Of course, common business metrics evolved in the old days, before this marriage of technology and subscriptions. Now, as the business model changes around them, entrepreneurs and venture capitalists continue to depend upon the conventional metrics of high-tech product companies. Unfortunately, like other bad habits, this dependency often stunts their growth. Startups with recurring revenue need different terminology and accounting metrics to paint a clear picture of their business and establish a framework for properly compensating performance, especially among the sales staff. Over the last thirteen years, while serving actively on the boards of many startups selling technology subscriptions, the author has participated in the construction of a new accounting metric that its adopters find addictive in its simplicity, clarity and utility.

********************

Bessemer Venture Partners

Confidential

Conventional Value Metrics in High Growth Technology Companies It is easy to agree that businesses are worth the net present value of expected future earnings streams. High growth companies, however, maximize that value in the short term by prioritizing market share over net income and gross margins. That is why, in explosive markets, sales growth represents the most important metric of value accretion. It is also easy to agree that technology is hard to deploy. The newest products tend to require some combination of customization, integration, testing, and training, and often this cycle depends upon the deployment of complementary products within the system. If anything goes wrong, consumers can return product or leave the channel with inventory that doesnt sell through. Enterprise customers usually have the practical abilityif not the contractual rightto reverse the purchase order, and certainly the vendor cannot know, until final product acceptance, how much sales expense it will incur until the cycle completes. To reserve against these risks, GAAP does not immediately recognize 100% of purchases as revenue. But however long the deployment cycle takes, it represents the least risky stage of the sales cycle (unless of course the product doesnt workan unsustainable problem). Once management knows how much product has been ordered, they know rather precisely how much revenue will ultimately follow. The catch-all bookings number is such a strong leading indicator of revenue that it trumps revenue itself as the most important metric of sales growth, and, consequently, value accretion in high-growth technology companies. Indeed, variable compensation in these companies most often ties to bookings, from the junior telesales rep up to the CEO. In private companies, the operational portion of board meetings tends to revolve around the plan, forecast and actual achievement of bookings goals. And in public companies, stock prices rise and fall on perceived changes in bookings long before the associated GAAP revenue is even recognized. Other sales growth metricssuch as returns and DSOstill warrant attention. And what constitutes a booking is certainly subject to debate, if not regular abuse, since FASB offers no guidance here to follow. But bookings indicate future value accretion so much more accurately than competing metrics that we find ways to navigate the swamp by establishing company-specific guidelines, and monitoring the variances between revenue and prior bookings to expose abuse and ambiguity. Break-even is the pivotal time in a companys development when booked software licenses and equipment gross margins catch up to the R&D and sales expenses. But it is a milestone with many repeat visitorsit is painfully obvious, and relevant for this discussion, that one bad bookings quarter can plunge a company deep into the red.

********************

Subscriptions: The New Business Model for Technology To appreciate the appeal of subscription-based businesses, consider how the earnings and revenue multiples of technology service vendors (TSV) dwarf those of product companies. 1 In the software sector for example, traditional software companies are trading at 2-3x trailing revenues whereas their SaaS counterparts are trading at 5-6x trailing revenues. There are good reasons why the new business model is so sexy.

To be clear, professional service companies are not TSVstheir service is neither automated nor, with rare exception, perpetually-renewable.

Bessemer Venture Partners

Confidential

From the customers perspective, subscriptions often deliver value you cant get in a box: security software that adapts to rapidly evolving threats; media streams too personalized to economically broadcast; software too complex to run in-house; networks too vast to reproduce. And they dont require an up-front commitment of capital to purchase. From the investors perspective, TSVs offer higher expectations of future earnings streams by promising far clearer visibility into future revenue, since even the fastest growing TSV has most of next quarters revenues (and the next) already contracted. A growing product company faces increasing risk as it must outperform itself quarter after quarter, but a TSV is more like an engine with a flywheel, smoothly accelerating with the gentle application of force. The most valuable TSVs dont even need to stop for fuelthey grow organically from service usage expansion within their existing accounts. (Verisign, for example, grew steadily through the turn of the decade as its existing customers registered and secured new domain names.) And since TSVs must interact with their customers regularly, they are far better positioned than product vendors to introduce entirely new offerings into the installed base. (Keynote, for example, has grown steadily by acquiring tiny TSVs with services that can be upsold to Keynotes customers.) The business model offers such compelling benefits that some conventional, offline software vendors (e.g Endeca) go so far as to sell their licenses with one year terms, simulating the subscription base of a TSV. On the downside, subscription services are harder to execute, since their customer support facility faces the constant threat of churn, and they require more capital in order to subsidize the delay in payment and the operation of a network and data center. Of course, these barriers to entry only amplify the value premium enjoyed by successful TSVs. The TSV matures very differently from a product company, incurring three types of cost: development, operating, and variable. Development costs range from minimal to high, depending upon the companys decisions to make versus buy. Operating costs are somewhat fixed (or at least very lumpy), typically funding a highly available, fault-tolerant data center, with redundant facilities, disaster recovery, and lots of network bandwidth. The operating expense line can also cover data sources, including externally supplied feeds or the maintenance of geographically dispersed sensors. Variable costs are normally lowthey may include storage and network bandwidth, but they are chiefly dominated by sales and support. With more cost and no up-front payment, TSVs travel a longer, more expensive road to profitability, but once they arrive they are unlikely to regress. For this reason, the profitability milestone plays an even more prominent role in the life of a TSV.

********************

The Mismatch Despite having the business model of a magazine publisher, management teams of TSVs need the same operational skill sets and domain knowledge as those of high-tech product companies. And so TSVs are founded by entrepreneurs, and staffed by managers, trained in the culture of bookings. Herein lies the problem. Bookings meaningfully foretell revenue in product companies, but not in TSVs. At the time of customer acquisition, it is impossible to even guess the revenue that will follow from a sale, since the contract is subject at any time to churn on the one hand and expansion of seats or services on the other. The only reliable prediction you can make from any sale is that the monthly revenue will in fact change over time. Just as problematic, the bookings number often includes renewals and upsells (which may or may not happen at time of renewal). It does not make sense to track these numbers, along with new account sales, as one metric, in part because renewal bookings are far easier to get, and so the bookings metric has to be

Bessemer Venture Partners

Confidential

decomposed into different line items. Even still, the renewal booking has to be presented in context of renewal opportunities, since an increase of 10% in bookings might simply have resulted from a 20% increase in accounts up for renewal, masking the increase in churn. As a metric of value accretion, the bookings number shows a third weakness of smaller magnitude: TSVs attract value premiums based on the visibility and stability of recurring revenues, but the inevitable presence of non-recurring revenues from professional services, training, patent licenses, and other secondary opportunities pollute the bookings number with less valuable business. And yet, sales vice-presidents accustomed to hammering away on bookings tend to see the proverbial nail, and so every purchase is somehow quantified as a booking.

********************

Why It Matters To appreciate the consequences of focusing on the wrong metric, consider the case of an actual TSV (with only minor simplifications), referred to here as Acme Systems. The reader is asked to digest a few paragraphs of detail, but with the promise of a scandalous conclusion Acme sells flat-rate annual subscription contracts to enterprises, usually for $120k or $10k per month. Acme started the year with 45 customers, and in Q1 the company successfully renewed about $1m of annual contracts, with no churn or price erosion, and added another 5 accounts. That brought Acme to about $6 million of annual recurring revenue by the end of Q1 (though the accounts came on line at the end of the quarter, so only about $1.35m of GAAP revenue had been recognized in Q1). The sales department was paid commissions for booking $1.6 million ($1m of renewal and $600k of new business). Acme still had a long way to go to reach breakeven, and so management justified the operating loss with a commitment to increase bookings in Q2 by an admirable 25% quarter-overquarter, to $2 million. Unfortunately, early in Q2, network glitches inflicted severe outages on Acmes customers, and some new competitorsincluding a large public companyswooped in. 15 Acme accounts, representing almost exactly $2 million of annual recurring revenue, were coming up for renewal in the quarter, including a couple of larger ones paying $20k per month. Dissatisfied, the two large accounts switched vendors, as did 4 others, while another 2 accounts churned away simply for internal budget reasons. The eight churned contracts didnt expire until nearly the end of Q2 (indeed, most new customers are signed up at the end of a quarter), so they continued to generate revenue through most of the quarter. Meanwhile, the competitive pressure enabled the remaining seven accounts to negotiate discounts averaging 20%, though three of the seven accounts did purchase additional services that actually increased each of their overall contracts by an average of $10k per year. The sales department obviously did not book any of the available $480k from the two large accounts, or the $720k from the other 6 churned accounts. However, the 7 renewing accounts, who had been paying $120k each, did account for renewal bookings4 of them signed an annual contract for $96k each, and 3 for $130k each, for a total booking of $720k. In addition, Acme closed 3 new deals, all with multi-year contracts (a new commission bonus had been offered for long term deals with the idea that it would reduce churn). One of them was a whoppera five year deal worth $1.78 million, including $1.36 million for 8 months of implementation services, and a discounted subscription rate of $7k per month. Closed early in the quarter, two months of consulting ($340k) and subscription ($14k) were recognizable in Q2. The other two new accounts were three year deals, each for $8k per month, but not starting until Q3. New bookings therefore totaled $2.36 million, and GAAP revenue for the quarter came in at $1.834m (thats $1.48m from pre-existing accounts plus $354k from the whopper).

Bessemer Venture Partners

Confidential

So overall, how did Acme do in Q2? Lets see what the CEO had to say in his quarterly summary

Presidents Letter to the Board of Directors Q2 was a terrific quarter for Acme Systems. We had strong bookings of $3.13 million against a plan of $2.0 million, representing 154% of plan, and a 93% increase over Q1 bookings of $1.6 million. This good news stemmed in part from a large 5 year deal for our core service, including $1.36 million of professional services. In fact Im pleased to report that overall we locked in several longer term contracts this quarter. We also renewed 7 customers this quarter, 3 of whom were upsold additional services. GAAP revenue of $1.83 million exceeded plan by 10%, and rose 35% from Q1! We did exceed the expense plan by 14%, but principally due to higher than expected sales commissions. In light of recent sales success, Management recommends that we accelerate the sales hiring plan.

The summary above is factually accurate, and seems to provide compelling evidence for the CEOs optimistic recommendation. But with the benefit of more detail from the preceding paragraphs, the reader senses that something isnt right TSVs attract such high multiples because of the recurring nature of the revenue, which doesnt increase from non-recurring revenue, multi-year contracts, or churn-ridden renewals. To accrue value, a TSV must escalate its subscription revenue, first to cover the large fixed expenses and later to increase profit. But Acme failed to do that in Q2. In fact, Acme had exited Q1 with $500,000 of monthly recurring revenue, of which it lost $40k from the two large accounts, $60k from the other 6 churned accounts, and $5.5k from the net changes to the 7 renewals. New accounts added $23k of monthly revenue, bringing the companys post-Q2 monthly recurring business to $417,500. Thats why the following summary of Q2 would have boded better for Acme.

Presidents Letter to the Board of Directors Q2 was surely Acme Systems most disappointing quarter to date, as we faced scalability challenges and increased competition. Churn and poor sales productivity reduced Acmes customer count by 10% from 50 to 45, and our average monthly fee dropped from $10k to $9.28k (and only $7.67k for new contracts). Most importantly, our annual recurring revenue dropped 16.6% from $6 million to $5 million, leaving us 30% short of the Q2 goaleven as expenses exceeded plan by 14%. Based on indications from dissatisfied customers, and continued pricing pressure, we should expect annual recurring revenue to continue dropping to as low as $3.6 million by year end, a 40% decrease for the year. At this rate Acme will inevitably exhaust cash resources within 4 quarters. And so, at the upcoming board meeting, Management will present our recommendation to significantly downsize the operating plan for the remainder of the year. This should give us time to refresh our product strategy, upgrade our sales team, and craft a more scalable network before we have to raise capital.

This example of the contrast between different metrics is hardly extraordinarytechnical problems, competitive pressure, personnel issues, disloyal distributors, economic downturns, and other surprises frequently contribute to churn, price erosion and poor sales productivity. In any given quarter, some indicators are likely to come in ahead of plan, and some behind. Unfortunately, very few companies know how to cull higher-level information from the mixed signals. Even when board members spend hours of the board meeting fishing for details behind the highly vague bookings number, they fail to reach a consensus around the simple question of whether or not it was a good quarter!

Bessemer Venture Partners

Confidential

In addition, without a clear sense of what drives shareholder value, TSVs often run in circles crafting complex compensation plans that encourage renewals, new account generation, usage audits, longer contracts, faster cash collection, upsells, and higher pricesoften at the same time. Each bonus program has an understandable objective, but the resulting hodge podge fails to align incentives correctly. And sales forces, of course, optimize their commissions, not company value.

******************** Crafting the Right Metric What TSVs need is a simple metric that reflects the state of the business as comprehensively as possible as the bookings number does for high-tech product companies. Decisions can then be made based on what optimizes that metric within available resources. Recurring revenue (RR) is the flywheel in the engine that drives value in a TSV. So the primary metric of value must derive somehow from RR. New accounts, higher pricing, lower churn and upsells all contribute to RR, so they simply become components of the primary metric. Theoretically, it could work to track annual RR, but practically speaking it works better to track monthly recurring revenue (MRR), since the number changes dramatically each month. Also, expressing RR in monthly increments facilitates cash management, since monthly expense rates are highly volatile throughout the year. The MRR metric would have greatly simplified the Acme example. A single report would reflect exactly what happened during the quarter without any confusion as to the relative impact of each line item

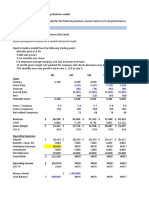

MRR At end of Q1 New Accounts $500,000 $7,000 $8,000 $8,000 ($20,000) ($20,000) ($10,000) ($10,000) ($10,000) ($10,000) ($10,000) ($10,000) ($2,000) ($2,000) ($2,000) ($2,000) ($2,000) ($2,000) ($2,000) $2,833 $2,833 $2,833 $417,500 45 Customers 50 1 AAA 1 BBB 1 CCC -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 DDD EEE FFF GGG HHH III JJJ KKK LLL MMM NNN OOO PPP QQQ RRR PPP QQQ RRR lost to competitor lost to competitor lost to competitor lost to competitor lost to competitor lost to competitor budget constraints budget constraints 20% discount on renewal 20% discount on renewal 20% discount on renewal 20% discount on renewal 20% discount on renewal 20% discount on renewal 20% discount on renewal new service new service new service Account Name Comments

Churn

Upsells

At end of Q2

********************

Bessemer Venture Partners

Confidential

Applying MRR to Sales Compensation Plans Sometimes its easier to sell a new account than to save an old one, and sometimes its not. Some reps know how to close new accounts, some choose to farm their accounts for upsell, while others simply manage to renew all their existing customers and even train them to expand usage. Rather than try to micromanage decisions that are better delegated to the field rep, the TSV can compensate each rep based simply on net change to MRR for his or her territory. Leave it up to the rep to figure out, based on opportunity and skill sets, how to raise MRR by 10%. So long as it happens, its relatively irrelevant as to whether it came principally from upsells, usage expansion, new accounts, or lack of churn. Minor adjustments can still be made to the commission plan to accommodate second order objectives. Reps might earn a small bonus for faster cash payment schedules, and some very minor bonus for one time revenue. But the reps top 3 priorities should be (i) MRR, (ii) MRR, and (iii) MRR.

******************** Committed Monthly Recurring Revenue The objective of a business valuation metric is to tune out the noise and effectively answer the question: if we were to turn off our sales force today, and manage to keep all our existing customers at a steady state, what is our long term revenue outlook? How has that changed in the last month/quarter/year? In the spirit of crafting the perfect answer, our MRR metric still needs a tweak For consumer businesses like Lifelock, a technology service can be provisioned immediately, but for enterprise customers, technology can be hard to deploy whether its delivered as a product or a service. From the time that an enterprise customer signs up with a TSV, there can be a considerable delay before any revenue is recognized at all, while the TSV and customer configure their respective systems to establish a working connection. But since the deployment phase is the least risky stage of the sales cycle, it would be misleading to ignore purchase orders simply because they do not formally count as revenue accounts. Conversely, if a revenue generating account is likely to churn, it would be misleading to represent that customer as a recurring revenue account. So a more meaningful metric for enterprise-oriented TSVs would be Committed Monthly Recurring Revenue (CMRR). To be precise, CMRR equals all recurring revenue in the month, plus purchase orders for future recurring revenue, minus revenue that is likely to churn within the year. The Acme example glossed over the implementation delay, but in reality 2 of the 3 new accounts were purchase ordersnot yet revenue generators at end of Q2. Still, we want to factor those into our valuation as though they were already revenue accounts. Conversely, Acmes network outages had led to some dissatisfaction among other customers who specifically expressed lack of intent to renew in later quarters. A CMRR report would account for those future defections, to capture more accurately changes in company value. (In the happy event that TSVs can later salvage accounts that had already been placed in the category of expected churn, those accounts should be added back to CMRR, reflecting the reality that the companys long term recurring revenue business has risen.)

Bessemer Venture Partners

Confidential

CMRR At end of Q1 New Accounts $500,000 $7,000 $8,000 $8,000 ($20,000) ($20,000) ($10,000) ($10,000) ($10,000) ($10,000) ($10,000) ($10,000) ($2,000) ($2,000) ($2,000) ($2,000) ($2,000) ($2,000) ($2,000) ($10,000) ($10,000) ($10,000) $2,833 $2,833 $2,833 $387,500

Customers 50

Account Name 1 AAA 1 BBB 1 CCC -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 DDD EEE FFF GGG HHH III JJJ KKK LLL MMM NNN OOO PPP QQQ RRR

In Deployment In Deployment lost to competitor lost to competitor lost to competitor lost to competitor lost to competitor lost to competitor budget constraints budget constraints 20% discount on renewal 20% discount on renewal 20% discount on renewal 20% discount on renewal 20% discount on renewal 20% discount on renewal 20% discount on renewal Received written notification Does not return calls Ongoing technical issues new service new service new service

Churn

Expected Churn

-1 SSS -1 TTT -1 UUU PPP QQQ RRR 42

Upsells

At end of Q2

In this case, the CMRR report is even more grave, as it accurately incorporates the negative developments associated with future churn. In most cases, though, CMRR is more favorable than MRR, since deployment delays are more common than churn. Of course, CMRR includes the potentially subjective element of expected churn so it is imperative to establish clear guidelines as to what constitutes a bona fide purchase order, and what qualifies as expected churn. A sharp financial controller will maintain discipline around the guidelines, and certainly gamesmanship on anyones part will be exposed within a couple of quarters as surprise churn appears. With consistent application, CMRR becomes the metric of choice for assessing a CEOs performance in an enterprise-oriented TSV. A recommended practice is to allocate 2/3 of a CEOs bonus on the ending CMRR, and a third of the bonus on ending cash. The cash-based bonus ensure prudent decisions on the way to building market share, especially given how much investment capital it takes for a TSV to break even. Compensating the Sales Force Even when CMRR makes sense for evaluating corporate performance and value, MRR is still the better metric on which to base sales commissions. This motivates the sales rep to shepherd a new account through the deployment phase. Furthermore, if a sales rep were compensated on CMRR, he or she would feel penalized for highlighting accounts at risk for churn, which would lead to greater churn than necessary. While it may make sense to offer very slight adjustments for favorable payment terms and one time revenue, net additions to MRR should dominate the sales reps thoughts.

Bessemer Venture Partners

Confidential

As a TSV matures, it does not want to bog down its top performing sales reps with the job of renewing their growing account bases. So invariably the team splits into hunters for new accounts and farmers for renewals and upsells. Obviously, hunting takes more effort and resource than farming--the Vice-President Sales needs to determine the ratio between the two based on how easy it is to renew an account, and apply that ratio in the sales commissions. For example, $1 of MRR might generate $1 of commission for the first year, and 20 cents for each year of renewal. In this example, the new account sales rep can be compensated for longer term contracts by paying the hunt commission for year one and farm commissions for subsequent years (e.g. $1.40 for a three year contract). In this way, the rep will apply the proper attention to closing long term contracts where the risk of churn has been mitigated.

********************

CMRR as an Investment Tool The Acme example illustrates the hazard of the bookings metric particularly well because the wrong metric is most dangerous when the business is in distress. In healthier quarters, when the business is growing, CMRR still paints a much clearer picture that enables better decisions with respect to employee assessment, compensation, operational planning, and financing. For investors, CMRR is a critical lens that clarifies valuation. Without the CMRR metric, a TSV typically portrays its financial progress over several periods in the following format, borrowed from an actual venture capital investment presentation of a company referred to here as Foobar Services:

EXPENSES BOOKINGS

Foobar delights in showing bookings that now exceed expenses, even though the bookings number, like Acmes, probably includes multi-year bookings, non-renewable revenue, and renewals with no offset for churn. As Acme demonstrated, the bookings number is about as meaningful as division by zero, horoscopes and election promises. Fortunately, Foobars CFO had prepared a slide with GAAP revenue as a footnote for those nerdy auditors

Bessemer Venture Partners

Confidential

EXPENSES BOOKINGS

REVENUE

Typical for a TSV, Foobar grows its revenues every quarter, even when sales activity slows (e.g. even Acmes miserable Q2 showed increasing revenue). Foobar has a large fixed expense nut to cover, but indeed seems headed toward profitability, at which point the value of the business will quickly rise. For a venture investor, this could be the right time to invest, but more detail was needed. Ignoring the one-time revenues, one can see even more smoothness in the growth of Foobars RR.

EXPENSES

REVENUE

RECURRING REVENUE

Allowing for contracted but as-of-yet unrecognized subscriptions, and eliminating the one account expected to churn, shows a CMRR number that outpaces MRR, due to long deployment cycles.

Bessemer Venture Partners

Confidential

10

EXPENSES

CMRR

REVENUE

RECURRING REVENUE

Though CMRR hasnt yet exceeded expenses, the trend line looks strong and, by the way, smoother than the so-called bookings line. The CMRR line not only provides clarity, but also reflects better on the company. In fact, a breakdown of CMRR over the prior 7 periods clearly shows that most of the growth is organic, a terrific indicator of traction and sales leverage

CMRR

New Accounts Upsell & Expansion Renewals

Existing Contracts

This CMRR breakdown graph crisply communicates all the highlights of the business, including new accounts (green), organic growth (purple), renewals (blue), and account cancellations (red arrows). While there is some moderate degree of failure to renew, this TSV actually experiences negative churn, because upsells and service expansion more than offset the cancellations and reductions.

********************

Try It, You will Like It Any new accounting protocol is likely to elicit resistance. Butlike hybrid cars, children-rearing and TivoCMRR is difficult to appreciate until it is experienced. TSVs who have tried reporting CMRR have all embraced it as their primary metric. The CMRR breakdown graph dramatically speeds up meetings, and, when applied to an individual sales territory, shines a clear, bright light on whats working. Except when required externally to report GAAP numbers, these companies now describe all internal results down to individual wins and lossesin terms of CMRR.

Bessemer Venture Partners

Confidential

11

Of course, as markets inevitably mature and slow, the TSVs with dominant market share must shift their businesses to a different metric: Committed Monthly Recurring Contribution (CMRC)! For good reason, many tout the technology-as-a-service business model as one of the greatest dividends of the internet. But without adequate and meaningful measurement tools, TSVs will fade away with so many other dot-com fads.

********************

Bessemer Venture Partners

Confidential

12

You might also like

- Sales Performance Management SaaS A Complete Guide - 2021 EditionFrom EverandSales Performance Management SaaS A Complete Guide - 2021 EditionNo ratings yet

- BCG The One Ratio Every Subscription Business Feb 2017-NL - tcm9-159788Document5 pagesBCG The One Ratio Every Subscription Business Feb 2017-NL - tcm9-159788Monica Ahuja100% (1)

- Bessemer's Top 10 Laws For Being SaaS-yDocument11 pagesBessemer's Top 10 Laws For Being SaaS-yjon.byrum9105100% (4)

- The Ultimate Guide to Calculating Customer Lifetime Value (LTVDocument4 pagesThe Ultimate Guide to Calculating Customer Lifetime Value (LTVkaajitkumarNo ratings yet

- Insights From Endeavor Strategies: What Drives Saas ValuationsDocument8 pagesInsights From Endeavor Strategies: What Drives Saas Valuationsgaurav004usNo ratings yet

- Early-Stage SaaS - Financial ModelDocument22 pagesEarly-Stage SaaS - Financial ModelMau MonroyNo ratings yet

- Perpetual License vs. SaaS Revenue ModelDocument1 pagePerpetual License vs. SaaS Revenue ModelDeb SahooNo ratings yet

- SaasplanecomodelDocument2 pagesSaasplanecomodelapi-336055432No ratings yet

- Mphasis: Performance HighlightsDocument13 pagesMphasis: Performance HighlightsAngel BrokingNo ratings yet

- AA - REPORT Expansion SaaS Benchmarking StudyDocument43 pagesAA - REPORT Expansion SaaS Benchmarking StudyRobert KoverNo ratings yet

- SaaSFinancialPlan2 0Document43 pagesSaaSFinancialPlan2 0Yan BaglieriNo ratings yet

- SaaS ENv2Document27 pagesSaaS ENv2Gopu NairNo ratings yet

- Financial Aspects of Cloud Computing Business ModelsDocument103 pagesFinancial Aspects of Cloud Computing Business ModelsLong LeNo ratings yet

- B2B SaaS Customer Insights Journey MapDocument1 pageB2B SaaS Customer Insights Journey MapBrad B McCormickNo ratings yet

- In Thousands of USD: Lightspeed ForecastDocument15 pagesIn Thousands of USD: Lightspeed ForecastAmy TruongNo ratings yet

- At Time Company Is Formed: Capitalization TableDocument2 pagesAt Time Company Is Formed: Capitalization TableArushi BhandariNo ratings yet

- The Ultimate Cohort Analysis Cheat SheetDocument2 pagesThe Ultimate Cohort Analysis Cheat SheetEduardo MazzucoNo ratings yet

- Kruze Fin Model v8 11 SharedDocument69 pagesKruze Fin Model v8 11 SharedsergexNo ratings yet

- Okta Economic Impact 3.6Document22 pagesOkta Economic Impact 3.6mathurashwaniNo ratings yet

- SaaS Metrics v1.4Document31 pagesSaaS Metrics v1.4Ryan YoungrenNo ratings yet

- Solution Offerings For Retail Industry RCTG ReportDocument11 pagesSolution Offerings For Retail Industry RCTG ReportSurendra Kumar NNo ratings yet

- Collaboration Live User Manual - 453562037721a - en - US PDFDocument32 pagesCollaboration Live User Manual - 453562037721a - en - US PDFIvan CvasniucNo ratings yet

- MM Sales 2 10Document7 pagesMM Sales 2 10Adam MosesNo ratings yet

- Capital Budgeting: FIN 502: Managerial FinanceDocument35 pagesCapital Budgeting: FIN 502: Managerial Financekazimshahgee100% (5)

- Northwestern Mutual v2Document9 pagesNorthwestern Mutual v2Shekhar PawarNo ratings yet

- Financial Aspects of Cloud Computing Business ModelsDocument103 pagesFinancial Aspects of Cloud Computing Business ModelsNaman VermaNo ratings yet

- Equity Vs EVDocument9 pagesEquity Vs EVSudipta ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Saas Metrics 2.0: For Companies That Book Primarily Monthly ContractsDocument16 pagesSaas Metrics 2.0: For Companies That Book Primarily Monthly ContractsOng Peng ChwanNo ratings yet

- SaaS Financial Model Template by ChargebeeDocument15 pagesSaaS Financial Model Template by ChargebeeNikunj Borad0% (1)

- CB Insights Report The Generative AI Market MapDocument24 pagesCB Insights Report The Generative AI Market MapSazones Perú Gerardo SalazarNo ratings yet

- Enablement ROI Calculator For Sales EnablementDocument54 pagesEnablement ROI Calculator For Sales EnablementMartin BossNo ratings yet

- Kruze SaaS Fin Model v1Document66 pagesKruze SaaS Fin Model v1IskNo ratings yet

- Investment Project Financial AnalysisDocument31 pagesInvestment Project Financial AnalysisBinus JoseNo ratings yet

- Colgate-Financial-Model-Solved-Wallstreetmojo ComDocument34 pagesColgate-Financial-Model-Solved-Wallstreetmojo Comapi-300740104No ratings yet

- About ZinnovDocument12 pagesAbout Zinnoviisc cpdmNo ratings yet

- Boast - Ai One PagerDocument5 pagesBoast - Ai One PagerRuss ArmstrongNo ratings yet

- Price Execution How To Get Pricing Power Into Your Sales ForceDocument4 pagesPrice Execution How To Get Pricing Power Into Your Sales ForceasaadNo ratings yet

- SaaS GlossaryDocument2 pagesSaaS GlossaryaaNo ratings yet

- 2Point2 Capital Q2 Investor Update Highlights Tax ImpactDocument5 pages2Point2 Capital Q2 Investor Update Highlights Tax ImpactfbdhaNo ratings yet

- 1/29/2010 2009 360 Apple Inc. 2010 $1,000 $192.06 1000 30% 900,678Document18 pages1/29/2010 2009 360 Apple Inc. 2010 $1,000 $192.06 1000 30% 900,678X.r. GeNo ratings yet

- Top 10 Laws For Being SaaS-y' PDFDocument6 pagesTop 10 Laws For Being SaaS-y' PDFAnonymous OtBVUDNo ratings yet

- Fs Data and AnalyticsDocument5 pagesFs Data and Analyticsvcpc2008No ratings yet

- WSO Free Financial Model Templates GuideDocument14 pagesWSO Free Financial Model Templates GuidekumarmayurNo ratings yet

- Retained Customer Rates Over TimeDocument13 pagesRetained Customer Rates Over TimeDiego SinayNo ratings yet

- M4 - Saas Pricing ModelsDocument11 pagesM4 - Saas Pricing ModelsYash MittalNo ratings yet

- Finance Case Study For Tech Startup Video.01Document10 pagesFinance Case Study For Tech Startup Video.01koenigNo ratings yet

- Scaling Teams: Across Series A To CDocument23 pagesScaling Teams: Across Series A To CKnight CapitalNo ratings yet

- 2018 Work-Bench Enterprise Almanac PDFDocument121 pages2018 Work-Bench Enterprise Almanac PDFkelley henryNo ratings yet

- Customer Acquisition Cost - David SkokDocument1 pageCustomer Acquisition Cost - David Skokapi-204718852No ratings yet

- The Ultimate Guide to Calculating Customer Lifetime Value (LTVDocument2 pagesThe Ultimate Guide to Calculating Customer Lifetime Value (LTVSangram PatilNo ratings yet

- The State of Revenue Operations 2019Document24 pagesThe State of Revenue Operations 2019Kanon Kanon100% (1)

- Marketing PlanDocument17 pagesMarketing PlanSteve WeberNo ratings yet

- Six Value-Adds To Service Chain SuccessDocument4 pagesSix Value-Adds To Service Chain SuccessadillawaNo ratings yet

- A New Approach To Software As Service CloudDocument4 pagesA New Approach To Software As Service CloudGurudatt KulkarniNo ratings yet

- A91 Partners JDDocument2 pagesA91 Partners JDJohn DoeNo ratings yet

- The Future of Telecom OperatorsDocument28 pagesThe Future of Telecom Operatorsjclanger100% (1)

- Deferred RevenueDocument273 pagesDeferred RevenuechetanNo ratings yet

- 50 AAPL Buyside PitchbookDocument22 pages50 AAPL Buyside PitchbookkamranNo ratings yet

- Cloud Vs On Premise SoftwareDocument9 pagesCloud Vs On Premise SoftwareQuang LiemNo ratings yet

- PushingfromMobiletoCloudEnterprise Applications FinalDocument12 pagesPushingfromMobiletoCloudEnterprise Applications Finalanirban_surNo ratings yet

- BI 14 TrendsDocument46 pagesBI 14 TrendsThiran VinharNo ratings yet

- BirlaSoft Oracle MDM Practice 2020Document41 pagesBirlaSoft Oracle MDM Practice 2020Jairo Iván Sánchez100% (1)

- Journey 2 Cloud - EbookDocument52 pagesJourney 2 Cloud - EbookThakkali KuttuNo ratings yet

- Summary Information System ManagementDocument67 pagesSummary Information System ManagementAshagre MekuriaNo ratings yet

- What Is Cloud Computing?: Simple Introduction To Cloud Com PutingDocument32 pagesWhat Is Cloud Computing?: Simple Introduction To Cloud Com PutingNishant SharmaNo ratings yet

- Gartner Reprint 2023Document32 pagesGartner Reprint 2023j9v8v8bw5jNo ratings yet

- Isca MCQ V1.1Document16 pagesIsca MCQ V1.1kumarNo ratings yet

- IRS Social Media Vendor Supplied Research RFI - FinalDocument10 pagesIRS Social Media Vendor Supplied Research RFI - FinalJustin RohrlichNo ratings yet

- Q3 FY23 TranscriptDocument17 pagesQ3 FY23 TranscriptDennis AngNo ratings yet

- Banking Efficiency Beyond Cost CuttingDocument5 pagesBanking Efficiency Beyond Cost CuttingPranoti DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- How To Build A Cloud 720787 NDXDocument12 pagesHow To Build A Cloud 720787 NDXDan BaNo ratings yet

- Disaster Recovery in Cloud Computing SystemsDocument9 pagesDisaster Recovery in Cloud Computing SystemsAdeyeye adewumiNo ratings yet

- Embedded Platform As A Service (ePaaS)Document3 pagesEmbedded Platform As A Service (ePaaS)Sourav KumarNo ratings yet

- Snowflake Core Certification Guide Dec 2022Document204 pagesSnowflake Core Certification Guide Dec 2022LalitNo ratings yet

- Cloud Computing Is Internet-BasedDocument16 pagesCloud Computing Is Internet-BasedsnaveenrajaNo ratings yet

- Product-Led Growth Pricing and Monetizing Your SaaS Business GloballyDocument26 pagesProduct-Led Growth Pricing and Monetizing Your SaaS Business Globallyjai kishanNo ratings yet

- Project Report: Submitted To Prof. Gayathri SampathDocument28 pagesProject Report: Submitted To Prof. Gayathri SampathMithull SinghNo ratings yet

- Remote Backup As A Service Solutions BriefDocument6 pagesRemote Backup As A Service Solutions BriefMario LuizNo ratings yet

- Saas Key PatterenDocument9 pagesSaas Key PatterenBELLA EVENo ratings yet

- Production and Sandbox Environments DifferencesDocument59 pagesProduction and Sandbox Environments DifferencesMalladi Harsha Vardhan Showri100% (1)

- Citrix XenApp Overview BrochureDocument4 pagesCitrix XenApp Overview BrochureAmit ChaubalNo ratings yet

- Answer of Mock Test PaperDocument10 pagesAnswer of Mock Test Paperitr coustomerNo ratings yet

- Cocco PHD ThesisDocument136 pagesCocco PHD ThesisMubashir SheheryarNo ratings yet

- Comparing Cluster, Grid and Cloud Computing ModelsDocument12 pagesComparing Cluster, Grid and Cloud Computing ModelsRosario Rimarachin ReyesNo ratings yet

- HCM - Product Update Oracle Cloud HCM - Human ResourcesDocument34 pagesHCM - Product Update Oracle Cloud HCM - Human ResourcesBarış ErgünNo ratings yet

- System Administration and IT Infrastructure Services 05Document15 pagesSystem Administration and IT Infrastructure Services 05Emey HabulinNo ratings yet

- Birst Appliance v5.21 Quick Start Guide PDFDocument22 pagesBirst Appliance v5.21 Quick Start Guide PDFmanav.gravity2209No ratings yet

- 12 - Cloud Computing Basics PDFDocument5 pages12 - Cloud Computing Basics PDFpooja0100No ratings yet